The Shipping Law Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on the Human Rights Situation in Ukraine 16 May to 15 August 2018

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Report on the human rights situation in Ukraine 16 May to 15 August 2018 Contents Page I. Executive summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 II. OHCHR methodology ...................................................................................................................... 3 III. Impact of hostilities .......................................................................................................................... 3 A. Conduct of hostilities and civilian casualties ............................................................................. 3 B. Situation at the contact line and rights of conflict-affected persons ............................................ 7 1. Right to restitution and compensation for use or damage of private property ..................... 7 2. Right to social security and social protection .................................................................... 9 3. Freedom of movement, isolated communities and access to basic services ...................... 10 IV. Right to physical integrity ............................................................................................................... 11 A. Access to detainees and places of detention ............................................................................ 11 B. Arbitrary detention, enforced disappearance and abduction, torture and ill-treatment ............... 12 C. Situation -

Ukraine 16 May to 15 August 2015

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Report on the human rights situation in Ukraine 16 May to 15 August 2015 CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 II. RIGHTS TO LIFE, LIBERTY, SECURITY AND PHYSICAL INTEGRITY 7 A. Casualties 7 B. Civilian casualties 8 C. Total casualties (civilian and military) from mid-April 2014 to 15 August 2015 12 D. Unlawful and arbitrary detention, summary executions, and torture and ill-treatment 13 III. FUNDAMENTAL FREEDOMS 18 A. Freedom of movement 18 B. Freedom of expression 19 C. Freedom of peaceful assembly 20 D. Freedom of association 21 E. Freedom of religion or belief 22 IV. ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL RIGHTS 22 A. Right to an adequate standard of living 23 B. Right to social security and protection 24 C. Right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health 26 V. ACCOUNTABILITY AND ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE 27 A. Accountability for human rights violations committed in the east of Ukraine 27 B. Accountability for human rights violations committed during the Maidan protests 30 C. Accountability for the 2 May violence in Odesa 30 D. Administration of justice 32 VI. LEGISLATIVE DEVELOPMENTS AND INSTITUTIONAL REFORMS 34 VII. HUMAN RIGHTS IN THE AUTONOMOUS REPUBLIC OF CRIMEA 38 VIII. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 42 I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. This is the eleventh report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) on the situation of human rights in Ukraine, based on the work of the United Nations Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine (HRMMU) 1. It covers the period from 16 May to 15 August 2015 2. -

Urgently for Publication (Procurement Procedures) Annoucements Of

Bulletin No�4 (183) January 28, 2014 Urgently for publication Annoucements of conducting (procurement procedures) procurement procedures 001143 000833 Luhansk National Agrarian University SOE “Prydniprovska Railway” 91008 Luhansk, Luhansk National Agrarian University 108 Karla Marksa Ave., 49600 Dnipropetrovsk Yevsiukova Liudmyla Semenivna, Bublyk Maryna Borysivna Ivanchak Serhii Volodymyrovych tel.: (095) 532–41–16; tel.: (056) 793–05–28; tel./fax: (0642) 96–77–64; tel./fax: (056) 793–00–41 e–mail: [email protected] Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: www.tender.me.gov.ua www.tender.me.gov.ua Website which contains additional information on procurement: www. tender. uz.gov.ua Website which contains additional information on procurement: www.lnau.lg.ua Procurement subject: code 33.17.1 – repair and maintenance of other Procurement subject: code 06.20.1 – natural gas, liquefied or in a gaseous vehicles and equipment (services in modernization of machine ВПР–02 state (gas exclusively for production of heat energy which is consumed with conducting major repair) – 1 unit by budget institutions and organizations), 1327,0 thousand m3 Supply/execution: on the territory of the winner of the bids; during 10 months from Supply/execution: at the customer’s address; till 31.12.2014 the moment of signing the act of delivery of track machine to modernization with Procurement procedure: procurement from the sole participant repair, but -

