Queer Orientation in Twentieth-Century American Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HEROES and HERO WORSHIP.—Carlyle

z 2 J51 ^ 3 05 i 1 m Copyright, 1899, by Henry Altemus. Heroes and j ^ 'Hero Worship i CARLYLE ii i i]i8ijitimMin'iiwMM» i i jw [.TfciBBST,inrawn ^^ TttO/nAS Carlylc MERGES AND riERO WORSHIP #1^ ON HEROES, HERO-WORSHIP, AND THE HEROIC IN HISTORY. LECTURE I. THE HERO AS DIVINITY. ODIN. PAGANISM : SCAN^ DINAVIAN MYTHOLOGY. We have undertaken to discourse here for a little on Great Men, their manner of appearance in our world's business, how they have shaped themselves in the world's history, what ideas, men formed of them, what work they did ; —on Heroes, namely, and on their reception- and per- formance ; what I call Hero-worship and the Heroic in human affairs. Too evidently this is a large topic ; deserving quite other treatment than we can expect to give it at present. A large topic ; indeed, an illimitable one ; wide as Universal History itself. For, as I take it. Uni- versal History, the history of what man has- accomplished in this world, is at bottom the His- ! 6 Xecturcs on Ibcroes, tory of the Great Men who have worked here. They were the leaders of men, these great ones ; the modellers, patterns, and in a wide sense creators, of whatsoever the general mass of men contrived to do or to attain •, all things that we see standing accomplished in the world are properly the outer material result, the practical realization and embodiment, of Thoughts that dwelt in the Great Men sent into the world : the soul of the whole world's history, it may justly be considered, were the history of these. -

Table Talk Transcript June 17, 2021

School Lunch Tray Table Talk Transcript: June 17, 2021 Presenters: Speaker 1 – Shannon Yearwood, Speaker 2 – Susan Alston, Speaker 3 – Susan Fiore, Speaker 4 – Fionnuala Brown, Speaker 5 – Monica Pacheco Speaker 6 – Andy Paul, Speaker 7 – Teri Dandeneau, Sean Fogarty, Hostess – Michelle Rosado 0:03 Speaker 1 - Hi, and welcome to our last School Lunch Tray Table Talk for the School Year 2021. I’m Shannon Yearwood, the Education Manager with the Child Nutrition Programs at the Connecticut State Department of Education. 0:17 Joining me today is who I like to refer to as “Team Awesome,” because you have probably the best state administrators that any State could ask for, and they are right here as a resource for you to tap into. You know these are very strange times and just because this is the end of the Table Talk for this school year does not mean we are going anywhere. So certainly keep reaching out to us with your questions. 0:40 Um you guys know who your contacts are out there, who's on our team, so thank you so much for joining us. 0:45 Uh keep in mind, these at this will act as an open office hours, so certainly ask us your questions, type those into the box. We might run out of time, we have a packed agenda today, um and so that will help us be able to follow up with you. Or potentially develop some more resources that we know that that's some information that is good for the entire state, so thank you again for joining us, um and keep in mind these are recorded. -

Heroes (TV Series) - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Pagina 1 Di 20

Heroes (TV series) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Pagina 1 di 20 Heroes (TV series) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Heroes was an American science fiction Heroes television drama series created by Tim Kring that appeared on NBC for four seasons from September 25, 2006 through February 8, 2010. The series tells the stories of ordinary people who discover superhuman abilities, and how these abilities take effect in the characters' lives. The The logo for the series featuring a solar eclipse series emulates the aesthetic style and storytelling Genre Serial drama of American comic books, using short, multi- Science fiction episode story arcs that build upon a larger, more encompassing arc. [1] The series is produced by Created by Tim Kring Tailwind Productions in association with Starring David Anders Universal Media Studios,[2] and was filmed Kristen Bell primarily in Los Angeles, California. [3] Santiago Cabrera Four complete seasons aired, ending on February Jack Coleman 8, 2010. The critically acclaimed first season had Tawny Cypress a run of 23 episodes and garnered an average of Dana Davis 14.3 million viewers in the United States, Noah Gray-Cabey receiving the highest rating for an NBC drama Greg Grunberg premiere in five years. [4] The second season of Robert Knepper Heroes attracted an average of 13.1 million Ali Larter viewers in the U.S., [5] and marked NBC's sole series among the top 20 ranked programs in total James Kyson Lee viewership for the 2007–2008 season. [6] Heroes Masi Oka has garnered a number of awards and Hayden Panettiere nominations, including Primetime Emmy awards, Adrian Pasdar Golden Globes, People's Choice Awards and Zachary Quinto [2] British Academy Television Awards. -

