Sarasvati in the Veda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swami Vivekananda and Sri Aurobindo Ghosh

UNIT 6 HINDUISM : SWAMI VIVEKANANDA AND SRI AUROBINDO GHOSH Structure 6.2 Renaissance of Hi~~duis~iiand the Role of Sri Raniakrishna Mission 0.3 Swami ViveItananda's Philosopliy of Neo-Vedanta 6.4 Swami Vivckanalida on Nationalism 6.4.1 S\varni Vivcknnnnda on Dcrnocracy 6.4.2 Swami Vivckanar~daon Social Changc 6.5 Transition of Hinduism: Frolii Vivekananda to Sri Aurobindo 6.5. Sri Aurobindo on Renaissance of Hinduism 6.2 Sri Aurol>i~ldoon Evil EffLrcls of British Rulc 6.6 S1.i Aurobindo's Critique of Political Moderates in India 6.6.1 Sri Aurobilido on the Essencc of Politics 6.6.2 SI-iAurobindo oil Nationalism 0.6.3 Sri Aurobindo on Passivc Resistance 6.6.4 Thcory of Passive Resistance 6.6.5 Mcthods of Passive Rcsistancc 6.7 Sri Aurobindo 011 the Indian Theory of State 6.7.1 .J'olitical ldcas of Sri Aurobindo - A Critical Study 6.8 Summary 1 h 'i 6.9 Exercises j i 6.1 INTRODUCTION In 19"' celitury, India camc under the British rule. Due to the spread of moder~ieducation and growing public activities, there developed social awakening in India. The religion of Hindus wns very harshly criticized by the Christian n?issionaries and the British historians but at ~hcsanie timc, researches carried out by the Orientalist scholars revealcd to the world, lhc glorioi~s'tiaadition of the Hindu religion. The Hindus responded to this by initiating reforms in thcir religion and by esfablishing new pub'lie associations to spread their ideas of refor111 and social development anlong the people. -

Companion to Hymns to the Mystic Fire

Companion to Hymns to the Mystic Fire Volume III Word by word construing in Sanskrit and English of Selected ‘Hymns of the Atris’ from the Rig-veda Compiled By Mukund Ainapure i Companion to Hymns to the Mystic Fire Volume III Word by word construing in Sanskrit and English of Selected ‘Hymns of the Atris’ from the Rig-veda Compiled by Mukund Ainapure • Original Sanskrit Verses from the Rig Veda cited in The Complete Works of Sri Aurobindo Volume 16, Hymns to the Mystic Fire – Part II – Mandala 5 • Padpātha Sanskrit Verses after resolving euphonic combinations (sandhi) and the compound words (samās) into separate words • Sri Aurobindo’s English Translation matched word-by-word with Padpātha, with Explanatory Notes and Synopsis ii Companion to Hymns to the Mystic Fire – Volume III By Mukund Ainapure © Author All original copyrights acknowledged April 2020 Price: Complimentary for personal use / study Not for commercial distribution iii ॥ी अरिव)दचरणारिव)दौ॥ At the Lotus Feet of Sri Aurobindo iv Prologue Sri Aurobindo Sri Aurobindo was born in Calcutta on 15 August 1872. At the age of seven he was taken to England for education. There he studied at St. Paul's School, London, and at King's College, Cambridge. Returning to India in 1893, he worked for the next thirteen years in the Princely State of Baroda in the service of the Maharaja and as a professor in Baroda College. In 1906, soon after the Partition of Bengal, Sri Aurobindo quit his post in Baroda and went to Calcutta, where he soon became one of the leaders of the Nationalist movement. -

