Architecture As Urban Practice in Contested Spaces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cheers Along! Wine Is Not a New Story for Cyprus

route2 Vouni Panagias - Ampelitis cheers along! Wine is not a new story for Cyprus. Recent archaeological excavations which have been undertaken on the island have confi rmed the thinking that this small tranche of earth has been producing wine for almost 5000 years. The discoveries testify that Cyprus may well be the cradle of wine development in the entire Mediterranean basin, from Greece, to Italy and France. This historic panorama of continuous wine history that the island possesses is just one Come -tour, taste of the reasons that make a trip to the wine villages such a fascinating prospect. A second and enjoy! important reason is the wines of today -fi nding and getting to know our regional wineries, which are mostly small and enchanting. Remember, though, it is important always to make contact fi rst to arrange your visit. The third and best reason is the wine you will sample during your journeys along the “Wine Routes” of Cyprus. From the traditional indigenous varieties of Mavro (for red and rosé wines) and the white grape Xynisteri, plus the globally unique Koumandaria to well - known global varieties, such as Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon and Shiraz. Let’s take a wine walk. The wine is waiting for us! Vineyard at Lemona 3 route2 Vouni Panagias - Ampelitis Pafos, Mesogi, Tsada, Stroumpi, Polemi, Psathi, Kannaviou, Asprogia, Pano Panagia, Chrysorrogiatissa, Agia Moni, Statos - Agios Fotios, Koilineia, Galataria, Pentalia, Amargeti, Eledio, Agia Varvara or Statos - Agios Fotios, Choulou, Lemona, Kourdaka, Letymvou, Kallepeia Here in this wine region, legend meets reality, as you travel ages old terrain, to encounter the young oenologists making today’s stylish Cyprus wines in 21st century wineries. -

Living Quarters, Households, Institutions and Population Enumerated by District, Municipality/Community and Quarter (1.10.2011)

LIVING QUARTERS, HOUSEHOLDS, INSTITUTIONS AND POPULATION ENUMERATED BY DISTRICT, MUNICIPALITY/COMMUNITY AND QUARTER (1.10.2011) LIVING QUARTERS HOUSEHOLDS INSTITUTIONS DISTRICT, GEO/CAL Vacant/ Of TOTAL MUNICIPALITY/COMMUNITY Of usual CODE Total temporary NumberPopulationNumberPopulation POPULATION AND QUARTER residence residence (1) Total 433,212 299,275 133,937 303,242 836,566 211 3,841 840,407 1 Lefkosia District 144,556 117,280 27,276 119,203 324,952 94 2,028 326,980 1000 Lefkosia Municipality 28,298 22,071 6,227 22,833 54,452 11 562 55,014 100001 Agios Andreas 2,750 2,157 593 2,206 5,397 4 370 5,767 100002 Trypiotis 1,293 949 344 1,009 2,158 2,158 100003 Nempetchane 109 80 29 93 189 189 100004 Tampakchane 177 133 44 159 299 299 100005 Faneromeni 296 228 68 264 512 512 100006 Agios Savvas 308 272 36 303 581 581 100007 Omerie 93 81 12 106 206 206 100008 Agios Antonios 3,231 2,485 746 2,603 5,740 2 61 5,801 100009 Agios Ioannis 114 101 13 111 216 1 5 221 100010 Taktelkale 369 317 52 332 814 1 12 826 100011 Chrysaliniotissa 71 56 15 58 124 124 100012 Agios Kassianos 49 28 21 28 82 82 100013 Kaïmakli 5,058 4,210 848 4,250 11,475 2 89 11,564 100014 Panagia 6,211 4,818 1,393 4,883 12,398 12,398 100015 Agioi Konstantinos kai Eleni 1,939 1,331 608 1,350 3,209 3,209 100016 Agioi Omologitai 5,971 4,609 1,362 4,855 10,503 1 25 10,528 100017 Arap Achmet 28 18 10 18 50 50 100018 Geni Tzami 114 93 21 98 215 215 100019 Omorfita 117 105 12 107 284 284 1010 Agios Dometios Municipality 5,825 4,824 1,001 4,931 12,395 4 61 12,456 101001 Agios Pavlos 1,414 -