1 Introduction

State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES For map and other editors For international use Ukraine Kyiv “Kartographia” 2011 TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES FOR MAP AND OTHER EDITORS, FOR INTERNATIONAL USE UKRAINE State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Prepared by Nina Syvak, Valerii Ponomarenko, Olha Khodzinska, Iryna Lakeichuk Scientific Consultant Iryna Rudenko Reviewed by Nataliia Kizilowa Translated by Olha Khodzinska Editor Lesia Veklych ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ © Kartographia, 2011 ISBN 978-966-475-839-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ................................................................ 5 2 The Ukrainian Language............................................ 5 2.1 General Remarks.............................................. 5 2.2 The Ukrainian Alphabet and Romanization of the Ukrainian Alphabet ............................... 6 2.3 Pronunciation of Ukrainian Geographical Names............................................................... 9 2.4 Stress .............................................................. 11 3 Spelling Rules for the Ukrainian Geographical Names....................................................................... 11 4 Spelling of Generic Terms ....................................... 13 5 Place Names in Minority Languages -

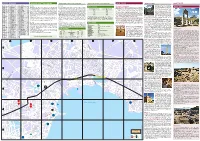

1 2 3 4 5 a B C D E

STREET REGISTER ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND WHAT TO SEE WHAT TO SEE WHAT TO SEE Amurskaya E/F-2 Krasniy Spusk G-3 Radishcheva E-5 By Bus By Plane Great Mitridat Stairs C-4, near the Lenina Admirala Vladimirskogo E/F-3 Khersonskaya E/F-3 Rybatskiy prichal D/C-4-B-5 Churches & Cathedrals pl. The stairs were built in the 1930’s with plans Ancient Cities Admirala Azarova E-4/5 Katernaya E-3 Ryabova F-4 Arriving by bus is the only way to get to Kerch all year round. The bus station There is a local airport in Kerch, which caters to some local Crimean flights Ferry schedule Avdeyeva E-5 Korsunskaya E-3 Repina D-4/5 Church of St. John the Baptist C-4, Dimitrova per. 2, tel. (+380) 6561 from the Italian architect Alexander Digby. To save Karantinnaya E-3 Samoylenko B-3/4 itself is a buzzing place thanks to the incredible number of mini-buses arriving during the summer season, but the only regular flight connection to Kerch is you the bother we have already counted them; Antonenko E-5 From Kerch (from Port Krym) To Kerch (from Port Kavkaz) 222 93. This church is a unique example of Byzantine architecture. It was built in Admirala Fadeyeva A/B-4 Kommunisticheskaya E-3-F-5 Sladkova C-5 and departing. Marshrutkas run from here to all of the popular destinations in through Simferopol State International, which has regular flights to and from Kyiv, there are 432 steps in all meandering from the Dep. -

Pdf | 1.05 Mb | A/Hrc/34/Crp.5

A/HRC/34/CRP.5 Distr.: Restricted 16 March 2017 English only Human Rights Council Thirty-fourth session 27 February-24 March 2017 Agenda item 10 Technical assistance and capacity-building Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the human rights situation in Ukraine * (16 November 2016 to 15 February 2017) * Reproduced as received. GE.17-04270(E) ∗1704270∗ A/HRC/34/CRP.5 Contents Paragraphs Page I. Executive summary ................................................................................................. 1–17 5 II. Rights to life, liberty, security and physical integrity .............................................. 18–62 8 A. International humanitarian law in the conduct of hostilities ........................... 18–27 8 B. Casualties ........................................................................................................ 28–33 10 C. Missing persons .............................................................................................. 34–36 12 D. Summary executions, disappearances, arbitrary detention, and torture and ill-treatment ........................................................................... 37–62 13 1. Summary executions ........................................................................... 38–39 13 2. Enforced disappearances and abductions .......................................... 40–41 13 3. Unlawful and arbitrary detention, torture and ill-treatment .............. 42–50 14 4. Access to places of detention ............................................................. -

Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the Human Rights Situation in Ukraine*

