About This Volume Gary Hoppenstand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Note to Users

NOTE TO USERS Page(s) not included in the original manuscript are unavailable from the author or university. The manuscript was microfilmed as received 88-91 This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. AccessinglUMI the World’s Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Mi 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8820263 Leigh Brackett: American science fiction writer—her life and work Carr, John Leonard, Ph.D. -

![The Nemedian Chroniclers #22 [WS16]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7322/the-nemedian-chroniclers-22-ws16-27322.webp)

The Nemedian Chroniclers #22 [WS16]

REHeapa Winter Solstice 2016 By Lee A. Breakiron A WORLDWIDE PHENOMENON Few fiction authors are as a widely published internationally as Robert E. Howard (e.g., in Bulgarian, Croatian, Czech, Dutch, Estonian, Finnish, French, German, Greek, Hungarian, Italian, Japanese, Lithuanian, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Slovak, Spanish, Swedish, Turkish, and Yugoslavian). As former REHupan Vern Clark states: Robert E. Howard has long been one of America’s stalwarts of Fantasy Fiction overseas, with extensive translations of his fiction & poetry, and an ever mushrooming distribution via foreign graphic story markets dating back to the original REH paperback boom of the late 1960’s. This steadily increasing presence has followed the growing stylistic and market influence of American fantasy abroad dating from the initial translations of H.P. Lovecraft’s Arkham House collections in Spain, France, and Germany. The growth of the HPL cult abroad has boded well for other American exports of the Weird Tales school, and with the exception of the Lovecraft Mythos, the fantasy fiction of REH has proved the most popular, becoming an international literary phenomenon with translations and critical publications in Spain, Germany, France, Greece, Poland, Japan, and elsewhere. [1] All this shows how appealing REH’s exciting fantasy is across cultures, despite inevitable losses in stylistic impact through translations. Even so, there is sometimes enough enthusiasm among readers to generate fandom activities and publications. We have already covered those in France. [2] Now let’s take a look at some other countries. GERMANY, AUSTRIA, AND SWITZERLAND The first Howard stories published in German were in the fanzines Pioneer #25 and Lands of Wonder ‒ Pioneer #26 (Austratopia, Vienna) in 1968 and Pioneer of Wonder #28 (Follow, Passau, Germany) in 1969. -

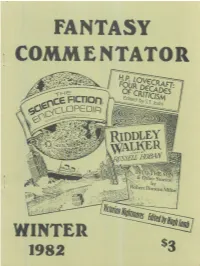

Fantasy Commentator EDITOR and PUBLISHER: CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: A

Fantasy Commentator EDITOR and PUBLISHER: CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: A. Langley Searles Lee Becker, T. G. Cockcroft, 7 East 235th St. Sam Moskowitz, Lincoln Bronx, N. Y. 10470 Van Rose, George T. Wetzel Vol. IV, No. 4 -- oOo--- Winter 1982 Articles Needle in a Haystack Joseph Wrzos 195 Voyagers Through Infinity - II Sam Moskowitz 207 Lucky Me Stephen Fabian 218 Edward Lucas White - III George T. Wetzel 229 'Plus Ultra' - III A. Langley Searles 240 Nicholls: Comments and Errata T. G. Cockcroft and 246 Graham Stone Verse It's the Same Everywhere! Lee Becker 205 (illustrated by Melissa Snowind) Ten Sonnets Stanton A. Coblentz 214 Standing in the Shadows B. Leilah Wendell 228 Alien Lee Becker 239 Driftwood B. Leilah Wendell 252 Regular Features Book Reviews: Dahl's "My Uncle Oswald” Joseph Wrzos 221 Joshi's "H. P. L. : 4 Decades of Criticism" Lincoln Van Rose 223 Wetzel's "Lovecraft Collectors Library" A. Langley Searles 227 Moskowitz's "S F in Old San Francisco" A. Langley Searles 242 Nicholls' "Science Fiction Encyclopedia" Edward Wood 245 Hoban's "Riddley Walker" A. Langley Searles 250 A Few Thorns Lincoln Van Rose 200 Tips on Tales staff 253 Open House Our Readers 255 Indexes to volume IV 266 This is the thirty-second number of Fantasy Commentator^ a non-profit periodical of limited circulation devoted to articles, book reviews and verse in the area of sci ence - fiction and fantasy, published annually. Subscription rate: $3 a copy, three issues for $8. All opinions expressed herein are the contributors' own, and do not necessarily reflect those of the editor or the staff. -

