Cyprus Before the Bronze Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CYPRUS Cyprus in Your Heart

CYPRUS Cyprus in your Heart Life is the Journey That You Make It It is often said that life is not only what you are given, but what you make of it. In the beautiful Mediterranean island of Cyprus, its warm inhabitants have truly taken the motto to heart. Whether it’s an elderly man who basks under the shade of a leafy lemon tree passionately playing a game of backgammon with his best friend in the village square, or a mother who busies herself making a range of homemade delicacies for the entire family to enjoy, passion and lust for life are experienced at every turn. And when glimpsing around a hidden corner, you can always expect the unexpected. Colourful orange groves surround stunning ancient ruins, rugged cliffs embrace idyllic calm turquoise waters, and shady pine covered mountains are brought to life with clusters of stone built villages begging to be explored. Amidst the wide diversity of cultural and natural heritage is a burgeoning cosmopolitan life boasting towns where glamorous restaurants sit side by side trendy boutiques, as winding old streets dotted with quaint taverns give way to contemporary galleries or artistic cafes. Sit down to take in all the splendour and you’ll be made to feel right at home as the locals warmly entice you to join their world where every visitor is made to feel like one of their own. 2 Beachside Splendour Meets Countryside Bliss Lovers of the Mediterranean often flock to the island of Aphrodite to catch their breath in a place where time stands still amidst the beauty of nature. -

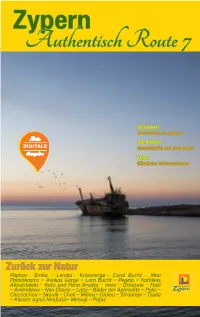

Zypern Authentisch Route 7

Zypern Authentisch Route 7 Sicherheit Autofahren in Zypern Nur Gemütliche DIGITALE Unterkünfte auf dem Land Ausgabe Tipps Nützliche Informationen Zurück zur Natur Paphos – Emba – Lemba – Kissonerga – Coral Bucht – Maa Palaiokastro – Avakas Gorge – Lara Bucht – Pegeia – Kathikas Akourdaleia – Kato und Pano Arodes – Ineia – Drouseia – Fasli – Androlikou – Neo Chorio – Latsi – Bäder der Aphrodite – Polis – Chrysochou – Skoulli – Choli – Miliou – Giolou – Stroumpi – Tsada – Kloster Agios Neofytos– Mesogi – Pafos Route 7 Paphos – Emba – Lemba – Kissonerga – Coral Bucht – Maa Palaiokastro – Avakas Gorge – Lara Bucht – Pegeia – Kathikas Akourdaleia – Kato und Pano Arodes – Ineia – Drouseia – Fasli – Androlikou – Neo Chorio – Latsi – Bäder der Aphrodite – Polis – Chrysochou – Skoulli – Choli – Miliou – Giolou – Stroumpi – Tsada – Kloster Agios Neofytos– Mesogi – Pafos Agia Marina Mazaki Islet T I L L I R I A Cape Arnaoutis Livadi (Akamas) CHRYSOCHOU BAY Gialia Ε4 Agios Georgios Islet Argaka Ryrgos tis Rigenas (Ruins) Makounta Loutra tis Marion Aphroditis (Baths Argaka of Aphrodite) Polis Kynousa Kioni Islet Neo Pelathousa Agios Chorio Stavros A Minas Agios tis Chrysochou K Isidoros Psokas Androlikou Karamoullides Lysos A Steni Goudi Peristerona M Melandra Fasli Meladeia Choli Skoulli Zacharia Agia AikaterinTirimithousa A Kios Drouseia Tera Church Filousa Kritou (15th cent) S Ineia Tera Kato Evretou Lara Sarama Akourdaleia Loukrounou Anadiou Simou Kato Arodes Pano Miliou Kannaviou Fyti Dam Gorge Pano Akourdaleia akas Drymou Lasa Kritou Av Arodes -

