Resource Stress and Subsistence Practice in Early Prehistoric Cyprus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CYPRUS Cyprus in Your Heart

CYPRUS Cyprus in your Heart Life is the Journey That You Make It It is often said that life is not only what you are given, but what you make of it. In the beautiful Mediterranean island of Cyprus, its warm inhabitants have truly taken the motto to heart. Whether it’s an elderly man who basks under the shade of a leafy lemon tree passionately playing a game of backgammon with his best friend in the village square, or a mother who busies herself making a range of homemade delicacies for the entire family to enjoy, passion and lust for life are experienced at every turn. And when glimpsing around a hidden corner, you can always expect the unexpected. Colourful orange groves surround stunning ancient ruins, rugged cliffs embrace idyllic calm turquoise waters, and shady pine covered mountains are brought to life with clusters of stone built villages begging to be explored. Amidst the wide diversity of cultural and natural heritage is a burgeoning cosmopolitan life boasting towns where glamorous restaurants sit side by side trendy boutiques, as winding old streets dotted with quaint taverns give way to contemporary galleries or artistic cafes. Sit down to take in all the splendour and you’ll be made to feel right at home as the locals warmly entice you to join their world where every visitor is made to feel like one of their own. 2 Beachside Splendour Meets Countryside Bliss Lovers of the Mediterranean often flock to the island of Aphrodite to catch their breath in a place where time stands still amidst the beauty of nature. -

Cyprus Tourism Organisation Offices 108 - 112

CYPRUS 10000 years of history and civilisation CONTENTS CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5 CYPRUS 10000 years of history and civilisation 6 THE HISTORY OF CYPRUS 8200 - 1050 BC Prehistoric Age 7 1050 - 480 BC Historic Times: Geometric and Archaic Periods 8 480 BC - 330 AD Classical, Hellenistic and Roman Periods 9 330 - 1191 AD Byzantine Period 10 - 11 1192 - 1489 AD Frankish Period 12 1489 - 1571 AD The Venetians in Cyprus 13 1571 - 1878 AD Cyprus becomes part of the Ottoman Empire 14 1878 - 1960 AD British rule 15 1960 - today The Cyprus Republic, the Turkish invasion, 16 European Union entry LEFKOSIA (NICOSIA) 17 - 36 LEMESOS (LIMASSOL) 37 - 54 LARNAKA 55 - 68 PAFOS 69 - 84 AMMOCHOSTOS (FAMAGUSTA) 85 - 90 TROODOS 91 - 103 ROUTES Byzantine route, Aphrodite Cultural Route 104 - 105 MAP OF CYPRUS 106 - 107 CYPRUS TOURISM ORGANISATION OFFICES 108 - 112 3 LEFKOSIA - NICOSIA LEMESOS - LIMASSOL LARNAKA PAFOS AMMOCHOSTOS - FAMAGUSTA TROODOS 4 INTRODUCTION Cyprus is a small country with a long history and a rich culture. It is not surprising that UNESCO included the Pafos antiquities, Choirokoitia and ten of the Byzantine period churches of Troodos in its list of World Heritage Sites. The aim of this publication is to help visitors discover the cultural heritage of Cyprus. The qualified personnel at any Information Office of the Cyprus Tourism Organisation (CTO) is happy to help organise your visit in the best possible way. Parallel to answering questions and enquiries, the Cyprus Tourism Organisation provides, free of charge, a wide range of publications, maps and other information material. Additional information is available at the CTO website: www.visitcyprus.com It is an unfortunate reality that a large part of the island’s cultural heritage has since July 1974 been under Turkish occupation. -

