Stockholm+50 in 2022 – a Challenging Conference with a Forward-Looking Agenda”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

16. Stockholm & Brussels 1911 & 1912: a Feminist

1 16. STOCKHOLM & BRUSSELS 1911 & 1912: A FEMINIST INTERNATIONAL? You must realize that there is not only the struggle for woman Suffrage, but that there is another mighty, stormy struggle going on all over the world, I mean the struggle on and near the labour market. Marie Rutgers-Hoitsema 1911 International Woman Suffrage Alliance (IWSA) became effective because it concentrated on one question only. The Alliance (it will be the short word for the IWSA) wanted to show a combatant and forceful image. It was of importance to have many followers and members. Inside the Alliance, there was no room to discuss other aspect of women's citizenship, only the political. This made it possible for women who did not want to change the prevalent gender division of labor to become supporters. The period saw an increase of the ideology about femininity and maternity, also prevalent in the suffrage movement. But some activists did not stop placing a high value on the question of woman's economic independence, on her economic citizenship. They wanted a more comprehensive emancipation because they believed in overall equality. Some of these feminists took, in Stockholm in 1911, the initiative to a new international woman organization. As IWSA once had been planned at an ICW- congress (in London in 1899) they wanted to try a similar break-out-strategy. IWSA held its sixth international congress in June in the Swedish capital. It gathered 1 200 delegates.1 The organization, founded in opposition to the shallow enthusiasm for suffrage inside the ICW, was once started by radical women who wanted equality with men. -

In Airplane and Ferry Passenger Stories in the Northern Baltic Sea Region

VARSTVOSLOVJE, Risk, Safety and Freedom of Journal of Criminal Justice and Security, year 18 Movement: no. 2 pp. 175‒193 In Airplane and Ferry Passenger Stories in the Northern Baltic Sea Region Sophia Yakhlef, Goran Basic, Malin Åkerström Purpose: The purpose of this study is to map and analyse how travellers at an airport and on ferries experience, interpret and define the risk, safety and freedom of movement in the northern part of the Baltic Sea region with regard to the border agencies. Design/Methods/Approach: This qualitative study is based on empirically gathered material such as field interviews and fieldwork observations on Stockholm’s Arlanda airport in Sweden, and a Tallink Silja Line ferry running between Stockholm and Riga in Latvia. The study’s general starting point was an ethno-methodologically inspired perspective on verbal descriptions along with an interactionist perspective which considers interactions expressed through language and gestures. Apart from this starting point, this study focused on the construction of safety as particularly relevant components of the collected empirical material. Findings: The study findings suggest that many passengers at the airport and on the ferries hold positive views about the idea of the freedom of movement in Europe, but are scared of threats coming from outside Europe. The travellers created and re-created the phenomenon of safety which is maintained in contrast to others, in this case the threats from outside Europe. Originality/Value: The passengers in this study construct safety by distinguishing against the others outside Europe but also through interaction with them. The passengers emphasise that the freedom of movement is personally beneficial because it is easier for EU citizens to travel within Europe but, at the same time, it is regarded as facilitating the entry of potential threats into the European Union. -

Marsyas in the Garden?

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a paper published in Opuscula: Annual of the Swedish Institutes at Athens and Rome. Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Habetzeder, J. (2010) Marsyas in the garden?: Small-scale sculptures referring to the Marsyas in the forum Opuscula: Annual of the Swedish Institutes at Athens and Rome, 3: 163-178 https://doi.org/10.30549/opathrom-03-07 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-274654 MARSYAS IN THE GARDEN? • JULIA HABETZEDER • 163 JULIA HABETZEDER Marsyas in the garden? Small-scale sculptures referring to the Marsyas in the forum Abstract antiquities bought in Rome in the eighteenth century by While studying a small-scale sculpture in the collections of the the Swedish king Gustav III. This collection belongs today Nationalmuseum in Stockholm, I noticed that it belongs to a pre- to the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm. It is currently being viously unrecognized sculpture type. The type depicts a paunchy, thoroughly published and a number of articles on the col- bearded satyr who stands with one arm raised. To my knowledge, four lection have previously appeared in Opuscula Romana and replicas exist. By means of stylistic comparison, they can be dated to 3 the late second to early third centuries AD. Due to their scale and ren- Opuscula. dering they are likely to have been freestanding decorative elements in A second reason why the sculpture type has not previ- Roman villas or gardens. -

