Plant It Forward Farmers Enrich Houston's Food Scene

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prioritising Support for Locally Controlled Forest Enterprises

Prioritising support for locally controlled forest enterprises Duncan Macqueen (ed.), Emmanuelle Andaya, Samuêl Begaa, Mario Bringas, Martin Greijmans, Tony Hill, Shoana Humphries, Barthelemy Kabore, Thibault Ledecq, Tabin Lissendja, Alphonse Maindo, Amalia Maling, David McGrath, Simon Milledge, Femy Pinto, Nguyen Quang Tan, Elvis Tangem, Stella Schons and Bhishma Subedi Prioritising support for locally controlled forest enterprises Duncan Macqueen (ed.), Emmanuelle Andaya, Samuêl Begaa, Mario Bringas, Martin Greijmans, Tony Hill, Shoana Humphries, Barthelemy Kabore, Thibault Ledecq, Tabin Lissendja, Alphonse Maindo, Amalia Maling, David McGrath, Simon Milledge, Femy Pinto, Nguyen Quang Tan, Elvis Tangem, Stella Schons and Bhishma Subedi First published by the International Institute for Environment and Development in 2014 Copyright © International Institute for Environment and Development All rights reserved For a full list of publications please contact: International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) 80-86 Gray’s Inn Road, London WC1X 8NH Tel: +44 (0)20 3463 7399 Fax: +44 (0)20 3514 9055 pubs.iied.org Citation: Macqueen, D. (ed.), Andaya, E., Begaa, S., Bringa, M., Greijmans, M., Hill, T., Humphries, S., Kabore, B., Ledecq, T., Lissendja, T., Maindo, A., Maling, A., McGrath, D., Milledge, S., Pinto, F., Quang Tan, N., Tangem, E., Schons, S. and Subedi, B. 2014. Prioritising support for locally controlled forest enterprises. IIED, London. This research was funded by UK aid from the Department for International Development. Its conclusions do not necessarily reflect the views of the UK Government. Copyediting by: Alastair Sarre, email: [email protected] Cover photo: Community forestry teak nursery, near Bandung, Java, Indonesia. © Duncan Macqueen / IIED Design by: Eileen Higgins, email: [email protected] Printed by Full Spectrum Print Media, UK on 100% recycled paper using vegetable oil based ink. -

Press Release for Immediate Release

Press Release Contact: Sam Cincotta Wolfgang Beach Strategics 240 405-7129 For Immediate Release http://AbleAndWilling.org Able and Willing Launches Annual Mid-Atlantic Fundraising Campaign Locally-based international nonprofit raising funds to build schools in developing countries Frederick, MD (May 1, 2009). Able and Willing International Education Foundation, a non-profit based in Frederick, launches its Annual Fundraising Campaign with the announcement of two don’t-want-to-miss events in the mid Atlantic region. Proceeds will be used to benefit education in developing countries. The campaign kicks off in our own city of Frederick on May 17th with the return of Puma’s Kitchen, a locally acclaimed dining event presented by Able and Willing, and proudly hosted by Way Station. Celebrating its 10th year, this annual Frederick tradition is orchestrated by, and features the authentic Congolese cuisine of Mbuyu “Puma” Wa Mbuyu, founder of AWIEF. The event includes dinner, plenty of time to enjoy the atmosphere and socialize, and an educational presentation by Puma, which provides the guests an opportunity to learn about Able & Willing and personally meet Puma and his staff. This year, Puma’s Kitchen is proud to present “Lake” the multi-faceted DC-metro area band, to be performing throughout the evening. This year, Puma’s Kitchen goes on the road. On May 23rd, Able and Willing will bring Puma’s Kitchen to the Hope Presbyterian Church in Lakewood, NJ where it will be cosponsored by the Kiwanis Club of Jackson and Hope Presbyterian Church. “We’re really looking forward to these events,” said Puma. -

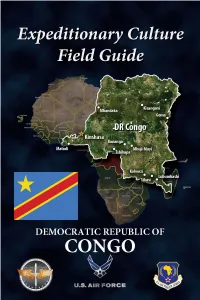

ECFG-DRC-2020R.Pdf

ECFG About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally t complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The he fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success. Democratic Republicof The guide consists of 2 parts: Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment. Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), focusing on unique cultural features of the DRC’s society and is designed to complement other pre-deployment training. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location (Photo courtesy of IRIN © Siegfried Modola). the For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact Congo AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. -