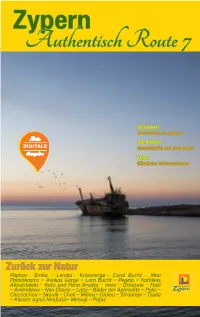

Zypern Authentisch Route 7

Zypern Authentisch Route 7 Sicherheit Autofahren in Zypern Nur Gemütliche DIGITALE Unterkünfte auf dem Land Ausgabe Tipps Nützliche Informationen Zurück zur Natur Paphos – Emba – Lemba – Kissonerga – Coral Bucht – Maa Palaiokastro – Avakas Gorge – Lara Bucht – Pegeia – Kathikas Akourdaleia – Kato und Pano Arodes – Ineia – Drouseia – Fasli – Androlikou – Neo Chorio – Latsi – Bäder der Aphrodite – Polis – Chrysochou – Skoulli – Choli – Miliou – Giolou – Stroumpi – Tsada – Kloster Agios Neofytos– Mesogi – Pafos Route 7 Paphos – Emba – Lemba – Kissonerga – Coral Bucht – Maa Palaiokastro – Avakas Gorge – Lara Bucht – Pegeia – Kathikas Akourdaleia – Kato und Pano Arodes – Ineia – Drouseia – Fasli – Androlikou – Neo Chorio – Latsi – Bäder der Aphrodite – Polis – Chrysochou – Skoulli – Choli – Miliou – Giolou – Stroumpi – Tsada – Kloster Agios Neofytos– Mesogi – Pafos Agia Marina Mazaki Islet T I L L I R I A Cape Arnaoutis Livadi (Akamas) CHRYSOCHOU BAY Gialia Ε4 Agios Georgios Islet Argaka Ryrgos tis Rigenas (Ruins) Makounta Loutra tis Marion Aphroditis (Baths Argaka of Aphrodite) Polis Kynousa Kioni Islet Neo Pelathousa Agios Chorio Stavros A Minas Agios tis Chrysochou K Isidoros Psokas Androlikou Karamoullides Lysos A Steni Goudi Peristerona M Melandra Fasli Meladeia Choli Skoulli Zacharia Agia AikaterinTirimithousa A Kios Drouseia Tera Church Filousa Kritou (15th cent) S Ineia Tera Kato Evretou Lara Sarama Akourdaleia Loukrounou Anadiou Simou Kato Arodes Pano Miliou Kannaviou Fyti Dam Gorge Pano Akourdaleia akas Drymou Lasa Kritou Av Arodes -

AMY PAPALEXANDROU Last Updated: 8/21/2019

AMY PAPALEXANDROU last updated: 8/21/2019 http://stockton.academia.edu/AmyPapalexandrou CURRICULUM VITAE EDUCATION PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Ph.D., Dept. of Art & Archaeology (January 24, 1998) Dissertation: ‘The Church of the Virgin of Skripou: Architecture, Sculpture and Inscriptions in Ninth-Century Byzantium’ (Advisor: Slobodan Ćurčić) M.A. in Art & Archaeology (January 19, 1991) UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS, Urbana-Champaign: Master of Architecture (May 1987) Bachelor of Science in Architecture (May 1985) TEACHING & PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE STOCKTON UNIVERSITY (Fall 2014 – Spring 2018) Constantine George Georges and Sophia G. Georges Associate Professor of Greek Art & Architecture (Associate Professor of Art History) School of Arts and Humanities – Program in the Visual Arts Courses taught: ARTV 3337 Ancient Greek Art & Architecture, Spring 2014 ARTV 3338 /ANTH 3338 Archaeology of the Mediterranean World Spring 2014, 2015, Fall 2015, 2016, Spring 2017, 2018 ARTV 20548 /GAH 2118 Jews, Christians, Muslims (The Three Abrahamic Faiths on Pilgrimage) Spring 2014, 2018 ARTV 2175 Intro to the History of Art I, Prehistoric to Gothic, Fall 2014, 2017, Spring 2015, 2017 ARTV 2176 Intro to the History of Art II, Ren. to 20thCentury, Fall 2015, 2016, 2017, Spring 2018 ARTV 3340 Byzantine Art & Architecture, Fall 2014 ARTV 3340 Medieval Art, Fall 2017 ARTV 3339 Art in the Shadow of Rome, Fall 2015, Spring 2017 ARTV 2177 Introduction to the History of Architecture, Spring 2016 ARTV 4950 Senior Project I, Fall 2017 ARTV 4950 Senior Project II, Spring 2018 -