Sugarman Done Fly Away’: Kindred Threads of Female Madness and Male Flight in the Novels of Toni Morrison and Classical Greek Myth

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English Summer 8-7-2010 ‘Sugarman Done Fly Away’: Kindred Threads of Female Madness and Male Flight in the Novels of Toni Morrison and Classical Greek Myth Ebony O. McNeal Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation McNeal, Ebony O., "‘Sugarman Done Fly Away’: Kindred Threads of Female Madness and Male Flight in the Novels of Toni Morrison and Classical Greek Myth." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2010. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/92 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ‘SUGARMAN DONE FLY AWAY’: KINDRED THREADS OF FEMALE MADNESS AND MALE FLIGHT IN THE NOVELS OF TONI MORRISON AND CLASSICAL GREEK MYTH by EBONY OLIVIA MCNEAL Under the Direction of Kameelah Martin Samuel ABSTRACT Madness in women exists as a trope within the literature from the earliest of civilizations. This theme is evident and appears to possess a link with male dysfunction in several of Toni Morrison’s texts. Lack of maternal accountability has long served as a symptom of female mental instability as imposed by patriarchal thought. Mothers who have neglected or harmed their young across cultures and time periods have been forcibly branded with the mark of madness. Female characters in five of Morrison’s novels bear a striking resemblance to the female archetypes of ancient Greece. -

“THERE WILL BE TIME”: HEROISM, TEMPORALITY, and the SEARCH for OPPORTUNITY in MODERN LITERATURE by JOSEPH RUSSELL LEASE (Und

“THERE WILL BE TIME”: HEROISM, TEMPORALITY, AND THE SEARCH FOR OPPORTUNITY IN MODERN LITERATURE by JOSEPH RUSSELL LEASE (Under the Direction of Jed Rasula) ABSTRACT This dissertation focuses on the convergence of heroism and temporality in Modernist literature. Its purpose is to illuminate both the ways in which changes in the perception of time transformed the portrayal of potential hero figures and, more importantly, how a viable alternative to the frequently assumed “death” of the hero within that period went largely unnoticed. The hero figure (who does the “right” thing, for the “right” reason, at the “right” time) is largely missing from literature of the time period because one or more of the elements of the formula is not met, and there are particular challenges during the decades in question to finding the “right” time to act due to an imbalance in Western cultural perceptions of temporality that favored an exclusively quantitative model over one that balanced both quantitative and qualitative aspects, such as that favored by the Greeks and demonstrated through the concepts of chronos and kairos. I highlight the consequences of the Modernist, chronocentric temporal model by examining different works that illustrate the difficulties of creating and presenting heroes in a world in which the timing of heroic action is nearly impossible to get right. Moreover, the selected authors’ disparate backgrounds and literary interests underscore that the question of heroic viability was of enough concern to appear frequently and across a broad spectrum of Western literature during the period in question. Specific examples include an analysis of four novels by Joseph Conrad that tracks his portrayals of the nature of heroism in the modern world; an examination of two specific forms of kairic failure—akairic desire and akairic environment, both of which permeate Modernism—found within works by T. -

Time and the Vanities of Existence in Antun Šoljan's Fiction

Slovo. Journal of Slavic Languages, Literatures and Cultures ISSN 2001–7395 No. 55, 2014, pp. 60–76 Time and the Vanities of Existence in Antun Šoljan’s Fiction Denis Crnković Russian & Eastern European Studies, Gustavus Adolphus College [email protected] Abstract This paper explores the theme of hope and hopelessness in a selection of Antun Šoljan’s stories and novels and how the author creates in his heroes an interior atmosphere of inquiry that is paradoxically laden with uncertainty and the human instinct to move forward. A “parabolic moralist” (as Davor Kapetanić has called him), Šoljan depicts the world as more than a simple continuity of events, political, personal, private or public. His major concern is to make sense of man’s existence in a universe that confronts him with both linear time and a repetitive or circular series of events. Examining the apparent contradictions of linear vs. circular existence, the author often places his characters “out of time” and analyzes any given life by finding its important events, actions and desires. While Šoljan’s heroes often conclude that temporal things are of little lasting value, he leaves his philosophically and psychologically battered heroes with at least a small possibility of hope. Antun Šoljan, the undisputed voice of conscience in Yugoslav and Croatian literature for four decades after World War II, was a tireless writer of essays, plays, translations, novels and short stories. Because of its preoccupation with human existence in the midst of an oppressive political and social regime, his fiction is most often associated with that of the great existentialist writers of the mid-twentieth century. -

