Two Flags and No Clue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John F. Morrison Phd Thesis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository 'THE AFFIRMATION OF BEHAN?' AN UNDERSTANDING OF THE POLITICISATION PROCESS OF THE PROVISIONAL IRISH REPUBLICAN MOVEMENT THROUGH AN ORGANISATIONAL ANALYSIS OF SPLITS FROM 1969 TO 1997 John F. Morrison A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2010 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/3158 This item is protected by original copyright ‘The Affirmation of Behan?’ An Understanding of the Politicisation Process of the Provisional Irish Republican Movement Through an Organisational Analysis of Splits from 1969 to 1997. John F. Morrison School of International Relations Ph.D. 2010 SUBMISSION OF PHD AND MPHIL THESES REQUIRED DECLARATIONS 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, John F. Morrison, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 82,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2005 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph.D. in May, 2007; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2005 and 2010. Date 25-Aug-10 Signature of candidate 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of Ph.D. -

A Fresh Start? the Northern Ireland Assembly Election 2016

A fresh start? The Northern Ireland Assembly election 2016 Matthews, N., & Pow, J. (2017). A fresh start? The Northern Ireland Assembly election 2016. Irish Political Studies, 32(2), 311-326. https://doi.org/10.1080/07907184.2016.1255202 Published in: Irish Political Studies Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright 2016 Taylor & Francis. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:30. Sep. 2021 A fresh start? The Northern Ireland Assembly election 2016 NEIL MATTHEWS1 & JAMES POW2 Paper prepared for Irish Political Studies Date accepted: 20 October 2016 1 School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK. Correspondence address: School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies, University of Bristol, 11 Priory Road, Bristol BS8 1TU, UK. -

Political Affairs Digest a Daily Summary of Political Events Affecting the Jewish Community

19 May 2021 Issue 2,123 Political Affairs Digest A daily summary of political events affecting the Jewish Community Contents Home Affairs Relevant Legislation Israel Consultations Foreign Affairs Back issues Home Affairs House of Commons Oral Answers Antisemitic Attacks col 411 Mr Speaker: Before I call the Secretary of State to respond to the urgent question, I have a short statement to make. I know that all Members will be deeply concerned by the footage of apparently antisemitic behaviour that appeared online yesterday. I understand that a number of individuals have been arrested in relation to the incident, but that no charges have yet been made. Therefore, the House’s sub judice resolution is not yet formally engaged. However, I remind all Members to exercise caution and avoid referring to the details of specific cases in order to avoid saying anything that might compromise any ongoing investigation or subsequent prosecution. … Robert Halfon (Conservative): To ask the Secretary of State for the Home Department if she will make a statement on recent antisemitic attacks across the UK. The Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government (Robert Jenrick): No one could fail to be appalled by the disgraceful scenes of antisemitic abuse directed at members of the Jewish community in the past week. In Chigwell, Rabbi Rafi Goodwin was hospitalised after being attacked outside his synagogue. In London, activists drove through Golders Green and Finchley, both areas with large Jewish populations, apparently shouting antisemitic abuse through a megaphone. These are intimidatory, racist and extremely serious crimes. The police have since made four arrests for racially aggravated public order offences and have placed extra patrols in the St John’s Wood and Golders Green areas. -

Five Years of Northern Ireland Humanists for a Kinder, More Rational Society

FIVE YEARS OF NORTHERN IRELAND HUMANISTS FOR A KINDER, MORE RATIONAL SOCIETY Northern Ireland Humanists is a section of Humanists UK, working with the Humanist Association of Ireland. Humanists UK is the national charity working on behalf of non-religious people. Powered by 100,000 members and supporters, we advance free thinking and promote humanism to create a tolerant society where rational thinking and kindness prevail. We provide ceremonies, pastoral care, education, and support services benefitting over a million people every year and our campaigns advance humanist thinking on ethical issues, human rights, and equal treatment for all. 2 3 FIVE YEARS OF NORTHERN IRELAND HUMANISTS Anniversary congratulations for ‘I congratulate Northern Ireland Northern Ireland Humanists have come Humanists on all the important work ‘Thank you for all of your endeavours they have done over the last number in from across the political spectrum towards an inclusive and equal of years around issues such as Northern Ireland and congratulations abortion rights, same-sex marriage on your fifth anniversary. We look and giving a voice to people who forward to working with you on many are normally excluded from political more campaigns including repealing discourse here. I wish them well on Northern Ireland’s blasphemy laws.’ their anniversary and I look forward to seeing the work they complete Naomi Long MLA over the next five years and beyond.’ ‘Congratulations to Northern ‘I would like to congratulate Northern Leader, Alliance Party Ireland Humanists on your fifth Ireland Humanists on your fifth Gerry Carroll MLA anniversary. You’ve achieved so anniversary. During that time, we People Before Profit much over these past five years have seen major changes in society and I’d like to thank you for the and important steps towards enormous contributions that equality here in the north. -