Authentic Cyprus - Depliant.Pdf

Thanks to its year-round sunshine, blue skies and warm waters, Cyprus enjoys an enviable reputation as one of the world’s top sun, sea and sand holiday destinations. But this delightful island has much more to offer. Away from the tourist areas, the Cyprus countryside has a diverse wealth all of its own, including traditional villages, vineyards and wineries, tiny fresco-painted churches, remote monasteries and cool shady forests. This is a nature-lovers paradise, where you can walk for hours without seeing another living soul. In springtime, fields of flowers stretch as far as the eye can see, and a ramble along a mountain path will suddenly reveal a tiny Byzantine chapel or a Venetian-built bridge that once formed part of an ancient trade route. Around every corner is another surprise; a magnificent view; a rare sighting of the Cyprus moufflon; or a chance encounter with someone who will surprise you with their knowledge of your language and an invitation to join the family for a coffee. In the villages, traditional values remain, while the true character of the Cypriot people shines through wherever you go - warm-hearted, friendly, family-orientated, and unbelievably hospitable. Around 1200BC, the arrival of Greek-speaking settlers caused great disruption and led to the emergence of the first of the city kingdoms of the Iron Age. The influence of Greek culture rapidly Throughout the following centuries became evident in every of foreign domination, everyday life in the aspect of Cypriot life. more remote rural villages hardly changed Cultural until the beginning of the 20th century, During the Hellenistic period when electricity and motorised transport (4th century BC), copper mining was arrived and the first paved roads were generating such wealth that Cyprus constructed. -

The Latins of Cyprus

CYPRUS RELIGIOUS GROUPS O L T H a F E t C i n Y P s R U S Research/Text: Alexander-Michael Hadjilyra on behalf of the Latin religious group Editorial Coordination and Editing: Englightenment Publications Section, Press and Information Office Photos: Photographic archive of the Latin religious group Design: Anna Kyriacou Cover photo: Commemorative photo of Saint Joseph's School in Larnaka (early British era) The sale or other commercial exploitation of this publication or part of it is strictly prohibited. Excerpts from the publication may be reproduced with appropriate acknowledgment of this publication as the source of the material used. Press and Information Office publications are available free of charge. THE Latins OF CYP RUS Contents Foreword 5 A Message from the Representative of the Latin Religious Group 7 A Brief History 8 Frankish and Venetian Era 8 Ottoman Era 9 British Era 11 Independence Era 15 Demographic Profile 16 Important Personalities 17 The Latin Church of Cyprus 19 Churches and Chapels 20 Educational Institutions 22 Community Organisations and Activities 24 Monuments 25 The Heritage of the Frankish and the Venetian Eras 26 Cemeteries 29 Chronology 30 References 31 Foreword According to the Constitution of the Republic of Cyprus, the Armenians, the Latins and the Maronites of Cyprus are recognized as “religious groups”. In a 1960 referendum, the three religious groups were asked to choose to belong to either the Greek Cypriot or the Turkish Cypriot community. They opted to belong to the Greek Cypriot community. The members of all three groups, therefore, enjoy the same privileges, rights and benefits as the members of the Greek Cypriot community, including voting rights, eligibility for public office and election to official government and state positions, at all levels. -

