20170803 POA-2012-0138 SAWC SAMF NOI And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wilderness in Southeastern Alaska: a History

Wilderness in Southeastern Alaska: A History John Sisk Today, Southeastern Alaska (Southeast) is well known remoteness make it wild in the most definitive sense. as a place of great scenic beauty, abundant wildlife and The Tongass encompasses 109 inventoried roadless fisheries, and coastal wilderness. Vast expanses of areas covering 9.6 million acres (3.9 million hectares), wild, generally undeveloped rainforest and productive and Congress has designated 5.8 million acres (2.3 coastal ecosystems are the foundation of the region’s million hectares) of wilderness in the nation’s largest abundance (Fig 1). To many Southeast Alaskans, (16.8 million acre [6.8 million hectare]) national forest wilderness means undisturbed fish and wildlife habitat, (U.S. Forest Service [USFS] 2003). which in turn translates into food, employment, and The Wilderness Act of 1964 provides a legal business. These wilderness values are realized in definition for wilderness. As an indicator of wild subsistence, sport and commercial fisheries, and many character, the act has ensured the preservation of facets of tourism and outdoor recreation. To Americans federal lands displaying wilderness qualities important more broadly, wilderness takes on a less utilitarian to recreation, science, ecosystem integrity, spiritual value and is often described in terms of its aesthetic or values, opportunities for solitude, and wildlife needs. spiritual significance. Section 2(c) of the Wilderness Act captures the essence of wilderness by identifying specific qualities that make it unique. The provisions suggest wilderness is an area or region characterized by the following conditions (USFS 2002): Section 2(c)(1) …generally appears to have been affected primarily by the forces of nature, with the imprint of man’s work substantially unnoticeable; Section 2(c)(2) …has outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation; Section 2(c)(3) …has at least five thousand acres of land or is of sufficient FIG 1. -

2020–2021 Statewide Commercial Fishing Regulations Shrimp, Dungeness Crab and Miscellaneous Shellfish

Alaska Department of Fish and Game 2020–2021 Statewide Commercial Fishing Regulations Shrimp, Dungeness Crab and Miscellaneous Shellfish This booklet contains regulations regarding COMMERCIAL SHELLFISH FISHERIES in the State of Alaska. This booklet covers the period May 2020 through March 2021 or until a new book is available following the Board of Fisheries meetings. Note to Readers: These statutes and administrative regulations were excerpted from the Alaska Statutes (AS), and the Alaska Administrative Code (AAC) based on the official regulations on file with the Lieutenant Governor. There may be errors or omissions that have not been identified and changes that occurred after this printing. This booklet is intended as an informational guide only. To be certain of the current laws, refer to the official statutes and the AAC. Changes to Regulations in this booklet: The regulations appearing in this booklet may be changed by subsequent board action, emergency regulation, or emergency order at any time. Supplementary changes to the regulations in this booklet will be available on the department′s website and at offices of the Department of Fish and Game. For information or questions regarding regulations, requirements to participate in commercial fishing activities, allowable activities, other regulatory clarifications, or questions on this publication please contact the Regulations Program Coordinator at (907) 465-6124 or email [email protected] The Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) administers all programs and activities free from discrimination based on race, color, national origin, age, sex, religion, marital status, pregnancy, parenthood, or disability. The department administers all programs and activities in compliance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, and Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972. -

VIOLENCE, CAPTIVITY, and COLONIALISM on the NORTHWEST COAST, 1774-1846 by IAN S. URREA a THESIS Pres

“OUR PEOPLE SCATTERED:” VIOLENCE, CAPTIVITY, AND COLONIALISM ON THE NORTHWEST COAST, 1774-1846 by IAN S. URREA A THESIS Presented to the University of Oregon History Department and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts September 2019 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Ian S. Urrea Title: “Our People Scattered:” Violence, Captivity, and Colonialism on the Northwest Coast, 1774-1846 This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the History Department by: Jeffrey Ostler Chairperson Ryan Jones Member Brett Rushforth Member and Janet Woodruff-Borden Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2019 ii © 2019 Ian S. Urrea iii THESIS ABSTRACT Ian S. Urrea Master of Arts University of Oregon History Department September 2019 Title: “Our People Scattered:” Violence, Captivity, and Colonialism on the Northwest Coast, 1774-1846” This thesis interrogates the practice, economy, and sociopolitics of slavery and captivity among Indigenous peoples and Euro-American colonizers on the Northwest Coast of North America from 1774-1846. Through the use of secondary and primary source materials, including the private journals of fur traders, oral histories, and anthropological analyses, this project has found that with the advent of the maritime fur trade and its subsequent evolution into a land-based fur trading economy, prolonged interactions between Euro-American agents and Indigenous peoples fundamentally altered the economy and practice of Native slavery on the Northwest Coast. -