Queen Christina's Esoteric Interests As a Background to Her

SUSANNA ÅKERMAN Queen Christina’s Esoteric Interests as a Background to Her Platonic Academies n 1681 the blind quietist, Francois Malaval, stated that Queen Christina of Sweden late in life had ‘given up’ [Hermes] Trismegistos and the IPlatonists, in favour of the Church fathers. The statement does not ex- plain what role the Church fathers were to play in her last years, but it does show that Christina really had been interested in the rather elitist and esoteric doctrine of Hermetic Platonic Christianity. In this paper I shall look at her library to show the depth of this Hermetic involvement. Her interest serves as a background to her life as ex-queen in Italy after her famous abdication from the Swedish throne in 1654, when she was 27 years old. Christina styled herself as the Convert of the Age, and she set up court in Rome where she held a series of scientific and cultural acad- emies in her palace. Her Accademia Reale was staged briefly in the Palazzo Farnese in her first year in Rome, 1656, but was revived in 1674 and was held for a number of years in her own Palazzo Riario.1 Also, Giovanni Ciampini’s Accademia dell’Esperienze, also called Ac cademia Fisico-mathematico, gathered there for their first founding meeting in 1677. Furthermore, she was protectress of the Accademia degli Stravaganti in Collegio Clementina from 1678 and in Orvieto for the Accademia dei Misti. (Christina 1966: 377, cited below as NMU.) Her inspirational presence and resources were valued by many liter- ary figures. After her death in 1689, she was chosen to be a symbolic figurehead, Basilissa (Greek for Empress), by the poets that formed the Accademia dell’Arcadia (D’Onofrio 1976). -

Voluntary Local Review City of Stockholm 2021

Voluntary Local Review City of Stockholm 2021 start.stockholm Voluntary Local Review City of Stockholm 2021 Dnr: KS 2021/156 | Release date: May 2021 | Publisher: Stadsledningskontoret Contact: Elisabet Bremberg, Helen Slätman | Production: BLOMQUIST.SE Opening Statement Opening Statement The year 2020 and 2021 has forced us to radically change our day-to-day lives and our way of living. Things that we used to take for granted, such as spending time with friends, grandchildren and elderly relatives or travelling have been made impossible by the pandemic. In some parts of the world, people’s ability to spend time outside has been limited in an attempt to stop the spread of the covid-19 virus. The pandemic has left deep scars. Lifes has been lost far too soon and loved ones are mourned. Others have become depressed as a result of social isolation or seen their life’s work destroyed due to a faltering economy. We have all been affected in some way. From a socio-economic perspective, many countries have suffered signifcant economic losses as a result of decreased tourism and lockdowns. The fact that we now have several vaccines that can be used to fght covid-19, and that the process of immunising the population has begun, offers hope for the future. We now have the opportunity to build something new, and cities will play an important role in this respect. Vision 2040 Stockholm – City of Opportunities clearly states that the city aims to be a leader when it comes to implementing the 2030 Agenda. Given the effects of the pandemic, it is more important than ever for major cities to continue to work towards achieving the goals relating to economically, socially and environmentally sustainable development. -

Front Matter

ANTICANCER RESEARCH International Journal of Cancer Research and Treatment ISSN: 0250-7005 Volume 35, Number 2, February 2015 Contents Reviews Curcumin and Cancer Stem Cells: Curcumin Ηas Asymmetrical Effects on Cancer and Normal Stem Cells. P.P. SORDILLO, L. HELSON (Quakertown, PA, USA) ....................................................................................... 599 Mechanisms and Clinical Significance of Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors: Epigenetic Glioblastoma Therapy. P. LEE, B. MURPHY, R. MILLER, V. MENON, N.L. BANIK, P. GIGLIO, S.M. LINDHORST, A.K. VARMA, W.A. VANDERGRIFT III, S.J. PATEL, A. DAS (Charleston, SC; Columbus, OH, USA) . 615 Targeting the Peritoneum with Novel Drug Delivery Systems in Peritoneal Carcinomatosis: A Review of the Literature. T.R. VAN OUDHEUSDEN, H. GRULL, P.Y.W. DANKER, I.H.J.T. DE HINGH (Eindhoven, the Netherlands) ............................................................................................................................................................ 627 Mode of Action of Anticancer Peptides (ACPs) from Amphibian Origin. C. OELKRUG, M. HARTKE, A. SCHUBERT (Leipzig, Germany) ........................................................................................................................... 635 Potential Anticancer Properties and Mechanisms of Action of Curcumin. N.G. VALLIANOU, A. EVANGELOPOULOS, N. SCHIZAS, C. KAZAZIS (Athens, Greece; Leicester, UK) ...................................... 645 Experimental Studies In Vitro Evaluation of 3-Arylcoumarin Derivatives in A549 -