A/HRC/36/CRP.2 Distr.: Restricted 15 September 2017 English only Human Rights Council Thirty-sixth session 11-29 September 2017 Agenda item 10 Technical assistance and capacity-building Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the human rights situation in Ukraine* (16 May to 15 August 2017) * Reproduced as received. GE.17-16213(E) A/HRC/36/CRP.2 2 A/HRC/36/CRP.2 Response of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia to the contents of the report of the Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights on his mission to Saudi Arabia from 8 to 19 January 2017 1. First of all, the Kingdom wishes to express its gratitude to Professor Philip Alston, the Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, while emphasizing that its cooperation with him was consistent with its resolute desire to support all endeavours aimed at enabling individuals to enjoy their basic rights since the Kingdom is diligently and consistently seeking to ensure that human rights are respected and enjoyed by all citizens and foreign residents in its territory. It therefore appreciates the views that he presented in his report, on which there will be appropriate follow-up. 2. Further to the preliminary comments which the Kingdom submitted on 4 April 2017 with a view to correcting some of the information, data and views contained in his report pending the preparation of fuller and more detailed comments on the information, data, observations and recommendations presented therein, including some of the statistical figures which were based on undocumented or outdated sources, the Kingdom is submitting in this present report a more comprehensive response to the report of the Special Rapporteur on his mission to Saudi Arabia from 8 to 19 January 2017. -

Report on the Human Rights Situation in Ukraine 16 February to 15 May 2015

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Report on the human rights situation in Ukraine 16 February to 15 May 2015 CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 II. RIGHTS TO LIFE, LIBERTY, SECURITY AND PHYSICAL INTEGRITY 6 A. Armed hostilities 6 B. Casualties 7 C. Alleged summary, extrajudicial or arbitrary executions 8 D. Illegal and arbitrary detention, and torture and ill-treatment 9 E. Trafficking in persons 13 III. FUNDAMENTAL FREEDOMS 14 A. Freedom of movement 14 B. Freedom of expression 15 C. Freedom of peaceful assembly 17 IV. ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL RIGHTS 18 A. Right to an adequate standard of living 18 B. Right to social protection 19 C. Right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health 21 V. ACCOUNTABILITY AND ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE 21 A. Accountability for human rights violations in the east 22 B. Accountability for human rights violations committed during the Maidan protests 23 C. Accountability for the 2 May violence in Odesa 25 D. Investigation into Rymarska case 26 E. Administration of justice 27 VI. LEGISLATIVE DEVELOPMENTS AND INSTITUTIONAL REFORMS 29 VII. HUMAN RIGHTS IN THE AUTONOMOUS REPUBLIC OF CRIMEA 33 VIII. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 36 2 I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. This is the tenth report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) on the situation of human rights in Ukraine, based on the work of the United Nations Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine (HRMMU)1. It covers the period from 16 February to 15 May 2015. 2. The reporting period -

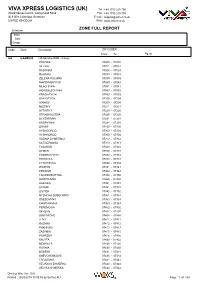

Viva Xpress Logistics (Uk)

VIVA XPRESS LOGISTICS (UK) Tel : +44 1753 210 700 World Xpress Centre, Galleymead Road Fax : +44 1753 210 709 SL3 0EN Colnbrook, Berkshire E-mail : [email protected] UNITED KINGDOM Web : www.vxlnet.co.uk Selection ZONE FULL REPORT Filter : Sort : Group : Code Zone Description ZIP CODES From To Agent UA UAAOD00 UA-Ukraine AOD - 4 days POLISKE 07000 - 07004 VILCHA 07011 - 07012 RADYNKA 07024 - 07024 RAHIVKA 07033 - 07033 ZELENA POLIANA 07035 - 07035 MAKSYMOVYCHI 07040 - 07040 MLACHIVKA 07041 - 07041 HORODESCHYNA 07053 - 07053 KRASIATYCHI 07053 - 07053 SLAVUTYCH 07100 - 07199 IVANKIV 07200 - 07204 MUSIIKY 07211 - 07211 DYTIATKY 07220 - 07220 STRAKHOLISSIA 07225 - 07225 OLYZARIVKA 07231 - 07231 KROPYVNIA 07234 - 07234 ORANE 07250 - 07250 VYSHGOROD 07300 - 07304 VYSHHOROD 07300 - 07304 RUDNIA DYMERSKA 07312 - 07312 KATIUZHANKA 07313 - 07313 TOLOKUN 07323 - 07323 DYMER 07330 - 07331 KOZAROVYCHI 07332 - 07332 HLIBOVKA 07333 - 07333 LYTVYNIVKA 07334 - 07334 ZHUKYN 07341 - 07341 PIRNOVE 07342 - 07342 TARASIVSCHYNA 07350 - 07350 HAVRYLIVKA 07350 - 07350 RAKIVKA 07351 - 07351 SYNIAK 07351 - 07351 LIUTIZH 07352 - 07352 NYZHCHA DUBECHNIA 07361 - 07361 OSESCHYNA 07363 - 07363 KHOTIANIVKA 07363 - 07363 PEREMOGA 07402 - 07402 SKYBYN 07407 - 07407 DIMYTROVE 07408 - 07408 LITKY 07411 - 07411 ROZHNY 07412 - 07412 PUKHIVKA 07413 - 07413 ZAZYMIA 07415 - 07415 POHREBY 07416 - 07416 KALYTA 07420 - 07422 MOKRETS 07425 - 07425 RUDNIA 07430 - 07430 BOBRYK 07431 - 07431 SHEVCHENKOVE 07434 - 07434 TARASIVKA 07441 - 07441 VELIKAYA DYMERKA 07442 - 07442 VELYKA -

