Hugh Baird College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Course Handbook

Course Handbook Title of the award: BA (Hons) Top up Management in Events Relevant academic year: 2017-18 Name of Course Leader: Samantha Murray Name of host School: School of Management Partner Institution: Hugh Baird College Please read this Handbook in conjunction with the College’s Student Handbook. All course materials, including lecture notes and other additional materials related to your course and provided to you, whether electronically or in hard copy, as part of your study, are the property of (or licensed to) UCLan and MUST not be distributed, sold, published, made available to others or copied other than for your personal study use unless you have gained written permission to do so from the Dean of School. This applies to the materials in their entirety and to any part of the materials. V1 – PCR March 2017 Page 1 of 28 Contents 1 Welcome to the Course 2 Structure of the Course 3 Approaches to teaching and learning 4 Student Support 5 Assessment 6 Classification of Awards 7 Student Feedback 8 Appendices 8.1 Programme Specification(s) V1 – PCR March 2017 Page 2 of 28 1. Welcome to the course Welcome to the course Welcome to your UCLan Higher Education (HE) course at the Hugh Baird University Centre. We offer a friendly and supportive learning environment and the tailored support you need to be successful. Class sizes are small and tutors use varied teaching and learning methods to meet your needs. Our staff are also used to working with people of all ages and recognise that your work and life experience are an asset. -

WORKING with SCHOOLS GUIDE Welcome Page 3

WORKING WITH SCHOOLS GUIDE Welcome page 3 Introduction page 4 Student Support page 5 Our Campuses and Buildings page 6 Activities page 8 South Sefton Campus page 13 Apprenticeships & Traineeships page 14 T-levels page 16 14-16 College page 17 Balliol Road Campus page 18 Thornton College page 21 University Centre page 22 Applications page 24 Key Dates page 25 PAGE 2 Visit www.hughbaird.ac.uk, call Student Services on 0151 353 4444, email [email protected] WELCOME We are very proud at Hugh Baird College of our specialist programme of activities designed to equip young people, teachers and advisers with relevant and up-to-date careers education, information, advice and guidance (CEIAG) on both Further Education and Higher Education opportunities. The activities available aim to support and add value to the information, advice and guidance work being carried out every day in schools and colleges. This publication provides an overview of the wide range of opportunities we offer, including assemblies and presentations (which can be delivered face to face or online), College tours and subject tasters. The guide also contains information about the support we offer at Hugh Baird College as well as highlighting the exciting progression to Higher Education provided by our University Centre. Our work with schools and colleges is designed to assist careers advisors and help students and their key influencers navigate their way through the, sometimes challenging, education landscape. Our activities are delivered at Hugh Baird College, in schools/colleges, or virtually. They are designed to be interactive and enjoyable with lots of opportunities to meet with current students and academic staff. -

Adopting & Embedding Proven Practices & Approaches: Case

Adopting & Embedding Proven Practices & Approaches Case Studies Arising from the National HE STEM Programme ‘Menu of Activities’ Initiative Compiled and Edited by Michael Grove and Les Jones Adopting & Embedding Proven Practices & Approaches Case Studies Arising from the National HE STEM Programme ‘Menu of Activities’ Initiative Compiled and Edited by Michael Grove and Les Jones Copyright Notice These pages contain select synoptic case studies from the National HE STEM Programme ‘Menu of Activities’ Initiative which was launched in two stages in Autumn 2010 and Spring 2011. Their development has been supported by members of the National HE STEM Programme Team and they incorporate final reports, case studies and other information provided by the respective project leads throughout the duration of their projects. The included case studies have been edited by the Editors to ensure a consistent format is adopted and to ensure appropriate submitted information is included. The intellectual property for the material contained within this document remains with the attributed author(s) of each case study or with those who developed the initial series of activities upon which these are based. All images used were supplied by project leads as part of their submitted case studies. Adopting & Embedding Proven Practices & Approaches: Case Studies Arising from the National HE STEM Programme ‘Menu of Activities’ Initiative is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. © The University of Birmingham on behalf of the National HE STEM Programme ISBN 978-0-9567255-6-1 March 2013 Published by University of Birmingham STEM Education Centre on behalf of the National HE STEM Programme University of Birmingham Edgbaston Birmingham, B15 2TT www.hestem.ac.uk Acknowledgments The National HE STEM Programme is grateful to each project lead and author of the case study for their hard work and dedication throughout the duration of their work. -

Framework Users (Clients)