Athens, Stockholm and Milan All Feature in The

HOSTELWORLD REVEALS CURRENT TRAVEL WISHLIST Greece is the word: Athens revealed as UK’s most searched for destination since pandemic began • Athens, Stockholm and Milan all feature in the most searched for destinations • Continental travel is the most popular travel choice as Brits opt for European destinations • Staycations are also top of mind as London and Edinburgh feature in the top ten • Italy is the most popular country on the travel wish list, featuring three times in the top ten WEDNESDAY 18TH NOVEMBER, LONDON: Since the pandemic began earlier this year, the ancient metropolis, Athens has been the number one most searched for travel destination1 by British travellers, according to data revealed today by Hostelworld, the global hostel-focussed online booking platform. Drawn by the warm climate, sea views and incredible ruins Athens has to offer, searches for stays in the city increased by 400% from April to October 2020. Other popular metropolitan destinations featured in the most searched for travel locations include: Stockholm, known for fikas and hygge interiors which experienced a 371% increase in searches through Hostelworld; Fashion capital Milan, which saw a 174% increase in searches; and Edinburgh, which came in fourth with a 140% increase. Table 1: Hostelworld’s top ten most searched for destinations (April to October 2020): City Country Percentage increase 1. Athens Greece 400% 2. Stockholm Sweden 371% 3. Milan Italy 174% 4. Edinburgh Scotland 140% 5. London England 71% 6. Berlin Germany 55% 7. Istanbul Turkey 43% 8. Lisbon Portugal 42% 9. Florence Italy 31% 10. Rome Italy 30% The findings suggest travellers are looking to stay closer to home once travel restrictions ease next year, choosing to book short-haul city breaks in Europe rather than long-haul locations. -

Matts Leiderstam

Matts Leiderstam Born 1956 in Gothenburg, Sweden Lives and works in Stockholm, Sweden Matts Leiderstam Panel (57), 2020 Oil and acrylic on poplar panel 29 x 38 cm 11 3/8 x 15 in. Matts Leiderstam Panel (61), 2020 Oil and acrylic on poplar panel 37 x 51 cm 14 5/8 x 20 1/8 in. Matts Leiderstam Panel (55), 2020 Oil and acrylic on poplar panel 37 x 45 cm 14 5/8 x 17 3/4 in. Matts Leiderstam Panel (48), 2020 Oil and acrylic on poplar panel 49 x 69 cm 19 1/4 x 27 1/8 in. Matts Leiderstam Panel (47), 2020 Oil and acrylic on poplar panel 34 x 49 cm 13 3/8 x 19 1/4 in. Matts Leiderstam Panel (60), 2020 Oil and acrylic on poplar panel 37 x 51 cm 14 5/8 x 20 1/8 in. Matts Leiderstam Panel (59), 2020 Oil and acrylic on poplar panel 37 x 51 cm 14 5/8 x 20 1/8 in. Matts Leiderstam Archived (Bloom), 2020 File cover, inkjet print and crayon on "Svenskt Arkiv" A4 paper 37 x 52 cm 14 5/8 x 20 1/2 in. Note: inc. frame Matts Leiderstam Archived (The Edges), 2020 File cover, inkjet print and crayon on "Svenskt Arkiv" A4 paper 37 x 52 cm 14 5/8 x 20 1/2 in. Note: incl. frame Matts Leiderstam Archived (Meetings), 2020 File cover, inkjet print and crayon on "Svenskt Arkiv" A4 paper 37 x 52 cm 14 5/8 x 20 1/2 in. -

Migrant and Refugee Integration in Stockholm

MIGRANT AND REFUGEE INTEGRATION IN STOCKHOLM A SCOPING NOTE [Regional Development Series] Migrant and Refugee Integration in Stockholm A Scoping Note About CFE The OECD Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Regions and Cities provides comparative statistics, analysis and capacity building for local and national actors to work together to unleash the potential of entrepreneurs and small and medium-sized enterprises, promote inclusive and sustainable regions and cities, boost local job creation, and support sound tourism policies. www.oecd.org/cfe/|@OECD_local © OECD 2019 This paper is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and the arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. This document, as well as any statistical data and map included herein, are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. │ 3 Table of contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................................. 5 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................ 7 Foreword ................................................................................................................................................ 8 Key data................................................................................................................................................. -

