Children's Horror, PG-13 and the Emergent Millennial Pre-Teen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neues Textdokument (2).Txt

Filmliste Liste de filme DVD Münchhaldenstrasse 10, Postfach 919, 8034 Zürich Tel: 044/ 422 38 33, Fax: 044/ 422 37 93 www.praesens.com, [email protected] Filmnr Original Titel Regie 20001 A TIME TO KILL Joel Schumacher 20002 JUMANJI 20003 LEGENDS OF THE FALL Edward Zwick 20004 MARS ATTACKS! Tim Burton 20005 MAVERICK Richard Donner 20006 OUTBREAK Wolfgang Petersen 20007 BATMAN & ROBIN Joel Schumacher 20008 CONTACT Robert Zemeckis 20009 BODYGUARD Mick Jackson 20010 COP LAND James Mangold 20011 PELICAN BRIEF,THE Alan J.Pakula 20012 KLIENT, DER Joel Schumacher 20013 ADDICTED TO LOVE Griffin Dunne 20014 ARMAGEDDON Michael Bay 20015 SPACE JAM Joe Pytka 20016 CONAIR Simon West 20017 HORSE WHISPERER,THE Robert Redford 20018 LETHAL WEAPON 4 Richard Donner 20019 LION KING 2 20020 ROCKY HORROR PICTURE SHOW Jim Sharman 20021 X‐FILES 20022 GATTACA Andrew Niccol 20023 STARSHIP TROOPERS Paul Verhoeven 20024 YOU'VE GOT MAIL Nora Ephron 20025 NET,THE Irwin Winkler 20026 RED CORNER Jon Avnet 20027 WILD WILD WEST Barry Sonnenfeld 20028 EYES WIDE SHUT Stanley Kubrick 20029 ENEMY OF THE STATE Tony Scott 20030 LIAR,LIAR/Der Dummschwätzer Tom Shadyac 20031 MATRIX Wachowski Brothers 20032 AUF DER FLUCHT Andrew Davis 20033 TRUMAN SHOW, THE Peter Weir 20034 IRON GIANT,THE 20035 OUT OF SIGHT Steven Soderbergh 20036 SOMETHING ABOUT MARY Bobby &Peter Farrelly 20037 TITANIC James Cameron 20038 RUNAWAY BRIDE Garry Marshall 20039 NOTTING HILL Roger Michell 20040 TWISTER Jan DeBont 20041 PATCH ADAMS Tom Shadyac 20042 PLEASANTVILLE Gary Ross 20043 FIGHT CLUB, THE David -

Bennett V. Spear and the Past and Future of Standing in Environmental Cases

STANDING ON ITS LAST LEGS: BENNETT V. SPEAR AND THE PAST AND FUTURE OF STANDING IN ENVIRONMENTAL CASES STANDING ON ITS LAST LEGS: BENNETT V. SPEAR AND THE PAST AND FUTURE OF STANDING IN ENVIRONMENTAL CASES SAM KALEN[*] Copyright © 1997 Florida State University Journal of Land Use & Environmental Law No man is an IIand, intire of itselfe; every man is a peece of the Continent, a part of the maine; if a Clod bee washed away by the Sea, Europe is the lesse, as well as if a Promontorie were, as well as if a Mannor of thy friends or of thine owne were; any man's death diminishes me, because I am involved in Mankinde; And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.[1] BLOCKQUOTE> I. INTRODUCTION The law of "standing" in environmental disputes appears to be resting on its last legs, and well it should be. Arguably, standing's fate has been sealed since its conception in the 1970s.[2] Now, approximately a quarter of a century later, standing is on the verge of collapsing onto its weak intellectual foundation. The standing doctrine is that part of the "law of judicial jurisdiction" that "determines whom a court may hear make arguments about the legality of an official decision."[3] Almost twenty years ago, Joseph Vining viewed standing with "a sense of intellectual crisis."[4] In the years since, that intellectual crisis has grown. The Supreme Court's recent decision in Bennett v. Spear[5] reflects one aspect of how this crisis has become too unwieldy. -

