1 Supporting LIS Education Through Practice Dr. Loriene Roy Professor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2007–2008 Donor Roster

American Library Association 2007–2008 Donor Roster The American Library Association is a 501(c)(3) charitable and educational organization. ALA advocates funding and policies that support libraries as great democratic institutions, serving people of every age, income level, location, ethnicity, or physical ability, and providing the full range of information resources needed to live, learn, govern, and work. Through the generous support of our members and friends, ALA is able to carry out its work as the leading advocate for the public’s right to a free and open information society. We seek ongoing philanthropic support so that we continue to advocate on behalf of libraries and library users, provide scholarships to students preparing to enter the library profession, promote literacy and community outreach programs, and encourage reading and continuing education in communities across America. Contributions and tax-deductible bequests in any amount are invited. For more information, contact the ALA Development Office at 800.545.2433, or [email protected]. Marilyn Ackerman Jewel Armstrong Player Gary S. Beer Miriam A. Bolotin Heather J. Adair Mary J. Arnold Kathleen Behrendt Nancy M. Bolt Nancy L. Adam Judy Arteaga Penny M. Beile Ruth Bond Martha C. Adamson Joan L. Atkinson Steven J. Bell Lori Bonner Sharon K. Adley Sharilynn A. Aucoin Valerie P. Bell Roberta H. Borman Elizabeth Ahern Sahagian Rita Auerbach Robert J. Belvin Paula Bornstein Rosie L. Albritton Mary Augusta Thomas Betty W. Bender Eileen K. Bosch Linda H. Alexander Rolf S. Augustine Graham M. Benoit Arpita Bose Camila A. Alire Judith M. Auth Phyllis Bentley Laura S. -

Index of /Sites/Default/Al Direct/2008/July

AL Direct, July 2, 2008 Contents U.S. & World News ALA News Booklist Online Division News Awards Seen Online Tech Talk Publishing The e-newsletter of the American Library Association | July 2, 2008 Actions & Answers Calendar U.S. & World News Mesa board cuts librarians “It’s not over. We’re going to continue to do what we can both in Mesa and in Arizona,” Fund Our Future Arizona spokesperson Ann Ewbank told American Libraries June 27, three days after the Mesa Public School board implemented as part of its FY2008–09 budget the replacement over three years of every school library media specialist in the district with library aides. Other Arizona school systems now eyeing the cost of school library programs are the Humboldt Unified School District in Prescott Valley and the Glendale Elementary School District.... Bay County director hired after two-year hiatus After two years without a director, Bay County (Mich.) Library System has appointed Thomas H. Birch Jr. to the position, effective July 21. Birch’s appointment comes some six months after voters approved an For news of ALA Annual operating-millage renewal that was 2/10ths of a mill less than two 1- Conference, see AL mill levies that were defeated in 2006. “We’re feeling very good about Direct’s special post- moving ahead on a whole variety of things,” board Chairman Don conference issue, to be Carlyon told American Libraries.... emailed Monday, July 7. OCLC: National marketing campaign could hike funding From Awareness to Funding: A Study of Library Support in America, a new report issued by OCLC, examines the potential of a national marketing campaign to increase awareness of the value of public libraries and the need for support for libraries at local, state, and national levels. -

