Imperfectly Camouflaged Avian Eggs: Artefact Or Adaptation?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sericornis, Acanthizidae)

GENETIC AND MORPHOLOGICAL DIFFERENTIATION AND PHYLOGENY IN THE AUSTRALO-PAPUAN SCRUBWRENS (SERICORNIS, ACANTHIZIDAE) LESLIE CHRISTIDIS,1'2 RICHARD $CHODDE,l AND PETER R. BAVERSTOCK 3 •Divisionof Wildlifeand Ecology, CSIRO, P.O. Box84, Lyneham,Australian Capital Territory 2605, Australia, 2Departmentof EvolutionaryBiology, Research School of BiologicalSciences, AustralianNational University, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory 2601, Australia, and 3EvolutionaryBiology Unit, SouthAustralian Museum, North Terrace, Adelaide, South Australia 5000, Australia ASS•CRACr.--Theinterrelationships of 13 of the 14 speciescurrently recognized in the Australo-Papuan oscinine scrubwrens, Sericornis,were assessedby protein electrophoresis, screening44 presumptivelo.ci. Consensus among analysesindicated that Sericorniscomprises two primary lineagesof hithertounassociated species: S. beccarii with S.magnirostris, S.nouhuysi and the S. perspicillatusgroup; and S. papuensisand S. keriwith S. spiloderaand the S. frontalis group. Both lineages are shared by Australia and New Guinea. Patternsof latitudinal and altitudinal allopatry and sequencesof introgressiveintergradation are concordantwith these groupings,but many featuresof external morphologyare not. Apparent homologiesin face, wing and tail markings, used formerly as the principal criteria for grouping species,are particularly at variance and are interpreted either as coinherited ancestraltraits or homo- plasies. Distribution patternssuggest that both primary lineageswere first split vicariantly between -

The Effect of Intense Light on Bird Behavior and Physiology

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Wildlife Damage Management, Internet Center Bird Control Seminars Proceedings for October 1973 THE EFFECT OF INTENSE LIGHT ON BIRD BEHAVIOR AND PHYSIOLOGY Sheldon Lustick Ohio State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdmbirdcontrol Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Lustick, Sheldon, "THE EFFECT OF INTENSE LIGHT ON BIRD BEHAVIOR AND PHYSIOLOGY" (1973). Bird Control Seminars Proceedings. 119. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdmbirdcontrol/119 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Wildlife Damage Management, Internet Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bird Control Seminars Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 171 THE EFFECT OF INTENSE LIGHT ON BIRD BEHAVIOR AND PHYSIOLOGY Sheldon Lustick Zoology Department Ohio State University , Columbus , Ohio 43210 It has been known for centuries that light (photoperiod ) is possibly the major environmental stimuli affecting bird behavior and physiology. The length of the light period stimulates the breeding cycle , migration , fat de - position , and molt in most species of birds. Therefore , it is only natural that one would think of using light as a means of bird control. In fa ct , light has already been used as a bird control; flood -light traps have been used to trap blackbirds (Meanley 1971 ); Meanley states that 2000 -W search lights have been used to alleviate depredation by ducks in rice fields. -

Magnificent Magpie Colours by Feathers with Layers of Hollow Melanosomes Doekele G

© 2018. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2018) 221, jeb174656. doi:10.1242/jeb.174656 RESEARCH ARTICLE Magnificent magpie colours by feathers with layers of hollow melanosomes Doekele G. Stavenga1,*, Hein L. Leertouwer1 and Bodo D. Wilts2 ABSTRACT absorption coefficient throughout the visible wavelength range, The blue secondary and purple-to-green tail feathers of magpies are resulting in a higher refractive index (RI) than that of the structurally coloured owing to stacks of hollow, air-containing surrounding keratin. By arranging melanosomes in the feather melanosomes embedded in the keratin matrix of the barbules. barbules in more or less regular patterns with nanosized dimensions, We investigated the spectral and spatial reflection characteristics of vivid iridescent colours are created due to constructive interference the feathers by applying (micro)spectrophotometry and imaging in a restricted wavelength range (Durrer, 1977; Prum, 2006). scatterometry. To interpret the spectral data, we performed optical The melanosomes come in many different shapes and forms, and modelling, applying the finite-difference time domain (FDTD) method their spatial arrangement is similarly diverse (Prum, 2006). This has as well as an effective media approach, treating the melanosome been shown in impressive detail by Durrer (1977), who performed stacks as multi-layers with effective refractive indices dependent on extensive transmission electron microscopy of the feather barbules the component media. The differently coloured magpie feathers are of numerous bird species. He interpreted the observed structural realised by adjusting the melanosome size, with the diameter of the colours to be created by regularly ordered melanosome stacks acting melanosomes as well as their hollowness being the most sensitive as optical multi-layers. -

