With Kathleen Thelen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phd in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook

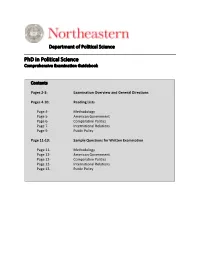

Department of Political Science __________________________________________________________ PhD in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook Contents Pages 2-3: Examination Overview and General Directions Pages 4-10: Reading Lists Page 4- Methodology Page 5- American Government Page 6- Comparative Politics Page 7- International Relations Page 9- Public Policy Page 11-13: Sample Questions for Written Examination Page 11- Methodology Page 12- American Government Page 12- Comparative Politics Page 12- International Relations Page 13- Public Policy EXAMINATION OVERVIEW AND GENERAL DIRECTIONS Doctoral students sit For the comprehensive examination at the conclusion of all required coursework, or during their last semester of coursework. Students will ideally take their exams during the fifth semester in the program, but no later than their sixth semester. Advanced Entry students are strongly encouraged to take their exams during their Fourth semester, but no later than their FiFth semester. The comprehensive examination is a written exam based on the literature and research in the relevant Field of study and on the student’s completed coursework in that field. Petitioning to Sit for the Examination Your First step is to petition to participate in the examination. Use the Department’s graduate petition form and include the following information: 1) general statement of intent to sit For a comprehensive examination, 2) proposed primary and secondary Fields areas (see below), and 3) a list or table listing all graduate courses completed along with the Faculty instructor For the course and the grade earned This petition should be completed early in the registration period For when the student plans to sit For the exam. -

Reviewer Fatigue? Why Scholars PS Decline to Review Their Peers’ Work

AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION Reviewer Fatigue? Why Scholars PS Decline to Review Their Peers’ Work | Marijke Breuning, Jeremy Backstrom, Jeremy Brannon, Benjamin Isaak Gross, Announcing Science & Politics Political Michael Widmeier Why, and How, to Bridge the “Gap” Before Tenure: Peer-Reviewed Research May Not Be the Only Strategic Move as a Graduate Student or Young Scholar Mariano E. Bertucci Partisan Politics and Congressional Election Prospects: Political Science & Politics Evidence from the Iowa Electronic Markets Depression PSOCTOBER 2015, VOLUME 48, NUMBER 4 Joyce E. Berg, Christopher E. Peneny, and Thomas A. Rietz dep1 dep2 dep3 dep4 dep5 dep6 H1 H2 H3 H4 H5 H6 Bayesian Analysis Trace Histogram −.002 500 −.004 400 −.006 300 −.008 200 100 −.01 0 2000 4000 6000 8000 10000 0 Iteration number −.01 −.008 −.006 −.004 −.002 Autocorrelation Density 0.80 500 all 0.60 1−half 400 2−half 0.40 300 0.20 200 0.00 100 0 10 20 30 40 0 Lag −.01 −.008 −.006 −.004 −.002 Here are some of the new features: » Bayesian analysis » IRT (item response theory) » Multilevel models for survey data » Panel-data survival models » Markov-switching models » SEM: survey data, Satorra–Bentler, survival models » Regression models for fractional data » Censored Poisson regression » Endogenous treatment effects » Unicode stata.com/psp-14 Stata is a registered trademark of StataCorp LP, 4905 Lakeway Drive, College Station, TX 77845, USA. OCTOBER 2015 Cambridge Journals Online For further information about this journal please go to the journal website at: journals.cambridge.org/psc APSA Task Force Reports AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION Let’s Be Heard! How to Better Communicate Political Science’s Public Value The APSA task force reports seek John H. -

Varieties of Liberalization and the New Politics of Social Solidarity

Kathleen Thelen Vol.XVIII, No. 66 - 2012 Vol.XVIII, Varieties of Liberalization and the New Politics XXI (73) - 2015 of Social Solidarity 2014. Cambridge University Press. Pages: 251 ISBN: 9781107679566 Are notions of solidarity obsolete in the face of the free market? Is there a single developed capitalism or are there many? Is there a best, most efficient way to delimit the state from the market and the public from the private or are there alternative, equally efficient solutions? Comparative political economy is often based on the premise that the latter is true. In particular, the now classic Varieties of Capitalism (VofC) comparative approach postulates two types of institutional frameworks. The general idea was that each institutional solution generates positive externalities which may or may not be captured by specific solutions in other institutional domains. Therefore, the precondition for economic success of any given country is not any single institutional solution, but rather a consistent approach throughout the political economy cutting through finance, labor markets, education, inter-firm relations etc. The analysis of developed countries revealed two principal types of such institutional consistency – the coordinated market economy (CME) as a more restrictively regulated variety of capitalism and the liberal market economy (LME) as a more flexible variety oriented towards free markets. The CME path to efficiency and growth is based on the formation of specific skills, protected and organized labor markets and long-term bank-centric corporate governance systems. This was considered as an approach of the Scandinavian countries, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Belgium, the Netherlands and Japan. On the other hand, LME countries base their institutional comparative advantage on general skill formation, flexible labor markets with low unionization and short-term oriented corporate governance with predominant stock-market financing. -

