The World's Most Popular Architecture the Technology and Interior of the Automobile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 3

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 3 Film Soleil D.K. Holm www.pocketessentials.com This edition published in Great Britain 2005 by Pocket Essentials P.O.Box 394, Harpenden, Herts, AL5 1XJ, UK Distributed in the USA by Trafalgar Square Publishing P.O.Box 257, Howe Hill Road, North Pomfret, Vermont 05053 © D.K.Holm 2005 The right of D.K.Holm to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may beliable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The book is sold subject tothe condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated, without the publisher’s prior consent, in anyform, binding or cover other than in which it is published, and without similar condi-tions, including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publication. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1–904048–50–1 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1 Book typeset by Avocet Typeset, Chilton, Aylesbury, Bucks Printed and bound by Cox & Wyman, Reading, Berkshire Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 5 Acknowledgements There is nothing -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. JA Jason Aldean=American singer=188,534=33 Julia Alexandratou=Model, singer and actress=129,945=69 Jin Akanishi=Singer-songwriter, actor, voice actor, Julie Anne+San+Jose=Filipino actress and radio host=31,926=197 singer=67,087=129 John Abraham=Film actor=118,346=54 Julie Andrews=Actress, singer, author=55,954=162 Jensen Ackles=American actor=453,578=10 Julie Adams=American actress=54,598=166 Jonas Armstrong=Irish, Actor=20,732=288 Jenny Agutter=British film and television actress=72,810=122 COMPLETEandLEFT Jessica Alba=actress=893,599=3 JA,Jack Anderson Jaimie Alexander=Actress=59,371=151 JA,James Agee June Allyson=Actress=28,006=290 JA,James Arness Jennifer Aniston=American actress=1,005,243=2 JA,Jane Austen Julia Ann=American pornographic actress=47,874=184 JA,Jean Arthur Judy Ann+Santos=Filipino, Actress=39,619=212 JA,Jennifer Aniston Jean Arthur=Actress=45,356=192 JA,Jessica Alba JA,Joan Van Ark Jane Asher=Actress, author=53,663=168 …….. JA,Joan of Arc José González JA,John Adams Janelle Monáe JA,John Amos Joseph Arthur JA,John Astin James Arthur JA,John James Audubon Jann Arden JA,John Quincy Adams Jessica Andrews JA,Jon Anderson John Anderson JA,Julie Andrews Jefferson Airplane JA,June Allyson Jane's Addiction Jacob ,Abbott ,Author ,Franconia Stories Jim ,Abbott ,Baseball ,One-handed MLB pitcher John ,Abbott ,Actor ,The Woman in White John ,Abbott ,Head of State ,Prime Minister of Canada, 1891-93 James ,Abdnor ,Politician ,US Senator from South Dakota, 1981-87 John ,Abizaid ,Military ,C-in-C, US Central Command, 2003- -

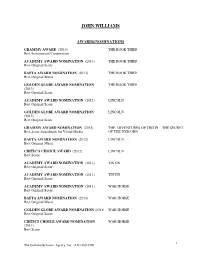

John Williams

JOHN WILLIAMS AWARDS/NOMINATIONS GRAMMY AWARD (201 4) THE BOOK THIEF Best Instrumental Composition ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2013) THE BOOK THIEF Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD NOMINATION (2013) THE BOOK THIEF Best Original Music GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD NOMINATION THE BOOK THIEF (2013) Best Original Score ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATI ON (2012 ) LINCOLN Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD NOMINATION LINCOLN (2012) Best Original Score GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (2012) THE ADVENTURES OF TINTIN – THE SECRET Best Score Soundtrack for Visual Media OF THE UNICORN BAFTA AWARD NOMINATIO N (2012 ) LINCOLN Best Original Music CRITIC’S CHOICE AWARD (2012) LINCOLN Best Score ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2011) TINTIN Best Original Score ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2011) TINTIN Best Original Score ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2011) WAR HORSE Best Ori ginal Score BAFTA AWARD NOMINATION (2011) WAR HORSE Best Original Music GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD NOMINATION (2011) WAR HORSE Best Original Score CRITICS CHOICE AWARD NOMINATION WAR HORSE (2011) Best Score 1 The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 JOHN WILLIAMS ANNIE AWARD NOMINATION (2011) TINTIN Best Music in a Feature Production EMMY AWARD (2009) GREAT PERFORMANCES Outstanding Original Main Title Theme Music GRAMMY AWARD (2008) “The Adventures of Mutt” Best Instrumental Composition from INDIANA JONES AND THE KINGDOM OF THE CRYSTAL SKULL GRAMMY AWARD (2006) “A Prayer for Peace” Best Instrumental Composition from MUNICH GRAMMY AWARD (2006) MEMOIRS OF A GEISHA Best Score Soundtrack Album GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (2006) -