European Red List of Birds

European Red List of Birds Compiled by BirdLife International Published by the European Commission. opinion whatsoever on the part of the European Commission or BirdLife International concerning the legal status of any country, Citation: Publications of the European Communities. Design and layout by: Imre Sebestyén jr. / UNITgraphics.com Printed by: Pannónia Nyomda Picture credits on cover page: Fratercula arctica to continue into the future. © Ondrej Pelánek All photographs used in this publication remain the property of the original copyright holder (see individual captions for details). Photographs should not be reproduced or used in other contexts without written permission from the copyright holder. Available from: to your questions about the European Union Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed Published by the European Commission. A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server (http://europa.eu). Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication. ISBN: 978-92-79-47450-7 DOI: 10.2779/975810 © European Union, 2015 Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Printed in Hungary. European Red List of Birds Consortium iii Table of contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................................1 Executive summary ...................................................................................................................................................5 1. -

Supplementary Material

Pterocles alchata (Pin-tailed Sandgrouse) European Red List of Birds Supplementary Material The European Union (EU27) Red List assessments were based principally on the official data reported by EU Member States to the European Commission under Article 12 of the Birds Directive in 2013-14. For the European Red List assessments, similar data were sourced from BirdLife Partners and other collaborating experts in other European countries and territories. For more information, see BirdLife International (2015). Contents Reported national population sizes and trends p. 2 Trend maps of reported national population data p. 3 Sources of reported national population data p. 5 Species factsheet bibliography p. 6 Recommended citation BirdLife International (2015) European Red List of Birds. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. Further information http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/info/euroredlist http://www.birdlife.org/europe-and-central-asia/european-red-list-birds-0 http://www.iucnredlist.org/initiatives/europe http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/conservation/species/redlist/ Data requests and feedback To request access to these data in electronic format, provide new information, correct any errors or provide feedback, please email [email protected]. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™ BirdLife International (2015) European Red List of Birds Pterocles alchata (Pin-tailed Sandgrouse) Table 1. Reported national breeding population size and trends in Europe1. Country (or Population estimate Short-term -

Transport of Water by Adult Sandgrouse to Their Young Tom J

THE CONDOR VOLUME69 JULY-AUGUST,1967 NUMBER4 TRANSPORT OF WATER BY ADULT SANDGROUSE TO THEIR YOUNG TOM J. CADE and GORDONL. MACLEAN In 1896 the English aviculturist Meade-Waldo published an astonishing and seemingly incredible account of how the males of sandgrouse that he successfully bred in captivity carried water to their young in their breast feathers. To quote from his original report: As soon as the young were out of the nest (when twelve hours old) a very curious habit developed itself in the male. He would rub his breast violently up and down on the ground, a motion quite distinct from dusting, and when all awry he would get into his drinking water and saturate the feathers of the under parts. When soaked he would go through the motions of flying away, nodding his head, etc. Then, remembering his family were close by, would run up to the hen, make a demonstration, when the young would run out, get under him, and suckthe water from his breast. This is no doubt the way that water is conveyed to the young when far out on waterless plains. The young . are very independent, eating hard seed and weeds from the first, and roosting independently of their parents at ten days old (Meade-Waldo, 1896). See also Meade- Waldo (1921). Despite the fact that .Meade-Waldo (1897 ; 1921) observed 61 broods from three different species of sandgrouse hatched in his aviaries between 189.5 and l915, and soon received confirmation from another breeder for two species (St. Quintin, 1905), and despite the fact that field naturalists and native hunters have frequently observed wild male sandgrouse wetting their breast feathers at water holes in the way described (Meade-Waldo, 1906; Buxton, 1923; Heim de Balsac, 1936; Hoesch, 1955), the idea that the young do receive water in this exceptional way has met with a great deal of scepticism (Archer and Godman, 1937; Meinertzhagen, 1954, 1964; Hiie and Etchkcopar, 1957; Schmidt-Nielsen, 1964). -

