Bracketting Noir: Narrative and Masculinity in the Long Goodbye

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Long Goodbye I 1973 Directed by Robert Altman

TCM BREAKFAST CLUB SCREENING The Long Goodbye I 1973 Directed by Robert Altman With characteristic fearlessness, director Robert Altman dared to offend the purists with his 1970s interpretation of the Raymond Chandler classic The Long Goodbye (1973). It turned out to be a triumph for both him and its star, Elliott Gould. TCM writer David Humphrey assesses the film and describes it as a fine tribute to Altman, who died on November 20 at the age of 81. Raymond Chandler devotees were perhaps entitled to feel screen, and plainly gave priority to injecting comedy into the nervous at the news that Elliot Gould had been cast as Philip persona of Chandler’s sardonic, hardbitten private detective. For Marlowe in the 1973 movie The Long Goodbye. Bogart may have Brackett it was a return to familiar territory, as he had co-written been dead for 16 years, but many believed – and still do – that the script for Chandler‘s The Big Sleep (1946) with Bogie as his Marlowe was the definitive one. Anyone else taking the role Marlowe, 27 years earlier. The tale is satisfyingly labyrinthine in of the LA gumshoe would be like Rumpole without Leo McKern, the Chandler tradition: chain-smoking private eye Marlowe they reasoned, or Flash Gordon without Buster Crabbe. They had drives a friend from Los Angeles South to the Tijuana border and not banked on two crucial components: Robert Altman being in on returning finds his apartment swarming with LAPD’s finest, the director’s chair, and Gould on the top of his not who duly announce that he’s under arrest for abetting the inconsiderable form. -

HEROES and HERO WORSHIP.—Carlyle

z 2 J51 ^ 3 05 i 1 m Copyright, 1899, by Henry Altemus. Heroes and j ^ 'Hero Worship i CARLYLE ii i i]i8ijitimMin'iiwMM» i i jw [.TfciBBST,inrawn ^^ TttO/nAS Carlylc MERGES AND riERO WORSHIP #1^ ON HEROES, HERO-WORSHIP, AND THE HEROIC IN HISTORY. LECTURE I. THE HERO AS DIVINITY. ODIN. PAGANISM : SCAN^ DINAVIAN MYTHOLOGY. We have undertaken to discourse here for a little on Great Men, their manner of appearance in our world's business, how they have shaped themselves in the world's history, what ideas, men formed of them, what work they did ; —on Heroes, namely, and on their reception- and per- formance ; what I call Hero-worship and the Heroic in human affairs. Too evidently this is a large topic ; deserving quite other treatment than we can expect to give it at present. A large topic ; indeed, an illimitable one ; wide as Universal History itself. For, as I take it. Uni- versal History, the history of what man has- accomplished in this world, is at bottom the His- ! 6 Xecturcs on Ibcroes, tory of the Great Men who have worked here. They were the leaders of men, these great ones ; the modellers, patterns, and in a wide sense creators, of whatsoever the general mass of men contrived to do or to attain •, all things that we see standing accomplished in the world are properly the outer material result, the practical realization and embodiment, of Thoughts that dwelt in the Great Men sent into the world : the soul of the whole world's history, it may justly be considered, were the history of these. -

Table Talk Transcript June 17, 2021

School Lunch Tray Table Talk Transcript: June 17, 2021 Presenters: Speaker 1 – Shannon Yearwood, Speaker 2 – Susan Alston, Speaker 3 – Susan Fiore, Speaker 4 – Fionnuala Brown, Speaker 5 – Monica Pacheco Speaker 6 – Andy Paul, Speaker 7 – Teri Dandeneau, Sean Fogarty, Hostess – Michelle Rosado 0:03 Speaker 1 - Hi, and welcome to our last School Lunch Tray Table Talk for the School Year 2021. I’m Shannon Yearwood, the Education Manager with the Child Nutrition Programs at the Connecticut State Department of Education. 0:17 Joining me today is who I like to refer to as “Team Awesome,” because you have probably the best state administrators that any State could ask for, and they are right here as a resource for you to tap into. You know these are very strange times and just because this is the end of the Table Talk for this school year does not mean we are going anywhere. So certainly keep reaching out to us with your questions. 0:40 Um you guys know who your contacts are out there, who's on our team, so thank you so much for joining us. 0:45 Uh keep in mind, these at this will act as an open office hours, so certainly ask us your questions, type those into the box. We might run out of time, we have a packed agenda today, um and so that will help us be able to follow up with you. Or potentially develop some more resources that we know that that's some information that is good for the entire state, so thank you again for joining us, um and keep in mind these are recorded. -

