Earthquake in the Vatican Media. the Winter Campaign of Bergoglio's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L'o S S E Rvator E Romano

Price € 1,00. Back issues € 2,00 L’O S S E RVATOR E ROMANO WEEKLY EDITION IN ENGLISH Unicuique suum Non praevalebunt Fifty-third year, number 19 (2.646) Vatican City Friday, 8 May 2020 Higher Committee of Human Fraternity calls to join together on 14 May A day of prayer, fasting and works of charity The Holy Father has accepted the proposal of the Higher Commit- tee of Human Fraternity to call for a day of prayer, of fasting and works of charity on Thursday, 14 May, to be observed by all men and women “believers in God, the All-Creator”. The proposal is addressed to all religious leaders and to people around the world to implore God to help humanity overcome the coronavirus (Covid- 19) pandemic. The appeal released on Sat- urday, 2 May, reads: “Our world is facing a great danger that threatens the lives of millions of people around the world due to the growing spread of the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic. While we reaffirm the role of medicine and scientific research in fighting this pandemic, we should not forget to seek refuge in God, the All-Creator, as we face such severe crisis. Therefore, we call on all peoples around the world to do good deeds, observe fast, pray, and make devout sup- plications to God Almighty to end this pandemic. Each one from wherever they are and ac- cording to the teachings of their religion, faith, or sect, should im- plore God to lift this pandemic off us and the entire world, to rescue us all from this adversity, to inspire scientists to find a cure that can turn back this disease, and to save the whole world from the health, economic, and human repercussions of this serious pan- demic. -

Newsletter 2020 I

NEWSLETTER EMBASSY OF MALAYSIA TO THE HOLY SEE JAN - JUN 2020 | 1ST ISSUE 2020 INSIDE THIS ISSUE • Message from His Excellency Westmoreland Palon • Traditional Exchange of New Year Greetings between the Holy Father and the Diplomatic Corp • Malaysia's contribution towards Albania's recovery efforts following the devastating earthquake in November 2019 • Meeting with Archbishop Ian Ernest, the Archbishop of Canterbury's new Personal Representative to the Holy See & Director of the Anglican Centre in Rome • Visit by Secretary General of the Ministry of Water, Land and Natural Resources • A Very Warm Welcome to Father George Harrison • Responding to COVID-19 • Pope Called for Joint Prayer to End the Coronavirus • Malaysia’s Diplomatic Equipment Stockpile (MDES) • Repatriation of Malaysian Citizens and their dependents from the Holy See and Italy to Malaysia • A Fond Farewell to Mr Mohd Shaifuddin bin Daud and family • Selamat Hari Raya Aidilfitri & Selamat Hari Gawai • Post-Lockdown Gathering with Malaysians at the Holy See Malawakil Holy See 1 Message From His Excellency St. Peter’s Square, once deserted, is slowly coming back to life now that Italy is Westmoreland Palon welcoming visitors from neighbouring countries. t gives me great pleasure to present you the latest edition of the Embassy’s Nonetheless, we still need to be cautious. If Inewsletter for the first half of 2020. It has we all continue to do our part to help flatten certainly been a very challenging year so far the curve and stop the spread of the virus, for everyone. The coronavirus pandemic has we can look forward to a safer and brighter put a halt to many activities with second half of the year. -

The Holy See (Including Vatican City State)

COMMITTEE OF EXPERTS ON THE EVALUATION OF ANTI-MONEY LAUNDERING MEASURES AND THE FINANCING OF TERRORISM (MONEYVAL) MONEYVAL(2012)17 Mutual Evaluation Report Anti-Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of Terrorism THE HOLY SEE (INCLUDING VATICAN CITY STATE) 4 July 2012 The Holy See (including Vatican City State) is evaluated by MONEYVAL pursuant to Resolution CM/Res(2011)5 of the Committee of Ministers of 6 April 2011. This evaluation was conducted by MONEYVAL and the report was adopted as a third round mutual evaluation report at its 39 th Plenary (Strasbourg, 2-6 July 2012). © [2012] Committee of experts on the evaluation of anti-money laundering measures and the financing of terrorism (MONEYVAL). All rights reserved. Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, save where otherwise stated. For any use for commercial purposes, no part of this publication may be translated, reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic (CD-Rom, Internet, etc) or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system without prior permission in writing from the MONEYVAL Secretariat, Directorate General of Human Rights and Rule of Law, Council of Europe (F-67075 Strasbourg or [email protected] ). 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. PREFACE AND SCOPE OF EVALUATION............................................................................................ 5 II. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY....................................................................................................................... -