(Rjelal) Magic Consciousness and Life Negation of Sri

Research Journal of English Language and Literature (RJELAL) A Peer Reviewed (Refereed) International Vol.3.3.2015 (July-Sep) Journalhttp://www.rjelal.com RESEARCH ARTICLE MAGIC CONSCIOUSNESS AND LIFE NEGATION OF SRI AUROBINDO’S SELECT POEMS S.KARTHICK1, Dr. O.T. POONGODI2 1(Ph.D) Research Scholar, R & D Cell, Bharathiar Universty, Coimbatore. 2Assistant Professor of English, Thiruvalluvar Govt. Arts College Rasipuram. ABSTRACT Magic consciousness and Life Negation are the divine inclination principle of human being. Spiritual practice made to uplift their eternal journey. It had nothing to do with materialistic worshippers. The dawn of the higher or undivided magic consciousness is only for the super-men who had the right to enter into communion soul with the supra- sensuous. The aim of this paper is to through the light on sacred essence of Sri Aurobindo’s select poems. Under this influences one of the popular imaginations of Atman for the immaterial part of the individual. S.KARTHICK Aurobindo’s poetry asserts that the illuminating hidden meaning of the Vedas. It brings untrammeled inner reflection of the Upanishads. The world of life negation comes from supra- sensuous. It is a truism that often a long writing of the Vedas has come to practice. The Vedas, Upanishads were only handed down orally. In this context seer poets like Sri Aurobindo has intertwined the secret instruction about the hidden meaning of Magic consciousness and Life negation through his poetry. Key words: Supra- Sensuous, Mythopoeic Visionary and Atman. ©KY PUBLICATIONS INTRODUCTION inner truth of Magic consciousness and Life negation “The force varies always according to the cannot always be separated from the three co- power of consciousness which it related aspects of Mystical, Philosophy and Ecstatic. -

Institute of Human Study Hyderabad

A Journal of Integral and Future Studies Published by Institute of Human Study Hyderabad Volume IVi Issue II Volume IV Issue II NEW RACE is published by Chhalamayi Reddy on behalf of Institute of Human Study, 2-2-4/1, O.U.Road, Hyderabad 500 044. Founder Editor : (Late) Prof. V. Madhusudan Reddy Editor-in-Chief: V. Ananda Reddy Assistant Editor: Shruti Bidwaikar Designing: Vipul Kishore Email: [email protected]; Phone: 040 27098414 On the web: www.instituteofhumanstudy.org ISSN No.: 2454–1176 ii Volume IV Issue II NEW RACE A Journal of Integral & Future Studies August 2018 Volume IV Issue 2 CONTENTS From the Editor's Desk... Section II: Beauty and Delight 36 Shruti Bidwaikar iv Beauty in Women Sri Aurobindo 37 Section I: Truth 1 Laxmiben Patel’s Work Swami Vivekananda: with the Mother “A Soul of Puissance” Deepshikha Reddy 39 Sri Aurobindo 2 The First Flight... (a sketch) “I had some Strange Power” Deepshikha Reddy 42 Swami Vivekananda 4 Towards a Theory of Poetic Creation Sri Aurobindo: Vinod Balakrishnan 43 Bridge between the Section III: Life 47 Past and the Future The Finnish Education Model: M. P. Pandit 7 In the Light of the Mother’s Essays on Education Significance of Sridarshan Koundinya 48 Sri Aurobindo’s Relics Self-Determination and Ananda Reddy 15 the Path Ahead Evolution Next Kisholoy Gupta 53 Alok Pandey 26 Coming in the Clasp of Divine Grace Search for the Unity of Dolan 57 Matter and Energy Sketches of Life Narendra Joshi 31 Oeendrila Guha 59 iii Volume IV Issue II From the Editor's Desk.. -

“The Theory of Political Resistance - a Review & Dr

Vol. 4(6), pp. 187-192, July 2016 DOI: 10.14662/IJPSD2016.019 International Journal of Copy©right 2016 Political Science and Author(s) retain the copyright of this article ISSN: 2360-784X Development http://www.academicresearchjournals.org/IJPSD/Index.html Full Length Research “The Theory of Political Resistance - A Review & Dr. B.R. Ambedkar‟s Approach” Mr. Vishal Lahoo Kamble Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Dr. Ptangrao Kadam Arts & Commerce College, Pen. Dist- Raigad.( Maharashtra), India. E- Mail: [email protected] Accepted 12 June 2016 The Resistance, woes of an individual can be made general and by raising a collective struggle movement it can be redressed. It means resistance is an in born tool humans have obtained. The reaction of resistance is made clear by biology. The ancient times in India, such theory of resistance was laid down, for the first time, by Gautama Buddha. Dr. Babasaheb Amdedkar, who was generally influenced by the philosophical thought of Gautama Buddha raised a movement against the established, traditional social system which had inflicted in justices on so called untouchable, down- trodden castes, for the purpose of getting them the human right and human values. His movement was of social and political nature, through which, he accepted the waddle way expected by Gautama Buddha and thus, put forth his theory of social and political resistance. In the modern times western thinkers also have Henry Thoreau‟s expressed the concept of civil disobedience through the feeling of resistance. Tolstoy was another philosopher who professed philosophy of resistance through (insistence on truth) and non-co-operation. -