![A Report on the Guano-Producing Birds of Peru [“Informe Sobre Aves Guaneras”]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2754/a-report-on-the-guano-producing-birds-of-peru-informe-sobre-aves-guaneras-982754.webp)

A Report on the Guano-Producing Birds of Peru [“Informe Sobre Aves Guaneras”]

PACIFIC COOPERATIVE STUDIES UNIT UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI`I AT MĀNOA Dr. David C. Duffy, Unit Leader Department of Botany 3190 Maile Way, St. John #408 Honolulu, Hawai’i 96822 Technical Report 197 A report on the guano-producing birds of Peru [“Informe sobre Aves Guaneras”] July 2018* *Original manuscript completed1942 William Vogt1 with translation and notes by David Cameron Duffy2 1 Deceased Associate Director of the Division of Science and Education of the Office of the Coordinator in Inter-American Affairs. 2 Director, Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit, Department of Botany, University of Hawai‘i at Manoa Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96822, USA PCSU is a cooperative program between the University of Hawai`i and U.S. National Park Service, Cooperative Ecological Studies Unit. Organization Contact Information: Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit, Department of Botany, University of Hawai‘i at Manoa 3190 Maile Way, St. John 408, Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96822, USA Recommended Citation: Vogt, W. with translation and notes by D.C. Duffy. 2018. A report on the guano-producing birds of Peru. Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit Technical Report 197. University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Department of Botany. Honolulu, HI. 198 pages. Key words: El Niño, Peruvian Anchoveta (Engraulis ringens), Guanay Cormorant (Phalacrocorax bougainvillii), Peruvian Booby (Sula variegate), Peruvian Pelican (Pelecanus thagus), upwelling, bird ecology behavior nesting and breeding Place key words: Peru Translated from the surviving Spanish text: Vogt, W. 1942. Informe elevado a la Compañia Administradora del Guano par el ornitólogo americano, Señor William Vogt, a la terminación del contracto de tres años que con autorización del Supremo Gobierno celebrara con la Compañia, con el fin de que llevara a cabo estudios relativos a la mejor forma de protección de las aves guaneras y aumento de la produción de las aves guaneras. -

Temporal and Spatial Patterns of Abundance and Breeding Activity of Namaqua Sandgrouse in South Africa

162 S.-Afr.Tydskr.Dierk.1994.29(2) Temporal and spatial patterns of abundance and breeding activity of Namaqua sandgrouse in South Africa G. Malan, R.M. Little' and T.M. Crowe FitzPatrick I nstitute, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch, 7700 Republic of South Africa Received 15 Novemher 1993; accepted 25 January 1994 We examined various measures of temporal and spatial patterns of abundance and breeding activity of Namaqua sandgrouse Pterocles namaqua (presumably mostly for P. n. furvus) in South Africa. Bird-atlas maps indicating reporting-rates and extensive-counts showed that the majority of Namaqua sandgrouse concentrate in Bushmanland, in the north-western Cape Province, from December to March. From April to July the sandgrouse move north and east of Bushmanland and apparently return to Bushmanland from August to November. This west-east movement occurs at a relatively constant rate of 30-50 km per month. Only 15% of the sandgrouse ringed at an estate within the eastern part of this species range returned the following winter. Follicle diameter and brood'patch measurements increased significantly from July to August, at the time when the majority of birds leave the estate. Belly-soaking was more prevalent in early summer in Bushmanland than in any season in the east. South African populations of Namaqua sandgrouse are partial migrants which breed primarily in early summer (October - November) in Bushmanland. Temporale en ruimtelike patrone in verspreiding en broei aktiwiteite van die Namaqua sandpatrys Pterocles namaqua (vermoedelik meestal P. n. furvus) IS ondersoek in Suid Afrika. Die voelatlaskaarte wat rapporteer skale en ekstensiewe·tellings wys, het aangedui dat van Desember tot Maart die meerderheid sandpatryse gekonsentreer is in Boesmanland. -