Hoi Polloi, 1989

SHELVED IN BOUND PERIODICALS ------------ -----· ---- hoi polloi* Staff Stacey Alexander Terry Hulsey Angie Roberts Faculty Advisors Thomas J. Sauret William Bradley Strickland V.l Il l •HOY-po-LOY: noun. 1. The common masses; the man in the street; the average person; the herd. 2. A literary publication of Gainesville College, comprised of nonfiction essays. Copy1ight 1989 by the Humanities Division of Gnincsvillc College. At> 2 \ t:...i 1 This publication consists of essays written by 'w'lq9~ e, ,f Gainesville College students. I hope that this slim vol ume of student writing helps illustrate what is right with Gainesville College. It clearly reflects the fact that the hoi polloi college attracts insightful, talented, a~ intelluctually curious students who take the time and effort to do more than what is required of them in a classroom. Only three of these essays were written as asignments for a writing course . This first Hoi Polloi attests that there is a place Table ofContents on campus for students who want more than a "drive through" education. All except one of these essays went through revisions and have been changed significantly by Wonderful Male Species.. ............................................. 3 the authors. These writers did not work for a grade; they By Diane Wall worked at the writing because they truly had something to say and they wanted to say it well. The Youth Syndrome.. ................................................5 By Stacey Alexander Hoi Polloi is a collection of the best non-fiction essays written at the College over the past year. The three Autumn............ ............................................................!! winners of the Gainesville College Writing Contest are By Teresa Smith included here. -

C Asper the Friendly Ghost Jumpchain

C asper The Friendly Ghost Jumpchain Welcome to the Worlds of Casper the Friendly Ghost... Alive or dead you'll be spending the next ten years dwelling here. The Worlds of Casper have one common theme, ghosts should be scary; those that won't be mean, will be disciplined. Here, Have 1000 Casper Points to get you started. Location To start off roll 1d8 to determine your location or pay 50cp to choose 1. 1950's Animated Casper – Noveltoons/HarveyToons. - This is the world of the original Casper cartoons, Casper 'lives' with his three 'Uncles' the Terrible Trio; Fatso, Fusso, and Lazo pressure poor Casper into being mean when he just want's to make friends. You may be able to make friends with the family of Richie Rich while you are here. 2. 1960's New Casper Cartoon Show – Casper and his friends, the ghost horse Nightmare, and Wendy the Good Little Witch, are all somewhat ostracized by their peers as they just want to be nice. This world features many elements from classic fantasy, enchanted forests, A Toyland, even Alien visitors. 3. 1970's Casper TV Specials by Hanna-Barbera - Casper Celebrated Both Halloween and Christmas with the Hanna-Barbera Gang. Yogi Bear, Snagglepuss, Huckleberry Hound et cetra. Why not visit Jellystone park while you're here? 4. 1990's Casper Film/The Spooktacular New Adventures of Casper series - This is the only version of Casper to have a Human Life to be remembered. C. McFadden is the son of a mysterious inventor and owner of Whipstaff Manor. -

The New School, Everybody Comes to Rick's

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model or to indicate particular areas that are of interest to the Endowment, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects his or her unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the Research Programs application guidelines at https://www.neh.gov/grants/research/public- scholar-program for instructions. Formatting requirements, including page limits, may have changed since this application was submitted. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Research Programs staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: Everybody Comes to Rick’s: How “Casablanca” Taught Us to Love Movies Institution: The New School Project Director: Noah Isenberg Grant Program: Public Scholar Program 400 Seventh Street, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8200 F 202.606.8204 E [email protected] www.neh.gov Everybody Comes to Rick’s: How Casablanca Taught Us to Love Movies On Thanksgiving Day 1942, the lucky ticket holders who filled the vast, opulent 1,600-seat auditorium at Warner Brothers’ Hollywood Theatre in midtown Manhattan—where today the Times Square Church stands—were treated to the world premiere of Casablanca, the studio’s highly anticipated wartime drama. -