White Sulphur Springs Bathhouse Environmental Assessment - Key Acronyms and Other Terms

White Sulphur Springs Bathhouse United States Department of Agriculture Environmental Assessment Forest Service Volume A, Environmental Assessment Tongass National Forest Tongass National Forest R10-MB-713a Ketchikan, Alaska February 2012 [email protected] White Sulphur Springs Bathhouse Environmental Assessment - Key Acronyms and Other Terms Native American Graves ACMP Alaska Coastal Management Plan NAGPRA Protection and Repatriation Act Alaska Department of Fish and National Environmental Policy ADF&G Game NEPA Act American Indian Religious AIRFA Freedom Act NFS National Forest System Alaska Native Claims Settlement National Historic Preservation ANCSA Act NHPA Act Alaska National Interest Lands National Marine Fisheries ANILCA Conservation Act NMFS Service National Oceanic and BMP Best Management Practices NOAA Atmospheric Administration Recreation Opportunity CEQ Council on Environmental Quality ROS Spectrum CFR Code of Federal Regulations SD Service Day State Historic Preservation CZMA Coastal Zone Management Act SHPO Officer DN Decision Notice SOPA Schedule of Proposed Actions EA Environmental Assessment SUA Special Use Authorization ESA Endangered Species Act TE Threatened and Endangered Forest Tongass Land and Resource FONSI Finding of No Significant Impact Plan Management Plan FSH Forest Service Handbook TTRA Tongass Timber Reform Act United States Fish and Wildlife FSM Forest Service Manual USFWS Service IDT Interdisciplinary Team VCU Value Comparison Unit LUD Land Use Designation The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual's income is derived from any public assistance program. -

Gulf of Alaska Sep 2021 U.S

346 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 8, Chapter 15 19 SEP 2021 Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 8—Chapter 15 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage 135°W http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 137°W 136°W CANADA UNITED ST ATES CANADA UNITED STATES 17318 59°N 17316 L Y G N L A N C I E R C B A A Y N A L 17301 CROSS SOUND Hoonah ICY STRAIT C C H H YAKOBI A 58°N I ISLAND C T H H 17302 A A M G O F 17303 S T R A I I S T L A N D GULF OF ALASKA 19 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 8, Chapter 15 ¢ 347 Cross Sound and Icy Strait (1) This chapter describes Cross Sound and Icy Strait, at tidesandcurrents.noaa.gov for specific information which are the northernmost sea connections for the inland about times, directions, and velocities of the current at passages of southeastern Alaska. Also described are the numerous locations throughout the area, including Cross tributary waterways and the various communities in the Sound and Icy Strait. Links to a user guide for this service area, such as Pelican, Elfin Cove, Gustavus and Hoonah. can be found in chapter 1 of this book. (10) Strong tide rips occur at the entrance to Swanson (2) Harbor with a slight S breeze. ENCs - US3AK3AM, US3AK4ZM, US4AK3AM (11) On the south side of Icy Strait between Point Sophia Chart - 17300 and Point Augusta very little current is encountered. -

Reconnaissance Geology of Chichagof, Baranof, and Krui:Of Islands, , Southeastern Alaska

LIBRAR~ Reconnaissance Geology of Chichagof, Baranof, and Krui:of Islands, , Southeastern Alaska GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 792 / RECONNAISSANCE GEOLOGY OF CHICHAGOF, BARANOF, AND KRUZOF ISLANDS, SOUTHEASTERN ALASKA Rugged interior of Baranof Island west of Carbon Lake; note Sitka Sound and Mount Edgecumbe in upper right. Reconnaissance Geology of Chichagof, Baranof, and Kruzof Islands, Southeastern Alaska By ROBERT A. LONEY, DAVID A. BREW, L. J. PATRICK MUFFLER, and JOHN S. POMEROY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 792 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON: 1975 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 74--600121 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Goverri'rrient Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402- Price (paper cover) Stock Number 2401-02560 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract --_------- __ ----------__ ----__ -------------------- 1 Intrusive igneous rocks-Continued Introduction----------------------------------------------· 2 Granitoid rocks-Continued Location ---------------------------------------------- 2 Jurassic plutons-Continued Previous investigations -------------------------------- 2 Kennel Creek pluton -------------------------- 27 Present investigation ---------------------------------- 3 Tonalite intrusives near the west arm of Peril Acknowledgments ------------------------------------ 3 Strait -------------------------------------- 27 GeographY-------------------------------------------- -