Heroes (TV Series) - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Pagina 1 Di 20

Heroes (TV series) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Pagina 1 di 20 Heroes (TV series) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Heroes was an American science fiction Heroes television drama series created by Tim Kring that appeared on NBC for four seasons from September 25, 2006 through February 8, 2010. The series tells the stories of ordinary people who discover superhuman abilities, and how these abilities take effect in the characters' lives. The The logo for the series featuring a solar eclipse series emulates the aesthetic style and storytelling Genre Serial drama of American comic books, using short, multi- Science fiction episode story arcs that build upon a larger, more encompassing arc. [1] The series is produced by Created by Tim Kring Tailwind Productions in association with Starring David Anders Universal Media Studios,[2] and was filmed Kristen Bell primarily in Los Angeles, California. [3] Santiago Cabrera Four complete seasons aired, ending on February Jack Coleman 8, 2010. The critically acclaimed first season had Tawny Cypress a run of 23 episodes and garnered an average of Dana Davis 14.3 million viewers in the United States, Noah Gray-Cabey receiving the highest rating for an NBC drama Greg Grunberg premiere in five years. [4] The second season of Robert Knepper Heroes attracted an average of 13.1 million Ali Larter viewers in the U.S., [5] and marked NBC's sole series among the top 20 ranked programs in total James Kyson Lee viewership for the 2007–2008 season. [6] Heroes Masi Oka has garnered a number of awards and Hayden Panettiere nominations, including Primetime Emmy awards, Adrian Pasdar Golden Globes, People's Choice Awards and Zachary Quinto [2] British Academy Television Awards. -

Queer Orientation in Twentieth-Century American Literature

QUEER ORIENTATION IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AMERICAN LITERATURE By MICHAEL G. PARKER Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY August 2016 ii CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the dissertation of Michael Parker candidate for the degree of Doctorate Committee Chair T. Kenny Fountain Committee Member Michael Clune Committee Member Mary Grimm Committee Member Laura Hengehold Date of Defense 12 May 2016 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. iii Acknowledgements This dissertation is the culmination of seven years of idea generation and refinement regarding queer orientation. The project began during my first semester of graduate school when I wrote a seminar paper on the orientation of characters in Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye and Jazz toward their Southern homes after The Great Migration. Additional threads of this project can be found in papers I wrote about Hedwig and the Angry Inch, Moby Dick, and Alain Locke’s “The New Negro.” I am deeply grateful for those teachers who fostered my approach to literature by looking to orientation, including Thrity Umrigar and Marilyn Mobley. I consider myself lucky to have worked with and under a series of mentors who shaped this dissertation project directly. I want to thank Mary Grimm for her spirited discussions of the works of literature I selected and for directing me to include one work in particular. I am grateful for the experience and teaching of Michael Clune whose perspective on literature inspired much of my critical approach, specifically his emphasis on literature as doing something and as being worthy of close inspection. -

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 3

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 3 Film Soleil D.K. Holm www.pocketessentials.com This edition published in Great Britain 2005 by Pocket Essentials P.O.Box 394, Harpenden, Herts, AL5 1XJ, UK Distributed in the USA by Trafalgar Square Publishing P.O.Box 257, Howe Hill Road, North Pomfret, Vermont 05053 © D.K.Holm 2005 The right of D.K.Holm to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may beliable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The book is sold subject tothe condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated, without the publisher’s prior consent, in anyform, binding or cover other than in which it is published, and without similar condi-tions, including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publication. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1–904048–50–1 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1 Book typeset by Avocet Typeset, Chilton, Aylesbury, Bucks Printed and bound by Cox & Wyman, Reading, Berkshire Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 5 Acknowledgements There is nothing -

Sugarman Done Fly Away’: Kindred Threads of Female Madness and Male Flight in the Novels of Toni Morrison and Classical Greek Myth

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English Summer 8-7-2010 ‘Sugarman Done Fly Away’: Kindred Threads of Female Madness and Male Flight in the Novels of Toni Morrison and Classical Greek Myth Ebony O. McNeal Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation McNeal, Ebony O., "‘Sugarman Done Fly Away’: Kindred Threads of Female Madness and Male Flight in the Novels of Toni Morrison and Classical Greek Myth." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2010. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/92 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ‘SUGARMAN DONE FLY AWAY’: KINDRED THREADS OF FEMALE MADNESS AND MALE FLIGHT IN THE NOVELS OF TONI MORRISON AND CLASSICAL GREEK MYTH by EBONY OLIVIA MCNEAL Under the Direction of Kameelah Martin Samuel ABSTRACT Madness in women exists as a trope within the literature from the earliest of civilizations. This theme is evident and appears to possess a link with male dysfunction in several of Toni Morrison’s texts. Lack of maternal accountability has long served as a symptom of female mental instability as imposed by patriarchal thought. Mothers who have neglected or harmed their young across cultures and time periods have been forcibly branded with the mark of madness. Female characters in five of Morrison’s novels bear a striking resemblance to the female archetypes of ancient Greece. -