Authentic Route 8

Cyprus Authentic Route 8 Safety Driving in Cyprus Only Comfort DIGITAL Rural Accommodation Version Tips Useful Information Off the Beaten Track Polis • Steni • Peristerona • Meladeia • Lysos • Stavros tis Psokas • Cedar Valley • Kykkos Monastery • Tsakistra • Kampos • Pano and Kato Pyrgos • Alevga • Pachyammos • Pomos • Nea Dimmata • Polis Route 8 Polis – Steni – Peristerona – Meladeia – Lysos – Stavros tis Psokas – Cedar Valley – Kykkos Monastery – Tsakistra – Kampos – Pano and Kato Pyrgos – Alevga – Pachyammos – Pomos – Nea Dimmata – Polis scale 1:300,000 Mansoura 0 1 2 4 6 8 Kilometers Agios Kato Kokkina Mosfili Theodoros Pyrgos Ammadies Pachyammos Pigenia Pomos Xerovounos Alevga Selladi Pano Agios Nea tou Appi Pyrgos Loutros Dimmata Ioannis Selemani Variseia Agia TILLIRIA Marina Livadi CHRYSOCHOU BAY Gialia Frodisia Argaka Makounta Marion Argaka Kampos Polis Kynousa Neo Chorio Pelathousa Stavros Tsakistra A tis Chrysochou Agios Isidoros Ε4 Psokas K Androlikou Karamoullides A Steni Lysos Goudi Cedar Peristerona Melandra Kykkos M Meladeia Valley Fasli Choli Skoulli Zacharia A Kios Tera Trimithousa Filousa Drouseia Kato Evretou S Mylikouri Ineia Akourdaleia Evretou Loukrounou Sarama Kritou Anadiou Tera Pano Akourdaleia Kato Simou Pano Miliou Kritou Arodes Fyti s Gorge Drymou Pano aka Arodes Lasa Marottou Asprogia Av Giolou Panagia Thrinia Milia Kannaviou Kathikas Pafou Theletra Mamountali Agios Dimitrianos Lapithiou Agia Vretsia Psathi Statos Moni Pegeia - Agios Akoursos Polemi Arminou Pegeia Fotios Koilineia Agios Stroumpi Dam Fountains -

Maritime Narratives of Prehistoric Cyprus: Seafaring As Everyday Practice

Journal of Maritime Archaeology (2020) 15:415–450 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11457-020-09277-7(0123456789().,-volV)(0123456789().,-volV) ORIGINAL PAPER Maritime Narratives of Prehistoric Cyprus: Seafaring as Everyday Practice A. Bernard Knapp1 Accepted: 8 September 2020 / Published online: 16 October 2020 Ó The Author(s) 2020 Abstract This paper considers the role of seafaring as an important aspect of everyday life in the communities of prehistoric Cyprus. The maritime capabilities developed by early seafarers enabled them to explore new lands and seas, tap new marine resources and make use of accessible coastal sites. Over the long term, the core activities of seafaring revolved around the exploitation of marine and coastal resources, the mobility of people and the transport and exchange of goods. On Cyprus, although we lack direct material evidence (e.g. shipwrecks, ship representations) before about 2000 BC, there is no question that begin- ning at least by the eleventh millennium Cal BC (Late Epipalaeolithic), early seafarers sailed between the nearby mainland and Cyprus, in all likelihood several times per year. In the long stretch of time—some 4000 years—between the Late Aceramic Neolithic and the onset of the Late Chalcolithic (ca. 6800–2700 Cal BC), most archaeologists passively accept the notion that the inhabitants of Cyprus turned their backs to the sea. In contrast, this study entertains the likelihood that Cyprus was never truly isolated from the sea, and considers maritime-related materials and practices during each era from the eleventh to the early second millennium Cal BC. In concluding, I present a broader picture of everything from rural anchorages to those invisible maritime behaviours that may help us better to understand seafaring as an everyday practice on Cyprus. -