SR Ranganathan

AS CINCO LEIS DA BIBLIOTECONOMIA Reproduzido com a gentil permissão do Sr. C. Seshachalam, de Curzon & Co., Madras. Copyright: Curzon & Co. S.R. Ranganathan As Cinco Leis da Biblioteconomia Tradução de Tarcisio Zandonade © Sarada Ranganathan Endowment for Library Science. 1963 Esta tradução: © 2009 by Lemos Informação e Comunicação Ltda. Do original inglês: The five laws of library science (2. ed. 1963) Primeira edição original: 1931 Segunda edição: 1957 Reimpressão (com pequenas correções: 1963) Todos os direitos reservados. De acordo com a lei n° 9610, de 19/2/1998, nenhuma parte deste livro pode ser fotocopiada, gravada, reproduzida ou armazenada num sistema de recuperação de informação ou transmitida sob qualquer forma ou por qualquer meio eletrônico ou mecânico sem o prévio consentimento dos autores e do editor. Este livro obedece ao Acordo Ortográfico da Língua Portuguesa de 1990 Capa: Formatos Design Gráfico Ltda. Revisão e notas: Antonio Agenor Briquet de Lemos e Maria Lucia Vilar de Lemos Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (cip) Cãmara Brasileira do Livro, sp, Brasil Ranganathan, S. R., 1892-1972. As cinco leis da biblioteconomia / S.R. Ranganathan ; tradução de Tarcisio Zandonade. – Brasília, df : Briquet de Lemos / Livros, 2009. Título original: The five laws of library science. Bibliografia. isbn 978-85-85637-38-5 1. Biblioteconomia I. Título. 09-06911 cdd 020 Índices para catálogo sistemático: 1. Biblioteconomia 020 2009 Briquet de Lemos / Livros srts - Quadra 701 - Bloco o - Loja 7 Edifício Centro Multiempresarial Brasília, df 70340-000 Telefones (61) 3322 9806 / 3323 1725 www.briquetdelemos.com.br editora@bríquetdelernos.com.br À Querida Memória de Srimati RUKMINI SUMÁRIO Apresentação desta edição xi Prefácio de sir P.S. -

Spring 2010 Jottingsand DIGRESSIONS

SCHOOL OF LIBRARY & INFORMATION STUDIES Volume 41, No. 2 • Spring 2010 Jottingsand DIGRESSIONS Save the Date JOHN MANIACI/UW HEALTH May 6, 2010 Alumni Association Annual Business Meeting The annual meeting will be held at 1 p.m. in the SLIS conference room. All SLIS alumni are encour- aged to attend. Check the SLIS Web site for an agenda, proposed changes to the SLIS constitution, and the Executive Board ballot. May 13, 2010 Beta Beta Epsilon Meeting and Initiation See article on page 9. May 16, 2010 SLIS Commencement At 9:30 a.m. at Music Hall, followed by a reception at SLIS Library. June 27, 2010 Wisconsin First Lady Jessica Doyle and Dr. Dipesh Navsaria at the grand opening of the Inpatient SLIS Reception at Reading Library at the American Family Children’s Hospital. ALA-Washington, D.C. Join your SLIS colleagues past and present from 5:30 to 7:30 p.m., Share Books Together Sunday, June 27, at Chef Geoff’s Downtown, 13th Street between By Dipesh Navsaria, MD Health’s Department of Pediatrics, E and F streets. We’ll have hors comprise a local implementation of d’oeuvres and a cash bar. All SLIS Share books together. That simple the renowned Reach Out and Read alumni, students and friends are message to parents, heard from many (ROR) program and a unique, innova- welcome. librarians and teachers, now increas- tive Inpatient Reading Library at the ingly will be coming from your doctor. American Family Children’s Hospital October 2010 The Early Literacy Projects, based at (AFCH). As one might expect, SLIS is SLIS Week the UW School of Medicine and Public deeply involved in these ventures. -

American Library Association (ALA) By: American Library Association (ALA)

American Library Association (ALA) By: American Library Association (ALA) The American Library Association (ALA) is the oldest and largest library association in the world, providing association information, news, events, and advocacy resources for members, librarians, and library users. Founded on October 6, 1876 during the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, the mission of ALA is to provide leadership for the development, promotion, and improvement of library and information services and the profession of librarianship in order to enhance learning and ensure access to information for all. Advocacy for Libraries and the Profession: The association actively works to increase public awareness of the crucial value of libraries and librarians, to promote state and national legislation beneficial to libraries and library users, and to supply the resources, training and support networks needed by local advocates seeking to increase support for libraries of all types. Diversity Diversity is a fundamental value of the association and its members, and is reflected in its commitment to recruiting people of color and people with disabilities to the profession and to the promotion and development of library collections and services for all people. Education and Lifelong Learning: The association provides opportunities for the professional development and education of all library staff members and trustees; it promotes continuous, lifelong learning for all people through library and information services of every type. Equitable Access to Information and Library Services The Association advocates funding and policies that support libraries as great democratic institutions, serving people of every age, income level, location, ethnicity, or physical ability, and providing the full range of information resources needed to live, learn, govern, and work. -