Bringing the State Back Into the Varieties of Capitalism and Discourse Back Into the Explanation of Change* by Vivien A

Center for European Studies Program for the Study of Germany and Europe Working Paper Series 07.3 (2007) Bringing the State Back Into the Varieties of Capitalism * And Discourse Back Into the Explanation of Change by Vivien A. Schmidt Jean Monnet Professor of European Integration Department of International Relations, Boston University 152 Bay State Road, Boston MA 02215 Tel: 1 617 3580192; Fax: 1 617 3539290 Email: [email protected] Abstract The Varieties of Capitalism (VoC) literature’s difficulties in accounting for the full diversity of na- tional capitalisms and in explaining institutional change result at least in part from its tendency to downplay state action and from its rather static, binary division of capitalism into two overall systems. This paper argues first of all that by taking state action—used as shorthand for govern- ment policy forged by the political interactions of public and private actors in given institutional contexts—as a significant factor, national capitalisms can be seen to come in at least three varie- ties: liberal, coordinated, and state-influenced market economies. But more importantly, by bring- ing the state back in, we also put the political back into political economy—in terms of policies, political institutional structures, and politics. Secondly, the paper shows that although recent re- visions to VoC that account for change by invoking open systems or historical institutionalist in- *Paper prepared for presentation for the panel: 7-5 “Explaining institutional change in different varieties of capitalism,” of the Annual Meetings of the American Political Science Association (Philadelphia PA, Aug. 31-Sept. 3, 2006). -

Thelen, 1 Curriculum Vitae Kathleen Thelen Ford Professor of Political

Thelen, 1 Curriculum Vitae Kathleen Thelen Ford Professor of Political Science, MIT and Permanent External Scientific Member, Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, Cologne, Germany Address Department of Political Science [email protected] Massachusetts Institute of Technology http://web.mit.edu/polisci/faculty/K.Thelen.html 77 Massachusetts Avenue, E53-470 Cambridge, MA 02139-4307 Education M.A. (1981) and Ph.D. (1987), Political Science, University of California, Berkeley B.A. (1979), Political Science, University of Kansas (university and department honors) Teaching Positions Ford Professor of Political Science, MIT (2009-present) Payson S. Wild Professor of Political Science, Northwestern University (2005-2009) Professor of Political Science, Northwestern University (2004-2005) Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, Northwestern University (1994-2004) Assistant Professor, Department of Politics, Princeton University, 1988-1994 Assistant Professor, Department of Government, Oberlin College, 1987-1988 Other Appointments and Invited Visiting Positions 2012- 2014 Research Fellow, Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung April 2013: Guest scholar, Quality of Government Institute, University of Gothenburg, Sweden Summer 2011: Guest scholar, Institute for Advanced Study Berlin (Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin) and Science Center (Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung) Summer 2010: Visiting Professor, Sciences Po, Paris 2007-2011: Senior Research Fellow at Nuffield College, Oxford University, Oxford UK -

Historical Institutionalism and the Welfare State

Historical Institutionalism and the Welfare State Oxford Handbooks Online Historical Institutionalism and the Welfare State Julia Lynch and Martin Rhodes The Oxford Handbook of Historical Institutionalism Edited by Orfeo Fioretos, Tulia G. Falleti, and Adam Sheingate Print Publication Date: Mar 2016 Subject: Political Science, Comparative Politics, Political Institutions Online Publication Date: May 2016 DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199662814.013.25 Abstract and Keywords This chapter examines how historical institutionalism has influenced the analysis of welfare state and labor market policies in the rich industrial democracies. Using Lakatos’s concept of the “scientific research program” as a heuristic, the authors explore the development and expansion of historical institutionalism as a predominant approach in welfare state research. Focusing on this tradition’s strong core of actors (academic path- and boundary-setters), rules (methodology and methods), and norms (ontological and epistemological assumptions), they strive to demarcate the terrain of HI within studies of the welfare state, and to reveal the capacity of HI in this field to underpin a robust but flexible and enduring scholarly research program. Keywords: welfare state, Lakatos, research program, historical institutionalism, ideational approaches HISTORICAL institutionalism and the analysis of welfare states (including the ancillary policy domain of the labor market) overlap significantly. More than elsewhere in Political Science and public policy, much single-country, program, and comparative analysis of the welfare state since the 1980s has taken an historical approach (Amenta 2003). Relatedly, some of the major welfare state scholars have also been major historical institutionalism theorists and proponents—most prominently, but not only, Theda Skocpol, Paul Pierson, and Kathleen Thelen. -

