Mapping the Chronology of Bhakti Milestones, Stepping Stones, and Stumbling Stones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swami Vivekananda and Sri Aurobindo Ghosh

UNIT 6 HINDUISM : SWAMI VIVEKANANDA AND SRI AUROBINDO GHOSH Structure 6.2 Renaissance of Hi~~duis~iiand the Role of Sri Raniakrishna Mission 0.3 Swami ViveItananda's Philosopliy of Neo-Vedanta 6.4 Swami Vivckanalida on Nationalism 6.4.1 S\varni Vivcknnnnda on Dcrnocracy 6.4.2 Swami Vivckanar~daon Social Changc 6.5 Transition of Hinduism: Frolii Vivekananda to Sri Aurobindo 6.5. Sri Aurobindo on Renaissance of Hinduism 6.2 Sri Aurol>i~ldoon Evil EffLrcls of British Rulc 6.6 S1.i Aurobindo's Critique of Political Moderates in India 6.6.1 Sri Aurobilido on the Essencc of Politics 6.6.2 SI-iAurobindo oil Nationalism 0.6.3 Sri Aurobindo on Passivc Resistance 6.6.4 Thcory of Passive Resistance 6.6.5 Mcthods of Passive Rcsistancc 6.7 Sri Aurobindo 011 the Indian Theory of State 6.7.1 .J'olitical ldcas of Sri Aurobindo - A Critical Study 6.8 Summary 1 h 'i 6.9 Exercises j i 6.1 INTRODUCTION In 19"' celitury, India camc under the British rule. Due to the spread of moder~ieducation and growing public activities, there developed social awakening in India. The religion of Hindus wns very harshly criticized by the Christian n?issionaries and the British historians but at ~hcsanie timc, researches carried out by the Orientalist scholars revealcd to the world, lhc glorioi~s'tiaadition of the Hindu religion. The Hindus responded to this by initiating reforms in thcir religion and by esfablishing new pub'lie associations to spread their ideas of refor111 and social development anlong the people. -

Companion to Hymns to the Mystic Fire

Companion to Hymns to the Mystic Fire Volume III Word by word construing in Sanskrit and English of Selected ‘Hymns of the Atris’ from the Rig-veda Compiled By Mukund Ainapure i Companion to Hymns to the Mystic Fire Volume III Word by word construing in Sanskrit and English of Selected ‘Hymns of the Atris’ from the Rig-veda Compiled by Mukund Ainapure • Original Sanskrit Verses from the Rig Veda cited in The Complete Works of Sri Aurobindo Volume 16, Hymns to the Mystic Fire – Part II – Mandala 5 • Padpātha Sanskrit Verses after resolving euphonic combinations (sandhi) and the compound words (samās) into separate words • Sri Aurobindo’s English Translation matched word-by-word with Padpātha, with Explanatory Notes and Synopsis ii Companion to Hymns to the Mystic Fire – Volume III By Mukund Ainapure © Author All original copyrights acknowledged April 2020 Price: Complimentary for personal use / study Not for commercial distribution iii ॥ी अरिव)दचरणारिव)दौ॥ At the Lotus Feet of Sri Aurobindo iv Prologue Sri Aurobindo Sri Aurobindo was born in Calcutta on 15 August 1872. At the age of seven he was taken to England for education. There he studied at St. Paul's School, London, and at King's College, Cambridge. Returning to India in 1893, he worked for the next thirteen years in the Princely State of Baroda in the service of the Maharaja and as a professor in Baroda College. In 1906, soon after the Partition of Bengal, Sri Aurobindo quit his post in Baroda and went to Calcutta, where he soon became one of the leaders of the Nationalist movement. -