Culture and Climate Change: Narratives

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Open Research Online Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Culture and Climate Change: Narratives Edited Book How to cite: Smith, Joe; Tyszczuk, Renata and Butler, Robert eds. (2014). Culture and Climate Change: Narratives. Culture and Climate Change, 2. Cambridge, UK: Shed. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2014 Shed and the individual contributors Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://www.open.ac.uk/researchcentres/osrc/files/osrc/NARRATIVES.pdf Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Culture and Climate Change: Narratives ALICE BELL ROBERT BUTLER TAN COPSEY KRIS DE MEYER NICK DRAKE KATE FLETCHER CASPAR HENDERSON ISABEL HILTON CHRIS HOPE GEORGE MARSHALL RUTH PADEL JAMES PAINTER KELLIE C. PAYNE MIKE SHANAHAN BRADON SMITH JOE SMITH ZOË SVENDSEN RENATA TYSZCZUK MARINA WARNER CHRIS WEST Contributors BARRY WOODS Culture and Climate Change: Narratives Edited by Joe Smith, Renata Tyszczuk and Robert Butler Published by Shed, Cambridge Contents Editors: Joe Smith, Renata Tyszczuk and Robert Butler Design by Hyperkit Acknowledgements 4 © 2014 Shed and the individual contributors Introduction: What sort of story is climate change? 6 No part of this book may be reproduced in any Six essays form, apart from the quotation of brief passages Making a drama out of a crisis Robert Butler 11 for the purpose of review, without the written consent of the publishers. -

Heroes and Philosophy

ftoc.indd viii 6/23/09 10:11:32 AM HEROES AND PHILOSOPHY ffirs.indd i 6/23/09 10:11:11 AM The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series Series Editor: William Irwin South Park and Philosophy Edited by Robert Arp Metallica and Philosophy Edited by William Irwin Family Guy and Philosophy Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski The Daily Show and Philosophy Edited by Jason Holt Lost and Philosophy Edited by Sharon Kaye 24 and Philosophy Edited by Richard Davis, Jennifer Hart Week, and Ronald Weed Battlestar Galactica and Philosophy Edited by Jason T. Eberl The Offi ce and Philosophy Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski Batman and Philosophy Edited by Mark D. White and Robert Arp House and Philosophy Edited by Henry Jacoby Watchmen and Philosophy Edited by Mark D. White X-Men and Philosophy Edited by Rebecca Housel and J. Jeremy Wisnewski Terminator and Philosophy Edited by Richard Brown and Kevin Decker ffirs.indd ii 6/23/09 10:11:12 AM HEROES AND PHILOSOPHY BUY THE BOOK, SAVE THE WORLD Edited by David Kyle Johnson John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ffirs.indd iii 6/23/09 10:11:12 AM This book is printed on acid-free paper. Copyright © 2009 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or autho- rization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750–8400, fax (978) 646–8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. -

Skagit County Planning Commission Deliberations: Extending Preliminary Approval Time for Short Plats and Plats February 6, 2018

Skagit County Planning Commission Deliberations: Extending Preliminary Approval Time for Short Plats and Plats February 6, 2018 Planning Commissioners: Tim Raschko, Chair (absent) Kathy Mitchell, Vice Chair/Acting Chair Annie Lohman Mark Lundsten Tammy Candler Hollie Del Vecchio Josh Axthelm Martha Rose Amy Hughes Staff: Hal Hart, Planning Director Ryan Walters, Assistant Planning Director Stacie Pratschner, Senior Planner Acting Chair Kathy Mitchell: Good evening. I’d like to call to order the Planning Commission meeting for Tuesday, February 6th, 2018. Welcome, everybody (gavel). To begin with, I’d like to ask everybody take a look at the agenda. Number 4, the way we had put it out before we had put out number 4 was going to be Public Remarks. So we do need a – we did make a correction there, but does anybody else see any other additions or corrections or changes to the agenda? (silence) Chair Mitchell: Seeing none, Stacie, did you have anything else to say? Stacie Pratschner: Yeah, thank you. I would just follow up – thank you, Chair – with item number 4. It had been printed saying it was going to be a public hearing, but this evening we are doing deliberations. We held the public hearing for the plat extensions on January 23rd. Thank you. Chair Mitchell: Thank you. Normally we would also have Public Remarks next, but seeing as there’s nobody in the audience tonight I think we’ll just blow past number 3 and head for deliberations. Annie Lohman: Number 2? Mark Lundsten: What about number 2? Chair Mitchell: Oh, excuse me! Our guest! Stacie, could you please welcome our guest and introduce us, please? Ms. -