Timeline from Ice Ages to European Arrival in New England

TIMELINE FROM ICE AGES TO EUROPEAN ARRIVAL IN NEW ENGLAND Mitchell T. Mulholland & Kit Curran Department of Anthropology, University of Massachusetts Amherst 500 Years Before Present CONTACT Europeans Arrive PERIOD 3,000 YBP WOODLAND Semi-permanent villages in which cultivated food crops are stored. Mixed-oak forest, chestnut. Slash and burn agriculture changes appearance of landscape. Cultivated plants: corn, beans, and squash. Bows and arrows, spears used along with more wood, bone tools. 6,000 YBP LATE Larger base camps; small groups move seasonally ARCHAIC through mixed-oak forest, including some tropical plants. Abundant fish and game; seeds and nuts. 9,000 YBP EARLY & Hunter/gatherers using seasonal camping sites for MIDDLE several months duration to hunt deer, turkey, ARCHAIC and fish with spears as well as gathering plants. 12,000 YBP PALEOINDIAN Small nomadic hunting groups using spears to hunt caribou and mammoth in the tundra Traditional discussions of the occupation of New England by prehistoric peoples divide prehistory into three major periods: Paleoindian, Archaic and Woodland. Paleoindian Period (12,000-9,000 BP) The Paleoindian Period extended from approximately 12,000 years before present (BP) until 9,000 BP. During this era, people manufactured fluted projectile points. They hunted caribou as well as smaller animals found in the sparse, tundra-like environment. In other parts of the country, Paleoindian groups hunted larger Pleistocene mammals such as mastodon or mammoth. In New England there is no evidence that these mammals were utilized by humans as a food source. People moved into New England after deglaciation of the region concluded around 14,000 BP. -

Living Quarters, Households, Institutions and Population Enumerated by District, Municipality/Community and Quarter (1.10.2011)

LIVING QUARTERS, HOUSEHOLDS, INSTITUTIONS AND POPULATION ENUMERATED BY DISTRICT, MUNICIPALITY/COMMUNITY AND QUARTER (1.10.2011) LIVING QUARTERS HOUSEHOLDS INSTITUTIONS DISTRICT, GEO/CAL Vacant/ Of TOTAL MUNICIPALITY/COMMUNITY Of usual CODE Total temporary NumberPopulationNumberPopulation POPULATION AND QUARTER residence residence (1) Total 433,212 299,275 133,937 303,242 836,566 211 3,841 840,407 1 Lefkosia District 144,556 117,280 27,276 119,203 324,952 94 2,028 326,980 1000 Lefkosia Municipality 28,298 22,071 6,227 22,833 54,452 11 562 55,014 100001 Agios Andreas 2,750 2,157 593 2,206 5,397 4 370 5,767 100002 Trypiotis 1,293 949 344 1,009 2,158 2,158 100003 Nempetchane 109 80 29 93 189 189 100004 Tampakchane 177 133 44 159 299 299 100005 Faneromeni 296 228 68 264 512 512 100006 Agios Savvas 308 272 36 303 581 581 100007 Omerie 93 81 12 106 206 206 100008 Agios Antonios 3,231 2,485 746 2,603 5,740 2 61 5,801 100009 Agios Ioannis 114 101 13 111 216 1 5 221 100010 Taktelkale 369 317 52 332 814 1 12 826 100011 Chrysaliniotissa 71 56 15 58 124 124 100012 Agios Kassianos 49 28 21 28 82 82 100013 Kaïmakli 5,058 4,210 848 4,250 11,475 2 89 11,564 100014 Panagia 6,211 4,818 1,393 4,883 12,398 12,398 100015 Agioi Konstantinos kai Eleni 1,939 1,331 608 1,350 3,209 3,209 100016 Agioi Omologitai 5,971 4,609 1,362 4,855 10,503 1 25 10,528 100017 Arap Achmet 28 18 10 18 50 50 100018 Geni Tzami 114 93 21 98 215 215 100019 Omorfita 117 105 12 107 284 284 1010 Agios Dometios Municipality 5,825 4,824 1,001 4,931 12,395 4 61 12,456 101001 Agios Pavlos 1,414 -