Why Vatican II Happened the Way It Did, and Who’S to Blame

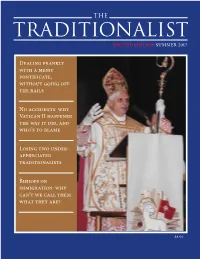

SPECIAL EDITION SUMMER 2017 Dealing frankly with a messy pontificate, without going off the rails No accidents: why Vatican II happened the way it did, and who’s to blame Losing two under- appreciated traditionalists Bishops on immigration: why can’t we call them what they are? $8.00 Publisher’s Note The nasty personal remarks about Cardinal Burke in a new EDITORIAL OFFICE: book by a key papal advisor, Cardinal Maradiaga, follow a pattern PO Box 1209 of other taunts and putdowns of a sitting cardinal by significant Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 cardinals like Wuerl and even Ouellette, who know that under [email protected] Pope Francis, foot-kissing is the norm. And everybody half- Your tax-deductible donations for the continu- alert knows that Burke is headed for Church oblivion—which ation of this magazine in print may be sent to is precisely what Wuerl threatened a couple of years ago when Catholic Media Apostolate at this address. he opined that “disloyal” cardinals can lose their red hats. This magazine exists to spotlight problems like this in the PUBLISHER/EDITOR: Church using the print medium of communication. We also Roger A. McCaffrey hope to present solutions, or at least cogent analysis, based upon traditional Catholic teaching and practice. Hence the stress in ASSOCIATE EDITORS: these pages on: Priscilla Smith McCaffrey • New papal blurtations, Church interference in politics, Steven Terenzio and novel practices unheard-of in Church history Original logo for The Traditionalist created by • Traditional Catholic life and beliefs, independent of AdServices of Hollywood, Florida. who is challenging these Can you help us with a donation? The magazine’s cover price SPECIAL THANKS TO: rorate-caeli.blogspot.com and lifesitenews.com is $8. -

Ave Papa Ave Papabile the Sacchetti Family, Their Art Patronage and Political Aspirations

FROM THE CENTRE FOR REFORMATION AND RENAISSANCE STUDIES Ave Papa Ave Papabile The Sacchetti Family, Their Art Patronage and Political Aspirations LILIAN H. ZIRPOLO In 1624 Pope Urban VIII appointed Marcello Sacchetti as depositary general and secret treasurer of the Apostolic Cham- ber, and Marcello’s brother, Giulio, bishop of Gravina. Urban later gave Marcello the lease on the alum mines of Tolfa and raised Giulio to the cardinalate. To assert their new power, the Sacchetti began commissioning works of art. Marcello discov- ered and promoted leading Baroque masters, such as Pietro da Cortona and Nicolas Poussin, while Giulio purchased works from previous generations. In the eighteenth century, Pope Benedict XIV bought the collection and housed it in Rome’s Capitoline Museum, where it is now a substantial portion of the museum’s collection. By focusing on the relationship between the artists in ser- vice and the Sacchetti, this study expands our knowledge of the artists and the complexity of the processes of agency in the fulfillment of commissions. In so doing, it underlines how the Sacchetti used art to proclaim a certain public image and to announce Cardinal Giulio’s candidacy to the papal throne. ______ copy(ies) Ave Papa Ave Papabile Payable by cheque (to Victoria University - CRRS) ISBN 978-0-7727-2028-2 or by Visa/Mastercard $24.50 Name as on card ___________________________________ (Outside Canada, please pay in US $.) Visa/Mastercard # _________________________________ Price includes applicable taxes. Expiry date _____________ Security code ______________ Send form with cheque/credit card Signature ________________________________________ information to: Publications, c/o CRRS Name ___________________________________________ 71 Queen’s Park Crescent East Address __________________________________________ Toronto, ON M5S 1K7 Canada __________________________________________ The Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies Victoria College in the University of Toronto Tel: 416-585-4465 Fax: 416-585-4430 [email protected] www.crrs.ca . -