Introduction 1 Situating the Controlled Body 2 Bondage and Discipline, Dominance and Submission, and Sadomasochism (BDSM) At

Notes Introduction 1. In many respects, Blaine’s London feat is part of that shift. Whereas his entombment in ice in New York in 2000 prompted a media focus on his pun- ishing preparations (see Anonymous 2000, 17; Gordon 2000a, 11 and 2000b, 17), his time in the box brought much ridicule and various attempts to make the experience more intense, for instance a man beating a drum to deprive Blaine of sleep and a ‘flash mob’ tormenting him with hamburgers. 2. For some artists, pain is fundamental to the performance, but Franko B uses local anaesthetic, as he considers the end effect more important than the pain. 3. BDSM is regarded by many as less pejorative than sadomasochism; others choose S&M, S/M and SM. Throughout the book I retain each author’s appel- lation but see them fitting into the overarching concept of BDSM. 4. Within the BDSM scene there are specific distinctions and pairings of tops/ bottoms, Doms/subs and Masters/slaves, with increasing levels of control of the latter in each pairing by the former; for instance, a bottom will be the ‘receiver’ or takes the ‘passive’ part in a scene, whilst a sub will surrender control of part of their life to their Dominant. For the purposes of this book, I use the terms top and bottom (except when citing opinions of others) to suggest the respec- tive positions as I am mostly referring to broader notions of control. 5. Stressing its performative qualities, the term ‘scene’ is frequently used for the engagement in actual BDSM acts; others choose the term ‘play’, which as well as stressing its separation from the real has the advantage of indicating it is governed by predetermined rules. -

November 2012 Calendar

November 2012 EXHIBITS In the Main Gallery TUESDAY SUNDAY MONDAY CHILDREN’S ILLUSTRATORS EXHIBI- 6 11 19 CHESS CLUB: All are welcome. Bring a AMPHION QUARTET: A performance of GREAT BOOKS DISCUSSION GROUP: A TION, November 1 through 30. Reception game if you have one. Tuesdays from 2 works by Wolf, Mendelssohn and Janacek. discussion of Fifth Business by Robertson & Signing: November 4. Sponsored by to 4 p.m. 3 p.m. Story in this issue. MAC Davis, continued. 1 pm Astoria Federal Savings, The Port Wash- ington Branch. Story on front page. NOVEMBER NOIR: Somewhere in the AFTERNOON AT THE OPERA: Don Night (1946-108 min.). An amnesiac WWII Giovanni. First performed in Prague in In the Martin Vogel Photography Gallery veteran (John Hodiak) searches for clues 1787, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Don PETER KAPLAN: Height Photography, to his identity, leading him to a hidden Giovanni ranks among the greatest of November 1 through December 30. Mr. suitcase containing two million dollars. operatic masterpieces, distinguished by Kaplan will talk about his life and work Director Joseph L. Mankiewicz rewrote MONDAY Lorenzo Da Ponte’s excellent libretto, as on Thursday, November 1 at 7:30 p.m. in Howard Dimsdale’s screenplay, with input 12 well as extraordinary music. Playwright VIRTUAL VISITS: The Frick Collection. the Martin Vogel Distinguished Photogra- from Lee Strasberg. 7:30 p.m. Join Ines Powell for the first program in and music critic George Bernard Shaw, phers Lecture. this new series. On Monday, December considered it a “perfect” opera. Described Don 10: The Hispanic Society of America. -

Children's Horror, PG-13 and the Emergent Millennial Pre-Teen

Children Beware! Children’s horror, PG-13 and the emergent Millennial pre-teen Filipa Antunes A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia School of Art, Media and American Studies December 2015 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. Filipa Antunes “Children beware!” Abstract This thesis is a study of the children’s horror trend of the 1980s and 1990s focused on the transformation of the concepts of childhood and horror. Specifically, it discusses the segmentation of childhood to include the pre-teen demographic, which emerges as a distinct Millennial figure, and the ramifications of this social and cultural shift both on the horror genre and the entertainment industry more broadly, namely through the introduction of the deeply impactful PG-13 rating. The work thus adds to debates on children and horror, examining and questioning both sides: notions of suitability and protection of vulnerable audiences, as well as cultural definitions of the horror genre and the authority behind them. The thesis moreover challenges the reasons behind academic dismissal of these texts, pointing out their centrality to on-going discussions over childhood, particularly the pre-teen demographic, and suggesting a different approach to the -