Report on the Human Rights Situation in Ukraine 16 May to 15 August 2017

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Report on the human rights situation in Ukraine 16 May to 15 August 2017 Contents Paragraphs Page I. Executive summary ................................................................................................. 1–21 1 II. Violations of the rights to life, liberty, security and physical integrity ................... 22–68 4 A. International humanitarian law in the conduct of hostilities ........................... 22–31 4 B. Civilian casualties ........................................................................................... 32–36 6 C. Missing persons and recovery of human remains ........................................... 37–38 8 D. Summary executions, deprivation of liberty, enforced disappearances, torture and ill-treatment, and conflict-related sexual violence ................................ 39–68 8 1. Summary executions and killings ....................................................... 39–42 8 2. Unlawful/arbitrary deprivation of liberty, enforced disappearances and abductions ....................................................................................... 43–51 9 3. Torture and ill-treatment .................................................................... 52–62 11 4. Conflict-related sexual violence ......................................................... 63–66 13 5. Exchanges of individuals deprived of liberty ..................................... 67 14 6. Transfer of pre-conflict prisoners to government-controlled territory 68 14 III. -

Report on the Human Rights Situation in Ukraine 16 August to 15

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Report on the human rights situation in Ukraine 16 August to 15 November 2017 Contents Paragraphs Page I. Executive summary ................................................................................................. 1–19 1 II. Rights to life, liberty, security and physical integrity ............................................. 20–66 4 A. International humanitarian law in the conduct of hostilities ........................... 20–25 4 B. Civilian casualties ........................................................................................... 26–30 6 C. Missing persons and recovery of human remains ........................................... 31–33 9 D. Summary executions, killings, deprivation of liberty, enforced disappearances, torture and ill-treatment, and conflict-related sexual violence ........................ 34–66 9 1. Summary executions and killings ....................................................... 34–35 9 2. Unlawful/arbitrary deprivation of liberty, enforced disappearances and abductions .................................................................................. 36–46 10 3. Torture and ill-treatment .................................................................... 47–54 12 4. Conflict-related sexual violence ......................................................... 55–58 14 5. Access to places of detention .............................................................. 59–60 15 6. Conditions of detention ...................................................................... -

Report on the Human Rights Situation in Ukraine 16 August to 15 November 2017

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Report on the human rights situation in Ukraine 16 August to 15 November 2017 Contents Paragraphs Page I. Executive summary ................................................................................................. 1–19 1 II. Rights to life, liberty, security and physical integrity ............................................. 20–66 4 A. International humanitarian law in the conduct of hostilities ........................... 20–25 4 B. Civilian casualties ........................................................................................... 26–30 6 C. Missing persons and recovery of human remains ........................................... 31–33 9 D. Summary executions, killings, deprivation of liberty, enforced disappearances, torture and ill-treatment, and conflict-related sexual violence ........................ 34–66 9 1. Summary executions and killings ....................................................... 34–35 9 2. Unlawful/arbitrary deprivation of liberty, enforced disappearances and abductions .................................................................................. 36–46 10 3. Torture and ill-treatment .................................................................... 47–54 12 4. Conflict-related sexual violence ......................................................... 55–58 14 5. Access to places of detention .............................................................. 59–60 15 6. Conditions of detention ......................................................................