Searchers After Horror Understanding H

Mats Nyholm Mats Nyholm Searchers After Horror Understanding H. P. Lovecraft and His Fiction // Searchers After Horror Horror After Searchers // 2021 9 789517 659864 ISBN 978-951-765-986-4 Åbo Akademi University Press Tavastgatan 13, FI-20500 Åbo, Finland Tel. +358 (0)2 215 4793 E-mail: [email protected] Sales and distribution: Åbo Akademi University Library Domkyrkogatan 2–4, FI-20500 Åbo, Finland Tel. +358 (0)2 -215 4190 E-mail: [email protected] SEARCHERS AFTER HORROR Searchers After Horror Understanding H. P. Lovecraft and His Fiction Mats Nyholm Åbo Akademis förlag | Åbo Akademi University Press Åbo, Finland, 2021 CIP Cataloguing in Publication Nyholm, Mats. Searchers after horror : understanding H. P. Lovecraft and his fiction / Mats Nyholm. - Åbo : Åbo Akademi University Press, 2021. Diss.: Åbo Akademi University. ISBN 978-951-765-986-4 ISBN 978-951-765-986-4 ISBN 978-951-765-987-1 (digital) Painosalama Oy Åbo 2021 Abstract The aim of this thesis is to investigate the life and work of H. P. Lovecraft in an attempt to understand his work by viewing it through the filter of his life. The approach is thus historical-biographical in nature, based in historical context and drawing on the entirety of Lovecraft’s non-fiction production in addition to his weird fiction, with the aim being to suggest some correctives to certain prevailing critical views on Lovecraft. These views include the “cosmic school” led by Joshi, the “racist school” inaugurated by Houellebecq, and the “pulp school” that tends to be dismissive of Lovecraft’s work on stylistic grounds, these being the most prevalent depictions of Lovecraft currently. -

The Satanic Rituals Anton Szandor Lavey

The Rites of Lucifer On the altar of the Devil up is down, pleasure is pain, darkness is light, slavery is freedom, and madness is sanity. The Satanic ritual cham- ber is die ideal setting for the entertainment of unspoken thoughts or a veritable palace of perversity. Now one of the Devil's most devoted disciples gives a detailed account of all the traditional Satanic rituals. Here are the actual texts of such forbidden rites as the Black Mass and Satanic Baptisms for both adults and children. The Satanic Rituals Anton Szandor LaVey The ultimate effect of shielding men from the effects of folly is to fill the world with fools. -Herbert Spencer - CONTENTS - INTRODUCTION 11 CONCERNING THE RITUALS 15 THE ORIGINAL PSYCHODRAMA-Le Messe Noir 31 L'AIR EPAIS-The Ceremony of the Stifling Air 54 THE SEVENTH SATANIC STATEMENT- Das Tierdrama 76 THE LAW OF THE TRAPEZOID-Die elektrischen Vorspiele 106 NIGHT ON BALD MOUNTAIN-Homage to Tchort 131 PILGRIMS OF THE AGE OF FIRE- The Statement of Shaitan 151 THE METAPHYSICS OF LOVECRAFT- The Ceremony of the Nine Angles and The Call to Cthulhu 173 THE SATANIC BAPTISMS-Adult Rite and Children's Ceremony 203 THE UNKNOWN KNOWN 219 The Satanic Rituals INTRODUCTION The rituals contained herein represent a degree of candor not usually found in a magical curriculum. They all have one thing in common-homage to the elements truly representative of the other side. The Devil and his works have long assumed many forms. Until recently, to Catholics, Protestants were devils. To Protes- tants, Catholics were devils. -

Fafnir – Nordic Journal of Science Fiction and Fantasy Research Journal.Finfar.Org

ISSN: 2342-2009 Fafnir vol 2, iss 1, pages 29–30 Fafnir – Nordic Journal of Science Fiction and Fantasy Research journal.finfar.org A Book review: Andrzej Wicher, Piotr Spyra & Joanna Matyjaszczyk (eds.) – Basic Categories of Fantastic Literature Revisited. Markku SoikkeliSoikeli Andrzej Wicher, Piotr Spyra, and Joanna Matyjaszczyk (eds.). Basic Categories of Fantastic Literature Revisited. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014. ISBN-13: 978-1443866798. A collection of academic articles is like a collection of short stories: the differences between articles (or stories) are more interesting than the thematic similarities. The free play of imagination is breaking even the genre rules, and that is exactly what makes the stories (or articles on genre texts) so interesting. This Polish-British collection Basic Categories of Fantastic Literature Revisited (2014) is aiming to rethink the concept of the fantastic as it is defined in the theory of Tzvetan Todorov. As stated in Todorov's Introduction à la littérature fantastique (1970), there are three modes of fiction outside the great barrier of mainstream literature: the marvellous (with recognizable supernatural elements), the uncanny (with explanations about exceptional things), and the fantastic (with ambivalent signs of the non-natural). Todorov's definition of the fantastic is usually considered to be more anachronistic than the texts that it is used for, but there still remains the mystery of readers’ pleasure in the kind of "Todorovian hesitation". And it is here where this Polish-British collection of twelve researchers steps in. According to the publisher's info-blurb, the articles are "unified by a highly theoretical focus." But is there anything "highly theoretical" in Todorov's legacy? It may be a valuable goal to rethink the usability of Todorov's view of the fantastic, but the articles in this collection consist of quite usual academic matter with emphasis on case studies. -