This Pdf of Your Paper in Cyprus: an Island Culture Belongs to the Publishers Oxbow Books and It Is Their Copyright

This pdf of your paper in Cyprus: An Island Culture belongs to the publishers Oxbow Books and it is their copyright. As author you are licenced to make up to 50 offprints from it, but beyond that you may not publish it on the World Wide Web until three years from publication (September 2015), unless the site is a limited access intranet (password protected). If you have queries about this please contact the editorial department at Oxbow Books ([email protected]). An offprint from CYPRUS An Island Culture Society and Social Relations from the Bronze Age to the Venetian Period edited by Artemis Georgiou © Oxbow Books 2012 ISBN 978-1-84217-440-1 www.oxbowbooks.com CONTENTS Preface Acknowledgements Abbreviations 1. TEXT MEETS MATERIAL IN LATE BRONZE AGE CYPRUS.......................................... 1 (Edgar Peltenburg) Settlements, Burials and Society in Ancient Cyprus 2. EXPANDING AND CHALLENGING HORIZONS IN THE CHALCOLITHIC: NEW RESULTS FROM SOUSKIOU-LAONA .................................................................... 24 (David A. Sewell) 3. THE NECROPOLIS AT KISSONERGA-AMMOUDHIA: NEW CERAMIC EVIDENCE FROM THE EARLY-MIDDLE BRONZE AGE IN WESTERN CYPRUS.......................... 38 (Lisa Graham) 4. DETECTING A SEQUENCE: STRATIGRAPHY AND CHRONOLOGY OF THE WORKSHOP COMPLEX AREA AT ERIMI-LAONIN TOU PORAKOU............................ 48 (Luca Bombardieri) 5. PYLA-KOKKINOKREMOS AND MAA-PALAEOKASTRO: A COMPARISON OF TWO NATURALLY FORTIFIED LATE CYPRIOT SETTLEMENTS ....................................... 65 (Artemis Georgiou) 6. -

Authentic Route 8

Cyprus Authentic Route 8 Safety Driving in Cyprus Only Comfort DIGITAL Rural Accommodation Version Tips Useful Information Off the Beaten Track Polis • Steni • Peristerona • Meladeia • Lysos • Stavros tis Psokas • Cedar Valley • Kykkos Monastery • Tsakistra • Kampos • Pano and Kato Pyrgos • Alevga • Pachyammos • Pomos • Nea Dimmata • Polis Route 8 Polis – Steni – Peristerona – Meladeia – Lysos – Stavros tis Psokas – Cedar Valley – Kykkos Monastery – Tsakistra – Kampos – Pano and Kato Pyrgos – Alevga – Pachyammos – Pomos – Nea Dimmata – Polis scale 1:300,000 Mansoura 0 1 2 4 6 8 Kilometers Agios Kato Kokkina Mosfili Theodoros Pyrgos Ammadies Pachyammos Pigenia Pomos Xerovounos Alevga Selladi Pano Agios Nea tou Appi Pyrgos Loutros Dimmata Ioannis Selemani Variseia Agia TILLIRIA Marina Livadi CHRYSOCHOU BAY Gialia Frodisia Argaka Makounta Marion Argaka Kampos Polis Kynousa Neo Chorio Pelathousa Stavros Tsakistra A tis Chrysochou Agios Isidoros Ε4 Psokas K Androlikou Karamoullides A Steni Lysos Goudi Cedar Peristerona Melandra Kykkos M Meladeia Valley Fasli Choli Skoulli Zacharia A Kios Tera Trimithousa Filousa Drouseia Kato Evretou S Mylikouri Ineia Akourdaleia Evretou Loukrounou Sarama Kritou Anadiou Tera Pano Akourdaleia Kato Simou Pano Miliou Kritou Arodes Fyti s Gorge Drymou Pano aka Arodes Lasa Marottou Asprogia Av Giolou Panagia Thrinia Milia Kannaviou Kathikas Pafou Theletra Mamountali Agios Dimitrianos Lapithiou Agia Vretsia Psathi Statos Moni Pegeia - Agios Akoursos Polemi Arminou Pegeia Fotios Koilineia Agios Stroumpi Dam Fountains -