Athens (-34% Vs

COVID-19 Impact on EUROCONTROL Airports EUROCONTROL Airport Briefings 9 July 2021 Total flights lost since 1 March 2020: 165,580 flights Current flight status: 641 daily flights or -23% vs 2019 (7-day average)1 Current ranking: 8th Busiest airline: Aegean Airlines:253 average daily flights1 (-29% vs. 2019) Busiest destination country: Greece with 151 average daily flights1 (-16% vs. 2019) Busiest destination airport: Santorini with 17 average daily flights1 Athens (-34% vs. 2019) Similar levels for international traffic (-27% vs 2019) and internal traffic (-17% vs 2019) with traditional scheduled airlines 2020/21 Traffic Evolution Athens Traffic variation (7-day average number of flights) 900 800 700 600 500 400 300 200 100 0 25 Jul25 04 Jul 11 Jul 18 Jul 03 Jan 10 Jan 17 Jan 24 Jan 31 Jan 06 Jun 13 Jun 20 Jun 27 Jun 24 Oct 24 03 Oct 10 Oct 17 Oct 31 Oct 04 Apr 11 Apr 18 Apr 25 Apr 21 Feb21 07 Feb 14 Feb 28 Feb 05 Sep 12 Sep 19 Sep 26 Sep 26 Dec26 05 Dec 12 Dec 19 Dec 01 Aug 08 Aug 15 Aug 22 Aug 29 Aug 07 Nov 14 Nov 21 Nov 28 Nov 07 Mar 14 Mar 21 Mar 28 Mar 02 May 09 May 16 May 23 May 30 May 2021 2020 2019 7-day average 7-day average 7-day average Athens Change in number of flights from the same day of the previous week Increase Decrease 7-day flight average +109 660 640 +87 +79 620 +65 +66 600 +54 +48 580 +36 +33 +32 +24 +25 560 +3 540 520 -1 500 Fri 25 Sat 26 Sun 27 Mon 28 Tue 29 Wed 30 Thu 01 Fri 02 Jul Sat 03 Sun 04 Mon 05 Tue 06 Wed 07 Thu 08 Jun Jun Jun Jun Jun Jun Jul Jul Jul Jul Jul Jul Jul COVID-19 Impact on EUROCONTROL Airports EUROCONTROL Airport Briefings 9 July 2021 Traffic Composition Rank Flights (arr+dep) Actual vs prev. -

On the Nature of Transitions: the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic and the Neolithic Revolution

On the Nature of Transitions: the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic and the Neolithic Revolution The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Bar-Yosef, Ofer. 1998. “On the Nature of Transitions: The Middle to Upper Palaeolithic and the Neolithic Revolution.” Cam. Arch. Jnl 8 (02) (October): 141. Published Version doi:10.1017/S0959774300000986 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12211496 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Cambridge Archaeological Journal 8:2 (1998), 141-63 On the Nature of Transitions: the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic and the Neolithic Revolution Ofer Bar-Yosef This article discusses two major revolutions in the history of humankind, namely, the Neolithic and the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic revolutions. The course of the first one is used as a general analogy to study the second, and the older one. This approach puts aside the issue of biological differences among the human fossils, and concentrates solely on the cultural and technological innovations. It also demonstrates that issues that are common- place to the study of the trajisition from foraging to cultivation and animal husbandry can be employed as an overarching model for the study of the transition from the Middle to the Upper Palaeolithic. The advantage of this approach is that it focuses on the core areas where each of these revolutions began, the ensuing dispersals and their geographic contexts. -

The Vernacular in Church Architecture

Le Corbusier’s pilgrimage chapel at Ronchamp, France. Photo: Groucho / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 / https://www.flickr. com/photos/grou- cho/13556662883 LIVING STONES The Vernacular in Church Architecture Alexis Vinogradov 1 Gregory Dix, The The liturgy of the Early Christian era the heart of worship that is ultimately Shape of the Lit- was about doing rather than saying. to be expressed and enhanced by both urgy (Westminster: Dacre Press, 1945), This distinction is borrowed from Dom art and architecture. Of course this con- 12–15. Kiprian Kern, Gregory Dix by Fr. Kyprian Kern, who sideration must include literature, mu- Евхаристия (Paris: was responsible for the first major Or- sic, and ritual movement and gesture. YMCA-Press, 1947). thodox investigation of the sources 2 and practices of the Christian eccle- Our earliest archaeological discover- Marcel Jousse, L’An- 1 thropologie du geste sia. The Jesuit scholar Marcel Jousse ies substantiate the nature of the “do- (Paris: Gallimard, reinforces this assertion in writing of ing” performed by the Church. The 2008). the early Christian practice and un- celebrants did not initially constitute derstanding of “eating and drinking” a distinct caste, for all who were gath- the word, rooted in a mimesis of ges- ered were involved in the rites. One tures passed on through generations.2 can therefore understand the emer- “Do this in remembrance of me,” says gence throughout Christian history of Christ at the last gathering with his anti-clerical movements, which have disciples (Lk. 22:19). pushed back against the progressive exclusion of the faithful from areas The present essay is about the ver- deemed “sacred” in relation to the nacular in church architecture. -