Fantasy Commentator

Fantasy Commentator EDITOR AND PUBLISHER: CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: A. Langley Searles Lee Becker, Sam Moskowitz, 7 East 235 St., Bronx, N. Y. 10470 Lincoln Van Rose, George T. Wetzel « Vol. IV, No. 2 ----- oOo----- Winter 1979-80 M Articles 'Plus Ultra': an Unknown Science-Fiction Utopia A. Langley Searles 51 Man's Future W. Olaf Stapledon 62 Peace and Olaf Stapledon Sam Moskowitz 72 Some Thoughts on C. L. Moore Sam Moskowitz 85 Edward Lucas White: Notes for a Biography - I George T. Wetzel 94 Matthew H. Onderdonk, 1910-1979 A. Langley Searles 120 Verse Sonnets for the Space Age Lee Becker 60 Tom o' Bedlam's Song Francis Thompson 69 The Dance Edward Lucas White 114 Pictorial Drawings for "Tom o' Bedlam's Song" Norman Lindsay 68,70 Photograph of Olaf Stapledon Bruce Hopkins 76 Photographs of Edward Lucas White and His Home 107 Regular Features Book Reviews: Pohl's "Way the Future Was" Edward Wood 65 I Shiel's "Empress of the Earth" Sam Moskowitz 71 Asimov's "In Memory Yet Green" Lincoln Van Rose 90 Tips on Tales staff 81 Open House Our Readers 115 This is the thirtieth number of Fantasy Commentator3 a periodical devoted to arti cles, book reviews and verse in the area of science-fiction and fantasy, published annually. Subscription rate: $3 a copy, three issues for $8. All opinions ex pressed herein are the individual contributor's own and do not necessarily reflect those of the staff. Submissions are subject to minimal editorial revision if ne cessary. copyright 1979 ty A. Langley Searles FANTASY COMMENTATOR 51 Plus Ultra’ An Unknown Science-Fiction Utopia by A. -

Queer Geometry and Higher Dimensions: Mathematics in the Fiction of H.P. Lovecraft

Queer Geometry and Higher Dimensions: Mathematics in the fiction of H.P. Lovecraft Daniel M. Look St. Lawrence University Introduction My cynicism and skepticism are increasing, and from an entirely new cause – the Einstein theory. The latest eclipse observations seem to place this system among the facts which cannot be dismissed, and assumedly it removes the last hold which reality or the universe can have on the independent mind. All is chance, accident, and ephemeral illusion - a fly may be greater than Arcturus, and Durfee Hill may surpass Mount Everest - assuming them to be removed from the present planet and differently environed in the continuum of space-time. All the cosmos is a jest, and fit to be treated only as a jest, and one thing is as true as another. 1 Howard Philips Lovecraft lived in a time of great scientific and mathematical advancement. The late 1800s to the early 1900s saw the discovery of x-rays, the identification of the electron, work on the structure of the atom, breakthroughs in the mathematical exploration of higher dimensions and alternate geometries, and, of course, Einstein's work on relativity. From his work on relativity, Einstein postulated that rays of light could be bent by celestial objects with a large enough gravitational pull. In 1919 and 1922 measurements were made during two eclipses that added support to this notion. This left Lovecraft unsettled, as seen in the above quote from a 1923 letter to James F. Morton. Lovecraft's distress is that it seems we can no longer trust our primary means of understanding the world around us. -

New Pulp-Related Books and Periodicals Available from Michael Chomko for July 2008

