Thelma Shelton Robinson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Focus Winter 2002/Web Edition

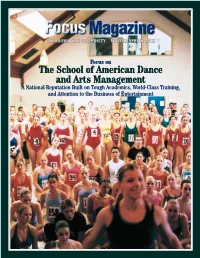

OKLAHOMA CITY UNIVERSITY • WINTER/SPRING 2002 Focus on The School of American Dance and Arts Management A National Reputation Built on Tough Academics, World-Class Training, and Attention to the Business of Entertainment Light the Campus In December 2001, Oklahoma’s United Methodist university began an annual tradition with the first Light the Campus celebration. Editor Robert K. Erwin Designer David Johnson Writers Christine Berney Robert K. Erwin Diane Murphree Sally Ray Focus Magazine Tony Sellars Photography OKLAHOMA CITY UNIVERSITY • WINTER/SPRING 2002 Christine Berney Ashley Griffith Joseph Mills Dan Morgan Ann Sherman Vice President for Features Institutional Advancement 10 Cover Story: Focus on the School John C. Barner of American Dance and Arts Management Director of University Relations Robert K. Erwin A reputation for producing professional, employable graduates comes from over twenty years of commitment to academic and Director of Alumni and Parent Relations program excellence. Diane Murphree Director of Athletics Development 27 Gear Up and Sports Information Tony Sellars Oklahoma City University is the only private institution in Oklahoma to partner with public schools in this President of Alumni Board Drew Williamson ’90 national program. President of Law School Alumni Board Allen Harris ’70 Departments Parents’ Council President 2 From the President Ken Harmon Academic and program excellence means Focus Magazine more opportunities for our graduates. 2501 N. Blackwelder Oklahoma City, OK 73106-1493 4 University Update Editor e-mail: [email protected] The buzz on events and people campus-wide. Through the Years Alumni and Parent Relations 24 Sports Update e-mail: [email protected] Your Stars in action. -

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

Aaamc Issue 9 Chrono

of renowned rhythm and blues artists from this same time period lip-synch- ing to their hit recordings. These three aaamc mission: collections provide primary source The AAAMC is devoted to the collection, materials for researchers and students preservation, and dissemination of materi- and, thus, are invaluable additions to als for the purpose of research and study of our growing body of materials on African American music and culture. African American music and popular www.indiana.edu/~aaamc culture. The Archives has begun analyzing data from the project Black Music in Dutch Culture by annotating video No. 9, Fall 2004 recordings made during field research conducted in the Netherlands from 1998–2003. This research documents IN THIS ISSUE: the performance of African American music by Dutch musicians and the Letter ways this music has been integrated into the fabric of Dutch culture. The • From the Desk of the Director ...........................1 “The legacy of Ray In the Vault Charles is a reminder • Donations .............................1 of the importance of documenting and • Featured Collections: preserving the Nelson George .................2 achievements of Phyl Garland ....................2 creative artists and making this Arizona Dranes.................5 information available to students, Events researchers, Tribute.................................3 performers, and the • Ray Charles general public.” 1930-2004 photo by Beverly Parker (Nelson George Collection) photo by Beverly Parker (Nelson George Visiting Scholars reminder of the importance of docu- annotation component of this project is • Scot Brown ......................4 From the Desk menting and preserving the achieve- part of a joint initiative of Indiana of the Director ments of creative artists and making University and the University of this information available to students, Michigan that is funded by the On June 10, 2004, the world lost a researchers, performers, and the gener- Andrew W. -

Guide to the Michigan Dance Archives: Harriet Berg Papers UP001608

Guide to the Michigan Dance Archives: Harriet Berg Papers UP001608 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on June 11, 2018. English Describing Archives: A Content Standard Walter P. Reuther Library 5401 Cass Avenue Detroit, MI 48202 URL: https://reuther.wayne.edu Guide to the Michigan Dance Archives: Harriet Berg Papers UP001608 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 History ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 6 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 7 Collection Inventory ...................................................................................................................................... -