Geopolitics and Environment in the Sea Otter Trade

UC Merced UC Merced Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Soft gold and the Pacific frontier: geopolitics and environment in the sea otter trade Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/03g4f31t Author Ravalli, Richard John Publication Date 2009 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California 1 Introduction Covering over one-third of the earth‘s surface, the Pacific Basin is one of the richest natural settings known to man. As the globe‘s largest and deepest body of water, it stretches roughly ten thousand miles north to south from the Bering Straight to the Antarctic Circle. Much of its continental rim from Asia to the Americas is marked by coastal mountains and active volcanoes. The Pacific Basin is home to over twenty-five thousand islands, various oceanic temperatures, and a rich assortment of plants and animals. Its human environment over time has produced an influential civilizations stretching from Southeast Asia to the Pre-Columbian Americas.1 An international agreement currently divides the Pacific at the Diomede Islands in the Bering Strait between Russia to the west and the United States to the east. This territorial demarcation symbolizes a broad array of contests and resolutions that have marked the region‘s modern history. Scholars of Pacific history often emphasize the lure of natural bounty for many of the first non-natives who ventured to Pacific waters. In particular, hunting and trading for fur bearing mammals receives a significant amount of attention, perhaps no species receiving more than the sea otter—originally distributed along the coast from northern Japan, the Kuril Islands and the Kamchatka peninsula, east toward the Aleutian Islands and the Alaskan coastline, and south to Baja California. -

Assessing Possible Cruise Ship Impacts on Huna Tlingit Ethnographic Resources in Glacier Bay

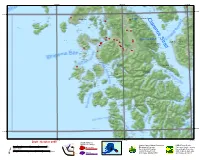

Portland State University PDXScholar Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations Anthropology 2014 Assessing Possible Cruise Ship Impacts on Huna Tlingit Ethnographic Resources in Glacier Bay Douglas Deur Portland State University, [email protected] Thomas Thornton University of Oxford Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/anth_fac Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sustainability Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Deur, Douglas and Thornton, Thomas, "Assessing Possible Cruise Ship Impacts on Huna Tlingit Ethnographic Resources in Glacier Bay" (2014). Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations. 102. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/anth_fac/102 This Report is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. ASSESSING POSSIBLE CRUISE SHIP IMPACTS ON HUNA TLINGIT ETHNOGRAPHIC RESOURCES IN GLACIER BAY FINAL REPORT Douglas Deur, Ph.D. Department of Anthropology Portland State University Thomas F. Thornton, Ph.D. Environmental Change Institute School of Geography and the Environment University of Oxford & Portland State University (Affiliate) With Significant Contributions by Jamie Hebert, M.A. and Rachel Lahoff , M.A. Department of Anthropology, Portland State University 2014 Completed under Cooperative Agreement H8W07060001 between Portland State University and the National Park Service. ANTHROPOLOGY DEPARTMENT - PORTLAND STATE UNIVERSITY P.O. Box 751 / 1721 SW Broadway, Portland, OR 97207 Figure 1: Huna Tlingit participants in the annual NPS-sponsored community boat trip, at the base of Margerie Glacier, with Mount Fairweather visible above. -

Bruce IL J-P Hd. Karl

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP 1-1506 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC MAP OF WESTERN CHCCHAGOF AND YAKOBI ISLANDS, SOUTHEASTERN ALASKA Bruce IL J-P and S- hd. Karl INTRODUCTION and mudstone turbidite and massive graywacke and conglomerate, which constitute the Sitka Gramacke. Western Chichagof and Yakobi Islands are in the Subsequent to the amalgamation of these four belts of Alexander Archipelago of southeastern Alaska. The rocks, the entire study area has been intruded by study area, which is within the Tonga- National ~ertik~(?)plutoas - composed dominantly of Forest, was under consideration for wilderness nonfoliated tonalite, granodiorite, and granite. designation at the time of this study. Public Law 96- 487 (December 2, 1980) created a wilderness area PREVIOUS WORK which includes almost all of the area of this study. The study area ia bounded on the northeast by a linear The earliest interest in the geology of Yakobi topographic low which includes Hoonah Sound and and western Cbichagof Islands resulted from the Lisiamki Inlet, and which nearly separates eastern discovery of gold-be&ing quartz veins near Klag Bay Chichagof Island from western Chichagof Island. The in 1905. C. W. Wright examined the shoreline of area is bounded on the southeast by Peril Strait, on the Chichagof Island and reported the gold discovery in northwest by Cross Sound, and on the southwest by the 1906. He spent the next season visiting claims which Pacific Ocean. The area is approximately 95 he briefly described in 1907 (Wright and Wright, 1906, kilometers long by 32 kilometers wide at the widest p. -