The Hero Is Hardboiled

Page 1 of 3 The Hero Is Hard-Boiled 'The Big Sleep' introduced Philip Marlowe and a new kind of mystery novel By LEONARD CASSUTO August 26, 2006 Raymond Chandler was the rare mystery writer who didn't care whodunit. "The Big Sleep," his first novel, appeared in 1939 and introduced Philip Marlowe, a detective who shows at least as much talent for wisecracks as for sleuthing. Marlowe's weathered dignity set the course of American detective fiction for generations. When Leigh Brackett collaborated on the screenplay for "The Big Sleep" in 1946 with William Faulkner (yes, that William Faulkner), the two found themselves so stymied by the plot turns that they couldn't tell who had murdered the chauffeur. Director Howard Hawks sent Chandler a telegram asking him who knocks the character off. "No idea," Chandler cabled in response. A grimy story involving pornography, drugs, and a particularly nasty hired killer in the employ of organized crime, "The Big Sleep" offers none of the clean, cathartic redemption that typically ended detective stories. "Crusts and fragments of greasy newspaper" litter Chandler's Depression-era Los Angeles, along with used condoms and "oil-scummed water." Marlowe solves the murders, more or less, but the solution doesn't leach the "hidden sadism" (as Chandler later called it) from his surroundings. A sordid mystery with a plot so incoherent that you can't tell who killed whom would not appear destined for classic status. In fact, "The Big Sleep" had a rocky debut. Though issued by the prestigious publisher Alfred A. Knopf, the novel sold a meager 12,500 copies in the U.S. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. JA Jason Aldean=American singer=188,534=33 Julia Alexandratou=Model, singer and actress=129,945=69 Jin Akanishi=Singer-songwriter, actor, voice actor, Julie Anne+San+Jose=Filipino actress and radio host=31,926=197 singer=67,087=129 John Abraham=Film actor=118,346=54 Julie Andrews=Actress, singer, author=55,954=162 Jensen Ackles=American actor=453,578=10 Julie Adams=American actress=54,598=166 Jonas Armstrong=Irish, Actor=20,732=288 Jenny Agutter=British film and television actress=72,810=122 COMPLETEandLEFT Jessica Alba=actress=893,599=3 JA,Jack Anderson Jaimie Alexander=Actress=59,371=151 JA,James Agee June Allyson=Actress=28,006=290 JA,James Arness Jennifer Aniston=American actress=1,005,243=2 JA,Jane Austen Julia Ann=American pornographic actress=47,874=184 JA,Jean Arthur Judy Ann+Santos=Filipino, Actress=39,619=212 JA,Jennifer Aniston Jean Arthur=Actress=45,356=192 JA,Jessica Alba JA,Joan Van Ark Jane Asher=Actress, author=53,663=168 …….. JA,Joan of Arc José González JA,John Adams Janelle Monáe JA,John Amos Joseph Arthur JA,John Astin James Arthur JA,John James Audubon Jann Arden JA,John Quincy Adams Jessica Andrews JA,Jon Anderson John Anderson JA,Julie Andrews Jefferson Airplane JA,June Allyson Jane's Addiction Jacob ,Abbott ,Author ,Franconia Stories Jim ,Abbott ,Baseball ,One-handed MLB pitcher John ,Abbott ,Actor ,The Woman in White John ,Abbott ,Head of State ,Prime Minister of Canada, 1891-93 James ,Abdnor ,Politician ,US Senator from South Dakota, 1981-87 John ,Abizaid ,Military ,C-in-C, US Central Command, 2003- -