Critical Engagement: Irish Republicanism, Memory Politics

Critical Engagement Critical Engagement Irish republicanism, memory politics and policing Kevin Hearty LIVERPOOL UNIVERSITY PRESS First published 2017 by Liverpool University Press 4 Cambridge Street Liverpool L69 7ZU Copyright © 2017 Kevin Hearty The right of Kevin Hearty to be identified as the author of this book has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data A British Library CIP record is available print ISBN 978-1-78694-047-6 epdf ISBN 978-1-78694-828-1 Typeset by Carnegie Book Production, Lancaster Contents Acknowledgements vii List of Figures and Tables x List of Abbreviations xi Introduction 1 1 Understanding a Fraught Historical Relationship 25 2 Irish Republican Memory as Counter-Memory 55 3 Ideology and Policing 87 4 The Patriot Dead 121 5 Transition, ‘Never Again’ and ‘Moving On’ 149 6 The PSNI and ‘Community Policing’ 183 7 The PSNI and ‘Political Policing’ 217 Conclusion 249 References 263 Index 303 Acknowledgements Acknowledgements This book has evolved from my PhD thesis that was undertaken at the Transitional Justice Institute, University of Ulster (TJI). When I moved to the University of Warwick in early 2015 as a post-doc, my plans to develop the book came with me too. It represents the culmination of approximately five years of research, reading and (re)writing, during which I often found the mere thought of re-reading some of my work again nauseating; yet, with the encour- agement of many others, I persevered. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: SLAVE SHIPS, SHAMROCKS, AND SHACKLES: TRANSATLANTIC CONNECTIONS IN BLACK AMERICAN AND NORTHERN IRISH WOMEN’S REVOLUTIONARY AUTO/BIOGRAPHICAL WRITING, 1960S-1990S Amy L. Washburn, Doctor of Philosophy, 2010 Dissertation directed by: Professor Deborah S. Rosenfelt Department of Women’s Studies This dissertation explores revolutionary women’s contributions to the anti-colonial civil rights movements of the United States and Northern Ireland from the late 1960s to the late 1990s. I connect the work of Black American and Northern Irish revolutionary women leaders/writers involved in the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Black Panther Party (BPP), Black Liberation Army (BLA), the Republic for New Afrika (RNA), the Soledad Brothers’ Defense Committee, the Communist Party- USA (Che Lumumba Club), the Jericho Movement, People’s Democracy (PD), the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA), the Irish Republican Socialist Party (IRSP), the National H-Block/ Armagh Committee, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA), Women Against Imperialism (WAI), and/or Sinn Féin (SF), among others by examining their leadership roles, individual voices, and cultural productions. This project analyses political communiqués/ petitions, news coverage, prison files, personal letters, poetry and short prose, and memoirs of revolutionary Black American and Northern Irish women, all of whom were targeted, arrested, and imprisoned for their political activities. I highlight the personal correspondence, auto/biographical narratives, and poetry of the following key leaders/writers: Angela Y. Davis and Bernadette Devlin McAliskey; Assata Shakur and Margaretta D’Arcy; Ericka Huggins and Roseleen Walsh; Afeni Shakur-Davis, Joan Bird, Safiya Bukhari, and Martina Anderson, Ella O’Dwyer, and Mairéad Farrell. -