Bracketting Noir: Narrative and Masculinity in the Long Goodbye

Networking Knowledge Bracketting Noir (Jun. 2017) Bracketting Noir: Narrative and Masculinity in The Long Goodbye KYLE BARRETT, University of the West of Scotland ABSTRACT This paper will look at the subversion of tropes within The Long Goodbye (Robert Altman, 1973). Leigh Brackett, a veteran of the Hollywood studio system of the 1940s and 1950s, wrote the screenplay and previously had co-written Howard Hawks’ The Big Sleep (1944). Brackett adopted a different approach when working with Altman, maintaining his working practices of over-lapping dialogue and abandonment of traditional three-act structure. Brackett uses this opportunity of the less-restrictive production practices of the American New Wave of the 1970s to explore, and deconstruct, the myth of the detective. Throughout the narrative, Brackett populates the film with eccentric characters as Marlowe weaves his way through a labyrinthine plot and in many cases extreme representations of masculinity, evident in the scene where a gangster assaults his girlfriend with a coke bottle. Finally, Brackett presents Marlowe, played by Elliot Gould, as an out-of-time hero that needs updating. KEYWORDS Screenwriting, Gender, Film Noir, Masculinity, Narrative, New Hollywood Introduction What’s a man’s story? Conflict. Explosions. Killing. Guns. Special effects. A strong, heroic, nonemotional man doing physical action. Dinosaurs. Monsters. And, men might add, “They make lots of money.” That’s the stereotype and there’s some truth to it (Seger 2003, 111). Linda Seger’s statement above demonstrates the macho saturation of mainstream cinema. It is a male- dominated industry producing male-orientated films. However, looking over the history of cinema production we can see the key players are often women, ‘In the early years of filmmaking, women screenwriters outnumbered men ten to one, with the not surprising result of some classic films, roles, performances by and about women - many of whom wrote for, produced, requested and directed each other’ (McCreadie 2006, xii). -

Overdrive Poster Aafi

OVERDR IVE L.A. MOD ERN, 1960-2000 FEB 8-APR 17 CO-PRESENTED WITH THE NATIONAL BUILDING MUSEUM HARPER THE SAVAGE EYE In the latter half of the Feb 8* & 10 Mar 15† twentieth century, Los Angeles evolved into one of the most influ- POINT BLANK THE DRIVER ential industrial, eco- Feb 8*-11 Mar 16†, 21, 25 & 27 nomic and creative capitals in the world. THE SPLIT SMOG Between 1960 and Feb 9 & 12 Mar 22* 2000, Hollywood reflected the upheaval caused by L.A.’s rapid growth in films that wrestled with REPO MAN competing images of the city as a land that Feb 15-17 LOST HIGHWAY Mar 30 & Apr 1 scholar Mike Davis described as either “sun- shine” or “noir.” This duality was nothing new to THEY LIVE movies set in the City of Angels; the question Feb 21, 22 & 26 MULHOLLAND DR. simply became more pronounced—and of even Mar 31 & Apr 2 greater consequence—as the city expanded in size and global stature. The earnest and cynical L.A. STORY HEAT Feb 22* & 25 questioning evident in films of the 1960s and Apr 9 '70s is followed by postmodern irony and even- tually even nostalgia in films of the 1980s and LOS ANGELES PLAYS ITSELF JACKIE BROWN '90s, as the landscape of modern L.A. becomes Feb 23* Apr 11 & 12 increasingly familiar, with its iconic skyline of glass towers and horizontal blanket of street- THE PLAYER THE BIG LEBOWSKI lights and freeways spreading from the Holly- Feb 28 & Mar 6 Apr 11, 12, 15 & 17 wood Hills to Santa Monica and beyond. -

From Marcus Welby, M.D. to the Resident: the Changing Portrayal of Physicians in Tv Medical Dramas