Informazioni Nautiche Ed Avvisi Ntm Iii

I.I. 3146 ISTITUTO IDROGRAFICO DELLA MARINA INFORMAZIONI NAUTICHE ED AVVISI NTM III RACCOLTA SEMESTRALE N. 1/2019 (Situazione aggiornata al Fascicolo Avvisi ai Naviganti n° 26/2018 compreso) SUPPLEMENTO AL QUINDICINALE AVVISI AI NAVIGANTI N° 1/19 DEL 02/01/2019 Tariffa Regime Libero Poste Italiane S.p.A. Spedizione in Abbonamento 70% - DCB Genova ANNULLA LA PRECEDENTE EDIZIONE QUESTO FASCICOLO DEVE ESSERE SEMPRE TENUTO PRESENTE DURANTE LA CONSULTAZIONE DEI DOCUMENTI NAUTICI USATI PER LA NAVIGAZIONE (Carte, Portolani, Elenco Fari, Radioservizi, ecc.). Genova 2019 I.I. 3146 ISTITUTO IDROGRAFICO DELLA MARINA INFORMAZIONI NAUTICHE ED AVVISI NTM III RACCOLTA SEMESTRALE N. 1/2019 (Situazione aggiornata al Fascicolo Avvisi ai Naviganti n° 26/2018 compreso) SUPPLEMENTO AL QUINDICINALE AVVISI AI NAVIGANTI N° 1/19 DEL 02/01/2019 Tariffa Regime Libero Poste Italiane S.p.A. Spedizione in Abbonamento 70% - DCB Genova ANNULLA LA PRECEDENTE EDIZIONE QUESTO FASCICOLO DEVE ESSERE SEMPRE TENUTO PRESENTE DURANTE LA CONSULTAZIONE DEI DOCUMENTI NAUTICI USATI PER LA NAVIGAZIONE (Carte, Portolani, Elenco Fari, Radioservizi, ecc.). Genova 2019 La presente Raccolta deve essere tenuta aggiornata applicando, in ultima pagina, la sezione C del fascicolo “Avvisi ai Naviganti”, dove saranno riportate: . i numeri distintivi delle Informazioni Nautiche annullate . il riepilogo dei numeri distintivi delle Informazioni Nautiche in vigore suddivise per zona . le nuove Informazioni Nautiche con il relativo numero distintivo . i numeri distintivi degli Avvisi NTM III annullati . il riepilogo dei numeri distintivi degli Avvisi NTM III in vigore . i nuovi Avvisi NTM III con i relativi numeri distintivi © Copyright, I.I.M. Genova 2019 Istituto Idrografico della Marina Passo Osservatorio, 4 – Telefono: 01024431 PEC: [email protected] PEI: [email protected] Sito: www.marina.difesa.it “Documento Ufficiale dello Stato (Legge 2.2.1960 N. -

Architecture As Urban Practice in Contested Spaces

Intro Socrates Stratis Architecture as Urban Practice in Contested Spaces Introduction Through this essay we will look into the challenge of architecture to support the city commons in contested spaces by establishing relations between modes of reconciliation and processes of urban regeneration. To address such challenge, we need to look into architecture as urban practice, recognizing its inherent non-conflict-free interventional character. Architecture as urban practice in contested spaces has a hybrid character, since its agencies, modes of action, as well as its pedagogical stance, emerge thanks to a tactful synergy across material practices, such as architecture, urban design, planning, visual arts, and Information and Communication Technology. The moving project lies in the heart of architecture as urban practice, since the process of making, the agencies of the materiality of such a process, as well as the emergent actorial relations, get a prominent role. Modes of reconciliation are embedded deep into the making of by establishing platforms of exchange of designerly knowledge to support the project actors’ negotiations, and even change their conflictual postures, especially in contested spaces. By contributing to the city commons, The essay consists of three parts. Firstly, architecture as urban practice may provide we will situate architecture in different alternatives, both to dominant divisive kinds of contested spaces and show how, urban narratives and to the neoliberal urban by withdrawing from the political, it is reconstruction paradigm. The “Hands-on indirectly caught in consolidating politics Famagusta” project, which is the protagonist of division. We will, then, focus on an of this Guide to Common Urban Imaginaries agonistic approach of architecture as practice in Contested Spaces, contributes to such by unpacking its agencies, modes of action, approach, supporting the urban peace- and pedagogies. -