Critical Evaluation of Locally Controlled Forest Enterprise Subsectors Likely To

Critical evaluation of locally 9 controlled forest enterprise subsectors likely to contribute to more integrated, intensive and climate-friendly land use in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Tabin Lissendja, Samuêl Begaa and Alphonse Maindo 9.1 Introduction The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) has 154 million hectares of forest, which is the second-largest area of tropical forest globally after Brazil. Since the post-conflict reform agenda was launched in 2002, pressure on forestland for economic development has grown, both from external sources and from the 70 per cent of DRC’s total population of 60 million people who live in rural areas. Forests are the main source of subsistence for many rural people in DRC. It is estimated that locally controlled forest enterprises in many low- and middle-income countries account for 80-90 per cent of forestry activities in the forest sector (Macqueen, 2008). Locally controlled enterprises generate local wealth, secure community rights to resources, help create social capital through professional associations, encourage greater local environmental responsibility, help preserve cultural identity, and play an important role in poverty reduction. Yet in countries like DRC – and in Kisangani in the east of the country, the focus of this chapter – such SMFEs also face complex problems. Kisangani was selected for the study because growing demand in the local market there has led to an upsurge in artisanal logging. When political activities returned to normal and functional road networks helped revive the local economy after the official end of the war, city-dwellers responded to the lack of state support by starting up numerous income- generating and self-help initiatives. -

2015-2016 Table of Contents

Annual Report 2015-2016 Table of Contents Message from the Acting Director 1 Meet the Staff 4 Faculty reports 8 Pitt Students in Africa 15 Area Schools Experience Africa 23 Student Clubs 26 Let’s Talk Africa 28 African Studies Certif icate Recipients 35 *Cover photo by Dr. Jamie Miller director's Message with great pride particularly at a time when Africa is witnessing momentous transformation with a great sense of optimism and high hopes for a brighter future. As a program we aim to deepen and expand scholarly and educational opportunities not only for our students but for faculty and other stakehold- ers in ways that will enhance learning and understanding of the changing The 2015-2016 academic year perceptions of a continent ever more was yet another exciting year for the integrated in the world. African Studies program (ASP) at the University of Pittsburgh. The pro- This annual report highlights gram experienced tremendous growth several of our significant develop- in student interest in our courses, out ments as well as the achievements of of the classroom learning activities the faculty and students. It provides us and programs abroad in Africa. We with a unique opportunity to share our also saw growing interest among af- progress and reflect together on the filiated faculty and members of the lessons learned from our success and wider Pittsburgh community engaged the challenges ahead as we strive to in Africa related educational and other grow and achieve greater success as a activities. ASP enjoys the support of program. As you will see in the report, over 45 affiliated faculty who support many positive things are happening in the program’s mission through their African Studies and we are having an commitment to serve the students and impact on our students as they prepare active engagement in Africa focused re- for their roles as global leaders and search and scholarship. -

GLOBAL RECIPES Starter Pack

GLOBAL RECIPES starter pack brought to you by: introduction ABOUT Arousing Appetites is a community where ambitious home cooks come The world is a curious place, especially together to discover authentic recipes from around the world. If you’re new to Arousing when it comes to food. Appetites, to help get you Born out of a passion for acquainted with what you can experiencing new cuisines and expect from us, here are a few Because of unique histories, local flavors, all of our recipes are of our most popular recipes traditions and external influences, each rigorously tested and distilled and personal favorites: into methodical, easy-to-follow country's cuisine you’ll see in this steps. If you're willing to get a bit adventurous in the kitchen, you too - Czech Garlic Soup book has developed its own will explore the world through food. - Iraqi Tamarind Fish - Norwegian Almond Wafers highly differentiated style of cooking. Like what you see? And while no cuisine is identical to RECIPES Subscribe to our Arousing another, they all share an Appetites Newsletter and get emphasis on making delicious food that We incessantly research, test and new recipes in your inbox once develop recipes to ultimately offer a week! brings people together to enjoy it in good global comfort food that carefully balances authenticity, simplicity company. and overall healthiness. Each recipe also comes with a little Let’s dive right in! food-history lesson about how each dish came to be. 3. cheesy tortilla street snack Nicaraguan - Quesillo This cheese stuffed tortilla is a staple in Nicaraguan gastronomy and a very popular street snack. -