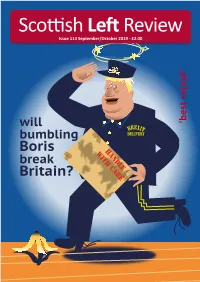

Scottish Leftreview

ScottishLeft Review Issue 113 September/October 2019 - £2.00 'best re(a)d' 'best 1 - ScottishLeftReview Issue 113 September/October 2019 ASLEF CALLS FOR AN INTEGRATED, PUBLICLY OWNED, ACCOUNTABLE RAILWAY FOR SCOTLAND (which used to be the SNP’s position – before they became the government!) Mick Whelan Tosh McDonald Kevin Lindsay General Secretary President Scottish Ocer ASLEF the train drivers union- www.aslef.org.uk STUC 2018_Layout 1 09/01/2019 10:04 Page 1 Britain’s specialist transport union Campaigning for workers in the rail, maritime, offshore/energy, bus and road freight sectors NATIONALISE SCOTRAIL www.rmt.org.uk 2 - ScottishLeftReview Issue 113 September/OctoberGeneral 2019Secretary: Mick Cash President: Michelle Rodgers feedback comment Like many others, Scottish Left Review is outraged at the attack on democracy represented by prorogation and condemns this extended suspension of Parliament to allow for a no-deal Brexit to be forced through without any parliamentary scrutiny or the opportunity for parliamentary opposition. Scottish Left Review supports initiatives to mobilise citizens outside of Parliament to confront this anti-democratic outrage. We call on all opposition MPs and Tory MPs who believe in parliamentary democracy to join together to defeat this outrage. All the articles in this issue (bar Kick up the Tabloids) were written before reviewsthe prorogation on 28 August 2019. t has long been a shibboleth on the Who will benefit from Brexit? of contradictions. This is certainly true radical left, following from Marx and as Boris seems to be prepared to engage In the lead article in this issue, George Engels, that politics in the last instance in Keynesian-style reflation to try to aid I Kerevan explains this perplexing situation bends to the will of economics. -

Official Report (Hansard)

Official Report (Hansard) Tuesday 25 February 2020 Volume 125, No 9 Session 2019-2020 Contents Executive Committee Business Budget Bill: Second Stage ................................................................................................................. 1 Oral Answers to Questions Finance .............................................................................................................................................. 28 Health ................................................................................................................................................ 37 Executive Committee Business Budget Bill: Second Stage (Continued) ............................................................................................. 46 Assembly Members Aiken, Steve (South Antrim) Kearney, Declan (South Antrim) Allen, Andy (East Belfast) Kelly, Ms Catherine (West Tyrone) Allister, Jim (North Antrim) Kelly, Mrs Dolores (Upper Bann) Anderson, Ms Martina (Foyle) Kelly, Gerry (North Belfast) Archibald, Dr Caoimhe (East Londonderry) Kimmins, Ms Liz (Newry and Armagh) Armstrong, Ms Kellie (Strangford) Long, Mrs Naomi (East Belfast) Bailey, Ms Clare (South Belfast) Lunn, Trevor (Lagan Valley) Barton, Mrs Rosemary (Fermanagh and South Tyrone) Lynch, Seán (Fermanagh and South Tyrone) Beattie, Doug (Upper Bann) Lyons, Gordon (East Antrim) Beggs, Roy (East Antrim) Lyttle, Chris (East Belfast) Blair, John (South Antrim) McAleer, Declan (West Tyrone) Boylan, Cathal (Newry and Armagh) McCann, Fra (West Belfast) Bradley, Maurice (East -

Find Your Local MLA

Find your local MLA Mr John Stewart UUP East Antrim 95 Main Street Larne Acorn Integrated Primary BT40 1HJ Carnlough Integrated Primary T: 028 2827 2644 Corran Integrated Primary [email protected] Ulidia Integrated College Mr Roy Beggs UUP 3 St. Brides Street Carrickfergus BT38 8AF 028 9336 2995 [email protected] Mr Stewart Dickson Alliance 8 West Street Carrickfergus BT38 7AR 028 9335 0286 [email protected] Mr David Hilditch DUP 2 Joymount Carrickfergus BT38 7DN 028 9332 9980 [email protected] Mr Gordon Lyons DUP 116 Main Street Larne Co. Antrim BT40 1RG 028 2826 7722 [email protected] Mr Robin Newton DUP East Belfast 59 Castlereagh Road Ballymacarret Lough View Integrated Primary Belfast BT5 5FB Mr Andrew Allen UUP 028 9045 9500 [email protected] 174 Albertbridge Road Belfast BT5 4GS 028 9046 3900 [email protected] Ms Joanne Bunting DUP 220 Knock Road Carnamuck Belfast BT5 6QD 028 9079 7100 [email protected] Mrs Naomi Long 56 Upper Newtownards Road Ballyhackamore Belfast BT4 3EL 028 9047 2004 [email protected] Mr Chris Lyttle Alliance 56 Upper Newtownards Road Ballyhackamore Belfast BT4 3EL 028 9047 2004 [email protected] Miss Claire Sugden Independent East Londonderry 1 Upper Abbey Street Coleraine Carhill Integrated Primary BT52 1BF Mill Strand Integrated Primary 028 7032 7294 Roe Valley Integrated Primary [email protected] North Coast Integrated College -