Authentic Cyprus - Depliant.Pdf

Thanks to its year-round sunshine, blue skies and warm waters, Cyprus enjoys an enviable reputation as one of the world’s top sun, sea and sand holiday destinations. But this delightful island has much more to offer. Away from the tourist areas, the Cyprus countryside has a diverse wealth all of its own, including traditional villages, vineyards and wineries, tiny fresco-painted churches, remote monasteries and cool shady forests. This is a nature-lovers paradise, where you can walk for hours without seeing another living soul. In springtime, fields of flowers stretch as far as the eye can see, and a ramble along a mountain path will suddenly reveal a tiny Byzantine chapel or a Venetian-built bridge that once formed part of an ancient trade route. Around every corner is another surprise; a magnificent view; a rare sighting of the Cyprus moufflon; or a chance encounter with someone who will surprise you with their knowledge of your language and an invitation to join the family for a coffee. In the villages, traditional values remain, while the true character of the Cypriot people shines through wherever you go - warm-hearted, friendly, family-orientated, and unbelievably hospitable. Around 1200BC, the arrival of Greek-speaking settlers caused great disruption and led to the emergence of the first of the city kingdoms of the Iron Age. The influence of Greek culture rapidly Throughout the following centuries became evident in every of foreign domination, everyday life in the aspect of Cypriot life. more remote rural villages hardly changed Cultural until the beginning of the 20th century, During the Hellenistic period when electricity and motorised transport (4th century BC), copper mining was arrived and the first paved roads were generating such wealth that Cyprus constructed. -

The History of the Wheel and Bicycles

NOW & THE FUTURE THE HISTORY OF THE WHEEL AND BICYCLES COMPILED BY HOWIE BAUM OUT OF THE 3 BEST INVENTIONS IN HISTORY, ONE OF THEM IS THE WHEEL !! Evidence indicates the wheel was created to serve as potter's wheels around 4300 – 4000 BCE in Mesopotamia. This was 300 years before they were used for chariots. (Jim Vecchi / Corbis) METHODS TO MOVE HEAVY OBJECTS BEFORE THE WHEEL WAS INVENTED Heavy objects could be moved easier if something round, like a log was placed under it and the object rolled over it. The Sledge Logs or sticks were placed under an object and used to drag the heavy object, like a sled and a wedge put together. Log Roller Later, humans thought to use the round logs and a sledge together. Humans used several logs or rollers in a row, dragging the sledge over one roller to the next. Inventing a Primitive Axle With time, the sledges started to wear grooves into the rollers and humans noticed that the grooved rollers actually worked better, carrying the object further. The log roller was becoming a wheel, humans cut away the wood between the two inner grooves to create what is called an axle. THE ANCIENT GREEKS INVENTED WESTERN PHILOSOPHY…AND THE WHEELBARROW CHINA FOLLOWED 400 YEARS AFTERWARDS The wheelbarrow first appeared in Greece, between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE. It was found in China 400 years later and then ended up in medieval Europe. Although wheelbarrows were expensive to purchase, they could pay for themselves in just 3 or 4 days in terms of labor savings. -

Download Download

BORN IN THE MEDITERRANEAN: Alicia Vicente,3 Ma Angeles´ Alonso,3 and COMPREHENSIVE TAXONOMIC Manuel B. Crespo3* REVISION OF BISCUTELLA SER. BISCUTELLA (BRASSICACEAE) BASED ON MORPHOLOGICAL AND PHYLOGENETIC DATA1,2 ABSTRACT Biscutella L. ser. Biscutella (5 Biscutella ser. Lyratae Malin.) comprises mostly annual or short-lived perennial plants occurring in the Mediterranean basin and the Middle East, which exhibit some diagnostic floral features. Taxa in the series have considerable morphological plasticity, which is not well correlated with clear geographic or ecologic patterns. Traditional taxonomic accounts have focused on a number of vegetative and floral characters that have proved to be highly variable, a fact that contributed to taxonomic inflation mostly in northern Africa. A detailed study and re-evaluation of morphological characters, together with recent phylogenetic data based on concatenation of two plastid and one nuclear region sequence data, yielded the basis for a taxonomic reappraisal of the series. In this respect, a new comprehensive integrative taxonomic arrangement for Biscutella ser. Biscutella is presented in which 10 taxa are accepted, namely seven species and three additional varieties. The name B. eriocarpa DC. is reinterpreted and suggested to include the highest morphological variation found in northern Morocco. Its treatment here accepts two varieties, one of which is described as new (B. eriocarpa var. riphaea A. Vicente, M. A.´ Alonso & M. B. Crespo). In addition, the circumscriptions of several species, such as B. boetica Boiss. & Reut., B. didyma L., B. lyrata L., and B. maritima Ten., are revisited. Nomenclatural types, synonymy, brief descriptions, cytogenetic data, conservation status, distribution maps, and identification keys are included for the accepted taxa, with seven lectotypes and one epitype being designated here.