Fall 2016 VOICES | 25 FALL ADVENTURES

VOICES A Publication from the Language and Culture Center Celebrating FALL 2016 The LCC Team Leadership Team Joy S. Tesh – Director Dr. Jodi Nelms – Associate Director Adam Chen – Program Director of Counseling and Student Services Douglas Jones – Program Manager of Assessment and Technology Jeanne E. Peine – Program Manager of Training and Development Teachers Level 1 Level 4 Kathryn Porter Jenifer Edens Bushra Zaidi Michalina Mrugala Caitlin Sapaugh Level 2 Barbara Kennedy Anna Hood Alida Nakic Level 5 Program Assistants Jana Runnels Level 3 Velva Fallin Greg Urquhart Dale Craven Thong Dang Vincent Tran Susan McAlister Contents Farideh Nekoobahr Level 6 The LCC Team ........................................................... 2 Cory Stewart From the Director’s Desk ....................................... 3 Kitty Barrera LCC Scholarships ..................................................... 4 Saima Khan Counseling and Student Services ......................... 6 Support Staff Healthcare & Admissions Workshop ................... 7 Andrea Goatley – Admissions Manager LCC Student Council ............................................... 8 Jessica Cruz – Office Coordinator Teacher Spotlight: Doug Jones ............................. 9 Thao Le – Financial Coordinator Class Pictures .......................................................... 10 Samrach Long – SEVIS Compliance Coordinator My Country ............................................................. 16 Wa Vuong – Microsystem Analyst LCC Experiences .................................................... -

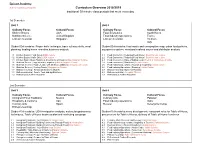

Epicure Academy Overview

Epicure Academy a new culinary program Curriculum Overview 2018/2019 traditional 50 minute class periods that meet every day 1st Semester Unit 1 Unit 2 Culinary Focus Cultural Focus Culinary Focus Cultural Focus Kitchen Basics USA Food Economics South Korea Nutrition Science United Kingdom Food Industry Operations France Entrepreneurship Singapore Entrepreneurship Vietnam Italy Student Deliverables: Proper knife technique, basic culinary skills, meal Student Deliverables: food waste and consumption map, urban food policies, planning, healing home remedies,business analysis aquaponics system, meat and seafood source and distributor analysis 1.1 Kitchen Basics | Food Safety | USA cuisine 2.1 Food Economics | Reducing Food Waste | South Korean cuisine 1.2 Kitchen Basics | Knife Skills | USA cuisine 2.2 Food Economics | Reducing Food Waste | South Korean cuisine 1.3 Kitchen Basic | Meal Planning & Cooking for a Crowd | United Kingdom Cuisine 2.3 Food Economics | Value of Eating Local | French & Vietnamese Cuisine 1.4 Nutrition Science | Ingredient Investigation | United Kingdom Cuisine 2.4 Food Economics | Slow Food | French Cuisine 1.5 Nutrition Science | Food Lifestyle with Medical Conditions | Singaporean Cuisine 2.5 Food Industry Operations | Tourism & Hospitality | Italian Cuisine 1.6 Nutrition Science | Healing Foods | Singaporean Cuisine 2.6 Food Industry Operations | Sourcing | Italian Cuisine 1.7 Entrepreneurship | Restaurant Business Models 2.7 Entrepreneurship | Business Planning 1.8 Entrepreneurship -

Download File

International Journal of Current Advanced Research ISSN: O: 2319-6475, ISSN: P: 2319-6505, Impact Factor: 6.614 Available Online at www.journalijcar.org Volume 9; Issue 03 (D); March 2020; Page No.21670-21676 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.24327/ijcar.2020.21676.4265 Research Article SOCIOECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS OF THE GILO GROUP'S AFRICAN EGGPLANT TRADE (Solanum aethiopicum L.) IN THE MUNICIPAL MARKETS OF BRAZZAVILLE (REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO) Mialoundama Bakouetila Gilles Freddy Rural Economics and Sociology Laboratory, Higher National School of Agronomy and Forestry (ENSAF), Marien Ngouabi University, Congo ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: The objective of this study is to determine the socio-economic characteristics of the african Received 06th December, 2019 eggplant trade in the municipal markets of Brazzaville. The study was carried out in Received in revised form 14th Brazzaville with a sample of 150 traders involved in this trade. The analysis of the survey January, 2020 data was done with the Sphinx Plus software. V.5. The results show that this trade is Accepted 23rd February, 2020 dominated by women of various profiles. It mobilizes young people, adults and constitutes Published online 28th March, 2020 an opportunity for professional integration and women impowerment. The African eggplant sold in Brazzaville comes mainly from rural production areas, and mobilizes Key words: long-type marketing circuits. During the procurement, the actors of this sector maintain several types of relationships based on their social capital. The sale of eggplant is a characteristics, socio-economy, trade, African profitable activity with average gross profit rates on sale of 22%. -