(Rjelal) Magic Consciousness and Life Negation of Sri

Research Journal of English Language and Literature (RJELAL) A Peer Reviewed (Refereed) International Vol.3.3.2015 (July-Sep) Journalhttp://www.rjelal.com RESEARCH ARTICLE MAGIC CONSCIOUSNESS AND LIFE NEGATION OF SRI AUROBINDO’S SELECT POEMS S.KARTHICK1, Dr. O.T. POONGODI2 1(Ph.D) Research Scholar, R & D Cell, Bharathiar Universty, Coimbatore. 2Assistant Professor of English, Thiruvalluvar Govt. Arts College Rasipuram. ABSTRACT Magic consciousness and Life Negation are the divine inclination principle of human being. Spiritual practice made to uplift their eternal journey. It had nothing to do with materialistic worshippers. The dawn of the higher or undivided magic consciousness is only for the super-men who had the right to enter into communion soul with the supra- sensuous. The aim of this paper is to through the light on sacred essence of Sri Aurobindo’s select poems. Under this influences one of the popular imaginations of Atman for the immaterial part of the individual. S.KARTHICK Aurobindo’s poetry asserts that the illuminating hidden meaning of the Vedas. It brings untrammeled inner reflection of the Upanishads. The world of life negation comes from supra- sensuous. It is a truism that often a long writing of the Vedas has come to practice. The Vedas, Upanishads were only handed down orally. In this context seer poets like Sri Aurobindo has intertwined the secret instruction about the hidden meaning of Magic consciousness and Life negation through his poetry. Key words: Supra- Sensuous, Mythopoeic Visionary and Atman. ©KY PUBLICATIONS INTRODUCTION inner truth of Magic consciousness and Life negation “The force varies always according to the cannot always be separated from the three co- power of consciousness which it related aspects of Mystical, Philosophy and Ecstatic. -

Institute of Human Study Hyderabad

A Journal of Integral and Future Studies Published by Institute of Human Study Hyderabad Volume IVi Issue II Volume IV Issue II NEW RACE is published by Chhalamayi Reddy on behalf of Institute of Human Study, 2-2-4/1, O.U.Road, Hyderabad 500 044. Founder Editor : (Late) Prof. V. Madhusudan Reddy Editor-in-Chief: V. Ananda Reddy Assistant Editor: Shruti Bidwaikar Designing: Vipul Kishore Email: [email protected]; Phone: 040 27098414 On the web: www.instituteofhumanstudy.org ISSN No.: 2454–1176 ii Volume IV Issue II NEW RACE A Journal of Integral & Future Studies August 2018 Volume IV Issue 2 CONTENTS From the Editor's Desk... Section II: Beauty and Delight 36 Shruti Bidwaikar iv Beauty in Women Sri Aurobindo 37 Section I: Truth 1 Laxmiben Patel’s Work Swami Vivekananda: with the Mother “A Soul of Puissance” Deepshikha Reddy 39 Sri Aurobindo 2 The First Flight... (a sketch) “I had some Strange Power” Deepshikha Reddy 42 Swami Vivekananda 4 Towards a Theory of Poetic Creation Sri Aurobindo: Vinod Balakrishnan 43 Bridge between the Section III: Life 47 Past and the Future The Finnish Education Model: M. P. Pandit 7 In the Light of the Mother’s Essays on Education Significance of Sridarshan Koundinya 48 Sri Aurobindo’s Relics Self-Determination and Ananda Reddy 15 the Path Ahead Evolution Next Kisholoy Gupta 53 Alok Pandey 26 Coming in the Clasp of Divine Grace Search for the Unity of Dolan 57 Matter and Energy Sketches of Life Narendra Joshi 31 Oeendrila Guha 59 iii Volume IV Issue II From the Editor's Desk.. -

“The Theory of Political Resistance - a Review & Dr

Vol. 4(6), pp. 187-192, July 2016 DOI: 10.14662/IJPSD2016.019 International Journal of Copy©right 2016 Political Science and Author(s) retain the copyright of this article ISSN: 2360-784X Development http://www.academicresearchjournals.org/IJPSD/Index.html Full Length Research “The Theory of Political Resistance - A Review & Dr. B.R. Ambedkar‟s Approach” Mr. Vishal Lahoo Kamble Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Dr. Ptangrao Kadam Arts & Commerce College, Pen. Dist- Raigad.( Maharashtra), India. E- Mail: [email protected] Accepted 12 June 2016 The Resistance, woes of an individual can be made general and by raising a collective struggle movement it can be redressed. It means resistance is an in born tool humans have obtained. The reaction of resistance is made clear by biology. The ancient times in India, such theory of resistance was laid down, for the first time, by Gautama Buddha. Dr. Babasaheb Amdedkar, who was generally influenced by the philosophical thought of Gautama Buddha raised a movement against the established, traditional social system which had inflicted in justices on so called untouchable, down- trodden castes, for the purpose of getting them the human right and human values. His movement was of social and political nature, through which, he accepted the waddle way expected by Gautama Buddha and thus, put forth his theory of social and political resistance. In the modern times western thinkers also have Henry Thoreau‟s expressed the concept of civil disobedience through the feeling of resistance. Tolstoy was another philosopher who professed philosophy of resistance through (insistence on truth) and non-co-operation. -