TC622 – NORTH WEST CONSTRUCTION HUB MEDIUM VALUE FRAMEWORK (2019 to 2023) Framework Users (Clients) Prospective Framework users are as follows: Local Authorities - Cheshire - Cheshire East Council - Cheshire West and Chester Council - Halton Borough Council - Warrington Borough Council; Cumbria - Allerdale Borough Council - Copeland Borough Council - Barrow in Furness Borough Council - Carlisle City Council - Cumbria County Council - Eden District Council - South Lakeland District Council; Greater Manchester - Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council - Bury Metropolitan Borough Council - Manchester City Council – Oldham Metropolitan Borough Council - Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council - Salford City Council – Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council - Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council - Trafford Metropolitan Borough - Wigan Metropolitan Borough Council; Lancashire - Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council – Blackpool Borough Council - Burnley Borough Council - Chorley Borough Council - Fylde Borough Council – Hyndburn Borough Council - Lancashire County Council - Lancaster City Council - Pendle Borough Council – Preston City Council - Ribble Valley Borough Council - Rossendale Borough Council - South Ribble Borough Council - West Lancashire Borough Council - Wyre Borough Council; Merseyside - Knowsley Metropolitan Borough Council - Liverpool City Council - Sefton Council - St Helens Metropolitan Borough Council - Wirral Metropolitan Borough Council; Police Authorities - Cumbria Police Authority - Lancashire Police Authority - Merseyside -

North West Introduction the North West Has an Area of Around 14,100 Km2 and a Population of Almost 6.9 Million

North West Introduction The North West has an area of around 14,100 km2 and a population of almost 6.9 million. The metropolitan areas of Greater Manchester and Merseyside are the most significant centres of population; other major urban areas include Liverpool, Blackpool, Blackburn, Preston, Chester and Carlisle. The population density is 490 people per km2, making the North West the most densely populated region outside London. This population is largely concentrated in the southern half of the region; Cumbria in the north has just 24 people per km2. The economy The economic output of the North West is almost £119 billion, which represents 13 per cent of the total UK gross value added (GVA), the third largest of the nine English regions. The region is very varied economically: most of its wealth is created in the heavily populated southern areas. The unemployment rate stood at 7.5 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2010, compared with the UK rate of 7.9 per cent. The North West made the highest contribution to the UK’s manufacturing industry GVA, 13 per cent of the total in 2008. It was responsible for 39 per cent of the UK’s GVA from the manufacture of coke, refined petroleum products and nuclear fuel, and 21 per cent of UK manufacture of chemicals, chemical products and man-made fibres. It is also one of the main contributors to food products, beverages, tobacco and transport equipment manufacture. Gross disposable household income (GDHI) of North West residents was one of the lowest in the country, at £13,800 per head. -

Regional Profiles North-West 29 ● Cumbria Institute of the Arts Carlisle College__▲■✚ University of Northumbria at Newcastle (Carlisle Campus)

North-West Introduction The North-West has an area of around 14,000 km2 and a population of over 6.3 million. The metropolitan area of Greater Manchester is by far the most significant centre of population, with 2.5 million people in the city and its wider conurbation. Other major urban areas are Liverpool, Blackpool, Blackburn, Preston, Chester and Carlisle. The population density is 477 people per km2, making the North-West the most densely populated region outside London. However, the population is largely concentrated in the southern half of the region. Cumbria, by contrast, has the third lowest population density of any English county. Economic development The economic output of the North-West is around £78 billion, which is 10 per cent of the total UK GDP. The region is very varied economically, with most of its wealth created in the heavily populated southern areas. Important manufacturing sectors for employment and wealth creation are chemicals, textiles and vehicle engineering. Unemployment in the region is 5.9 per cent, compared with the UK average of 5.4 per cent. There is considerable divergence in economic prosperity within the region. Cheshire has an above average GDP, while Merseyside ranks as one of the poorest areas in the UK. The total income of higher education institutions in the region is around £1,400 million per year. Higher education provision There are 15 higher education institutions in the North-West: eight universities and seven higher education colleges. An additional 42 further education colleges provide higher education courses. There are almost 177,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) students in higher education in the region. -