New Cantabria

New Cantabria Alaska 1n the last chron icles of the Spanish Empire by Arsenio Rey-Tejerina to Raul Ornelas. As soon as I saw his family to Anchorage. I was coming Several coincidences contributed to name on the bridge bulletin, I asked to initiate a Department of Foreign make my sea voyage to Alaska a one of the officers to take me to the Languages at the University of memorable one. There I was, another control room. I was deeply moved to A Iaska, Anchorage. Spaniard, navigating the Inside shake his hand and touch the helm. I We embarked in Seattle at the end Passage, marveling at the landscape held it for awhile under his watchful of August. Hanging from my neck I in the wake of my fellow coun eye. There I was, a novice mariner, had a pair of binoculars and in my trymen who had come the same way driving that huge boat through rocky hands a map on which I had jotted over two hundred years earlier. waters with a sea coast dappled with all the Spanish names gathered from On old Spanish maps I have seen, hundreds of little islands backdrop my research on the discoveries of the area was called New Cantabria, ped by the snow covered mountains those intrepid sailors who had come which I thought an appropriate and thundering glaciers, just as my up from San Bias port, just north of name, because of it's striking ancestors had done when they came present day Acapulco. similarities in climate and geography exploring all the nooks and crannies Captain Ornelas was taken aback with the Cantabric region where I of this coast. -

C Larence Strait

Strait Tumakof er Lake n m u S 134°0'0"W 133°0'0"W 132°0'0"W Whale Passage Fisherman Chuck Point Howard Lemon Point Rock Ruins Point Point BarnesBush Rock The Triplets LinLcionlcno Rlno Icskland Rocky Bay Mosman PointFawn Island North Island Menefee Point Francis, Mount Deichman Rock Abraham Islands Deer IslandCDL Mabel Island Indian Creek South Island Hatchery Lake Niblack Islands Sarheen Cove Barnacle RockBeck Island Trout Creek Pyramid Peak Camp Taylor Rocky Bay Etolin, Mount Howard Cove Falls CreekTrout Creek Tokeen Peak Stevenson Island Gull Rock Three Way Passage Isle Point Kosciusko Island Lake Bay Seward Passage Indian Creek RapidsKeg Point Fairway Island Mabel Creek Holbrook Coffman Island Lake Bay Creek Stanhope Island Jadski Cove Holbrook Mountain McHenry Inlet El Capitan Passage Point Stanhope Grassy Lake Chum Creek Standing Rock Lake Range Island Barnes Lake Coffman Cove Shakes, Mount 56°0'0"N Canoe Passage Ernest Sound Santa Anna Inlet Tokeen Bay Entrance Island Brownson Island Cape Decsion Coffman Creek Point Santa Anna Tenass Pass Tenass Island Clarence Strait Point Peters TablSea Mntoau Anntanina Tokeen BrockSmpan bPearsgs Island Gold and Galligan Lagoon Quartz Rock Change IslandSunny Bay 56°0'0"N Rocky Cove Luck Point Helen, Lake Decision Passage Point Hardscrabble Van Sant Cove Clam Cove Galligan Creek Avon Island Clam Island McHenry Anchorage Watkins Point Burnt Island Tunga Inlet Eagle Creek Brockman Island Salt Water Lagoon Sweetwater Lake Luck Kelp Point Brownson Peak Fishermans Harbor FLO Marble Island Graveyard -

Professional Report

Table of Contents Executive Summary............................................................................................... - 2 - Introduction ........................................................................................................... - 3 - West Chichagof - Yakobi Wilderness (WCYW) .................................................... - 4 - Area Description ..................................................................................... - 4 - Commercial Visitor Use ............................................................ - 6 - Determination of Need for Commercial Services – Assumptions and Evaluation Criteria ................................................................... - 7 - Assumptions ............................................................................................ - 7 - Evaluation Criteria .................................................................................. - 8 - Wilderness Dependence .......................................................... - 8 - Potential Impacts to Wilderness Character ............................ - 8 - Knowledge, Skills, and Equipment Required .......................... - 11 - Visitor Safety ............................................................................. - 12 - Outfitter/Guide Demand and Utilization ................................ - 12 - Public Purposes / Management Objectives ........................... - 12 - Determination of Need for Commercial Services by Activity ............................ - 12 - Activities Considered .............................................................................