A4 ENGLISH-Text

CYPRUS TOURISM ORGANISATION yprus may be a small country, but C it’s a large island - the third largest in the Mediterranean. And it’s an island with a big heart - an island that gives its visitors a genuine welcome and treats them as friends. With its spectacular scenery and enviable climate, it’s no wonder that Aphrodite chose the island as her playground, and since then, mere mortals have been discovering this ‘land fit for Gods’ for themselves. Cyprus is an island of beauty and a country of contrasts. Cool, pine-clad mountains are a complete scene-change after golden sun- kissed beaches; tranquil, timeless villages are in striking contrast to modern cosmopolitan towns; luxurious beachside hotels can be exchanged for large areas of natural, unspoilt countryside; yet in Cyprus all distances are easily manageable, mostly on modern roads and highways - with a secondary route or two for the more adventurous. Most important of all, the island offers peace of mind. At a time when holidays Cyprus are clouded by safety consciousness, a feeling of security prevails everywhere since the crime level is so low as to be practically non-existent. 1 1 ew countries can trace the course of their history over 10.000 years, but F in approximately 8.000 B.C. the island of Cyprus was already inhabited and going through its Neolithic Age. Of all the momentous events that were to sweep the country through the next few 2 thousand years, one of the most crucial was the discovery of copper - or Kuprum in Latin - the mineral which took its name from “Kypros”, the Greek name of Cyprus, and generated untold wealth. -

The Hideaway 2 Bedroom House with Jacuzzi Hot Tub

The Hideaway 2 Bedroom House with Jacuzzi hot tub DHRYNIA, POLIS, PAPHOS, CYPRUS • Sleeps 2 – 4 + infant • Air conditioning • Rural, secluded & quiet • Heatable Jacuzzi on upstairs terrace, not overlooked • Gym, pool table, 2 sitting areas • 2 – 4 person low web rates Unique. Hot tub on 1st floor. Gym and pool table. Comfortable stone house, cosy in cooler months, cool in summer. Situated in a non-touristic sleepy hamlet. Wi-Fi, modern kitchen, air con. 2 – 4 person lower rates on web. No pool This lovely well insulated stone house, beautifully restored by its craftsman owner, is quietly located tucked away in a sleepy hamlet which is off the beaten track. The thick stone walls keep it cool in summer and warm in winter. The air conditioned master bedroom on the first floor has access to a large terrace which runs from the side to across the back of the house. Here you find a spacious sitting area equipped with cushioned rattan furniture and sun loungers. This is a lovely spot for you to soak up the quiet village atmosphere of this unique rental. Continuing round towards the back of the house you enter the 2nd part of the 1st floor terrace featuring your Jacuzzi behind privacy screening, and equipped with sun awning and umbrella in case you need shade. From here you can enjoy the far reaching rural views whilst in the Jacuzzi. The heated Jacuzzi hot tub is completely private, and is an optional extra to be pre-booked (with fresh heated water), so it is ready for you to use upon arrival. -