Books on and by Bal Gangadhar Tilak (Birth Anniversary on 23Rd July

Books on and by Bal Gangadhar Tilak (Birth Anniversary on 23rd July) (English Books) Sr. Title Author Publisher and Year of No. Address Publication 1. Vedic chronology and Bal Gangadhar Messers Tilak Bros., 1925 vedanga jyotisha Tilak Poona 2. Srimad Bhagavadgita Bal Gangadhar R.B. Tilak, 1935 rahasya or Karma-yoga- Tilak Lokamanya Tilak sastra. Mandir, Poona 3. Lokmanya Tilk: Father of D.V. Tahmankar John Murray, 1956 Indian unrest and maker London of modern India 4. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: a D.P. Karmarkar Popular Book 1956 study Depot, Bombay 5. Lokmanya Tilak: a Ram Gopal Asia Publishing 1956 Biography House, Bombay 6. Lok many Bal Gangadhar S.L. Karandikar, ---- 1957 Tilak; the Hercules and Prometheus of modern India 7. Lokamanya Tilak; a G.P. and Bhagwat, Jaico Publishing 1959 biography A.K. Pradhan House, Bombay 8. Lokamanya N.G. Jog Ministry of 1962 Balgangadhar Tilak Information and Broadcasting, New Delhi 9. Tilak and Gokhale: Stanley A. Wolpert University of 1962 revolution and reform in California Press , the making of modern Berkeley India 10. Letters of Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Kesari Prakashan, 1966 Tilak Tilak Poona 11. Tilak and the struggle for Reisner, I.M. and People’s publication 1966 Indian freedom Goldberg, N.M. House, New Delhi 12. Lokamanya Tilak: father Dhananjay Keer Popular Prakashan, 1969 of the Indian freedom Bombay struggle 13. Bal Gangadhar Tilak: a T.V. Parvate Navajivan 1972 narrative and Publishing House, interpretative review of Ahmedabad his life, career and contemporary events 14. The myth of the Richard I. Cashman University of 1975 Lokamanya California Press, California 15. -

An Indian Aesthetic Consciousness of Natural Corollary in Sri Aurobindo's

An Indian Aesthetic Consciousness of Natural Corollary in Sri Aurobindo’s Select Poems S. Karthick (Ph.D.) Research Scholar R&D Cell, Bharathiar University Coimbatore & Dr. O. T. Poongodi Assistant Professor of English, Thiruvalluvar Govt. Arts College Rasipuram India ABSTRACT Eco aesthetic is a critical mode of English poetry in Indian aesthetics. It has a poise of nature consciousness of spiritual unity. Nature literature aims at a rational conception of the reality as a whole. It seeks to gain true insight into the general structure of the universe and man‟s relation to nature. The aim of this paper is to examine Sri Aurobindo‟s shorter lyrics, in particular, the glimpses of nature in Indian aesthetic realization. This purpose of eco- centric view of literature is not to place some high alien aim before man and nature. It has to uncover the ultimate purpose of human being. In this, nature is seeking unconscious transformation of one being with universe. Sri Aurobindo‟s aesthetic natural lyrics speak to the cosmic consciousness of delight. The natural identity of the soul that has the eternal value of supreme one and it carries the experience of life and death from birth to birth, the soul that connects the sequence of experiences. This versus in Indian aesthetics is celebrating the immortal in nature and it evokes the eternal relationship towards human. Key Words: Cosmic consciousness, Supramental, Supreme soul. INTRODUCTION Despite of an important note India is a knowledgeable society of eco- centric view. Indian aesthetic has been sharing its knowledge in a way of understandable to both a philosopher and a common man. -