ALA Conference Report: E-Book Standards ILA Annual Conference Ted Schwitzner Usage”

ILLINOIS ASSOCIATION OF COLLEGE AND RESEARCH LIBRARIES IACRL NEWSLETTER VOLUME 39, ISSUE 2 F A L L 2 0 1 6 U P C O M I N G EVENTS ALA Conference Report: E-Book Standards ILA Annual Conference Ted Schwitzner Usage”. Albanese reported that Rosemont, IL CARLI respondents, who were public Oct. 18-20, 2016 library patrons, identified that the A broad set of user expectations library was first in their minds ALA Midwinter for e-books occupied the when they began to look for a thoughts of attendees at “The book. While many used e- Conference Changing Standards Landscape: readers, most preferred to use Atlanta, GA The User’s Experience”, the 10th print books, however. Re- Jan. 19-24, 2017 Annual NISO/BISG Forum on sponses correlated with polling June 24 at the ALA Annual Con- of libraries on limited e-book ference in Orlando. (NISO is an borrowing, where two-thirds of ACRL 2017 acronym for National Information libraries attributed e-book lend- Conference Standards Organization, while ing to less than 10% of their Baltimore, MD BISG stands for Book Industry patrons. Among patrons engag- Mar. 22-25, 2017 Study Group.) ing in e-book use, convenience sales of e-books as a whole is the main value sought in se- have tailed off from a peak mar- Andrew Albanese of Publishers lecting an e-book, though 36% of ket share of 24% in the first Weekly led off the Forum with patrons expressed willingness to quarter of 2014. A joint study results and analysis from an be placed on a waiting list for an between BISG and the Nielsen ALA/BISG survey on “Patron e-book. -

ALISE 2013 Official Program

ALISE ’13 Always the Beautiful Question: Inquiry Supporting Teaching, Research, & Professional Practice January 22–25, 2013 • Seattle, Washington Stop by our booth to review these and many more new and bestselling textbooks! ALA Neal-Schuman purchases fund advocacy, awareness and accreditation programs for library professionals worldwide neal-schuman.com WELCOME Message from the President Welcome to the ALISE 2013 conference in Seattle, Also to be celebrated is the hard work and contributions of the many hands Washington. This year’s theme, “Always the that are needed to ensure a stimulating annual conference experience. Beautiful Question: Inquiry Supporting Teaching, My deepest thanks go to Conference Co-Chairs Don Latham and Heidi Research, and Professional Practice,” celebrates the Julien who have been indefatigable in their commitment to the conference desire to know as the heart of teaching and learning, planning. Many thanks also to the entire Conference Planning Committee research and scholarship, technical innovation, and (all of whom are amazing), our hard working ALISE committees, and professional development. The response from the to our vendors and institutional sponsors. I also want to express my ALISE membership has been an array of beautiful appreciation to the ALISE membership for giving me the opportunity to questions in the form of panels, papers, posters, programs, and workshops serve the Association in a second term on the Board, to Lynne Howarth, that promise to spark new beautiful questions and further study. I hope Eileen Abels, and the other members of the ALISE Board of Directors who that you will enjoy engaging with colleagues, making new friends, and have been my counsel and my help over the course of this year. -

United States Symposium and Workshop on Library and Information Science Education in the Digital Age