68403 NABS Newsletter.Indd

National Association of Black Storytellers P.O. Box 67722 Baltimore, Maryland 21215 www.nabsinc.org Fall 2008 Co-Founders Mary Carter Smith Linda Goss STORYTELLING: Board of Directors Co-Founder Medicine for the Spirit, Healing for the Soul! Linda Goss Philadelphia, PA (From “A Storyteller’s Rap” in Talk That Talk) President Dylan Pritchett Dear NABS Family, Williamsburg, VA President-Elect During the early days of September as the leaves were beginning to fall, I Vanora Legaux began receiving phone calls from several friends expressing their frustrations and anxieties about the Gretna, LA 2008 Presidential campaign. One morning, the calls began around 8:30 AM and by noon I was feeling Treasurer so overwhelmed that I was jumping every time I heard a ringing sound. Robert Smith, Jr. Baltimore, MD Then I received a call from our Executive Director, Linda Jenkins Brown, who informed me that a Secretary storyteller named Susi Wolf, from Albuquerque, New Mexico, had made a contribution to NABS in MaryAnn Harris East Cleveland, OH appreciation for the great stories from “Mother Africa.” Immediate Past President Later that evening, around 9 PM EST, I phoned Susi to thank her. When she answered I said, ‘IT’S Barbara Eady STORYTELLING TIME!’ From that point on, a doorway opened before us and we were led on a Cleveland, OH path of mysteries, dreams and fables. We talked for about fi ve hours….until 2AM! T. Nokware Adesegun Snellville, GA Susi Wolf is a powerful storyteller who has a calming and soothing way of sharing a story. She is Akbar Imhotep Cherokee and tells healing stories from around the world. -

The Social and Cultural Changes That Affected the Music of Motown Records from 1959-1972

Columbus State University CSU ePress Theses and Dissertations Student Publications 2015 The Social and Cultural Changes that Affected the Music of Motown Records From 1959-1972 Lindsey Baker Follow this and additional works at: https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Baker, Lindsey, "The Social and Cultural Changes that Affected the Music of Motown Records From 1959-1972" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 195. https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations/195 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at CSU ePress. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSU ePress. The Social and Cultural Changes that Affected the Music of Motown Records From 1959-1972 by Lindsey Baker A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements of the CSU Honors Program for Honors in the degree of Bachelor of Music in Performance Schwob School of Music Columbus State University Thesis Advisor Date Dr. Kevin Whalen Honors Committee Member ^ VM-AQ^A-- l(?Yy\JcuLuJ< Date 2,jbl\5 —x'Dr. Susan Tomkiewicz Dean of the Honors College ((3?7?fy/L-Asy/C/7^ ' Date Dr. Cindy Ticknor Motown Records produced many of the greatest musicians from the 1960s and 1970s. During this time, songs like "Dancing in the Street" and "What's Going On?" targeted social issues in America and created a voice for African-American people through their messages. Events like the Mississippi Freedom Summer and Bloody Thursday inspired the artists at Motown to create these songs. Influenced by the cultural and social circumstances of the Civil Rights Movement, the musical output of Motown Records between 1959 and 1972 evolved from a sole focus on entertainment in popular culture to a focus on motivating social change through music. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1993

L T 1 TO THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES: It is my special pleasure to transmit herewith the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts for the fiscal year 1993. The National Endowment for the Arts has awarded over 100,000 grants since 1965 for arts projects that touch every community in the Nation. Through its grants to individual artists, the agency has helped to launch and sustain the voice and grace of a generation--such as the brilliance of Rita Dove, now the U.S. Poet Laureate, or the daring of dancer Arthur Mitchell. Through its grants to art organizations, it has helped invigorate community arts centers and museums, preserve our folk heritage, and advance the perform ing, literary, and visual arts. Since its inception, the Arts Endowment has believed that all children should have an education in the arts. Over the past few years, the agency has worked hard to include the arts in our national education reform movement. Today, the arts are helping to lead the way in renewing American schools. I have seen first-hand the success story of this small agency. In my home State of Arkansas, the National Endowment for the Arts worked in partnership with the State arts agency and the private sector to bring artists into our schools, to help cities revive downtown centers, and to support opera and jazz, literature and music. All across the United States, the Endowment invests in our cultural institutions and artists. People in communities small and large in every State have greater opportunities to participate and enjoy the arts. -