UK Leaves Poorest to Balance the Budget

Friday 16th April 2021 • £2.40 • €2.70 Subscribers only pay £1.94 www.thecatholicuniverse.com UK leaves poorest to balance the budget Faith leaders united in attacking plans to slash foreign aid at time world is still reeling from Covid-19 pandemic Nick Benson They stress that “we must not walk Cardinal Vincent Nichols and the Arch- by on the other side”. bishop of Canterbury have joined Chancellor Rishi Sunak has de- forces to condemn cuts to the UK’s scribed the cut as a ‘temporary’ meas- Aid budget, saying that the move will ure to cope with the deficit caused by do “real damage” to Yemen, Syria, the Covid-19 pandemic, and that the South Sudan and other countries in 0.7 per cent target would return when crisis. finances allowed. The decision has also been attacked However, some MPs fear that the by Catholic aid agencies, who pointed reduction could be permanent. out that in the USA, President Biden “Saying the Government will only has asked Congress to increase aid do this ‘when the fiscal situation al- spending, saying it was crucial the lows’ is deeply worrying, suggesting Pope adds condolences as he world’s wealthiest nations acted to that it will act in contravention of its help the poorest as they struggled to legally binding target,” the Church come to terms with the impact of leaders said. Covid-19. “This promise, repeatedly made salutes Duke’s public service The UK government has said it even during the pandemic, has been would not meet the 0.7 per cent target broken and must be put right.” Nick Benson “commitment to the education -

Gregory the Great

GREGORY THE GREAT Gregory’s life culminated in his holding the office of pope (590–604). He is generally regarded as one of the outstanding figures in the long line of popes, and by the late ninth century had come to be known as ‘the Great’. He played a critical role in the history of his time, and is regarded as one of the four great fathers of the Western Church, alongside Ambrose, Jerome and Augustine. This volume provides an introduction to Gregory the Great’s life and works and to the most fascinating areas of his thinking. It includes English translations of his influential writings on such topics as the interpretation of the Bible and human personality types. These works show Gregory communicating what seem to be abstruse ideas to ordinary people, and they remain highly current today. John Moorhead teaches late antiquity and medieval history at the University of Queensland, Australia, where he is McCaughey Professor of History. His publications include Theoderic in Italy (1992), Ambrose of Milan (1999) and The Roman Empire Divided (2001). THE EARLY CHURCH FATHERS Edited by Carol Harrison University of Durham The Greek and Latin Fathers of the Church are central to the creation of Christian doctrine, yet often unapproachable because of the sheer volume of their writings and the relative paucity of accessible trans- lations. This series makes available translations of key selected texts by the major Fathers to all students of the Early Church. CYRIL OF JERUSALEM GREGORY OF NYSSA Edward Yarnold, S. J. Anthony Meredith, S. J. EARLY CHRISTIAN LATIN JOHN CHRYSOSTOM POETS Wendy Mayer and Pauline Allen Carolinne White JEROME CYRIL OF ALEXANDRIA Stefan Rebenich Norman Russell TERTULLIAN MAXIMUS THE CONFESSOR Geoffrey Dunn Andrew Louth ATHANASIUS IRENAEUS OF LYONS Khaled Anatolios Robert M. -