Mfi Id Name Address Postal City Head Office

MFI ID NAME ADDRESS POSTAL CITY HEAD OFFICE CYPRUS Central Banks CY000001 Central Bank of Cyprus 80, Tzon Kennenty Avenue 1076 Nicosia Total number of Central Banks : 1 Credit Institutions CY130001 Allied Bank SAL 276, Archiepiskopou Makariou III Avenue 3105 Limassol LB Allied Bank SAL CY110001 Alpha Bank Limited 1, Prodromou Street 1095 Nicosia CY130002 Arab Bank plc 1, Santaroza Avenue 1075 Nicosia JO Arab Bank plc CY120001 Arab Bank plc 1, Santaroza Avenue 1075 Nicosia JO Arab Bank plc CY130003 Arab Jordan Investment Bank SA 23, Olympion Street 3035 Limassol JO Arab Jordan Investment Bank SA CY130006 Bank of Beirut and the Arab Countries SAL 135, Archiepiskopou Makariou III Avenue 3021 Limassol LB Bank of Beirut and the Arab Countries SAL CY130032 Bank of Beirut SAL 6, Griva Digeni Street 3106 Limassol LB Bank of Beirut SAL CY110002 Bank of Cyprus Ltd 51, Stasinou Street, Strovolos 2002 Nicosia CY130007 Banque Européenne pour le Moyen - Orient SAL 227, Archiepiskopou Makariou III Avenue 3105 Limassol LB Banque Européenne pour le Moyen - Orient SAL CY130009 Banque SBA 8C, Tzon Kennenty Street 3106 Limassol FR Banque SBA CY130010 Barclays Bank plc 88, Digeni Akrita Avenue 1061 Nicosia GB Barclays Bank plc CY130011 BLOM Bank SAL 26, Vyronos Street 3105 Limassol LB BLOM Bank SAL CY130033 BNP Paribas Cyprus Ltd 319, 28 Oktovriou Street 3105 Limassol CY130012 Byblos Bank SAL 1, Archiepiskopou Kyprianou Street 3036 Limassol LB Byblos Bank SAL CY151414 Co-operative Building Society of Civil Servants Ltd 34, Dimostheni Severi Street 1080 Nicosia -

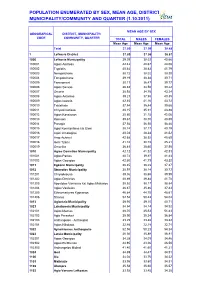

Population Enumerated by District

POPULATION ENUMERATED BY SEX, MEAN AGE, DISTRICT, MUNICIPALITY/COMMUNITY AND QUARTER (1.10.2011) MEAN AGE BY SEX GEOGRAFICAL DISTRICT, MUNICIPALITY/ CODE COMMUNITY, QUARTER TOTAL MALES FEMALES Mean Age Mean Age Mean Age Total 37.80 37.09 38.48 1 Lefkosia District 37.89 37.05 38.67 1000 Lefkosia Municipality 39.39 38.02 40.66 100001 Agios Andreas 42.42 40.67 44.08 100002 Trypiotis 40.44 38.83 41.79 100003 Nempetchane 38.72 38.02 39.30 100004 Tampakchane 39.19 38.38 39.71 100005 Faneromeni 38.11 36.47 39.77 100006 Agios Savvas 36.63 34.50 39.22 100007 Omerie 38.92 34.76 43.24 100008 Agios Antonios 39.21 37.98 40.35 100009 Agios Ioannis 42.45 41.16 43.72 100010 Taktelkale 37.54 35.44 39.66 100011 Chrysaliniotissa 40.15 35.91 43.88 100012 Agios Kassianos 35.80 31.15 42.06 100013 Kaimakli 39.67 38.70 40.59 100014 Panagia 37.54 36.55 38.48 100015 Agioi Konstantinos kai Eleni 38.74 37.17 40.19 100016 Agioi Omologitai 40.03 38.34 41.52 100017 Arap Achmet 42.68 38.52 45.69 100018 Geni Tzami 41.74 38.78 45.21 100019 Omorfita 36.81 35.60 37.95 1010 Agios Dometios Municipality 42.12 41.32 42.83 101001 Agios Pavlos 40.74 39.97 41.43 101002 Agios Georgios 42.60 41.79 43.32 1011 Egkomi Municipality 36.85 36.28 37.37 1012 Strovolos Municipality 38.97 38.14 39.72 101201 Chryseleousa 39.36 38.65 39.99 101202 Agios Dimitrios 40.89 39.88 41.78 101203 Apostolos Varnavas kai Agios Makarios 38.52 38.17 38.84 101204 Agios Vasileios 36.67 35.86 37.43 101205 Ethnomartyras Kyprianos 46.84 44.70 48.61 101206 Stavros 52.54 50.44 54.04 1013 Aglantzia Municipality 39.95 -