New pulp-related books and periodicals available from Michael Chomko for July 2008 In just two short weeks, the Dayton Convention Center will be hosting Pulpcon 37. It will begin on Thursday, July 31 and run through Sunday, August 3. This year’s convention will focus on Jack Williamson and the 70 th anniversary of John Campbell’s ascension to the editorship of Astounding. There will be two guests-of-honor, science-fiction writers Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle. Another highlight will be this year’s auction. It will feature many items from the estate of Ed Kessell, one of the guiding lights of the first Pulpcon. Included will be letters signed by Walter Gibson, E. Hoffmann Price, Walter Baumhofer, and others, as well as a wide variety of pulp magazines. For further information about Pulpcon 37, please visit the convention’s website at http://www.pulpcon.org/ Another highlight of Pulpcon is Tony Davis’ program book and fanzine, The Pulpster . As usual, I’ll be picking up copies of the issue for those of you who are unable to attend the convention. If you’d like me to acquire a copy for you, please drop me an email or letter as soon as possible. My addresses are listed below. Most likely, the issue will cost about seven dollars plus postage. For those who have been concerned, John Gunnison of Adventure House will be attending Pulpcon. If you plan to be at Pulpcon and would like me to bring along any books that I am holding for you, please let me know by Friday, July 25. -

Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: a Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Summer 8-7-2012 Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant James H. Shimkus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Shimkus, James H., "Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/95 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEACHING SPECULATIVE FICTION IN COLLEGE: A PEDAGOGY FOR MAKING ENGLISH STUDIES RELEVANT by JAMES HAMMOND SHIMKUS Under the Direction of Dr. Elizabeth Burmester ABSTRACT Speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, and horror) has steadily gained popularity both in culture and as a subject for study in college. While many helpful resources on teaching a particular genre or teaching particular texts within a genre exist, college teachers who have not previously taught science fiction, fantasy, or horror will benefit from a broader pedagogical overview of speculative fiction, and that is what this resource provides. Teachers who have previously taught speculative fiction may also benefit from the selection of alternative texts presented here. This resource includes an argument for the consideration of more speculative fiction in college English classes, whether in composition, literature, or creative writing, as well as overviews of the main theoretical discussions and definitions of each genre. -

Arkham House Forthcoming List.Wpd

F O R T H C O M I N G P R O J E C T S 2011–2014 2012 The Mission Statement On the Road to Cinnabar: The Fiction of Edward Bryant, Consilio et Sapientia 1970-2010 Collected and edited by Jean-Philippe Gervais. In 1939, two successful authors, August Derleth and Donald Cover and internal art by Laurie Fraser Manifold. Wandrei, decided to publish a hardcover collection of short Hardcover edition limited to 1000. ISBN: 978-0-87954-191-9 stories by their late friend and mentor, H.P. Lovecraft. Since the author’s death in 1937, he was considered by many to be The Arkham Garland: An Anthology of Macabre Fiction the finest horror writer of the 20th century, yet no mainstream A active anthology. Introduced by David Drake. publisher was willing to publish a volume of his short fiction. Cover and endpaper artist John Linton. (See over.) Derleth and Wandrei named their new press Arkham House Hardcover edition limited to 1,000 copies. after the eerie New England village where most of Lovecraft’s ISBN: 978-0-87954-189-6 stories took place. Over the next seven decades, Arkham House published the best horror and supernatural fiction in The Ghostly Fiction of H. Russell Wakefield the world. A brother-in-arms press, Mycroft & Moran, issued Cover artist to be announced. Introduced by Barbara Roden mysteries. with Mystery Commentary by Douglas Greene Hardcover edition limited to 1,000 copies. 2010 – Progress Report ISBN: 978-0-87954-190-2 The Arkham Sampler is selling very well, and the edition is half sold out. -

Catalogue XV 116 Rare Works of Speculative Fiction

Catalogue XV 116 Rare Works Of Speculative Fiction About Catalogue XV Welcome to our 15th catalogue. It seems to be turning into an annual thing, given it was a year since our last catalogue. Well, we have 116 works of speculative fiction. Some real rarities in here, and some books that we’ve had before. There’s no real theme, beyond speculative fiction, so expect a wide range from early taproot texts to modern science fiction. Enjoy. About Us We are sellers of rare books specialising in speculative fiction. Our company was established in 2010 and we are based in Yorkshire in the UK. We are members of ILAB, the A.B.A. and the P.B.F.A. To Order You can order via telephone at +44(0) 7557 652 609, online at www.hyraxia.com, email us or click the links. All orders are shipped for free worldwide. Tracking will be provided for the more expensive items. You can return the books within 30 days of receipt for whatever reason as long as they’re in the same condition as upon receipt. Payment is required in advance except where a previous relationship has been established. Colleagues – the usual arrangement applies. Please bear in mind that by the time you’ve read this some of the books may have sold. All images belong to Hyraxia Books. You can use them, just ask us and we’ll give you a hi-res copy. Please mention this catalogue when ordering. • Toft Cottage, 1 Beverley Road, Hutton Cranswick, UK • +44 (0) 7557 652 609 • • [email protected] • www.hyraxia.com • Aldiss, Brian - The Helliconia Trilogy [comprising] Spring, Summer and Winter [7966] London, Jonathan Cape, 1982-1985.