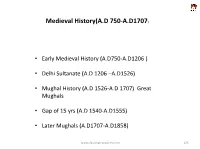

Medieval History(A.D 750-A.D1707)

Medieval History(A.D 750-A.D1707) • Early Medieval History (A.D750-A.D1206 ) • Delhi Sultanate (A.D 1206 –A.D1526) • Mughal History (A.D 1526-A.D 1707) Great Mughals • Gap of 15 yrs (A.D 1540-A.D1555) • Later Mughals (A.D1707-A.D1858) www.classmateacademy.com 125 The years AD 750-AD 1206 • Origin if Indian feudalism • Economic origin beginning with land grants first by satavahana • Political origin it begins in Gupta period ,Samudragupta started it (samantha system) • AD750-AD950 peak of feudalism ,it continues under sultanate but its nature changes they allowed fuedalism to coexist. www.classmateacademy.com 126 North India (A.D750 –A.D950) Period of Triangular Conflict –Pala,Prathihara,Rashtrakutas Gurjara Prathiharas-West Pala –Pataliputra • Naga Bhatta -1 ,defends wetern border • Started by Gopala • Mihira bhoja (Most powerful) • Dharmapala –most powerful,Patron of Buddhism • Capital -Kannauj Est.Vikramshila university Senas • Vijayasena founder • • Last ruler –Laxmana sena Rashtrakutas defeated by • Dantidurga-founder, • Bhakthiyar Khalji(A.D1206) defeated Badami Chalukyas (Dasavatara Cave) • Krishna-1 Vesara School of architecture • Amoghvarsha Rajputs and Kayasthas the new castes of Medival India New capital-Manyaketa Patron-Jainism &Kannada Famous works-Kavirajamarga,Ratnamalika • Krishna-3 last powerful ruler www.classmateacademy.com 127 www.classmateacademy.com 128 www.classmateacademy.com 129 www.classmateacademy.com 130 www.classmateacademy.com 131 Period of mutlicornered conflict-the 4 Agni Kulas(AD950-AD1206) Chauhans-Ajayameru(Ajmer) Solankis Pawars Ghadwala of Kannauj • Prithviraj chauhan-3 Patronn of Jainsim Bhoja Deva -23 classical Jayachandra (last) • PrthvirajRasok-ChandBardai Dilwara temples of Mt.Abu works in sanskrit • Battle of Tarain-1 Nagara school • Battle of tarain-2(1192) Chandellas of bundelKhand Tomars of Delhi Kajuraho AnangaPal _Dillika www.classmateacademy.com 132 Meanwhile in South India.. -

Books on and by Bal Gangadhar Tilak (Birth Anniversary on 23Rd July

Books on and by Bal Gangadhar Tilak (Birth Anniversary on 23rd July) (English Books) Sr. Title Author Publisher and Year of No. Address Publication 1. Vedic chronology and Bal Gangadhar Messers Tilak Bros., 1925 vedanga jyotisha Tilak Poona 2. Srimad Bhagavadgita Bal Gangadhar R.B. Tilak, 1935 rahasya or Karma-yoga- Tilak Lokamanya Tilak sastra. Mandir, Poona 3. Lokmanya Tilk: Father of D.V. Tahmankar John Murray, 1956 Indian unrest and maker London of modern India 4. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: a D.P. Karmarkar Popular Book 1956 study Depot, Bombay 5. Lokmanya Tilak: a Ram Gopal Asia Publishing 1956 Biography House, Bombay 6. Lok many Bal Gangadhar S.L. Karandikar, ---- 1957 Tilak; the Hercules and Prometheus of modern India 7. Lokamanya Tilak; a G.P. and Bhagwat, Jaico Publishing 1959 biography A.K. Pradhan House, Bombay 8. Lokamanya N.G. Jog Ministry of 1962 Balgangadhar Tilak Information and Broadcasting, New Delhi 9. Tilak and Gokhale: Stanley A. Wolpert University of 1962 revolution and reform in California Press , the making of modern Berkeley India 10. Letters of Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Kesari Prakashan, 1966 Tilak Tilak Poona 11. Tilak and the struggle for Reisner, I.M. and People’s publication 1966 Indian freedom Goldberg, N.M. House, New Delhi 12. Lokamanya Tilak: father Dhananjay Keer Popular Prakashan, 1969 of the Indian freedom Bombay struggle 13. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: a T.V. Parvate Navajivan 1972 narrative and Publishing House, interpretative review of Ahmedabad his life, career and contemporary events 14. The myth of the Richard I. Cashman University of 1975 Lokamanya California Press, California 15. -