Download Book

TEXT FLY WITHIN THE BOOK ONLY J< OU_1 58876 >[g Publishers: SRI AUROBINDO ASHRAM PONDICHERRY All rights reserved First Edition, November 1940 Second Edition, March 1947 Third Edition, January 1955 SRI AUROBINDO ASHRAM PRESS PONDICHERRY PRINTED IN INDIA 1025/12/54/1500 CONTENTS Page L BANDE MATARAM .... i II. RISHI . BANKIM CHANDRA . 7 III. BAL GANGADHAR TILAK ... 14 IV. DAYANANDA (i) The Man and His Wosk . 39 xXii) Dayananda and the Veda . 48 V. THE MEN THAT PASS . , 6r PUBLISHER'S NOTE Our acknowledgements are due to Messrs. Gancsh & Go, and to the Editor of the Vcdic Magazine for permission to reprint the appreciation of Tilak, which was written as a foreword to the Speeches of Bal Gangadhar Tilak and the articles on Dayananda. BANKIM-TILAK-DAYANANDA BANDE MATARAM (Original Bengali in Devanagri Character) -^^ Ptd II BANKIM TILAK DAYANANDA gfir *TT frf ^TT'ff Hld<H II BANDE MATARAM (Translation} Mother, I bow to thee! Rich with thy hurrying streams. Bright with thy orchard gleams. Cool with thy winds of delight, Dark fields waving. Mother of might, Mother free. Glory of moonlight dreams, Over thy branches and lordly streams, Clad in thy blossoming trees, Mother, giver of ease, Laughing low and sweet! Mother, I kiss thy feet, Speaker sweet and low! Mother, to thee I bow. Who hath said thou art weak in thy lands, When the swords flash out in twice seventy million hands And seventy million voices roar Thy dreadful name from shore to shore? With many strengths who art mighty and stored, BANKIM TILAK DAYANANDA To thee I call. -

Sri Aurobindo's Thesis on Resistance Passive Or Active

EUROPEAN ACADEMIC RESEARCH, VOL. I, ISSUE 5/ AUGUST 2013 ISSN 2286-4822, www.euacademic.org IMPACT FACTOR: 0.485 (GIF) Sri Aurobindo’s Thesis on Resistance Passive or Active DEBASHRI BANERJEE Chatra Ramai Pandit Mahavidyalaya Bankura, West Bengal India Abstract: Theory regarding consciousness is a very debatable concept. In Western psychology, consciousness becomes similar with the mental side of consciousness, while in Indian psychology it seems equal to that of the soul. In sri aurobindian psychology I want to focus the entire discussion on whether consciousness is mental or spiritual in nature. Key words: Sri Aurobindo, theory of consciousness, mental consciousness, spiritual consciousness, the soul, the mind. Introduction In the social-political theory of Sri Aurobindo swaraj seems to be the beginning of Life Divine and boycott as one of its important corollaries. In his spiritual dream of fulfilling the union with the Divine, he had taken the political path as he truly realized that for making our country wholly prepared for this spiritual destination, our first priority must be the attainment of its political freedom. Political liberty, in his opinion, serves as the gateway of achieving the spiritual liberty. He had a firm belief over India’s spiritual excellence and for making our beloved mother-land as the spiritual guide of all other spiritually backward nations it has to be made free from the shackles of its political servitude. Boycott is actually treated as an excellent weapon in this regard. In this context the question of passive as well as active resistances arise instantly. 569 Debashri Banerjee – Sri Aurobindo’s Thesis on Resistance: Passive or Active The concepts of passive and active resistances arise as the two important corollaries of the boycott agitation. -