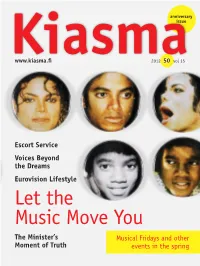

Let the Music Move

anniversary issue www.kiasma.fi 2012 50 vol 15 Escort Service Voices Beyond the Dreams Eurovision Lifestyle Let the Music Move You The Minister’s Musical Fridays and other Moment of Truth events in the spring Cardiff & Miller PORTRAIT BY: BERND BODTLÄNDER / BERND BODTLÄNDER PHOTOGRAPHY / BERND BODTLÄNDER BERND BODTLÄNDER PORTRAIT BY: Janet Cardiff (b. 1957) and George Bures Miller (b. 1960) live in Grindrod, Canada. In 2001 they represented Canada at the Venice Biennale. They were awarded the prestigious German art prize, the Käthe Kollwitz Prize, in 2011. Voices Beyond the Dreams Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller have built their installation The Murder of Crows from voices, songs, music and other sound effects. The viewers find themselves in a space physically and acoustically tuned by 98 loudspeakers and devoid of all potentially narrative visual elements. Kiasma 3 Exhibitions Cardiff & Miller The Murder of Crows (2008) was commissioned by Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary for the Sydney Biennale 2008. ”…it was a very bizarre dream, one of the strangest…” The audience can move among the flocking of speakers, The dark drama of the piece is underlined by its title. lie down on the floor or sit on the wooden folding chairs ‘A murder of crows’ is not only an idiomatic expression for on which some of the black speakers already perch, a grouping of crows, but also an allusion to the violent as if to observe the performance of their colleagues. death with which crows, ravens and other ominous birds All the elements visible in the space are functional and are associated in many traditional stories and myths. -

For the Homeland: Transnational Diasporic Nationalism and the Eurovision Song Contest

FOR THE HOMELAND: TRANSNATIONAL DIASPORIC NATIONALISM AND THE EUROVISION SONG CONTEST SLAVIŠA MIJATOVIĆ A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN GEOGRAPHY YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, CANADA December 2014 © Slaviša Mijatović, 2014 Abstract This project examines the extent to which the Eurovision Song Contest can effectively perpetuate discourses of national identity and belonging for diasporic communities. This is done through a detailed performance analysis of former Yugoslav countries’ participations in the contest, along with in-depth interviews with diasporic people from the former Yugoslavia in Malmö, Sweden. The analysis of national symbolism in the performances shows how national representations can be useful for the promotion of the state in a reputational sense, while engaging a short-term sense of national pride and nationalism for the audiences. More importantly, the interviews with the former Yugoslav diaspora affirm Eurovision’s capacity for the long-term promotion of the ‘idea of Europe’ and European diversities as an asset, in spite of the history of conflict within the Yugoslav communities. This makes the contest especially relevant in a time of rising right-wing ideologies based on nationalism, xenophobia and racism. Key words: diaspora, former Yugoslavia, Eurovision Song Contest, music, nationalism, Sweden, transnationalism ii Acknowledgements Any project is fundamentally a piece of team work and my project has been no different. I would like to thank a number of people and organisations for their faith in me and the support they have given me: William Jenkins, my supervisor. For his guidance and support over the past two years, and pushing me to follow my desired research and never settling for less. -

Madrid Agreement for the Repression of False Or Deceptive Indications of Source on Goods

2632/261(EFS)-0-doc-1 5/23/02 11:28 AM Page 1 Madrid Agreement for the Repression of False or Deceptive Indications of Source on Goods of April 14, 1891 I. Act revised at Washington on June 2, 1911, at The Hague on November 6, 1925, at London on June 2, 1934, and at Lisbon on October 31, 1958 II. Additional Act of Stockhom of July 14, 1967 For more information contact WIPO at www.wipo.int World Intellectual Property Organization 34, chemin des Colombettes P.O. Box 18 CH-1211 Geneva 20 Switzerland Telephone: +41 22 338 91 11 Fax: +41 22 733 54 28 WIPO Publication No. 261(E) ISBN 978-92-805-0270-1 Madrid Agreement for the Repression of False or Deceptive Indications of Source on Goods of April 14, 1891 I. Act revised at Washington on June 2, 1911, at The Hague on November 6, 1925, at London on June 2, 1934, and at Lisbon on October 31, 1958 II. Additional Act of Stockholm of July 14, 1967 {Translation by WIPO) World Intellectual Property Organization GENEVA 1996 WIPOPUBLICATIO!-: No. 261 (E) ISBN 978-92-805-0270-1 WIPO 1967 I Act revised at Washington on June 2, 1911, at The Hague on November 6, 1925, at London on June 2, 1934, and at Lisbon on October 31, 1958 Article 1 (l) All goods bearing a false or deceptive indication by which one of the countries to which this Agreement applies, or a place situated therein, is directly or indirectly indicated as being the country or place of origin shall be seized on importation into any of the said countries.