2019 Annual Report

\ 2019 ANNUAL REPORT Janice Curtis Greene 16th President, National Association of Black Storytellers 2019 Board National Association of Black Storytellers Our Mission Co-Founder Mama Linda Goss The National Association of Black Storytellers, Inc. (NABS) promotes and Executive Director Vanora F. Legaux perpetuates the art of Black storytelling--an President Janice Curtis Greene art form which embodies the history, heritage, and culture of African Americans. President Elect Kwanza Brewer Black storytellers educate and entertain Sercretary Janice Burnett through the Oral Tradition, which depicts and documents the African-American experience. Treasurer Gwen Hilary A nationally organized body with individual, Immediate Past President Sandra Gilliard affiliate and organizational memberships, NABS preserves and passes on the folklore, Member Rosa Metoyer legends, myths, fables and mores of Africans Member Steven Hobbs and their descendants and ancestors - "In the Member Beverly Fields Burnett Tradition..." Member Beverly Cottman During 2019 NABS celebrated both Co-Founders NABS Started the year 2019 celebrating Our Ancestor Co-founder Mother Mary Carter Smith's Picture from 2019 Festival Youth 100th birthday February 10, 1919 - February 10, 2019 Proclaiming 2019 The Year of Mother Mary Carter Smith Celebrations, Worship Services, Concerts and Performances were held by 9 of NABS's 15 Affiliates, during February at the th 37 NABS Festival & Conference in Montgomery, Alabama and throughout the year. History Made! On September 18, 2019 Co-Founder, Mama Linda Goss was awarded the National Heritage Fellowship in Storytelling from the National Endowment for the Arts. NABS’s 2019 Membership totals 350 with 58 Regular Members, 176 Elder Members, 17 Youth Members, 62 silver life members, 29 gold life members, 3 organizational members and 5 contributing members. -

BLACK GIRL: Linguistic Play

Reference and Resource Guide Camille A. Brown’s BLACK GIRL: Linguistic Play draws from dance, music, and hand game traditions of West and Sub-Saharan African cultures, as fltered through generations of the African- American experience. The result is a depiction of the complexities in carving out a positive identity as a black female in today’s urban America. The core of this multimedia work is a unique blend of body percussion, rhythmic play, gesture, and self-expression that creates its own lexicon. The etymology of her linguistic play can be traced from pattin’ Juba, buck and wing, social dances and other percussive corollaries of the African drum found on this side of the Atlantic, all the way to jumping double dutch, and dancing The Dougie. Brown uses the rhythmic play of this African-American dance vernacular as the black woman’s domain to evoke childhood memories of self-discovery. Hambone, hambone, where you been? Around the world and back again Let’s use the hambone lyric as a metaphor for what happened culturally to song and dance forms developed in African-American enclaves during the antebellum era. The hambone salvaged from the big house meal made its way to cabins and quarters of enslaved Africans, depositing and transporting favors from soup pot to soup pot, family to family, generation to generation, and providing nourishment for the soul and for the struggle. When dancing and drumming were progressively banned during the 18th century, black people used their creativity and inventiveness to employ their bodies as a beatbox for song and dance. -

Dorrance Dance Program

Corporate Season Sponsor: Dorrance Dance Michelle Dorrance, Artistic Director Wed, Mar 8 / 8 PM / Granada Theatre Dance Series Sponsors: Annette & Dr. Richard Caleel Margo Cohen-Feinberg & Robert Feinberg and the Cohen Family Fund Irma & Morrie Jurkowitz Barbara Stupay Corporate Sponsor: The Lynda and Bruce Thematic Learning Initiative: Creative Culture ACT I Excerpts from SOUNDspace (2013)* I have had the honor of studying with and spending time with a great number of our tap masters before they passed Direction and Choreography: Michelle Dorrance, with solo away: Maceo Anderson, Dr. Cholly Atkins, Clayton “Peg- improvisation by the dancers Leg” Bates, Dr. James “Buster” Brown, Ernest “Brownie” Brown, Harriet “Quicksand” Browne, Dr. Harold Cromer, Dancers: Ephrat “Bounce” Asherie, Elizabeth Burke, Gregory Hines, Dr. Jeni Legon, Dr. Henry LeTang, LeRoy Warren Craft, Michelle Dorrance, Carson Murphy, Myers, Dr. Fayard and Harold Nicholas, Donald O’Connor, Dr. Leonard Reed, Jimmy Slyde and Dr. Prince Spencer. Leonardo Sandoval, Byron Tittle, Nicholas Van Young I would also like to honor our living masters whom I am constantly influenced by: Arthur Duncan, Dr. Bunny Briggs, *Originally a site-specific work that explored the unique acoustics of New Brenda Bufalino, Skip Cunningham, Miss Mable Lee and Dianne Walker. York City’s St. Mark’s Church through the myriad sounds and textures of the feet, “SOUNDspace” has been adapted and continues to explore what is most While we are exploring new ideas in this show, we are also beautiful and exceptional about tap dancing – movement as music. constantly mindful of our rich history. Dr. Jimmy Slyde was The creation of “SOUNDspace” was made possible, in part, by the Danspace the inspiration for my initial exploration of slide work in Project 2012-2013 Commissioning Initiative, with support from the New York socks (in the original work) and his influence continues to State Council on the Arts. -