American Political Science Review

AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW AMERICAN https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000060 . POLITICAL SCIENCE https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms REVIEW , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at 08 Oct 2021 at 13:45:36 , on May 2018, Volume 112, Issue 2 112, Volume May 2018, University of Athens . May 2018 Volume 112, Issue 2 Cambridge Core For further information about this journal https://www.cambridge.org/core ISSN: 0003-0554 please go to the journal website at: cambridge.org/apsr Downloaded from 00030554_112-2.indd 1 21/03/18 7:36 AM LEAD EDITOR Jennifer Gandhi Andreas Schedler Thomas König Emory University Centro de Investigación y Docencia University of Mannheim, Germany Claudine Gay Económicas, Mexico Harvard University Frank Schimmelfennig ASSOCIATE EDITORS John Gerring ETH Zürich, Switzerland Kenneth Benoit University of Texas, Austin Carsten Q. Schneider London School of Economics Sona N. Golder Central European University, and Political Science Pennsylvania State University Budapest, Hungary Thomas Bräuninger Ruth W. Grant Sanjay Seth University of Mannheim Duke University Goldsmiths, University of London, UK Sabine Carey Julia Gray Carl K. Y. Shaw University of Mannheim University of Pennsylvania Academia Sinica, Taiwan Leigh Jenco Mary Alice Haddad Betsy Sinclair London School of Economics Wesleyan University Washington University in St. Louis and Political Science Peter A. Hall Beth A. Simmons Benjamin Lauderdale Harvard University University of Pennsylvania London School of Economics Mary Hawkesworth Dan Slater and Political Science Rutgers University University of Chicago Ingo Rohlfi ng Gretchen Helmke Rune Slothuus University of Cologne University of Rochester Aarhus University, Denmark D. -

Comparative Political Institutions Political Science 7172 University of Colorado, Boulder Professor Sarah Wilson Sokhey Fall 2019, Mondays, Ketchum 1B-31, 2-4:30Pm

Comparative Political Institutions Political Science 7172 University of Colorado, Boulder Professor Sarah Wilson Sokhey Fall 2019, Mondays, Ketchum 1B-31, 2-4:30pm Office: Ketchum 133 Office phone: 303-492-2985 E-mail: [email protected] Office hours: Mondays, 10am-12pm & by appointment Course Description This course introduces students to academic research in comparative political institutions. We address a wide variety of topics including what it means to study comparative political institutions, regime type, authoritarian institutions, electoral politics, parliamentary and presidential systems, institutions and ethnic politics, and much more. This course is primarily designed to train political science Ph.D. students, although it may be of interest to students in other disciplines. Course Requirements Students are required to read all material before class and come prepared to discuss the material critically. This class is intended to help prepare political science graduate students for their comprehensive exams and to be prepared to conduct their own research including a dissertation project. The reading load is designed to meet these goals. Your grade will be based on the following components: Research Paper 40% Participation 30% total (see breakdown below) 6 weekly reaction papers 30% total (each worth 5%) Research Paper (worth 40% grade) You are required to write a research paper. In most cases, your paper should include an empirical component, but I am open to suggestions about research design or theoretical papers. Please talk to me first if you will not be including an empirical component to your paper to make sure it fits well with the class. There is no required length, but research papers are often in the 20-30 page range. -