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings & Speeches Vol. 4

Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar (14th April 1891 - 6th December 1956) BLANK DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR WRITINGS AND SPEECHES VOL. 4 Compiled by VASANT MOON Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar : Writings and Speeches Vol. 4 First Edition by Education Department, Govt. of Maharashtra : October 1987 Re-printed by Dr. Ambedkar Foundation : January, 2014 ISBN (Set) : 978-93-5109-064-9 Courtesy : Monogram used on the Cover page is taken from Babasaheb Dr. Ambedkar’s Letterhead. © Secretary Education Department Government of Maharashtra Price : One Set of 1 to 17 Volumes (20 Books) : Rs. 3000/- Publisher: Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Govt. of India 15, Janpath, New Delhi - 110 001 Phone : 011-23357625, 23320571, 23320589 Fax : 011-23320582 Website : www.ambedkarfoundation.nic.in The Education Department Government of Maharashtra, Bombay-400032 for Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Source Material Publication Committee Printer M/s. Tan Prints India Pvt. Ltd., N. H. 10, Village-Rohad, Distt. Jhajjar, Haryana Minister for Social Justice and Empowerment & Chairperson, Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Kumari Selja MESSAGE Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the Chief Architect of Indian Constitution was a scholar par excellence, a philosopher, a visionary, an emancipator and a true nationalist. He led a number of social movements to secure human rights to the oppressed and depressed sections of the society. He stands as a symbol of struggle for social justice. The Government of Maharashtra has done a highly commendable work of publication of volumes of unpublished works of Dr. Ambedkar, which have brought out his ideology and philosophy before the Nation and the world. In pursuance of the recommendations of the Centenary Celebrations Committee of Dr. -

Hymns to the Mystic Fire

16 Hymns to the Mystic Fire VOLUME 16 THE COMPLETE WORKS OF SRI AUROBINDO © Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust 2013 Published by Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department Printed at Sri Aurobindo Ashram Press, Pondicherry PRINTED IN INDIA Hymns To The Mystic Fire Publisher’s Note The present volume comprises Sri Aurobindo’s translations of and commentaries on hymns to Agni in the Rig Veda. It is divided into three parts: Hymns to the Mystic Fire: The entire contents of a book of this name that was published by Sri Aurobindo in 1946, consisting of selected hymns to Agni with a Fore- word and extracts from the essay “The Doctrine of the Mystics”. Other Hymns to Agni: Translations of hymns to Agni that Sri Aurobindo did not include in the edition of Hymns to the Mystic Fire published during his lifetime. An appendix to this part contains his complete transla- tions of the first hymn of the Rig Veda, showing how his approach to translating the Veda changed over the years. Commentaries and Annotated Translations: Pieces from Sri Aurobindo’s manuscripts in which he commented on hymns to Agni or provided annotated translations of them. Some translations of hymns addressed to Agni are included in The Secret of the Veda, volume 15 of THE COMPLETE WORKS OF SRI AUROBINDO. That volume consists of all Sri Aurobindo’s essays on and translations of Vedic hymns that appeared first in the monthly review Arya between 1914 and 1920. His writings on the Veda that do not deal primarily with Agni and that were not published in the Arya are collected in Vedic and Philological Studies, volume 14 of THE COMPLETE WORKS. -

