JOURNAL of ADVENTIST ARCHIVES Volume 1 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origins of Millerite Separatism

The Origins of Millerite Separatism By Andrew Taylor (BA in History, Aurora University and MA in History, University of Rhode Island) CHAPTER 1 HISTORIANS AND MILLERITE SEPARATISM ===================================== Early in 1841, Truman Hendryx moved to Bradford, Pennsylvania, where he quickly grew alienated from his local church. Upon settling down in his new home, Hendryx attended several services in his new community’s Baptist church. After only a handful of visits, though, he became convinced that the church did not believe in what he referred to as “Bible religion.” Its “impiety” led him to lament, “I sometimes almost feel to use the language [of] the Prophecy ‘Lord, they have killed thy prophets and digged [sic] down thine [sic] altars and I only am left alone and they seek my life.”’1 His opposition to the church left him isolated in his community, but his fear of “degeneracy in the churches and ministers” was greater than his loneliness. Self-righteously believing that his beliefs were the “Bible truth,” he resolved to remain apart from the Baptist church rather than attend and be corrupted by its “sinful” influence.2 The “sinful” church from which Hendryx separated himself was characteristic of mainstream antebellum evangelicalism. The tumultuous first decades of the nineteenth century had transformed the theological and institutional foundations of mainstream American Protestantism. During the colonial era, American Protestantism had been dominated by the Congregational, Presbyterian, and Anglican churches, which, for the most part, had remained committed to the theology of John Calvin. In Calvinism, God was envisioned as all-powerful, having predetermined both the course of history and the eternal destiny of all humans. -

Lest We Forget | 4

© 2021 ADVENTIST PIONEER LIBRARY P.O. Box 51264 Eugene, OR, 97405, USA www.APLib.org Published in the USA February, 2021 ISBN: 978-1-61455-103-4 Lest We ForgetW Inspiring Pioneer Stories Adventist Pioneer Library 4 | Lest We Forget Endorsements and Recommendations Kenneth Wood, (former) President, Ellen G. White Estate —Because “remembering” is es- sential to the Seventh-day Adventist Church, the words and works of the Adventist pioneers need to be given prominence. We are pleased with the skillful, professional efforts put forth to accom- plish this by the Pioneer Library officers and staff. Through books, periodicals and CD-ROM, the messages of the pioneers are being heard, and their influence felt. We trust that the work of the Adventist Pioneer Library will increase and strengthen as earth’s final crisis approaches. C. Mervyn Maxwell, (former) Professor of Church History, SDA Theological Semi- nary —I certainly appreciate the remarkable contribution you are making to Adventist stud- ies, and I hope you are reaching a wide market.... Please do keep up the good work, and may God prosper you. James R. Nix, (former) Vice Director, Ellen G. White Estate —The service that you and the others associated with the Adventist Pioneer Library project are providing our church is incalculable To think about so many of the early publications of our pioneers being available on one small disc would have been unthinkable just a few years ago. I spent years collecting shelves full of books in the Heritage Room at Loma Linda University just to equal what is on this one CD-ROM. -

Origin and History of Seventh-Day Adventists, Vol. 1

Origin and History of Seventh-day Adventists FRONTISPIECE PAINTING BY HARRY ANDERSON © 1949, BY REVIEW AND HERALD As the disciples watched their Master slowly disappear into heaven, they were solemnly reminded of His promise to come again, and of His commission to herald this good news to all the world. Origin and History of Seventh-day Adventists VOLUME ONE by Arthur Whitefield Spalding REVIEW AND HERALD PUBLISHING ASSOCIATION WASHINGTON, D.C. COPYRIGHT © 1961 BY THE REVIEW AND HERALD PUBLISHING ASSOCIATION WASHINGTON, D.C. OFFSET IN THE U.S.A. AUTHOR'S FOREWORD TO FIRST EDITION THIS history, frankly, is written for "believers." The reader is assumed to have not only an interest but a communion. A writer on the history of any cause or group should have suffi- cient objectivity to relate his subject to its environment with- out distortion; but if he is to give life to it, he must be a con- frere. The general public, standing afar off, may desire more detachment in its author; but if it gets this, it gets it at the expense of vision, warmth, and life. There can be, indeed, no absolute objectivity in an expository historian. The painter and interpreter of any great movement must be in sympathy with the spirit and aim of that movement; it must be his cause. What he loses in equipoise he gains in momentum, and bal- ance is more a matter of drive than of teetering. This history of Seventh-day Adventists is written by one who is an Adventist, who believes in the message and mission of Adventists, and who would have everyone to be an Advent- ist. -

A Canonical Reading of Hebrews 3:7-4:13" (David E. Garland)