Namibia & the Okavango

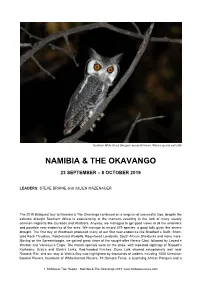

Southern White-faced Owl gave wonderful views. What a special owl! (JM) NAMIBIA & THE OKAVANGO 23 SEPTEMBER – 8 OCTOBER 2019 LEADERS: STEVE BRAINE and JULIEN MAZENAUER The 2019 Birdquest tour to Namibia & The Okavango continued on a long run of successful trips, despite the extreme drought Southern Africa is experiencing at the moment, resulting in the lack of many usually common migrants like Cuckoos and Warblers. Anyway, we managed to get good views at all the endemics and possible near-endemics of the area. We manage to record 379 species, a good tally given the severe drought. The first day at Windhoek produced many of our first near-endemics like Bradfield’s Swift, Short- toed Rock Thrushes, Violet-eared Waxbills, Rosy-faced Lovebirds, South African Shelducks and many more. Moving on the Spreetshoogte, we gained great views of the sought-after Herero Chat, followed by Layard’s Warbler and Verreaux’s Eagle. The Namib specials were on the show, with repeated sightings of Rüppell’s Korhaans, Gray’s and Stark’s Larks, Red-headed Finches. Dune Lark showed exceptionally well near Rostock Ritz, and our stay at Walvis Bay was highlighted by thousands of waders including 1500 Chestnut- banded Plovers, hundreds of White-fronted Plovers, 15 Damara Terns, a surprising African Penguin and a 1 BirdQuest Tour Report : Namibia & The Okavango 2019 www.birdquest-tours.com Northern Giant Petrel as write-in. Huab Lodge delighted us with its Rockrunners, Hartlaub’s Spurfowl, White- tailed Shrike, and amazing sighting of Southern White-faced Owl, African Scops Owl, Freckled Nightjar few feet away and our first White-tailed Shrikes and Violet Wood Hoopoes. -

Bird Dispersal Techniques Are a Vital Part of Safely and Droppings And, in Some Cases, Their Aggressive Behavior Efficiently Reducing Bird Conflicts with Humans

U.S. Department of Agriculture Animal & Plant Health Inspection Service Wildlife Services August 2016 Bird Dispersal Wildlife Damage Management Technical Series Techniques Thomas W. Seamans Supervisory Wildlife Biologist USDA-APHIS-Wildlife Services National Wildlife Research Center Sandusky, Ohio Allen Gosser State Director USDA-APHIS-Wildlife Services Rensselaer, New York Figure 1. Photo of a frightened wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo). Human-Wildlife Conflicts Quick Links Conflicts between humans and birds likely Successful dispersal techniques should have existed since agricultural practices capitalize on bird sensory capabilities. If Human-Wildlife Conflicts 1 began. Paintings from ancient Greek, birds cannot perceive the dispersal Habitat Modification 2 Egyptian, and Roman civilizations depict technique, it will not be effective in Frightening Techniques 4 birds attacking crops. In Great Britain, dispersing birds. recording of efforts at reducing bird Bird Management 7 damage began in the 1400s, with books Birds rely primarily on their vision and Examples on bird control written in the 1600s. Even hearing to find food, avoid predators, and Conclusion 8 so, the problem persists. Avian damage to locate mates. Bird vision is quite different crops remains an issue today, but we also from human vision; birds can see colors Glossary & Key Words 10 are concerned with damage to homes, that humans cannot perceive (including Resources 11 businesses, and aircraft, and the the ultraviolet range), and and they detect possibility of disease transmission from and use polarized light. Bird response to birds to humans or livestock. scare devices (Figure 1) that rely on vision Page 2 WDM Technical Series—Bird Dispersal may depend on the visibility of the object to the bird, as present. -