Proceedings of the 2000 Sino- United States Symposium and Workshop on Library and Information Science Education in the Digital Age November 5-10, 2000 Wuhan, China D. E. Perushek Editor Council on Library and Information Resources Washington, D.C. Proceedings of the 2000 Sino-United States Symposium and Workshop on Library and Information Science Education in the Digital Age November 5-10, 2000 Wuhan, China D. E. Perushek Editor Council on Library and Information Resources Washington, D.C. About the Editor D. E. Perushek, assistant university librarian for collection management at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, studied library science at the University of Michigan and the University of Chicago. She began her library career as head of the Wason Collection at Cornell University. Subsequently, she was curator of the Gest Oriental Library and East Asian Collection at Princeton University, then associate dean for collection services at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. She has worked with Fudan University in Shanghai, China, on a project to microfilm books from the Sino-Japanese War period with support from the Henry Luce Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities. Her current research interests lie in materials budget allocation and collection assessment. ISBN 1-887334-86-6 Published by: Council on Library and Information Resources 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Suite 500 Washington, DC 20036 Web site at http://www.clir.org Copyright 2001 by the Council on Library and Information Resources ii Contents Foreword -

Current ALA Offices Include

EBD #12.14 2016-2017 Report to Council and Executive Board December 6, 2016 Keith Michael Fiels Executive Director Symposium on the Future of Libraries The Symposium on the Future of Libraries, organized by the Center for the Future of Libraries, will provide three days — Saturday, Sunday, and Monday of Midwinter — for exploring the many futures for academic, public, school and special libraries. Plenary sessions will feature Atlanta-based civic, social, and education innovators. The Center received over 50 proposals for concurrent sessions and a schedule of selected sessions is now available. The Symposium on the Future of Libraries is included with 2017 ALA Midwinter Meeting and Exhibits full registration. Library Boot Camp Advocacy Training The Office for Library Advocacy and the Office for Intellectual Freedom have launched Advocacy Bootcamp, a new advocacy training geared for state chapter conferences, focused on mentorship of new advocates, building an advocacy plan for individual libraries and creating consistent messaging for all types of libraries. Two Boot Camps have taken place so far: at the Minnesota Library Association and Virginia Library Association Conferences. As a result of these (with a combined attendance of about 55), 22 participants said they would adopt the Libraries Transform campaign; 20 said they wanted to get involved in their respective Chapter advocacy work; 18 said they wanted to be involved in mentorship; four said they would join ALA and 10 said they wanted to become active in reporting intellectual freedom and advocacy challenges. AASL Presents 30 ESSA State Workshops in 60 Days When presentations wrapped in Nebraska and Alaska on November 11, AASL completed a monumental task of facilitating 30 state-level Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) workshops in only 60 days. -

2013 Program

International Conference of Indigenous Archives, Libraries, and Museums June 10–13 2013 Hyatt Regency Tamaya Spa and Resort Santa Ana Pueblo, New Mexico www.firstpeoplesnewdirections.org U NIVERSITY OF A RIZONA P RESS | U NIVERSITY OF M INNESOTA P RESS U NIVERSITY OF N ORTH C AROLINA P RESS | O REGON S TAT E U NIVERSITY P RESS Decolonizing Museums The Indian School on Representing Native America in National Magnolia Avenue and Tribal Museums Voices and Images from Sherman Institute Amy Lonetree Edited by Clifford E. Trafzer, Museum exhibitions focusing on Matthew Sakiestewa Gilbert, Native history have long been and Lorene Sisquoc curator controlled. However, The first collection of writings Indigenous people are now taking a focused on an off-reservation Indian larger role in determining exhibition boarding school, this book draws upon content. This book explores how documents held at the Sherman Indian museums grapple with centuries of Museum and features the voices of unresolved trauma as they tell the American Indian students. stories of Native peoples. Paper, 6 x 9, $24.95 Paper, 6.125 x 9.25, $24.95 www.osupress.oregonstate.edu www.uncpress.unc.edu OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA PRESS Survival Schools Mark My Words The American Indian Movement and Native Women Mapping Our Nations Community Education in the Twin Cities Mishuana Goeman Julie L. Davis Traces settler colonialism as an Draws together the voices of teachers, enduring form of gendered spatial parents, and students for an in-depth violence, showing how it persists history of the founding of the Ameri- in the current context of neoliberal can Indian Movement, early com- globalization. -