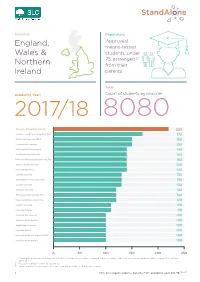

FOI 158-19 Data-Infographic-V2.Indd

Domicile: Population: Approved, England, means-tested Wales & students, under 25, estranged [1] Northern from their Ireland parents Total: Academic Year: Count of students by provider 2017/18 8080 Manchester Metropolitan University 220 Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) 170 De Montfort University (DMU) 150 Leeds Beckett University 150 University Of Wolverhampton 140 Nottingham Trent University 140 University Of Central Lancashire (UCLAN) 140 Sheeld Hallam University 140 University Of Salford 140 Coventry University 130 Northumbria University Newcastle 130 Teesside University 130 Middlesex University 120 Birmingham City University (BCU) 120 University Of East London (UEL) 120 Kingston University 110 University Of Derby 110 University Of Portsmouth 100 University Of Hertfordshire 100 Anglia Ruskin University 100 University Of Kent 100 University Of West Of England (UWE) 100 University Of Westminster 100 0 50 100 150 200 250 1. “Estranged” means the customer has ticked the “You are irreconcilably estranged (have no contact with) from your parents and this will not change” box on their application. 2. Results rounded to nearest 10 customers 3. Where number of customers is less than 20 at any provider this has been shown as * 1 FOI | Estranged students data by HEP, academic year 201718 [158-19] Plymouth University 90 Bangor University 40 University Of Huddersfield 90 Aberystwyth University 40 University Of Hull 90 Aston University 40 University Of Brighton 90 University Of York 40 Staordshire University 80 Bath Spa University 40 Edge Hill -

Members of the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA) 2019-20

Members of the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA) 2019-20 The following institutions are members of QAA for 2019-20. To find out more about QAA membership, visit www.qaa.ac.uk/membership List correct at time of publication – 18 June 2020 Aberystwyth University Activate Learning AECC University College Al-Maktoum College of Higher Education Amity Global Education Limited Anglia Ruskin University Anglo American Educational Services Ltd Arden University Limited Arts University Bournemouth Ashridge Askham Bryan College Assemblies of God Incorporated Aston University Aylesbury College Bangor University Barnsley College Bath College Bath Spa University Bellerbys Educational Services Ltd (Study Group) Bexhill College Birkbeck, University of London Birmingham City University Birmingham Metropolitan College Bishop Grosseteste University Blackburn College Blackpool and The Fylde College Bolton College Bournemouth University BPP University Limited Bradford College Brockenhurst College Buckinghamshire New University Burnley College Burton & South Derbyshire College 1 Bury College Cambridge Regional College Canterbury Christ Church University Cardiff and Vale College Cardiff Metropolitan University Cardiff University CEG UFP Ltd Central Bedfordshire College Cheshire College South and West Chichester College Group Christ the Redeemer College City College Plymouth City of Bristol College City, University of London Colchester Institute Coleg Cambria Cornwall College Coventry University Cranfield University David Game College De Montfort -

2014.06 Access Agreements for 2015-16

August 2017/ 06 Outcomes and data tables This document presents and analyses key data from 2018-19 access agreements Access agreements for 2018-19: key statistics and analysis Alternative formats The publication can be downloaded from the OFFA web-site (www.offa.org.uk/publications). For readers without access to the internet, we can also supply it on CD or in large print. Please call 0117 931 7171 for alternative format versions. Published by the Office for Fair Access. © OFFA 2017 The copyright for this publication is held by the Office for Fair Access (OFFA). The material may be copied or reproduced provided that the source is acknowledged and the material, wholly or in part, is not used for commercial gain. Use of the material for commercial gain requires the prior written permission of OFFA. Erratum: the text of this report was updated in September 2017 to refer to ‘specific learning difficulties’ where previously it had referred to ‘specific learning disabilities’. Access agreements for 2018-19: key statistics and analysis To Heads of higher education institutions in England, Heads of further education colleges in England Of interest to those Implementation of access responsible for agreements, widening participation and fair access, strategic planning, heads of finance, marketing, recruitment and admissions, equality and diversity Reference 2017/06 Publication date August 2017 Enquiries to Tom Lewis-Smith Policy Adviser Email: [email protected] Tel: 0117 931 7171 Summary of key points 1. Approved access agreements for 2018-19, in -