Storing Yearly Little Dues Learning Refugee Diets to Impr

Storing Yearly Little Dues of Wheat, and Wine and Oil: Learning Refugee Diets to Improve Patient Understanding of Nutrition July 2014 Shetal Patel Our refugee patients suffer from significant traumas. restricted financing for household food needs. Eligible Whether the victims of individual brutality or subjects of persons must fall below 130% of the federal poverty a disintegrating state, it is not uncommon for refugees to level. Legal immigrants must have lived in the USA for exhibit significantly harmful psychological behaviors. at least 5 years, or must be receiving disability-related These can be aggravated by the feelings associated with assistance benefits, or must be under the age of 18. The leaving behind one’s family, by attempting to adjust to table at the bottom of the page describes categories of an alien environment, and cultural and linguistic immigrants who may be eligible for SNAP benefits. isolation. SNAP funds may only be used for food items, Foods, particularly familiar and comfortable foods, including breads, cereals, fruits, vegetables, meats, fish, can help ease these feelings. Doctors treating refugee poultry, dairy products, food-producing seeds and plants. populations ought to capitalize on the psychological SNAP restrictions do not prohibit the purchasing of soft boons proper nutritional guidance might yield. By drinks, candy, cookies, or ice cream. The restrictions do couching nutritional guidance in a language familiar to prohibit the purchase of alcohol, tobacco, non- food the refugee patient, doctors may achieve both better items, vitamins, medicines, and hot food. compliance and psychologically curative effects. Because SNAP is administered independently by Below I will identify the nutritional characteristics different states, benefit amounts and eligibility can vary peculiar to some representative refugee populations, from one state to another. -

AFR/RC69/INF/01 19 July 2019 REGIONAL COMMITTEE for AFRICA Sixty-Ninth Session Brazzaville, Republic of Congo, 19–23 August 20

AFR/RC69/INF/01 19 July 2019 REGIONAL COMMITTEE FOR AFRICA ORIGINAL: ENGLISH Sixty-ninth session Brazzaville, Republic of Congo, 19–23 August 2019 INFORMATION BULLETIN TRAVEL AND STAY IN BRAZZAVILLE AFR/RC69/INF/01 Page 2 June 2019 ENTRY VISA An entry visa to the Republic of Congo is mandatory, except for nationals of the Economic Community of Central African States (CEMAC). Visas can be obtained at the Embassy or Consulate of the Republic of Congo in your country of nationality or residence. If there is no diplomatic representation of the Republic of Congo in your country, an authorization of entry into the Republic of Congo must be obtained one week prior to arrival via the WHO Regional Office, by providing a copy of your passport, country of embarkation and flight details. In this case, at the Brazzaville international airport (Maya-Maya) or the autonomous Port (Beach), a visa can be obtained after payment of CFAF 20 000, or €35 or US$ 50. Your passport may be kept by the immigration authorities for processing of the visa and returned 24 hours later. Nationals of CEMAC countries do not require any entry visa; they are only required to have a valid passport. Nationals of Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Mauritania, Morocco, Niger, Senegal and Togo may obtain their visas on arrival. Holders of diplomatic passports and the United Nations Laissez-Passer will be issued a visa on arrival free of charge. Immigration formalities On arrival, you will be met by staff of the Regional Office, who will provide you with the necessary assistance. -

ECFG-DRC-Apr-19.Pdf

ECFG About this Guide This guide is designed to help prepare you for deployment to t culturally complex environments and successfully achieve he mission objectives. The fundamental information it contains will help you understand the decisive cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain necessary skills to achieve mission of Republic Democratic success. The guide consists of 2 parts: Part 1: Introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment. Part 2: Presents “Culture Specific” the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), focusing on unique cultural features of the DRC’s society and is designed to complement other pre- deployment training. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location (Photo courtesy of IRIN © Siegfried Modola). For further information, the visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact Congo AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society.