Pdf, 742.59 KB

00:00:00 Dan McCoy Host On this episode, we discuss: Doolittle! 00:00:03 Stuart Host Why do they call him “Do little”? I think he does a lot in this movie! Wellington [Laughs.] 00:00:08 Elliott Kalan Host The—Stu, that’s exactly what I was gonna say. 00:00:11 Dan Host And it was what Audrey predicted was gonna be the gag. [Multiple people laugh.] 00:00:15 Elliott Host That is the exact thing I have written in my notes to say, Stu, for this—for this part. Ah. Two peas in a pod. 00:00:22 Music Music Light, up-tempo, electric guitar with synth instruments. 00:00:49 Dan Host Hey, everyone, and welcome to The Flop House. I’m Dan McCoy. 00:00:52 Stuart Host Oh hey there! I’m Stuart Wellington. 00:00:54 Elliott Host Top o’ the morning! Or whenever you’re listening to this—midnight? I don’t know! I’m Elliott Kalan. And Dan, who’s joining us? 00:01:01 Crosstalk Crosstalk Stuart: Yeah, Dan. Elliott: Or Stuart. 00:01:02 Dan Host Uh… 00:01:03 Elliott Host Or Dan. 00:01:04 Crosstalk Crosstalk Elliott: Or Stuart? Dan: I thought we decided on Stuart— 00:01:05 Dan Host —but I can say it. It’s—it’s David Sims, of the Blank Check podcast and he is the, uh… film reviewer for The Atlantic. And that is a—that is a big, high-toned magazine. That is, uh, that is a respected publication. -

MEMORY of the WORLD REGISTER the Wizard of Oz

MEMORY OF THE WORLD REGISTER The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming 1939), produced by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer REF N° 2006-10 PART A – ESSENTIAL INFORMATION 1 SUMMARY In 1939, as the world fell into the chaos of war, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer released a film that espoused kindness, charity, friendship, courage, fortitude, love and generosity. It was dedicated to the “young, and the young in heart” and today it remains one of the most beloved works of cinema, embraced by audiences of all ages throughout the world. It is one of the most widely seen and influential films in all of cinema history. The Wizard of Oz (1939) has become a true cinema classic, one that resonates with hope and love every time Dorothy Gale (the inimitable Judy Garland in her signature screen performance) wistfully sings “Over the Rainbow” as she yearns for a place where “troubles melt like lemon drops” and the sky is always blue. George Eastman House takes pride in nominating The Wizard of Oz for inclusion in the Memory of the World Register because as custodian of the original Technicolor 3-strip nitrate negatives and the black and white sequences preservation negatives and soundtrack, the Museum has conserved these precious artefacts, thus ensuring the survival of this film for future generations. Working in partnership with the current legal owner, Warner Bros., the Museum has made it possible for this beloved film classic to continue to enchant and delight audiences. The original YCM negatives have been conserved at the Museum since 1975, and Warner Bros. recently completed our holdings of the film by assigning the best surviving preservation elements of the opening and closing black and white sequences and the soundtrack to our care. -

Jigsaw: Torture Porn Rebooted? Steve Jones After a Seven-Year Hiatus

Originally published in: Bacon, S. (ed.) Horror: A Companion. Oxford: Peter Lang, 2019. This version © Steve Jones 2018 Jigsaw: Torture Porn Rebooted? Steve Jones After a seven-year hiatus, ‘just when you thought it was safe to go back to the cinema for Halloween’ (Croot 2017), the Saw franchise returned. Critics overwhelming disapproved of franchise’s reinvigoration, and much of that dissention centred around a label that is synonymous with Saw: ‘torture porn’. Numerous critics pegged the original Saw (2004) as torture porn’s prototype (see Lidz 2009, Canberra Times 2008). Accordingly, critics such as Lee (2017) characterised Jigsaw’s release as heralding an unwelcome ‘torture porn comeback’. This chapter will investigate the legitimacy of this concern in order to determine what ‘torture porn’ is and means in the Jigsaw era. ‘Torture porn’ originates in press discourse. The term was coined by David Edelstein (2006), but its implied meanings were entrenched by its proliferation within journalistic film criticism (for a detailed discussion of the label’s development and its implied meanings, see Jones 2013). On examining the films brought together within the press discourse, it becomes apparent that ‘torture porn’ is applied to narratives made after 2003 that centralise abduction, imprisonment, and torture. These films focus on protagonists’ fear and/or pain, encoding the latter in a manner that seeks to ‘inspire trepidation, tension, or revulsion for the audience’ (Jones 2013, 8). The press discourse was not principally designed to delineate a subgenre however. Rather, it allowed critics to disparage popular horror movies. Torture porn films – according to their detractors – are comprised of violence without sufficient narrative or character development (see McCartney 2007, Slotek 2009). -