The World Needs Heroes Fight for the Future Together

THE WORLD NEEDS HEROES FIGHT FOR THE FUTURE TOGETHER Teams of heroes do battle across the planet. From protecting the secrets of the mysterious Temple of Anubis to safely escorting an EMP device through King’s Row, the world is your battlefield. TAKE YOUR PLACE IN OVERWATCH® Clash on the battlefields of tomorrow and choose your hero from a diverse cast of soldiers, scientists, adventurers, and oddities. Bend time, defy physics, and unleash an array of extraordinary powers and weapons. Engage your enemies in iconic locations from around the globe in the ultimate team-based competitive game. 6V6 Team-based competitive gameplay. Diverse heroes with unique sets of 29 devastating and game-changing abilities. Diverse heroes with unique sets of 19 devastating and game-changing abilities. Game modes, each with different objectives: 4 Assault, Escort, Hybrid, and Control. PLAY YOUR ROLE CHOOSE YOUR HERO Whether you’re taking down key targets, holding the front line, providing cover with an energy shield, or healing teammates, your hero’s abilities are designed to complement your team. Deploying your abilities in concert with your teammates is the key to victory. ROLE: DAMAGE Fearsome but fragile damage heroes wreak havoc on the enemy, but require backup to survive. Some specialize in pressing objectives, while others excel at defending key choke points. SOLDIER: 76 DOOMFIST REAPER TRACER PRIMARY WEAPON PRIMARY WEAPON PRIMARY WEAPON PRIMARY WEAPON HEAVY PULSE RIFLE HAND CANNON HELLFIRE SHOTGUNS PULSE PISTOLS ULTIMATE ABILITY ULTIMATE ABILITY ULTIMATE -

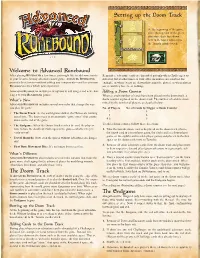

Advanced Runebound the Doom Track the Endgame Setting up The

Setting up the Doom Track At the beginning of the game, place the top card of the green adventure deck face-down next to the board adjacent to the Tamalir market stack. v 1.0 Welcome to Advanced Runebound After playing RUNEBOUND a few times, you might like to add some twists Remember, adventure cards are discarded not only when Challeenges are to your favorite fantasy adventure board game. ADVANCED RUNEBOUND defeated, but at other times as well: after encounters are resolved, for provides these twists—without adding any components—and lets you turn example, or when events are drawn that cannot be played, or when players RUNEBOUND into a whole new experience. use a card they have been holding. ADVANCED RUNEBOUND includes new options to add danger and new chal- Adding a Doom Counter lenges to your RUNEBOUND games. When a certain number of cards have been placed on the doom track, a What’s New doom counter is placed on the doom track. The number of cards is deter- mined by the number of players, as detailed below: ADVANCED RUNEBOUND includes several new rules that change the way you play the game: No. of Players No. of Cards to Trigger a Doom Counter 24 • The Doom Track: As the world grows darker, the Heroes are running 36 out of time. The doom track is an automatic “game timer” that counts 4-6 8 down to the end of the game. To add a doom counter, follow these directions: • The Endgame: When the Doom Track reaches the end, the players have to face the deadliest Challenges in the game—whether they’re 1. -

Maori Time: Notions of Space, Time and Building Form in the South Pacific Bill Mckay and Antonia Walmsley, UNITEC, New Zealand

Maori Time: Notions of Space, Time and Building Form in the South Pacific Bill McKay and Antonia Walmsley, UNITEC, New Zealand Abstract: This paper investigates how Western notions of space, time and terrestrial reality may affect the perception of building form in other cultures, and have constrained our understanding of the indigenous architecture of the South Pacific. Maori concepts of space and time are explored to add a further dimension to understanding the Meeting House, which is widely considered to be the primary building of Maori architecture. This paper argues that Maori architecture may not conform to the Western model of the three dimensional object in space, and could also be understood as existing in time rather than space. Keywords: Architecture; time; Maori Introduction This paper investigates how Western notions of space, time and terrestrial reality may affect the perception of building form in other cultures, and have constrained our understanding of the indigenous architecture of the South Pacific. Maori concepts of space and time are explored to add a further dimension to understanding the Meeting House, which is widely considered to be the primary building of Maori architecture. This paper argues that Maori architecture may not conform to the Western model of the three dimensional object in space, and could also be understood as existing in time rather than space. In August 1982, New Zealand Prime Minister Rob Muldoon found himself running behind the day’s schedule of events. On his arrival at a function for Australian schoolchildren he commented that ‘Maori time’ was the reason for his late arrival, as he had just come from a conference of Maori elders (Auckland Star, 1982).