Mfi Id Name Address Postal City Head Office

MFI ID NAME ADDRESS POSTAL CITY HEAD OFFICE CYPRUS Central Banks CY000001 Central Bank of Cyprus 80, Tzon Kennenty Avenue 1076 Nicosia Total number of Central Banks : 1 Credit Institutions CY130001 Allied Bank SAL 276, Archiepiskopou Makariou III Avenue 3105 Limassol LB Allied Bank SAL CY110001 Alpha Bank Limited 1, Prodromou Street 1095 Nicosia CY130002 Arab Bank plc 1, Santaroza Avenue 1075 Nicosia JO Arab Bank plc CY120001 Arab Bank plc 1, Santaroza Avenue 1075 Nicosia JO Arab Bank plc CY130003 Arab Jordan Investment Bank SA 23, Olympion Street 3035 Limassol JO Arab Jordan Investment Bank SA CY130006 Bank of Beirut and the Arab Countries SAL 135, Archiepiskopou Makariou III Avenue 3021 Limassol LB Bank of Beirut and the Arab Countries SAL CY130032 Bank of Beirut SAL 6, Griva Digeni Street 3106 Limassol LB Bank of Beirut SAL CY110002 Bank of Cyprus Ltd 51, Stasinou Street, Strovolos 2002 Nicosia CY130007 Banque Européenne pour le Moyen - Orient SAL 227, Archiepiskopou Makariou III Avenue 3105 Limassol LB Banque Européenne pour le Moyen - Orient SAL CY130009 Banque SBA 8C, Tzon Kennenty Street 3106 Limassol FR Banque SBA CY130010 Barclays Bank plc 88, Digeni Akrita Avenue 1061 Nicosia GB Barclays Bank plc CY130011 BLOM Bank SAL 26, Vyronos Street 3105 Limassol LB BLOM Bank SAL CY130033 BNP Paribas Cyprus Ltd 319, 28 Oktovriou Street 3105 Limassol CY130012 Byblos Bank SAL 1, Archiepiskopou Kyprianou Street 3036 Limassol LB Byblos Bank SAL CY151414 Co-operative Building Society of Civil Servants Ltd 34, Dimostheni Severi Street 1080 Nicosia -

Lem Esos Bay Larnaka Bay Vfr Routes And

AIP CYPRUS LARNAKA APP : 121.2 MHz AD2 LCLK 24 VFR VFR ROUTES - ICAO LARNAKA TWR : 119.4 MHz AERONAUTICAL INFORMATION 09/05/2009 10' 20' 30' 40' 50' 33° E 33° E 33° E 33° E 33° E Nicosia Airport (645) (740) remains closed Tower REPUBLIC OF CYPRUS Mammari until further notice Crane 10' 10' (480) 35° N 35° N (465) LEFKOSIA VFR ROUTES AND TRAINING AREAS 02 BUFFER (760) (825) (850) CYTA Stadium CBC Tower ZONE (905) Tower BUFFER SCALE : 1:250000 Astromeritis Pylons (595) Tower (600) (570) ZONE AREA UNDER TURKISH OCCUPATION Positions are referred to World Geodetic System 1984 Datum . (625) Elevations and Altitudes are in feet above Mean Sea Level. Akaki Palaiometocho Bearings and Tracks are magnetic. (745) Distances are in Nautical miles. Peristerona (1065) GSP Stadium Magnetic Variation : 04°00’E (2008) Mast LC(R) Pylons Projection : UTM Zone 36 Northern Hemisphere. Potami (595) Geri Sources : The aeronautical data have been designed by the KLIROU Lakatamia VAR 4° E (925)Lakatameia Department of Civil Aviation. The chart has been compiled by the Agios Orounta 46 122.5 MHz LC(D)-18 3000ft Department of Lands and Surveys using sources available in the Nikolaos Kato Deftera max 5000 ft 3500ft 1130 SFC Geographic Database. 1235 SFC LC(D)-37 1030 Vyzakia 1145 Tseri 7 19 10000ft 54 Agios 34 2 LC(D)-15 LC(D)-20 SFC Ioannis 1340 FL105 (1790) Vyzakia 1760 SFC Kato Moni Agios Psimolofou Mast LC(D)-06 dam Panteleimon Ergates SBA Boundary LEGEND 2110 3000ft 2025 (1140) Idalion SFC Achna Arediou MARKI Potamia AERONAUTICAL HYDROLOGICAL Klirou PERA dam FEATURES FEATURES dam 106° 122.5 MHz Mitsero N 35°01'57" 3000ft BUFFER 2225 MOSPHILOTI Kingsfield VFR route Aeronautical Water LC(D)-19 E 033°15'15" ZONE Xyliatos 7.6 NM 1195 N 34°57'12" reporting 6000ft Klirou Agios Xylotymvou ground reservoir 1605 Irakleidios 1465 points 3120 SFC KLIROU E 033°25'12" Pyla lights Tamassos Xyliatos Ag. -