UCU Congress 2021 Attendance List Further Education Delegates

UCU Congress 2021 Attendance List (As of 28 May 2021) Further Education delegates (Congress and sector conference) Roy Bentley Activate Learning Annette Hopwood Hall College Boardman Patricia Roche Anti-Casualisation Committee Vincent Morley Hugh Baird College Julie Rawlinson Bolton College Mel Stouph Hull ACE Elaine White Bradford College Alison Gaughan Kirklees College Alan Hardcastle Bridgwater and Taunton Robin Das Lambeth College College Peter Bicknell Lewisham College - Alison Gander Bunley College Lewisham Way Jayne Gillies Bury College Margot Hill London Regional Committee Mustafa Turus Capital City College Group Vibeke Fussing London South East Colleges Fiona Bailey Capital City College Group (London South (Westminster Kingsway East Colleges) College) Lisa Fortescue- Loughborough College Sharon Broer Central Group (FE) Poole Gursewak Aulakh City College Plymouth Steve Hoggart Middlesbrough College Matthew Bridge City of Bristol College Hayley Sharples Nelson and Colne College Group) Geoff Allan City of Liverpool College Ian Crosson New City College (THC Poplar Rod Chambers Coleg Gwent - Newport Centre) Philip Roy McCabe Coleg Gwent Newport Stuart Drummond New College Durham Alison Greaves Coventry College Stewart Fraser New College, Swindon Yasmin May Croydon College Daniel Baker Newcastle College Neil Stockton Darlington College Railene Barker Nottingham College John Clay Derby College (Wed only) John Reid East Durham College Duncan Harris Nottingham College (Sat & Mon only) Peter Monaghan Eastern & Home Counties Regional Committee -

Annex 3 List of Partners Involved in EU Consultation

Annex 3 List of Partners Involved in EU Consultation Process ORGANISATION 2 Bio Ltd 3tc (Third Sector Technology Centre) ACC Liverpool Acceleris ADAS Age UK Aintree Racecourse Alder Hey AMION Consulting Angel Solutions Arena and Convention Centre Liverpool Arriva North West Atlantic Gateway Baltic Creative base2stay Liverpool LLP Bibby Line Group Ltd Big Issue Invest Big Lottery Fund Bionow BIS Brabners Chaffe Street Britannia Adelphi Hotel Bruntwood Brussels Office Burgundy Gold Butters Innovation Ltd C3 Imaging Cammell Laird Carbon Trust Investment Partners Carillion plc CHamPS Cheshire LEP Chrysalis Clatterbridge Centre for Oncology NHS Trust Community Foundation Merseyside Computer Cab (Liverpool) Ltd Connected Liverpool Connexions CPRE C-Tech Innovation Cumbria Chamber of Commerce Cycle Touring Campaign Dairy Crest Limited Daresbury DCLG Defra DLA Piper UK LLP Downing Property Services Limited Downtown Liverpool DWF E.ON English Heritage Environment Agency ENWORKS European Commisson Federation of Small Businesses First Ark Group Fusion21 Gazeley GETRAG FORD Transmissions GMCP GMLPF Grant Thornton Grosvenor Groundwork Halton & St Helens VCA Halton Chamber of Commerce Halton Council Halton Transport Hartley's Nurseries Highcross Strategic Advisers Limited Hill Dickinson LLP Hit Search Ltd, Liverpool Innovation Park Hope Street Hotel Hugh Baird College In Training Group Independence Initiative Ineos-ChlorVinyls Limited Inner City Solutions Inside Track Media Ltd Instinctive Creations Interconnect IT Inventya Limited IT answers UK Jaguar -

Learning and Teaching Reimagined

Learning and teaching reimagined A new dawn for higher education? November 2020 With thanks to: All those who contributed to this research, from students, staff and leaders to sector organisations and our advisory board. Advisory board members Professor David Maguire, interim principal and vice-chancellor, University of Dundee Chair, learning and teaching reimagined Professor Liz Barnes CBE, vice-chancellor, Staffordshire University Professor Tim Blackman, vice-chancellor, The Open University Professor Nick Braisby, vice-chancellor, Buckinghamshire New University Professor Alec Cameron, vice-chancellor, Aston University Professor Anne Carlisle OBE, vice-chancellor and CEO, Falmouth University Professor Sir Chris Husbands, vice-chancellor, Sheffield Hallam University Professor Tansy Jessop, pro-vice-chancellor, University of Bristol Heidi Fraser-Krauss, executive director of corporate services, The University of Sheffield Professor Julie Lydon, vice-chancellor, University of South Wales Professor Peter Mathieson, principal, The University of Edinburgh Professor Nick Petford, vice-chancellor, University of Northampton Professor Anne Trefethen, pro-vice-chancellor, University of Oxford Ashley Wheaton, principal, University College of Estate Management Advisory board observers Dr Paul Feldman, CEO, Jisc Chris Hale, director of policy, Universities UK Alison Johns, CEO, Advance HE Nic Newman, Emerge Education Authors Professor David Maguire, interim principal and vice-chancellor, University of Dundee Chair, learning and teaching reimagined