Commemorative Act: 30 Years of the Dicastery

COMMEMORATIVE ACT: 30 YEARS OF THE DICASTERY CHRONICLE On 12 June 2012, the Pontifical Council for Culture celebrated thirty years of its existence. In the morning, people who had been involved in the life of the Dicastery since its creation gathered in the church of Sant’Anna in the Vatican for a Eucharistic Celebration presided over by Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi. In the afternoon, the celebration continued with a Public Session held in the auditorium of our new building, Palazzo Pio X in via della Conciliazione, to reflect on the past, present and future of the Dicastery with the objectives outlined by John Paul II. In fact, the PCC was born after a long period of gestation on 20 May 1982 as a fruit of the Second Vatican Council. The ceremony was overseen by His Excellency the Delegate, Monsignor Carlos Azevedo and began with a brief greeting by the Secretary of the Council, His Excellency Monsignor Barthélemy Adoukonou. Aware of the history and prehistory of these last thirty years, the first moment of the commemorative act, which took the form of a triptych, was dedicated to the past. Monsignor Melchor Sánchez de Toca, undersecretary of the Dicastery illustrated its origins using his long study of the Dicastery’s genesis. With the help of Rai, the Italian State Television company, a film was produced and were given a preview after a brief introduction by Giovanni Minoli, Director of Rai Storia, the channel which would subsequently transmit the programme. The Council then offered flowers to the journalist Antonia Pillosio as a sign of thanks for the mediatic vision she brought to our work. -

In This Issue: Eucharistic Adoration 3 Our Lady’S Month 3 Rector’S Ruminations 4 News from the Vatican 5

12 May 2019 Fourth Sunday of Easter Weekly Bulletin for the Cathedral of St. Joseph, Wheeling, West Virginia Vol. 8, No. 24 In this Issue: Eucharistic Adoration 3 Our Lady’s Month 3 Rector’s Ruminations 4 News from the Vatican 5 Saint Joseph Cathedral Parish is called to spread the Gospel of Jesus Christ as a community. We are committed: to our urban neighborhoods, to being the Cathedral of the Diocese, and to fellowship, formation, sacrament, and prayer. Fourth Sunday of Easter Acts 13:14, 43-52 • Psalm 100:1-2, 3, 5 Revelation 7:9, 14-17 • John 10:27-30 Throughout the Easter season, our readings have given us glimpses into the life of the newborn Church and the bold witness ThisAt The Cathedral Week of the early disciples in spreading the Good News of Jesus Christ to all who would listen. These disciples were the first to live a May 12 - 19, 2019 stewardship way of life and their example is as relevant today as it was 2,000 years ago. In the First Reading, from the Acts of the Apostles, we catch vvvvv up with Paul and Barnabas in Antioch. While they certainly have some success in reaching many people there with the message of salvation, others are downright infuriated by their words and SUN FOURTH SUNDAY OF EASTER send them packing. Yet, we read that “the disciples were filled 12 Mother’s Day with joy and the Holy Spirit.” Overall, it seems as if Paul and (Sat) 6:00 pm Mass for John Davis Barnabas had failed in Antioch. -

The Holy See

The Holy See APOSTOLIC CONSTITUTION PASTOR BONUS JOHN PAUL, BISHOP SERVANT OF THE SERVANTS OF GOD FOR AN EVERLASTING MEMORIAL TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction I GENERAL NORMS Notion of Roman Curia (art. 1) Structure of the Dicasteries (arts. 2-10) Procedure (arts. 11-21) Meetings of Cardinals (arts. 22-23) Council of Cardinals for the Study of Organizational and Economic Questions of the Apostolic See (arts. 24-25) Relations with Particular Churches (arts. 26-27) Ad limina Visits (arts. 28-32) Pastoral Character of the Activity of the Roman Curia (arts. 33-35) Central Labour Office (art. 36) Regulations (arts. 37-38) II SECRETARIAT OF STATE (Arts. 39-47) 2 First Section (arts. 41-44) Second Section (arts. 45-47) III CONGREGATIONS Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (arts. 48-55) Congregation for the Oriental Churches (arts. 56-61) Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments (arts. 62-70) Congregation for the Causes of Saints (arts. 71-74) Congregation for Bishops (arts. 75-84) Pontifical Commission for Latin America (arts. 83-84) Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples (arts. 85-92) Congregation for the Clergy (arts. 93-104) Pontifical Commission Preserving the Patrimony of Art and History (arts. 99-104) Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and for Societies of Apostolic Life (arts. 105-111) Congregation of Seminaries and Educational Institutions (arts. 112-116) IV TRIBUNALS Apostolic Penitentiary (arts. 117-120) Supreme Tribunal of the Apostolic Signatura (arts. 121-125) Tribunal of the Roman Rota (arts. 126-130) V PONTIFICAL COUNCILS Pontifical Council for the Laity (arts. -