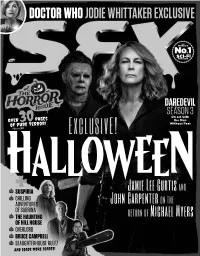

SFX’S Horror Columnist Peers Into If You’Re New to the Netflix Catherine Zeta-Jones Movie

DOCTOR WHO JODIE WHITTAKER EXCLUSIVE SCI-FI 306 DAREDEVIL SEASON 3 On set with Over 30 pages the Man of pure terror! Without Fear featuring EXCLUSIVE! HALLOWEEN Jamie Lee Curtis and SUSPIRIA CHILLING John Carpenter on the ADVENTURES OF SABRINA return of Michael Myers THE HAUNTING OF HILL HOUSE OVERLORD BRUCE CAMPBELL SLAUGHTERHOUSE RULEZ AND LOADS MORE SCARES! ISSUE 306 NOVEMBER Contents2018 34 56 61 68 HALLOWEEN CHILLING DRACUL DOCTOR WHO Jamie Lee Curtis and John ADVENTURES Bram Stoker’s great-grandson We speak to the new Time Lord Carpenter tell us about new OF SABRINA unearths the iconic vamp for Jodie Whittaker about series 11 Michael Myers sightings in Remember Melissa Joan Hart another toothsome tale. and her Heroes & Inspirations. Haddonfield. That place really playing the teenage witch on CITV needs a Neighbourhood Watch. in the ’90s? Well this version is And a can of pepper spray. nothing like that. 62 74 OVERLORD TADE THOMPSON A WW2 zombie horror from the The award-winning Rosewater 48 56 JJ Abrams stable and it’s not a author tells us all about his THE HAUNTING OF Cloverfield movie? brilliant Nigeria-set novel. HILL HOUSE Shirley Jackson’s horror classic gets a new Netflix treatment. 66 76 Who knows, it might just be better PENNY DREADFUL DAREDEVIL than the 1999 Liam Neeson/ SFX’s horror columnist peers into If you’re new to the Netflix Catherine Zeta-Jones movie. her crystal ball to pick out the superhero shows, this third season Fingers crossed! hottest upcoming scares. is probably a bad place to start. -

Human' Jaspects of Aaonsí F*Oshv ÍK\ Tke Pilrns Ana /Movéis ÍK\ É^ of the 1980S and 1990S

DOCTORAL Sara MarHn .Alegre -Human than "Human' jAspects of AAonsí F*osHv ÍK\ tke Pilrns ana /Movéis ÍK\ é^ of the 1980s and 1990s Dirigida per: Dr. Departement de Pilologia jA^glesa i de oermanisfica/ T-acwIfat de Uetres/ AUTÓNOMA D^ BARCELONA/ Bellaterra, 1990. - Aldiss, Brian. BilBon Year Spree. London: Corgi, 1973. - Aldridge, Alexandra. 77» Scientific World View in Dystopia. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1978 (1984). - Alexander, Garth. "Hollywood Dream Turns to Nightmare for Sony", in 77» Sunday Times, 20 November 1994, section 2 Business: 7. - Amis, Martin. 77» Moronic Inferno (1986). HarmorKlsworth: Penguin, 1987. - Andrews, Nigel. "Nightmares and Nasties" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984:39 - 47. - Ashley, Bob. 77» Study of Popidar Fiction: A Source Book. London: Pinter Publishers, 1989. - Attebery, Brian. Strategies of Fantasy. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1992. - Bahar, Saba. "Monstrosity, Historicity and Frankenstein" in 77» European English Messenger, vol. IV, no. 2, Autumn 1995:12 -15. - Baldick, Chris. In Frankenstein's Shadow: Myth, Monstrosity, and Nineteenth-Century Writing. Oxford: Oxford Clarendon Press, 1987. - Baring, Anne and Cashford, Jutes. 77» Myth of the Goddess: Evolution of an Image (1991). Harmondsworth: Penguin - Arkana, 1993. - Barker, Martin. 'Introduction" to Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Media. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984(a): 1-6. "Nasties': Problems of Identification" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney. Ruto Press, 1984(b): 104 - 118. »Nasty Politics or Video Nasties?' in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Medß. -