Dorrance Dance Sponsored by Sherman Capital Markets, Llc

48 DANCE DORRANCE DANCE SPONSORED BY SHERMAN CAPITAL MARKETS, LLC SOUNDspace Memminger Auditorium May 31 and June 7 at 8:00pm; June 7 and 8 at 2:30pm Artistic Director and Choreographer Michelle Dorrance, with improvisational solo work by dancers Production Manager/Technical Director Tony Mayes Lighting Designer Kathy Kaufmann Assistant Stage/Production Manager Ali Dietz Costumes Mishay Petronelli Original Live Music Greg Richardson Original Body Percussion Score Nicholas Young Dancers Megan Bartula Elizabeth Burke Warren Craft Ali Dietz (Understudy) Michelle Dorrance Karida Griffith Logan Miller Demi Remick Caleb Teicher Byron Tittle Nicholas Young PERFORMED WITHOUT AN INTERMISSION. Originally a site-specific work that explored the unique acoustics of New York City’s St. Mark’s church through the myriad sounds and textures of the feet, SOUNDspace has been adapted specifically for Spoleto Festival USA and continues to explore what is most beautiful and exceptional about tap dancing—movement as music. DORRANCE DANCE 49 DELTA TO DUSK Memminger Auditorium June 1, 2, 5, and 6 at 8:00pm; June 3 at 7:00pm Artistic Director and Choreographer Michelle Dorrance, with improvisational solo work by dancers Production Manager/Technical Director Tony Mayes Lighting Designer Kathy Kaufmann Assistant Stage/Production Manager Ali Dietz Costumes Mishay Petronelli, Michelle Dorrance, Andrew Jordan Music Toshi Reagon, Etta James, Muddy Waters, Chris Whitley, The Beatles, Regina Spektor, Fiona Apple, the Squirrel Nut Zuppers, Manu Chao, Radiohead,Stevie Wonder. Dancers Megan Bartula Elizabeth Burke Warren Craft Ali Dietz (Understudy) Michelle Dorrance Karida Griffith Logan Miller Carson Murphy Claudia Rahardjanoto Demi Remick Caleb Teicher Byron Tittle Nicholas Young PERFORMED WITHOUT AN INTERMISSION. -

Fall 2019 Issue

Spotlight on Montana’s Symphonies Pages 14-15 U.S. Poet Laureate Joy Harjo in Billings Page 17 Fall 2019 n Montana - The Land of Creativity MAC NEWS Crow storyteller Grant Bulltail named National Heritage Fellow Crow storyteller Grant Bulltail is among the National Endowment for the Arts 2019 National Heritage Fellows, recipients of the nation’s highest honor in the folk and traditional arts. Each fellowship includes an award of $25,000 and the recipients were honored at two public events on Sept. 18 and 20 Poets Laureate Melissa Kwasny and M.L. Smoker in Washington, D.C. (Photo by Barbara Weissberger) Bulltail joins Heritage Fel- lows Dan Ansotegui, a Basque Montana Poets Laureate musician and tradition bearer Melissa Kwasny and M.L. Smoker from Boise, ID; Linda Goss, an African-American storyteller share title and responsibilities from Baltimore, MD; James F. Melissa Kwasny and M.L. Smoker were appointed Jackson, a leatherworker from National Heritage Fellow Grant Bulltail (Photo by Gary Wortman, EveryMan Productions) by Gov. Steve Bullock in July as Montana’s next poets Sheridan, WY; Balla Kouyaté, His Crow name is Bishéessawaache (The One Who laureate – and the first to share the position since it was a balafon player and djeli from Medford, MA; Josephine Sits Among the Buffalo), a name given him by his grand- established in 2005. Lobato, a Spanish colcha embroiderer from Westminster, father. He is a member of the Crow Culture Commission “The Montana Arts Council is inspired by this innova- CO; Rich Smoker, a decoy carver from Marion Station, at Crow Agency, a Lodge Erector and Pipe Carrier in tive approach and encouraged by Gov.