Spatial Analysis of Chipped Stone at the Cypro-PPNB Site of Krittou Marottou Ais Giorkis: a GIS-Assisted Study

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 12-1-2014 Spatial Analysis of Chipped Stone at the Cypro-PPNB Site of Krittou Marottou Ais Giorkis: A GIS-Assisted Study Levi Lowell Keach University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, and the Geographic Information Sciences Commons Repository Citation Keach, Levi Lowell, "Spatial Analysis of Chipped Stone at the Cypro-PPNB Site of Krittou Marottou Ais Giorkis: A GIS-Assisted Study" (2014). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2275. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/7048594 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPATIAL ANALYSIS OF CHIPPED STONE AT THE CYPRO-PPNB SITE OF KRITTOU MAROTTOU AIS GIORKIS: A GIS-ASSISTED STUDY By Levi Lowell Keach Bachelor of Arts in Anthropology University of Kansas 2012 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts -- Anthropology Department of Anthropology College of Liberal Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas December 2014 Licensed under Creative Commons by Levi Keach, 2014 Some Rights Reserved This thesis is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. -

Cyprus Authentic Route 6

Cyprus Authentic Route 6 Safety Driving in Cyprus Comfort Rural Accommodation Tips Useful Information Only DIGITAL Version The Magical West Pafos • Mesogi • Agios Neophytos monastery • Tsada • Kallepeia • Letymvou • Kourdaka • Lemona • Choulou • Statos • Agios Photios • Panagia Chrysorrogiatissa Monastery • Agia Moni Monastery • Pentalia • Agia Marina • Axylou • Nata • Choletria • Stavrokonnou • Kelokedara • Salamiou • Agios Ioannis • Arminou • Filousa • Praitori • Kedares • Kidasi • Agios Georgios • Mamonia • Fasoula • Souskiou • Kouklia • Palaipaphos • Pafos Route 6 Pafos – Mesogi – Agios Neophytos monastery – Tsada – Kallepeia – Letymvou – Kourdaka – Lemona – Choulou – Statos – Agios Photios – Panagia Chrysorrogiatissa Monastery – Agia Moni Monastery – Pentalia – Agia Marina – Axylou – Nata – Choletria – Stavrokonnou – Kelokedara – Salamiou – Agios Ioannis – Arminou – Filousa – Praitori – Kedares – Kidasi – Agios Georgios – Mamonia – Fasoula – Souskiou – Kouklia – Palaipaphos – Pafos Kato Akourdaleia Kato Pano Anadiou Arodes Akourdaleia Simou Kritou Kannaviou Dam Miliou Fyti as Gorge Pano Lasa Marottou Pano vak Asprogia A Arodes Giolou Drymou Panagia Milia Kannaviou Kathikas Thrinia Pafou Theletra Chrysorrogiatissa Mamountali Agios Agia Pegeia Psathi Lapithiou Dimitrianos Moni Vretsia Fountains Akoursos Stroumpi Statos - Pegeia Polemi Koilineia Arminou Agios Agios Choulou Dam Agios Fotios Galataria Ioannis Lemona Arminou Nikolaos Mavrokolympos Agios Koili Maa Letymvou Pentalia Neofytos Monastery Faleia Kourdaka Mesana Filousa Potima -

215 No. 226. the ELECTIONS (HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES and COMMUNAL CHAMBERS) LAWS, 1959 and 1960