Ancient Tragedy, Echoed by a Chorus of Veterans - the New York Times

The Lunatic Is on the Air: A Stoppard Radio Play for Pink Floyd's 'Dark Side of the Moon' - NYTimes.com MARCH 28, 2013, 8:51 AM The Lunatic Is on the Air: A Stoppard Radio Play for Pink Floyd’s ‘Dark Side of the Moon’ By DAVE ITZKOFF The 40th anniversary of the release of “The Dark Side of the Moon,” that best-selling Pink Floyd album, technically occurred earlier this month. But in the case of a seminal prog-rock record that deals with the nature of time (and the slowing-down thereof), we’ll forgive Tom Stoppard if his unique effort to celebrate this milestone doesn’t actually arrive until the summer. Mr. Stoppard, the celebrated playwright of “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead” and “The Coast of Utopia” and a screenwriter of “Shakespeare in Love,” among many other works, has written a new play for British radio that will mark the 40 years since “The Dark Side of the Moon” was released in March 1973, The Guardian reported. But this latest dramatic work is no simple narrative of how Roger Waters, David Gilmour and company spent several months at Abbey Road recording songs like “Money,” “Time” and “Breathe.” This one’s … a little weird. Describing Mr. Stoppard’s radio play, called “Dark Side,” at its Web site, the BBC called it “a fantastical and psychedelic story based on themes from the seminal album” that incorporates “music from the album and a gripping story that takes listeners on a journey through their imaginations.” (So keep your black-light posters handy, apparently.) Mr. -

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List # 20 Wild Westerns: Marshals & Gunman 2 Days in the Valley (2 Discs) 2 Family Movies: Family Time: Adventures 24 Season 1 (7 Discs) of Gallant Bess & The Pied Piper of 24 Season 2 (7 Discs) Hamelin 24 Season 3 (7 Discs) 3:10 to Yuma 24 Season 4 (7 Discs) 30 Minutes or Less 24 Season 5 (7 Discs) 300 24 Season 6 (7 Discs) 3-Way 24 Season 7 (6 Discs) 4 Cult Horror Movies (2 Discs) 24 Season 8 (6 Discs) 4 Film Favorites: The Matrix Collection- 24: Redemption 2 Discs (4 Discs) 27 Dresses 4 Movies With Soul 40 Year Old Virgin, The 400 Years of the Telescope 50 Icons of Comedy 5 Action Movies 150 Cartoon Classics (4 Discs) 5 Great Movies Rated G 1917 5th Wave, The 1961 U.S. Figure Skating Championships 6 Family Movies (2 Discs) 8 Family Movies (2 Discs) A 8 Mile A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2 Discs) 10 Bible Stories for the Whole Family A.R.C.H.I.E. 10 Minute Solution: Pilates Abandon 10 Movie Adventure Pack (2 Discs) Abduction 10,000 BC About Schmidt 102 Minutes That Changed America Abraham Lincoln Vampire Hunter 10th Kingdom, The (3 Discs) Absolute Power 11:14 Accountant, The 12 Angry Men Act of Valor 12 Years a Slave Action Films (2 Discs) 13 Ghosts of Scooby-Doo, The: The Action Pack Volume 6 complete series (2 Discs) Addams Family, The 13 Hours Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter 13 Towns of Huron County, The: A 150 Year Brother, The Heritage Adventures in Babysitting 16 Blocks Adventures in Zambezia 17th Annual Lane Automotive Car Show Adventures of Dally & Spanky 2005 Adventures of Elmo in Grouchland, The 20 Movie Star Films Adventures of Huck Finn, The Hartford Public Library DVD Title List Adventures of Ichabod and Mr.