BOOKREVIEWS 28 1 Promise of Rest: A Canonical Reading of Hebrews 3:7-4:13" (David E. Garland). Dockery affirms a sound typological interpretation. Citing texts from John 5:39- 40 and John 5:46, he demonstrates how Jesus understood the OT as referring to himself and saw himself as the antitype of individuals like David, Solomon, Elijah, and others (162-163). While parts 1 and 2 are primarily concerned with methodological issues, part 3 (225-315) concentrates on practical ways of applying the OT to modern culture and the church. In "Preaching the Present Tense: Coming Alive to the Old Testament," Al Fasol focuses on the important homiletical issues involved in preaching the OT. He recommends that the theme text of the sermon be summarized with a brief, interpretive, past-tense statement. This sentence should reflect the Eternal Truth of the Text (E.T.T.). This is to be followed by a present-tense sentence of application which communicates the Truth for Today (T.T.). While Klein offers this suggestion with the intent of making the text applicable, it seems to be a reflection of Stendahl's much-debated dichotomy between "what it meant" and "what it meansn-a dichotomy that has been challenged in some recent discussions. The chapters on "Changing the Church with the Words of God" (C. Richard Wells); "Changing Culture with Words from Godn (James Emery White); and "Where Do We Go from Here?: Integrating the Old Testament into Your Ministry" (Kenneth S. Hempell) represent a clear attempt to relate the OT to church and society. -

Download PDF 1.11 MB

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 Aliens in the World: Sectarians, Secularism and the Second Great Awakening Matt McCook Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ALIENS IN THE WORLD: SECTARIANS, SECULARISM AND THE SECOND GREAT AWAKENING By MATT MCCOOK A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2005 The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Matt McCook defended on August 18, 2005. ______________________________ Neil Jumonville Professor Directing Dissertation ______________________________ Thomas Joiner Outside Committee Member ______________________________ Elna Green Committee Member ______________________________ Albrecht Koschnik Committee Member ______________________________ Amanda Porterfield Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii The following is dedicated to three individuals whose lives have been and will be affected by this project and its completion as much as mine. One has supported me in every possible way throughout my educational pursuits, sharing the highs, the lows, the sacrifices, the frustration, but always being patient with me and believing in me more than I believed in myself. The second has inspired me to go back to the office to work many late nights while at the same time being the most welcome distraction constantly reminding me of what I value most. And the anticipated arrival of the third has inspired me to finish so that this precious child would not have to share his or her father with a dissertation. -

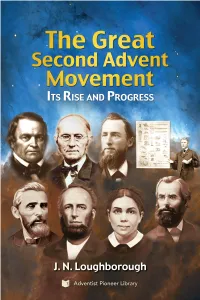

The Great Second Advent Movement.Pdf

© 2016 Adventist Pioneer Library 37457 Jasper Lowell Rd Jasper, OR, 97438, USA +1 (877) 585-1111 www.APLib.org Originally published by the Southern Publishing Association in 1905 Copyright transferred to Review and Herald Publishing Association Washington, D. C., Jan. 28, 1909 Copyright 1992, Adventist Pioneer Library Footnote references are assumed to be for those publications used in the 1905 edition of The Great Second Advent Movement. A few references have been updated to correspond with reprinted versions of certain books. They are as follows:— Early Writings, reprinted in 1945. Life Sketches, reprinted in 1943. Spiritual Gifts, reprinted in 1945. Testimonies for the Church, reprinted in 1948. The Desire of Ages, reprinted in 1940. The Great Controversy, reprinted in 1950. Supplement to Experience and Views, 1854. When this 1905 edition was republished in 1992 an additional Preface was added, as well as three appendices. It should be noted that Appendix A is a Loughborough document that was never published in his lifetime, but which defended the accuracy of the history contained herein. As noted below, the footnote references have been updated to more recent reprints of those referenced books. Otherwise, Loughborough’s original content is intact. Paging of the 1905 and 1992 editions are inserted in brackets. August, 2016 ISBN: 978-1-61455-032-7 4 | The Great Second Advent Movement J. N. LOUGHBOROUGH (1832-1924) Contents Preface 7 Preface to the 1992 Edition 9 Illustrations 17 Chapter 1 — Introductory 19 Chapter 2 — The Plan of Salvation -