Qualitative and Multi-Method Research Fall 2018 | Volume 16 | Number 2

Qualitative and Multi-Method Research Fall 2018 | Volume 16 | Number 2 Inside: Letter from the President (2019-21) Jason Seawright Letter from the Editor Jennifer Cyr Symposium: Critical Deliberations Concerning DA-RT n DA-RT and its Crises Dvora Yanow n Trust, Transparency, and Process Renée Cramer n Not there for the Taking: DA-RT and Policy Research Samantha Majic n DA-RT: Prioritizing the Profession over the Public? Amy Cabrera Rasmussen n Every Reader a Peer Reviewer? DA-RT, Democracy, and Deskilling Peregrine Schwartz-Shea n Data, Transparency, and Political Theory Nancy Hirschmann Debating the Value of DA-RT for Qualitative Research n Unexplored Advantages of DA-RT for Qualitative Research Verónica Pérez Betancur, Rafael Piñeiro, and Fernando Rosenblatt n The Penumbra of DA-RT: Transparency, Opacity, Normativity: A Response to Pérez Bentancur, Piñeiro Rodríguez, and Rosenblatt Diego Rossello n A Response to Rossello Verónica Pérez Betancur, Rafael Piñeiro, and Fernando Rosenblatt Article n The Reshaping of the Quantitative-Qualitative Divide: A Case of QCA Dawid Tatarczyk Longform APSA awards Qualitative & Multi-Method Research Fall 2018 | Volume 16 | Number 2 Table of Contents Letter from the President (2019-21) Jason Seawright - https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3524428 ............................................ ii Letter from the Editor Jennifer Cyr - https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3524430 ..................................................iii Symposium: Critical Deliberations Concerning DA-RT DA-RT and its Crises Dvora Yanow - https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3524267 ............................................... 1 Trust, Transparency, and Process Renée Cramer - https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3524289 ............................................ 10 Not there for the Taking: DA-RT and Policy Research Samantha Majic - https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3524305 ......................................... -

Gender in the Journals: Publication Patterns in Political Science

......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... THE PROFESSION ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Gender in the Journals: Publication Patterns in Political Science Dawn Langan Teele, University of Pennsylvania Kathleen Thelen, Massachusetts Institute of Technology ABSTRACT This article explores publication patterns across 10 prominent political science journals, documenting a significant gender gap in publication rates for men and women. We present three broad findings.First , we find no evidence that the low percentage of female authors simply mirrors an overall low share of women in the profession. Instead, we find continued underrepresentation of women in many of the discipline’s top jour- nals. Second, we find that women are not benefiting equally in a broad trend across the discipline toward coauthorship. Most published collaborative research in these journals emerges from all-male teams. Third, it appears that the methodological proclivities of the top journals do not fully reflect the kind of work -

Talkin' Bout Digitalization

Talkin’ bout Digitalization A Comparative Analysis of National Discourses on the Digital Future of Work Matteo Marenco1 Timo Seidl2 20 April, 2021 Abstract New forms of work intermediation - the gig economy - and the growing use of advanced digital technologies - the new knowledge economy - are changing the nature of work. The digitalization of work, however, is shaped by how countries respond to it. But how countries respond to digitalization, we argue, depends on how digitalization is perceived in the first place. Using text-as-data methods on a novel corpus of translated newspaper and policy documents from eight European countries as well as qualitative evidence from interviews and secondary sources, we show that there are clear country effects in how dig- italization is framed and fought over. Drawing on discursive-institutionalist and coalitional approaches, we argue that institutional differences explain these discursive differences by structuring interpretative struggles in favor of the social coalitions that support them. Actors, however, can also challenge these institutions by using the discursive agency to change these underlying support coalitions. 1 Scuola Normale Superiore 2 Centre for European Integration Research, University of Vienna We would like to thank Dorothee Bohle, Guglielmo Meardi, and the participants of the ECPRpanel on the Politics, Governance and Regulation of Big Transformations for helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper. Talkin’ about Digitalization Introduction From manufacturing goods to building relationships, from daily business to everyday life, from credit scores to social scores: digital technologies are rapidly transforming the way we live our lives and run our economies. But digitalization is no force of nature. -

Why and How Public Officials Resist the Law

Florida State University Law Review Volume 40 Issue 3 Article 4 2013 Dissenting from Within: Why and How Public Officials Resist the Law Adam Shinar Harvard Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Adam Shinar, Dissenting from Within: Why and How Public Officials Resist the Law, 40 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 601 (2013) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol40/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW DISSENTING FROM WITHIN: WHY AND HOW PUBLIC OFFICIALS RESIST THE LAW Adam Shinar VOLUME 40 SPRING 2013 NUMBER 3 Recommended citation: Adam Shinar, Dissenting from Within: Why and How Public Officials Resist the Law, 40 FLA. ST. U. L. REV. 601 (2013). DISSENTING FROM WITHIN: WHY AND HOW PUBLIC OFFICIALS RESIST THE LAW ADAM SHINAR ABSTRACT This Article examines why and how public officials consciously resist the laws and poli- cies they are in charge of implementing. The Article argues that this phenomenon is not an anomaly, but rather pervasive and unavoidable. It occurs in all government institutions and is facilitated by the same structures that are designed to promote compliance. The Article attempts to uncover the causes which render official resistance possible, arguing that resistance can be traced both to the limits inherent in the rule of law and to problems of institutional design.