215 No. 226. THE ELECTIONS (HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES AND COMMUNAL CHAMBERS) LAWS, 1959 AND 1960. ORDER MADE UNDER SECTION 19(1). In exercise of the powers vested in him by section 19 (1) of the Elections (House of Representatives and Communal Chambers) Laws, 1959 and 1960, His Excellency the Governor has been pleased to make the following Order :— 1. This Order may be cited as the Elections (House of Representatives and Communal Chambers) (Turkish Polling Districts) Order, 1960. 2. For the purpose of holding a poll for the election of Turkish members of the House of Representatives, and for the election of members of the Turkish Communal Chambers, the six Turkish constituencies in Cyprus shall be divided into the polling districts set out in the first column of the Schedule hereto, the names of the towns or villages the area of which comprise such polling district being shown in the second column of the said Schedule opposite thereto. SCHEDULE. The Turkish Constituency of Nicosia. Town or Villages included Polling District in Polling District Nicosia Town Nicosia Town Kutchuk Kaimakli (a) Kutchuk Kaimakli (b) Kaimakli (c) Η amid Mandres (d) Eylenja (e) Palouriotissa Geunycli (a) Geunyeli (b) Kanlikeuy Ortakeuy (a) Ortakeuy (b) Trachonas (c) Ay. Dhometios (d) Engomi Peristerona (a) Peristerona (b) Akaki (c) Dhenia (d) Eliophotes (e) Orounda Skylloura (a) Skylloura (b) Ay. Vassilios (c) Ay. Marina (Skyllouras) '(d) Dhyo Potami Epicho (a) Epicho (b) Bey Keuy (c) Neochorio (d) Palekythro (e) Kythrea Yenidje Keuy (a) Yenidje Keuy (b) Kourou Monastir (c) Kallivakia Kotchati (a) Kotchati (b) Nissou (c) Margi (d) Analiondas (e) Kataliondas Mathiatis Mathiatis Potamia (a) Potamia (b) Dhali (c) Ay. -

Bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) of the Eastern Mediterranean. Part 5. Bat

Acta Soc. Zool. Bohem. 71: 71–130, 2007 ISSN 1211-376X Bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) of the Eastern Mediterranean. Part 5. Bat fauna of Cyprus: review of records with confirmation of six species new for the island and description of a new subspecies Petr BENDA1,2,5), Vladimír HANÁK2), Ivan HORÁČEK2), Pavel HULVA2), Radek LUČAN3) & Manuel RUEDI4) 1) Department of Zoology, National Museum (Natural History), Václavské nám. 68, CZ–115 79 Praha 1, Czech Republic 2) Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, Charles University in Prague, Viničná 7, CZ–128 44 Praha 2, Czech Republic 3) Department of Zoology, University of South Bohemia, Branišovská 31, CZ–370 05 České Budějovice, Czech Republic 4) Department of Mammalogy and Ornithology, Natural History Museum of Geneva, C.P. 6434, CH–1211 Genève 6, Switzerland 5) corresponding author: [email protected] Received September 26, 2007; accepted October 8, 2007 Published October 30, 2007 Abstract. A complete list of bat records available from Cyprus, based on both the literature data and new records gathered during recent field studies. The review of records is added with distribution maps and summaries of the distribution statuses of particular species. From the island of Cyprus, at least 195 confirmed records of 22 bat species are known; viz. Rousettus aegyptiacus (Geoffroy, 1810) (50 record localities), Rhinolophus ferrumequinum (Schreber, 1774) (12), R. hipposideros (Borkhausen, 1797) (18), R. euryale Blasius, 1853 (1–2), R. mehelyi Matschie, 1901 (1), R. blasii Peters, 1866 (11), Myotis blythii (Tomes, 1857) (4), M. nattereri (Kuhl, 1817) (11), M. emarginatus (Geoffroy, 1806) (2), M. capaccinii (Bonaparte, 1837) (1), Eptesicus serotinus (Schreber, 1774) (6), E.