Adventist Heritage Loma Linda University Publications

Loma Linda University TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works Adventist Heritage Loma Linda University Publications Spring 1995 Adventist Heritage - Vol. 16, No. 3 Adventist Heritage, Inc. Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/advent-heritage Part of the History Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Adventist Heritage, Inc., "Adventist Heritage - Vol. 16, No. 3" (1995). Adventist Heritage. http://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/advent-heritage/33 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by the Loma Linda University Publications at TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Adventist Heritage by an authorized administrator of TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 4 8 D • D THI: TWENTY- THREE. HUNDRED DAYI. B.C.457 3 \1• ~ 3 \11 14 THE ONE W lEEK. A ~~~@ ~im~ J~ ~~ ~& ~ a ~ill ' viS IONS ~ or DANIEL 6 J8HN. Sf.YOITU·D AY ADVENTIST PU BUSKIN ' ASSOCIATIO N. ~ATTIJ: CRHK. MlCJ{!GAfl. Editor-in-Chief Ronald D. Graybill La Sierra Unit•ersi ty Associate Editor Dorothy Minchin-Comm La ierra Unit•er ity Gary Land Andrews University Managing Editor Gary Chartier La Sierra University Volume 16, Number 3 Spring 1995 Letters to the Editor 2 The Editor's Stump 3 Gary Chartier Experience 4 The Millerite Experience: Charles Teel, ]r. Shared Symbols Informing Timely Riddles? Sanctuary 9 The Journey of an Idea Fritz Guy Reason 14 "A Feast of Reason" Anne Freed The Appeal of William Miller's Way of Reading the Bible Obituary 22 William Miller: An Obituary Evaluation of a Life Frederick G. -

A BRIEF BIOGRAPHY of CHARLES FITCH. Next in Our First of Ministers

A BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF CHARLES FITCH. Next in our first of ministers, that became closely associated with the Millerite movement is Charles Fitch who lived from 1805--October 14, 1844. He was born in Hampton, Connecticut. After graduating from Brown University, Fitch was ordained to the Congregational ministry and served at Abington, Connecticut, Warren, Massachusetts, and Hartford, Connecticut, successively. In 1836 he went to the Marlboro Congregational Chapel in Boston, and later to Newark, New Jersey, and Haverhill, Massachusetts. Fitch's greatest contribution was made at Cleveland, Ohio, after he became the western proponent of the advent message. His other interests included his membership in the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. p. 1, Para. 1, [BIOG]. He was a strong opponent to slavery as revealed by a pamphlet he produced entitled, Slaveholding Weighed in the Balance of Truth, and Its Comparative Guilt Illustrated. In it he stated, "Every man has a tongue, and he can use it; he has influence, and he can exert it; he has moral power, and he can put it forth. Up my friends and do your duty, to deliver the spoils out of the hands of the oppressor, lest the fire of God's fury kindle ere long upon you." The Prophetic Faith of Our Fathers, 534. p. 1, Para. 2, [BIOG]. In 1838, while he was pastor of the Marlboro Street Congregational Church in Boston, he was given a copy of Miller's Lectures, containing his views on the Second Advent. Fitch wrote to Miller, in March, confessing his "overwhelming interest such as I never felt in any other book except the Bible." Ibid. -

YRE 05 Denominational History

International Institute of Christian Ministries General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists Course in Denominational History (YRE 105) Written by Theodore N. Levterov Date: July, 2003 Table of Contents Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................... 3 Part One: Syllabus................................................................................................................................... 4 Part Two: Course Outline........................................................................................................................ 5 Bibliography......................................................................................................................... 53 2 Abbreviations AH Advent Herald A&D Wm.. Miller’s Apology and Defense, August 1 GCB General Conference Bulletin EW Early Writings MC Midnight Cry RH Review and Herald SG Spiritual Gifts T Testimonies for the Church (9 vols.) WLF A World to the “Little Flock” 3 Part One: Denominational History (YRE 105) Syllabus I. Course Objectives: A. To examine the stages in the development of the Seventh-day Adventist Church organization, doctrines, life- style, institutions, and mission. B. To show the relevance of Seventh-day Adventist history to contemporary issues in the church. C. To facilitate the integration of course content with the student’s personal faith, belief system, and life experience. II. Textbook: Schwarz, R. W, and Floyd Greenleaf. Light Bearers: A History of the Seventh-day -

The Original Three Advent Messages!