The Renaissance in India

20 The Renaissance in India and Other Essays on Indian Culture VOLUME 20 THE COMPLETE WORKS OF SRI AUROBINDO © Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust 1997 Published by Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department Printed at Sri Aurobindo Ashram Press, Pondicherry PRINTED IN INDIA The Renaissance in India with A Defence of Indian Culture Publisher's Note Most of the essays that make up this volume have appeared until now under the title The Foundations of Indian Culture. That title was not Sri Aurobindo's. It was ®rst used when those essays were published as a book in New York in 1953. The present volume consists of three series of essays and one single essay, published in the monthly review Arya as follows: The Renaissance in India, August ± November 1918. Indian Culture and External In¯uence, March 1919. ªIs India Civilised?º, December 1918 ± February 1919. A Defence of Indian Culture, February 1919 ± January 1921. Sri Aurobindo revised the four essays making up The Renais- sance in India and published them as a booklet in 1920. He later revised ªIs India Civilised?º and the ®rst eight and a half chapters of A Defence of Indian Culture. These revised chapters were not published during his lifetime. In 1947 some of the later chapters of A Defence of Indian Culture, lightly revised, were published in two booklets. The four essays on Indian art appeared as The Signi®cance of Indian Art and the four essays on Indian polity as The Spirit and Form of Indian Polity. The rest of the series was only sporadically revised. -

Vishva Vaishnava Raj Sabha World Vaishnava Association

VISHVA VAISHNAVA RAJ SABHA WORLD VAISHNAVA ASSOCIATION A Study about the Past, Present & Future of the World Vaishnava Association SWAMI B.A. P ARAMADVAITI PUBLISHED FOR THE World Vaishnava Association by The Vrindavan Institute for Vaishnava Culture and Studies 169 Bhut Galli, near Gopeswara Mahadev 281121 Vrindavan, District Mathura - U.P. INDIA phone: +91 (0) 565 443 623 e-mail: [email protected] web-site: www.vrindavan.org FOR FURTHER INFORMATIONS YOU MAY ALSO CONTACT : WVA-Office India Vanshi Kunja, Gopeswara Road 146 281121 Vrindavan, District Mathura - U.P. phone: +91 (0) 565 443 932 fax: +91 (0) 565 442 172 e-mail: [email protected] web-site: www.wva-vvrs.org All rights reserved by the Supreme Lord. Readers are encouraged to distribute information contained within this book in any way possible; duly citing the source. First Edition ISBN: 81-901600-0-1 Printed in India CONTENTS Preface ............................................................................. 7 Introduction by Acharya D.A., Secretary of the WVA ...................11 SRI SIKSHASTAKAM ................................................................................. 21 by Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu THE SPIRIT OF THE WORLD VAISHNAVA ASSOCIATION .......................... 25 by Krishna Das Kaviraj Goswami THE GENERAL PRESENTATION OF THE WVA ........................................ 29 THE HISTORY ......................................................................................... 37 THE PRESENT ........................................................................................ -

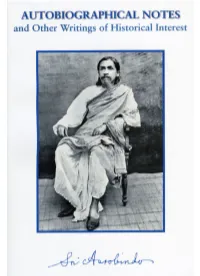

Autobiographical Notes and Other Writings of Historical Interest

VOLUME36 THE COMPLETE WORKS OF SRI AUROBINDO ©SriAurobindoAshramTrust2006 Published by Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department Printed at Sri Aurobindo Ashram Press, Pondicherry PRINTED IN INDIA Autobiographical Notes and Other Writings of Historical Interest Sri Aurobindo in Pondicherry, August 1911 Publisher’s Note This volume consists of (1) notes in which Sri Aurobindo cor- rected statements made by biographers and other writers about his life and (2) various sorts of material written by him that are of historical importance. The historical material includes per- sonal letters written before 1927 (as well as a few written after that date), public statements and letters on national and world events, and public statements about his ashram and system of yoga. Many of these writings appeared earlier in Sri Aurobindo on Himself and on the Mother (1953) and On Himself: Com- piledfromNotesandLetters(1972). These previously published writings, along with many others, appear here under the new title Autobiographical Notes and Other Writings of Historical Interest. Sri Aurobindo alluded to his life and works not only in the notes included in this volume but also in some of the letters he wrote to disciples between 1927 and 1950. Such letters have been included in Letters on Himself and the Ashram, volume 35 of THE COMPLETE WORKS OF SRI AUROBINDO. The autobiographical notes, letters and other writings in- cluded in the present volume have been arranged by the editors in four parts. The texts of the constituent materials have been checked against all relevant manuscripts and printed texts. The Note on the Texts at the end contains information on the people and historical events referred to in the texts.