The Permission to Publish

THE PERMISSION TO PUBLISH A Resource for Diocesan and Eparchial Bishops on the Approvals Needed to Publish Various Kinds of Written Works Committee on Doctrine • United States Conference of Catholic Bishops The Permission to Publish A Resource for Diocesan and Eparchial Bishops on the Approvals Needed to Publish Various Kinds of Written Works Committee on Doctrine • United States Conference of Catholic Bishops The document The Permission to Publish: A Resource for Diocesan and Eparchial Bishops on the Approvals Needed to Publish Various Kinds of Written Works was developed as a resource by the Committee on Doctrine of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB). It was reviewed by the committee chairman, Archbishop William J. Levada, and has been author- ized for publication by the undersigned. Msgr. William P. Fay General Secretary, USCCB Excerpts from the Code of Canon Law: New English Translation. Translation of Codex Iuris Canonici prepared under the auspices of the Canon Law Society of America, Washington, D.C. © 1998. Used with permission. Excerpts from the Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches: New English Translation. Translation of Codex Canonum Ecclesiarum Orientalium pre- pared under the auspices of the Canon Law Society of America, Washington, D.C. © 2001. Used with permission. First Printing, June 2004 ISBN 1-57455-622-3 Copyright © 2004, United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Washington, D.C. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmit- ted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photo- copying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, with- out permission in writing from the copyright holder. -

OF MANY THINGS 106 West 56Th Street New York, NY 10019-3803 Ph: (212) 581-4640; Fax: (212) 399-3596 Rom 1951 to 1969 the State Are Not

OF MANY THINGS 106 West 56th Street New York, NY 10019-3803 Ph: (212) 581-4640; Fax: (212) 399-3596 rom 1951 to 1969 the State are not. Perhaps this is what is meant Subscriptions: (800) 627-9533 of Florida was represented when presidential aspirants say that www.americamedia.org facebook.com/americamag Fin the U.S. Senate by George “we” are going to “take our country twitter.com/americamag A. Smathers, a Miami attorney and back.” Perhaps they are suggesting that future used car salesman who is best Peoria should reclaim from New York PRESIDENT AND EDITOR IN CHIEF Matt Malone, S.J. remembered for his close friendships what is rightly theirs? Maybe that’s EXECUTIVE EDITORS with two U.S. presidents: John F. not what is meant, but then just who Robert C. Collins, S.J., Maurice Timothy Reidy Kennedy, with whom he would is the “our” in “we are going to take our MANAGING EDITOR Kerry Weber occasionally raise hell; and Richard country back?” And from whom are LITERARY EDITOR Raymond A. Schroth, S.J. Nixon, to whom he sold his Key they (and or we) taking it back? SENIOR EDITOR AND CHIEF CORRESPONDENT Kevin Clarke Biscayne home—what would become Such is the logic of demagogues, EDITOR AT LARGE James Martin, S.J. Nixon’s Southern White House. which would be as laughable as EXECUTIVE EDITOR, AMERICA FIlmS My favorite story about the Smather’s Redneck Speech if it weren’t Jeremy Zipple, S.J. otherwise nondescript Mr. Smathers for the fact that in the current political POETRY EDITOR Joseph Hoover, S.J.