PAGE 1 THE ORIGINAL THREE ADVENT MESSAGES! THE FIRST ANGEL’S MESSAGE “THE JUDGMENT HOUR CRY” EXAMINED! STUDY DOCUMENT NO. 1 IN THIS FOUR PART SERIES. TRACING THE TEACHINGS OF EACH OF THESE MESSAGES FROM THE PENS OF THOSE WHO HAD AN ACTUAL EXPERIENCE IN THESE MESSAGES. PAGE 2 THE FIRST ANGEL’S MESSAGE - “THE JUDGMENT HOUR CRY” EXAMINED! TABLE OF CONTENTS: - THE SOURCE DOCUMENTS ENCLOSED: - SECTION 1 - INTRODUCTORY ARTICLES RELATING TO THE SECOND ADVENT MOVEMENT: - “WE ARE THE ADVENTISTS,” – THE ADVENT REVIEW, AND SABBATH HERALD, APRIL 18, 1854 – JAMES WHITE. “THE CRISIS HAS COME!” – THE SIGNS OF THE TIMES, AND EXPOSITOR OF PROPHECY, AUGUST 3, 1842 – BY J. V. HIMES. SECTION 2 - BOOKS AND TRACTS FROM VARIOUS SECOND ADVENTIST PREACHERS:- “SYNOPSIS OF MILLER’S VIEWS.” – BY WILLIAM MILLER – PRINTED IN 1843. “THE SECOND ADVENT MANUAL.” – BY APOLLOS HALE – 1843. “FIRST PRINCIPLES OF THE SECOND ADVENT FAITH.” – THE WESTERN MIDNIGHT CRY, APRIL 27, 1844 – BY L. D. FLEMING. “THE GREAT CRISIS. EIGHTEEN HUNDRED FORTY-THREE.” – THE SIGNS OF THE TIMES, AND EXPOSITOR OF PROPHECY, SEPTEMBER 7, 1842 – BY JOSIAH LITCH. “JUDAISM OVERTHROWN: OR, THE KINGDOM RESTORED TO THE TRUE ISRAEL. WITH THE SCRIPTURE EVIDENCE OF THE EPOCH OF THE KINGDOM IN 1843.” – BY JOSIAH LITCH – 1843. “A SOLEMN APPEAL TO MINISTERS AND CHURCHES, ESPECIALLY TO THOSE OF THE BAPTIST DENOMINATION, RELATIVE TO THE SPEEDY COMING OF CHRIST.” – BY J. B. COOK – 1843. “THE KINGDOM OF GOD.” – BY WILLIAM MILLER – 1842. “VIEWS AND EXPERIENCE IN RELATION TO ENTIRE CONSECRATION AND THE SECOND ADVENT. ADDRESSED TO THE MINISTERS OF THE PORTSMOUTH, N. -

Light Bearers to the Remnant

Light BearersAR qf to the Remnant Light Bearers to the Remnant Denominational History Textbook for Seventh-day Adventist College Classes by R. W. Schwarz Prepared by the Depai iment of Education General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists PACIFIC PRESS PUBLISHING ASSOCIATION Mountain. View, California Omaha, Nebraska Oshawa, Ontario 1919 Copyright © 1979 by Pacific Press Publishing Association Litho in United States of America All Rights Reserved Design by Ichiro Nakashima Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 78-70730 FOREWORD Seventh-day Adventists must never forget the precious heritage that is ours. The message we refer to affectionately as the "Three Angels' Mes- sages," or simply as "the truth," has come to us as a legacy of long hours and days of prayer and study by men and women of God. The organization of our church is not the result of happenstance—God used men and women of commitment and ability to design the church structure that has served so effectively through the years. Light bearers these men and women were, indeed. They were God-led, God-blessed light bearers— light bearers who bore the torch gloriously through the years. We pause a moment to honor their memory—to pay tribute to all who were used of God to accomplish so much for the cause of present truth. The Seventh-day Adventist Church is not in the world today only as another ecclesiastical organization. The advent movement was heaven- born. It has been heaven-blessed through the decades of its existence and, thank God, it is heaven-bound. The message that has made us a people is a Christ-centered, Bible-based message. -

Knight, George R., Comp. and Ed. 1844 and the Rise of Sabbatarian Adventism

BOOK REVIEWS 283 of Millerism (266). Two of these groups-the Advent Christians and Seventh-day Adventists-are the focus of chapters 13 and 14. Millennia1 Fever could have been improved in three ways. First, a comprehensive text deserves more than eight pages of photographs to cover the movement adequately. Second, the book lacks a bibliography to organize the 33 pages of endnotes. Finally, the ties between Millerism and Shakerism (257- 263) are more amply explored than is the bridge between Millerism and spiritualism (245-247, 284), opening perhaps another door for future research. Nonetheless, this is still the best extant survey of Millerism. Andrews University BRIANE. STRAYER Knight, George R., comp. and ed. 1844 and the Rise of Sabbatarian Adventism. Hagerstown, MD: Review and Herald Pub., 1994. 190 pp. $14.95. George Knight's 1844 and the Rise of Sabbatarian Adventism is not a narrative history, but rather an anthology of primary source materials of Millerite Adventism and early Sabbatarian Adventism. From thousands of source documents preserved in four major archives-the Jencks Memorial Collection of Adventual Materials at Aurora University, the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Adventist Heritage Center at Andrews University, and the Ellen G. White Estate in Silver Spring, Maryland-Knight has selected 33 exhibits of which the "majority have never been republished in any form" since their origination (8). They range in length from short personal letters to a 48- page article on "The Rise and Progress of Adventism" from the Advent Shield and Review of May 1844. The selections span a broad spectrum of topics: historical overview, biographies and autobiographies, theological and doctrinal exposition, and letters.