An Initial Estimate of Avian Ark Kinds

Answers Research Journal 6 (2013):409–466. www.answersingenesis.org/arj/v6/avian-ark-kinds.pdf An Initial Estimate of Avian Ark Kinds Jean K. Lightner, Liberty University, 1971 University Blvd, Lynchburg, Virginia, 24515. Abstract Creationists recognize that animals were created according to their kinds, but there has been no comprehensive list of what those kinds are. As part of the Answers in Genesis Ark Encounter project, research was initiated in an attempt to more clearly identify and enumerate vertebrate kinds that were SUHVHQWRQWKH$UN,QWKLVSDSHUXVLQJPHWKRGVSUHYLRXVO\GHVFULEHGSXWDWLYHELUGNLQGVDUHLGHQWLÀHG 'XHWRWKHOLPLWHGLQIRUPDWLRQDYDLODEOHDQGWKHIDFWWKDWDYLDQWD[RQRPLFFODVVLÀFDWLRQVVKLIWWKLVVKRXOG be considered only a rough estimate. Keywords: Ark, kinds, created kinds, baraminology, birds Introduction As in mammals and amphibians, the state of avian $VSDUWRIWKH$UN(QFRXQWHUSURMHFW$QVZHUVLQ WD[RQRP\LVLQÁX['HVSLWHWKHLGHDORIQHDWO\QHVWHG Genesis initiated and funded research in an attempt hierarchies in taxonomy, it seems groups of birds to more clearly identify and enumerate the vertebrate are repeatedly “changing nests.” This is partially NLQGVWKDWZHUHSUHVHQWRQWKH$UN,QDQLQLWLDOSDSHU because where an animal is placed depends on which WKH FRQFHSW RI ELEOLFDO NLQGV ZDV GLVFXVVHG DQG D characteristics one chooses to consider. While many strategy to identify them was outlined (Lightner et al. had thought that molecular data would resolve these 6RPHRIWKHNH\SRLQWVDUHQRWHGEHORZ issues, in some cases it has exacerbated them. For this There is tremendous variety seen today in animal HVWLPDWHRIWKHDYLDQ$UNNLQGVWKHWD[RQRPLFVFKHPH OLIHDVFUHDWXUHVKDYHPXOWLSOLHGDQGÀOOHGWKHHDUWK presented online by the International Ornithologists’ since the Flood (Genesis 8:17). In order to identify 8QLRQ ,28 ZDVXVHG *LOODQG'RQVNHUD which modern species are related, being descendants 2012b and 2013). This list includes information on RI D VLQJOH NLQG LQWHUVSHFLÀF K\EULG GDWD LV XWLOL]HG extant and some recently extinct species. -

The Dulmison BFD Is Available in a Variety of Colors and Different Sizes to Accommodate Wires Ranging from 0.175 to 1.212 Inches (Figure 4-9)

The Dulmison BFD is available in a variety of colors and different sizes to accommodate wires ranging from 0.175 to 1.212 inches (Figure 4-9). The BFD has been effective when tested on transmission overhead static wires in Europe, where typical spacing ranges &om 16 to 33 feet. In North America, the BFD also has shown to be effective in reducing waterfowl collisions with overhead static wires (Crowder 2000). The BFD is believed to be effective because its profile increases line visibility. As with “active devices” such as the Flapper, these more “passive” devices have not been tested on communication tower guy wires; however, it is assumed that they would Figure 4-9 Bird Flight Diverters for Small and Larger increase the profile and, therefore, the Wires visibility of the guy wires during daytime conditions. Regarding long-term use, BFD colors may fade after long periods of exposure but should not become brittle or lose their elastic properties. ESKOM has used the Preformed Line Products, BFD in South Atka for years with no reports of mechanical failure (van Rooyen 2000) although some red PVC devices have faded. 4.2.1.4 Swan Flight Diverter The Swan Flight Diverter (SFD) is similar to the BFD but includes four 7-inch spirals (Figure 4-10). The SFD also is made from a high-impact, standard gray PVC and is UV stabilized. The Dulmison SFD is available in a variety of colors and sizes to accommodate wires ranging fiom 0.175 to 1.212 inches. Notice Of Inquiry Comment Review 4-14 September 2004 Final Figure 4-10 Swan Flight Diverters Being Placed on a Static Wire As with the BFD, the SFD has been shown to be effective when installed on transmission overhead static wires in North America, but has not been tested on tower guy wires.