The Lady in the Lake 4 5 by Raymond Chandler 6

Penguin Readers Factsheets level E Teacher’s notes 1 2 3 The Lady in the Lake 4 5 by Raymond Chandler 6 ELEMENTARY SUMMARY he Lady in the Lake, first published in 1943, is the As Chandler’s reputation grew, he was employed as a T fourth of Raymond Chandler’s great detective screenwriter in Hollywood, and after Humphrey Bogart stories featuring private detective Philip Marlowe. and Lauren Bacall starred in a film of The Big Sleep he As usual, Marlowe is employed to find a missing person, became world famous. In later life he became increasingly in this case the wife of Derace Kingsley, but in the course dependent on alcohol but he was recognized before he THE LADY IN LAKE of his investigation he uncovers a series of related crimes. died in 1959 as the outstanding writer of detective stories When Marlowe tries to interview Mrs Kingsley’s lover, in the USA. Lavery, he arouses the suspicions of a Doctor Almore, who lives opposite, and is warned off by a detective BACKGROUND AND THEMES named Degarmo. At Kingsley’s house in the mountains, Marlowe and the caretaker, Bill Chess, find the body of a The first detective stories were published in English in the woman in the lake, the face now unrecognizable but mid-nineteenth century, but they really became popular in apparently that of Chess’s wife, Muriel. the 1890s when Sir Arthur Conan Doyle created the private detective Sherlock Holmes. In the Sherlock Marlowe puts together the career of a woman called Holmes stories and those of writers like Agatha Christie Mildred Haviland. -

John Williams

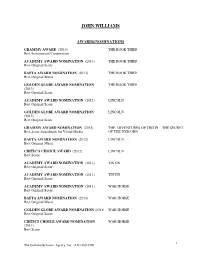

JOHN WILLIAMS AWARDS/NOMINATIONS GRAMMY AWARD (201 4) THE BOOK THIEF Best Instrumental Composition ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2013) THE BOOK THIEF Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD NOMINATION (2013) THE BOOK THIEF Best Original Music GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD NOMINATION THE BOOK THIEF (2013) Best Original Score ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATI ON (2012 ) LINCOLN Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD NOMINATION LINCOLN (2012) Best Original Score GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (2012) THE ADVENTURES OF TINTIN – THE SECRET Best Score Soundtrack for Visual Media OF THE UNICORN BAFTA AWARD NOMINATIO N (2012 ) LINCOLN Best Original Music CRITIC’S CHOICE AWARD (2012) LINCOLN Best Score ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2011) TINTIN Best Original Score ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2011) TINTIN Best Original Score ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2011) WAR HORSE Best Ori ginal Score BAFTA AWARD NOMINATION (2011) WAR HORSE Best Original Music GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD NOMINATION (2011) WAR HORSE Best Original Score CRITICS CHOICE AWARD NOMINATION WAR HORSE (2011) Best Score 1 The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 JOHN WILLIAMS ANNIE AWARD NOMINATION (2011) TINTIN Best Music in a Feature Production EMMY AWARD (2009) GREAT PERFORMANCES Outstanding Original Main Title Theme Music GRAMMY AWARD (2008) “The Adventures of Mutt” Best Instrumental Composition from INDIANA JONES AND THE KINGDOM OF THE CRYSTAL SKULL GRAMMY AWARD (2006) “A Prayer for Peace” Best Instrumental Composition from MUNICH GRAMMY AWARD (2006) MEMOIRS OF A GEISHA Best Score Soundtrack Album GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (2006) -

Introduction 1 Situating the Controlled Body 2 Bondage and Discipline, Dominance and Submission, and Sadomasochism (BDSM) At

Notes Introduction 1. In many respects, Blaine’s London feat is part of that shift. Whereas his entombment in ice in New York in 2000 prompted a media focus on his pun- ishing preparations (see Anonymous 2000, 17; Gordon 2000a, 11 and 2000b, 17), his time in the box brought much ridicule and various attempts to make the experience more intense, for instance a man beating a drum to deprive Blaine of sleep and a ‘flash mob’ tormenting him with hamburgers. 2. For some artists, pain is fundamental to the performance, but Franko B uses local anaesthetic, as he considers the end effect more important than the pain. 3. BDSM is regarded by many as less pejorative than sadomasochism; others choose S&M, S/M and SM. Throughout the book I retain each author’s appel- lation but see them fitting into the overarching concept of BDSM. 4. Within the BDSM scene there are specific distinctions and pairings of tops/ bottoms, Doms/subs and Masters/slaves, with increasing levels of control of the latter in each pairing by the former; for instance, a bottom will be the ‘receiver’ or takes the ‘passive’ part in a scene, whilst a sub will surrender control of part of their life to their Dominant. For the purposes of this book, I use the terms top and bottom (except when citing opinions of others) to suggest the respec- tive positions as I am mostly referring to broader notions of control. 5. Stressing its performative qualities, the term ‘scene’ is frequently used for the engagement in actual BDSM acts; others choose the term ‘play’, which as well as stressing its separation from the real has the advantage of indicating it is governed by predetermined rules.