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, Volume 4

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, Volume 4 This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, Volume 4 Books 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 and 18 Translator: Kisari Mohan Ganguli Release Date: March 26, 2005 [EBook #15477] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MAHABHARATA VOL 4 *** Produced by John B. Hare. Please notify any corrections to John B. Hare at www.sacred-texts.com The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa BOOK 13 ANUSASANA PARVA Translated into English Prose from the Original Sanskrit Text by Kisari Mohan Ganguli [1883-1896] Scanned at sacred-texts.com, 2005. Proofed by John Bruno Hare, January 2005. THE MAHABHARATA ANUSASANA PARVA PART I SECTION I (Anusasanika Parva) OM! HAVING BOWED down unto Narayana, and Nara the foremost of male beings, and unto the goddess Saraswati, must the word Jaya be uttered. "'Yudhishthira said, "O grandsire, tranquillity of mind has been said to be subtile and of diverse forms. I have heard all thy discourses, but still tranquillity of mind has not been mine. In this matter, various means of quieting the mind have been related (by thee), O sire, but how can peace of mind be secured from only a knowledge of the different kinds of tranquillity, when I myself have been the instrument of bringing about all this? Beholding thy body covered with arrows and festering with bad sores, I fail to find, O hero, any peace of mind, at the thought of the evils I have wrought. -

Asian and African Civilizations: Course Description, Topical Outline, and Sample Unit. INSTITUTION Columbia Univ., New York, NY

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 423 174 SO 028 555 AUTHOR Beaton, Richard A. TITLE Asian and African Civilizations: Course Description, Topical Outline, and Sample Unit. INSTITUTION Columbia Univ., New York, NY. Esther A. and Joseph Klingenstein Center for Independent School Education. PUB DATE 1995-00-00 NOTE 294p.; Photographs and illustrations may not reproduce well. AVAILABLE FROM Esther A. and Joseph Klingenstein Center for Independent School Education, Teachers College, Columbia University, 525 West 120th Street, Box 125, New York, NY, 10027. PUB TYPE Dissertations/Theses Practicum Papers (043) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *African Studies; *Asian Studies; Course Content; *Course Descriptions; Ethnic Groups; Foreign Countries; *Indians; Non Western Civilization; Secondary Education; Social Studies; World History IDENTIFIERS Africa; Asia; India ABSTRACT This paper provides a skeleton of a one-year course in Asian and African civilizations intended for upper school students. The curricular package consists of four parts. The first part deals with the basic shape and content of the course as envisioned. The remaining three parts develop a specific unit on classical India with a series of teacher notes, a set of student readings that can be used according to individual needs, and a prose narrative of content with suggestions for extension and inclusion. (EH) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be z:Lad *s from the original document. -

The Buddha and His Predecessors

7/2/2020 THE BUDDHA AND HIS PREDECESSORS THE BUDDHA AND HIS PREDECESSORS inindianculture.com/ BOOK I : Siddharth Gautama—How a Bodhisatta became the Buddha PART V: THE BUDDHA AND HIS PREDECESSORS The Buddha and the Vedic Rishis 1. The Vedas are a collection of Mantras, i.e., hymns or chants. The reciters of these hymns are called Rishis. 2. The Mantras are mere invocations to deities such as Indra, Varuna, Agni, Soma, Isana, Prajapati, Bramba, Mahiddhi, Yama and others. 3. The invocations are mere prayers for help against enemies, for gift of wealth, for accepting the offerings of food, flesh and wine from the devotee. https://www.printfriendly.com/p/g/Ng9vN8 1/11 7/2/2020 THE BUDDHA AND HIS PREDECESSORS 4. There is not much philosophy in the Vedas. But there were some Vedic sages who had entered into speculations of a philosophical nature. 5. These Vedic sages were : (1) Aghamarsana; (2) Prajapati Parmesthin; (3) Brahmanaspati, otherwise known as Brihaspati; (4) Anila; (5) Dirghatamas; (6) Narayan; (7) Hiranyagarbha; and (8) Visvakar-man. 6. The main problems of these Vedic philosophers were: How did the world originate ? In what manner were individual things created ? Why have they their unity and existence ? Who created, and who ordained ? From what did the world spring up and to what again will it return ? 7. Aghamarsana said that the world was created out of Tapas (heat). Tapas was the creative principle from which eternal law and truth were born. From these were produced the night (tamas). Tamas produced water and from water originated time.