Washington Libraries Washington State Library

Washington State Library 2006 Directory of Washington Libraries Washington State Library 2006 Directory of Washington Libraries For questions regarding information listed in the 2006 Directory of Washington Libraries or to update your library entry at any time, feel free to telephone, email or fax information to either: Jeremy Stroud, Communications Consultant Bobbie DeMiero, Secretary Administrative Washington State Library Washington State Library Office of the Secretary of State Office of the Secretary of State (360) 570-5583 (360) 570-5577 Toll Free 1-866-538-4996 Toll Free 1-866-538-4996 Fax (360) 586-7575 Fax (360) 586-7575 [email protected] [email protected] A database of directory information is available electronically via the Washington State Library homepage: http://ww.secstate.wa.gov/library Please note: The information in this directory is provided to the Washington State Library by local libraries as a reference for the libraries of Washington State. Some libraries may elect not to submit complete information. TABLE OF CONTENTS Academic Libraries ...................................................................................................................1 Government Libraries .............................................................................................................27 Federal Depositories ............................................................................................................28 Washington State Depositories ............................................................................................29 -

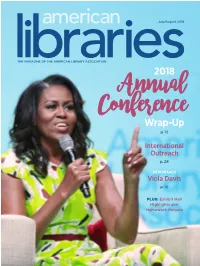

2018 Wrap-Up

July/August 2018 THE MAGAZINE OF THE AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION 2018 Annual Conference Wrap-Up p. 12 International Outreach p. 28 NEWSMAKER Viola Davis p. 10 PLUS: Exhibit Hall Highlights and Homework Helpers REV UP YOUR RESEARCH... … With the ScanPro All-In-One™! With the ScanPro All-In-One, you can have the best of both worlds with the first and only truly universal microfilm solution available. And, it’s affordable! All The Capabilities You Need: • On-demand reader, printer, scanner for all film types • Optional, new AUTO-Scan® Pro software scans 100 images per minute for roll film and fiche • High-speed, desktop conversion scanner for roll film and fiche • Fully upgradeable any time for additional features • Includes the new AUTO-Carrier™ for automatic scanning • Best-in-industry, 3-year factory warranty of roll film and fiche Contact your local reseller for a demo and ask about our current promotion! 340 Grant Street Hartford, WI 53027 • p) 800-251-2261 • www.e-imagedata.com July/August 2018 American Libraries | Volume 49 #7/8 | ISSN 0002-9769 COVER STORY 12 Big Conversations in the Big Easy 2018 Annual Conference Wrap-Up BY Anne Ford FEATURES UP FRONT TRENDS 22 Tech in the Exhibit Hall 2 From the Editor NEWSMAKER 10 Viola Davis Convergence, partnerships, and niche players Back from the Bayou BY Sanhita SinhaRoy Award-winning BY Marshall Breeding actor brings beloved 4 From Our Readers bear Corduroy to a new generation INTERNATIONAL OUTREACH ALA 28 2018 Presidential 11 Noted & Quoted Citation Awards 3 From the President Libraries = Strong EDITED BY Phil Morehart Communities SOLUTIONS BY Loida Garcia-Febo 38 Make It 3D 31 Building Bridges to the East Alternative 3D 6 Update BY Michael Dowling production platforms What’s happening at ALA 32 On the Road Again PEOPLE BY Chase Ollis 40 Announcements 34 Staffing Your THE BOOKEND Homework- 42 Midday Masquerade Help Center 42 Pairing the right minds with student learners BY Cindy Mediavilla ON THE COVER: Michelle Obama.