RMC Original JMM ISSN electrónico: 1885-5210 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14201/rmc202016287102 FROM MARCUS WELBY, M.D. TO THE RESIDENT: THE CHANGING PORTRAYAL OF PHYSICIANS IN TV MEDICAL DRAMAS Desde Marcus Welby, M.D. hasta The resident: los cambios en las representaciones de los médicos en las series de televisión Irene CAMBRA-BADII1; Elena GUARDIOLA2; Josep-E. BAÑOS2 1Cátedra de Bioética. Universitat de Vic – Universitat Central de Catalunya.2 Facultad de Medicina. Universitat de Vic – Universitat Central de Catalunya (Spain). e-mail: [email protected] Fecha de recepción: 9 July 2019 Fecha de aceptación: 5 September 2019 Fecha del Avance On-Line: Fecha de publicación: 1 June 2020 Summary Over the years, the way medical dramas represent health professionals has changed. When the first medical dramas were broadcasted, the main characters were good, peaceful, intelligent, competent, empathic, and successful physicians. One of the most famous, even outside the US, was Marcus Welby M.D. (1969-1976) of David Victor –which this year marks 50 years since its first emission. This depiction began to change in the mid-1990s. While maintaining the over positive image of medical doctors, TV series started to put more emphasis on their negative characteristics and difficulties in their interpersonal relationships, such asER (TV) by Michael Crichton (United States) and House MD (TV) by David Shore (United States). In these series, physicians were portrayed as arrogant, greedy, and adulterous, and their diagnostic and therapeutic errors were exposed. The last two series are The Good Doctor (TV) by David Shore (United States), with a resident of surgery with autism and Savant syndrome, and The Resident (TV) by Amy Holden Jones, Hayley Schore and Roshan Sethi (United States), where serious institutional problems appear. -

Guide to the Ernie Smith Jazz Film Collection

Guide to the Ernie Smith Jazz Film Collection NMAH.AC.0491 Ben Pubols, Franklin A. Robinson, Jr., and Wendy Shay America's Jazz Heritage: A Partnership of the The Lila Wallace- Reader's Digest Fund and the Smithsonian Institution provided the funding to produce many of the video master and reference copies. 2001 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical...................................................................................................................... 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Ernie Smith Presentation Reels................................................................ 4 Series 2: Additional Titles..................................................................................... -

University of California Riverside

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Omega Men The Masculinist Discourse of Apocalyptic Manhood in Postwar American Cinema A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Ezekiel Crago June 2019 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Sherryl Vint, Co-Chairperson Dr. Derek Burrill, Co-Chairperson Dr. Carole-Anne Tyler Copyright by Ezekiel Crago 2019 The Dissertation of Ezekiel Crago is approved: __________________________________________ __________________________________________ Committee Co-Chairperson __________________________________________ Committee Co-Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgments I wish to thank my committee chairs, Sherryl Vint and Derek Burrill, for their constant help and encouragement. Carole-Anne Tyler helped me greatly by discussing gender and queer theory with me. Josh Pearson read drafts of chapters and gave me invaluable advice. I was able to work out chapters by presenting them at the annual conference of the Science Fiction Research Association, and I am grateful to the members of the organization for being so welcoming. I owe Erika Anderson undying gratitude for meticulously aiding me in research and proofreading the entire project. iv ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Omega Men The Masculinist Discourse of Apocalyptic Manhood in Postwar American Cinema by Ezekiel Crago Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Program in English University of California, Riverside, June 2019 Dr. Sherryl Vint, Co-Chairperson Dr. Derek Burrill, Co-Chairperson This study investigates anxieties over the role of white masculinity in American society after World War Two articulated in speculative films of the post-apocalypse. It treats the nascent genre of films as attempts to recenter white masculinity in the national imagination while navigating the increased visibility of this subject position, one that maintains dominance in society through its invisibility as superordinate standard of manhood. -

Columbia Pictures: Portrait of a Studio

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Film and Media Studies Arts and Humanities 1992 Columbia Pictures: Portrait of a Studio Bernard F. Dick Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Dick, Bernard F., "Columbia Pictures: Portrait of a Studio" (1992). Film and Media Studies. 8. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_film_and_media_studies/8 COLUMBIA PICTURES This page intentionally left blank COLUMBIA PICTURES Portrait of a Studio BERNARD F. DICK Editor THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Copyright © 1992 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2010 Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com Cataloging-in-Publication Data for the hardcover edition is available from the Library of Congress ISBN 978-0-8131-3019-4 (pbk: alk. paper) This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.