July 19, 2018, Vol. 60, No. 29

Guerra arancelaria; Fórmula capitalista mata bebés 12 Workers and oppressed peoples of the world unite! workers.org Vol. 60, No. 29 July 19, 2018 $1 Wales, England, Scotland Huge protests slam U.S. prez By Kathy Durkin A massive crowd of 250,000 people protested Presi- dent Donald Trump’s visit to Britain on July 13 in Lon- FIRE vs. U.S. border policies don, says the Stop Trump Coalition. The group was a main organizer of Together Against Trump demonstra- tions. Though dubbed “the Carnival of Resistance,” the is- sues raised were serious: opposition to Trump’s racism, Islamophobia, misogyny, and immigration and envi- ronmental policies, including U.S. withdrawal from the Paris climate control accord. Signs also slammed Brit- ain’s Brexit policy for its xenophobia. Owen Jones, a coalition leader, explained: “We need to show that we abhor everything that Trump represents: bigotry, racism, anti-Muslim prejudice and misogyny.” (New York Times, July 13) The Women’s March London kicked off the protests prior to the main demonstration. With the theme of “Bring the Noise” — drums, whistles, pots and pans — women said loudly and clearly that “this misogynist is not welcome here.” Stonewall, the LGBTQ rights charity, had a large contingent and denounced Trump’s attacks on their rights in the U.S. Later in the day, demonstra- tors, including many Muslims, marched across London. Huge banners were held aloft that read, “Trump not welcome here!” while sign and chant slogans said, “Ref- WW PHOTO: BRENDA RYAN ugees are welcome here!” The new organization, FIRE, demonstrates at Rockefeller Center to protest DHS and ICE dinner in New York City, July 11. -

Fianna Fáil: Past and Present Alan Byrne 57

Irish Marxist Review Editor: John Molyneux Deputy Editor: Dave O’Farrell Website Editor: Memet Uludag Editorial Board: Marnie Holborow, Sinéad Kennedy, Tina MacVeigh, Paul O’Brien, Peadar O’Grady Cover Design: Daryl Southern Published: November 2016 SWP PO.Box 1648 Dublin 8 Phone: John Molyneux 085 735 6424 Email: [email protected] Website: www.irishmarxistreview.net Irish Marxist Review is published in association with the Socialist Workers Party (Ireland), but articles express the opinions of individual authors unless otherwise stated. We welcome proposals for articles and reviews for IMR. If you have a suggestion please phone or email as above. i Irish Marxist Review 16 Contents Editorial 1 Equality, Democracy, Solidarity: The Politics of Abortion Melisa Halpin and Peadar O’Grady 3 Into the limelight: tax haven Ireland Kieran Allen 14 Can the European Union be reformed? Marnie Holborow 28 Secularism, Islamophobia and the politics of religion John Molyneux 41 A Socialist in Stormont An interview with Gerry Carroll MLA 52 Fianna Fáil: Past and Present Alan Byrne 57 The socialist tradition in the disability movement: Lessons for contemporary activists Ivanka Antova 65 Science, Politics and Public Policy Dave O’Farrell 70 The Starry Plough – a historical note Damian Lawlor 76 Review: Kieran Allen, The Politics of James Connolly Shaun Doherty 78 Review: Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, From #Black Lives Matter to Black Liberation Conor Kennelly 80 ii Editorial: Interesting Times ‘May you live in interesting times’ is a lishment’s talk of recovery has given rise, well known Chinese curse. These are cer- not surprisingly, to workers demanding their tainly interesting times in Ireland at the mo- share. -

A Decade of Change

A Decade of Change Law Centre NI Annual Social Security Law & Practice Conference 2020 E V E N T P R O G R A M M E A D E C A D E O F C H A N G E : O V E R V I E W E V E N T O V E R V I E W 10:00 - 10:20 Conference opening DAY 01 Ursula O'Hare | Cáral Ní Chuilín 10:20 - 11:10 Plenary session Social Security 2010–2020: A Koulla Yiassouma | Janet Hunter | Les Allamby Changed and Changing Landscape 11:10 - 11:15 Break 11:15 - 12:00 Practitioner workshops Opening with an address from the Minister for Housing benefit vs universal credit | Current legal issues | Communities, day one will look at the impact that Tackling disparate impact: the impact on women ten years of welfare reform has had on people in NI, 12:05 - 12:15 Closing remarks hearing perspectives on children and young people, housing, human rights and more. 10:00 - 10:20 Welcome & keynote speech Linda McAuley | Iain Porter DAY 02 10:20 - 11:10 Plenary session Marie Cavanagh | Margaret Kelly | Prof Gráinne McKeever Current Priorities 11:10 - 11:15 Break 11:15 - 12:00 Practitioner workshops Day two will look at current priorities around poverty, Covid-19 and PIP. Delegates will hear Ending food poverty | Personal independence payment about the Covid-19 review by the Social Security | Advising NRPF clients Advisory Committee and have the option to attend 12:05 - 12:15 Closing remarks workshops on poverty, PIP and NRPF.