Cyprus Authentic Route 6

Cyprus Authentic Route 6 Safety Driving in Cyprus Comfort Rural Accommodation Tips Useful Information Only DIGITAL Version The Magical West Pafos • Mesogi • Agios Neophytos monastery • Tsada • Kallepeia • Letymvou • Kourdaka • Lemona • Choulou • Statos • Agios Photios • Panagia Chrysorrogiatissa Monastery • Agia Moni Monastery • Pentalia • Agia Marina • Axylou • Nata • Choletria • Stavrokonnou • Kelokedara • Salamiou • Agios Ioannis • Arminou • Filousa • Praitori • Kedares • Kidasi • Agios Georgios • Mamonia • Fasoula • Souskiou • Kouklia • Palaipaphos • Pafos Route 6 Pafos – Mesogi – Agios Neophytos monastery – Tsada – Kallepeia – Letymvou – Kourdaka – Lemona – Choulou – Statos – Agios Photios – Panagia Chrysorrogiatissa Monastery – Agia Moni Monastery – Pentalia – Agia Marina – Axylou – Nata – Choletria – Stavrokonnou – Kelokedara – Salamiou – Agios Ioannis – Arminou – Filousa – Praitori – Kedares – Kidasi – Agios Georgios – Mamonia – Fasoula – Souskiou – Kouklia – Palaipaphos – Pafos Kato Akourdaleia Kato Pano Anadiou Arodes Akourdaleia Simou Kritou Kannaviou Dam Miliou Fyti as Gorge Pano Lasa Marottou Pano vak Asprogia A Arodes Giolou Drymou Panagia Milia Kannaviou Kathikas Thrinia Pafou Theletra Chrysorrogiatissa Mamountali Agios Agia Pegeia Psathi Lapithiou Dimitrianos Moni Vretsia Fountains Akoursos Stroumpi Statos - Pegeia Polemi Koilineia Arminou Agios Agios Choulou Dam Agios Fotios Galataria Ioannis Lemona Arminou Nikolaos Mavrokolympos Agios Koili Maa Letymvou Pentalia Neofytos Monastery Faleia Kourdaka Mesana Filousa Potima -

43. Pleistocene Fanglomerate Deposition Related to Uplift of the Troodos Ophiolite, Cyprus1

Robertson, A.H.F., Emeis, K.-C., Richter, C., and Camerlenghi, A. (Eds.), 1998 Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results, Vol. 160 43. PLEISTOCENE FANGLOMERATE DEPOSITION RELATED TO UPLIFT OF THE TROODOS OPHIOLITE, CYPRUS1 Andrew Poole2 and Alastair Robertson3 ABSTRACT The Pleistocene Fanglomerate Group of the southern part of Cyprus exemplifies coarse alluvial clastic deposition within a zone of focused tectonic uplift, related to collision of African and Eurasian plates, as documented by Ocean Drilling Program Leg 160. During the Pleistocene, the Troodos ophiolite was progressively unroofed, resulting in a near-radial pattern of coarse clastic sedimentation. The Pleistocene Fanglomerate Group depositionally overlies Pliocene marine sediments. Along the southern margin of the Troodos Massif the contact is erosional, whereas along its northern margin a regressive fan-delta (Kakkaristra Fm.) intervenes. The Pleistocene Fanglomerate Group is subdivided into four units (termed F1−F4), each of which were formed at progres- sively lower topographic levels. A wide variety of alluvial units are recognized within these, representing mainly high-energy coarse alluvial fans, channel fans, braidstream, and floodplain environments. A near-radial sediment dispersal pattern away from Mt. Olympos is indicated by paleocurrent studies, based on clast imbrication. Provenance studies indicate relatively early unroofing of the ophiolite, but with only minor localized erosion of ultramafic rocks from the Mt. Olympos area. Clasts of erosionally resistant lithologies, notably ophiolitic diabase and Miocene reef- related limestone, are volumetrically over-represented, relative to friable basalt and early Tertiary pelagic carbonate sediments. The younger Fanglomerate Group units (F3 and F4) can be correlated with littoral marine terraces previously dated radio- metrically at about 185−219 ka and 116−134 ka, respectively.