PPM 504: Perspectives on Institutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analyzing Change in International Politics: the New Institutionalism and the Interpretative Approach

Analyzing Change in International Politics: The New Institutionalism and the Interpretative Approach - Guest Lecture - Peter J. Katzenstein* 90/10 This discussion paper was presented as a guest lecture at the MPI für Gesellschaftsforschung, Köln, on April 5, 1990 Max-Planck-Institut für Gesellschaftsforschung Lothringer Str. 78 D-5000 Köln 1 Federal Republic of Germany MPIFG Discussion Paper 90/10 Telephone 0221/ 336050 ISSN 0933-5668 Fax 0221/ 3360555 November 1990 * Prof. Peter J. Katzenstein, Cornell University, Department of Government, McGraw Hall, Ithaca, N.Y. 14853, USA 2 MPIFG Discussion Paper 90/10 Abstract This paper argues that realism misinterprets change in the international system. Realism conceives of states as actors and international regimes as variables that affect national strategies. Alternatively, we can think of states as structures and regimes as part of the overall context in which interests are defined. States conceived as structures offer rich insights into the causes and consequences of international politics. And regimes conceived as a context in which interests are defined offer a broad perspective of the interaction between norms and interests in international politics. The paper concludes by suggesting that it may be time to forego an exclusive reliance on the Euro-centric, Western state system for the derivation of analytical categories. Instead we may benefit also from studying the historical experi- ence of Asian empires while developing analytical categories which may be useful for the analysis of current international developments. ***** In diesem Aufsatz wird argumentiert, daß der "realistische" Ansatz außenpo- litischer Theorie Wandel im internationalen System fehlinterpretiere. Dieser versteht Staaten als Akteure und internationale Regime als Variablen, die nationale Strategien beeinflussen. -

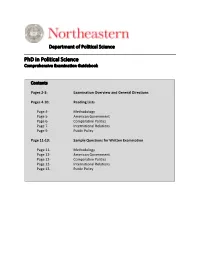

Phd in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook

Department of Political Science __________________________________________________________ PhD in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook Contents Pages 2-3: Examination Overview and General Directions Pages 4-10: Reading Lists Page 4- Methodology Page 5- American Government Page 6- Comparative Politics Page 7- International Relations Page 9- Public Policy Page 11-13: Sample Questions for Written Examination Page 11- Methodology Page 12- American Government Page 12- Comparative Politics Page 12- International Relations Page 13- Public Policy EXAMINATION OVERVIEW AND GENERAL DIRECTIONS Doctoral students sit For the comprehensive examination at the conclusion of all required coursework, or during their last semester of coursework. Students will ideally take their exams during the fifth semester in the program, but no later than their sixth semester. Advanced Entry students are strongly encouraged to take their exams during their Fourth semester, but no later than their FiFth semester. The comprehensive examination is a written exam based on the literature and research in the relevant Field of study and on the student’s completed coursework in that field. Petitioning to Sit for the Examination Your First step is to petition to participate in the examination. Use the Department’s graduate petition form and include the following information: 1) general statement of intent to sit For a comprehensive examination, 2) proposed primary and secondary Fields areas (see below), and 3) a list or table listing all graduate courses completed along with the Faculty instructor For the course and the grade earned This petition should be completed early in the registration period For when the student plans to sit For the exam. -

Theda Skocpol

NAMING THE PROBLEM What It Will Take to Counter Extremism and Engage Americans in the Fight against Global Warming Theda Skocpol Harvard University January 2013 Prepared for the Symposium on THE POLITICS OF AMERICA’S FIGHT AGAINST GLOBAL WARMING Co-sponsored by the Columbia School of Journalism and the Scholars Strategy Network February 14, 2013, 4-6 pm Tsai Auditorium, Harvard University CONTENTS Making Sense of the Cap and Trade Failure Beyond Easy Answers Did the Economic Downturn Do It? Did Obama Fail to Lead? An Anatomy of Two Reform Campaigns A Regulated Market Approach to Health Reform Harnessing Market Forces to Mitigate Global Warming New Investments in Coalition-Building and Political Capabilities HCAN on the Left Edge of the Possible Climate Reformers Invest in Insider Bargains and Media Ads Outflanked by Extremists The Roots of GOP Opposition Climate Change Denial The Pivotal Battle for Public Opinion in 2006 and 2007 The Tea Party Seals the Deal ii What Can Be Learned? Environmentalists Diagnose the Causes of Death Where Should Philanthropic Money Go? The Politics Next Time Yearning for an Easy Way New Kinds of Insider Deals? Are Market Forces Enough? What Kind of Politics? Using Policy Goals to Build a Broader Coalition The Challenge Named iii “I can’t work on a problem if I cannot name it.” The complaint was registered gently, almost as a musing after-thought at the end of a June 2012 interview I conducted by telephone with one of the nation’s prominent environmental leaders. My interlocutor had played a major role in efforts to get Congress to pass “cap and trade” legislation during 2009 and 2010. -

Measuring the Research Productivity of Political Science Departments Using Google Scholar

The Profession ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Measuring the Research Productivity of Political Science Departments Using Google Scholar Michael Peress, SUNY–Stony Brook ABSTRACT This article develops a number of measures of the research productivity of politi- cal science departments using data collected from Google Scholar. Departments are ranked in terms of citations to articles published by faculty, citations to articles recently published by faculty, impact factors of journals in which faculty published, and number of top pub- lications in which faculty published. Results are presented in aggregate terms and on a per-faculty basis. he most widely used measure of the quality of of search results, from which I identified publications authored political science departments is the US News and by that faculty member, the journal in which the publication World Report ranking. It is based on a survey sent appeared (if applicable), and the number of citations to that to political science department heads and direc- article or book. tors of graduate studies. Respondents are asked to I constructed four measures for each faculty member. First, Trate other political science departments on a 1-to-5 scale; their I calculated the total number of citations. This can be -

Reviewer Fatigue? Why Scholars PS Decline to Review Their Peers’ Work

AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION Reviewer Fatigue? Why Scholars PS Decline to Review Their Peers’ Work | Marijke Breuning, Jeremy Backstrom, Jeremy Brannon, Benjamin Isaak Gross, Announcing Science & Politics Political Michael Widmeier Why, and How, to Bridge the “Gap” Before Tenure: Peer-Reviewed Research May Not Be the Only Strategic Move as a Graduate Student or Young Scholar Mariano E. Bertucci Partisan Politics and Congressional Election Prospects: Political Science & Politics Evidence from the Iowa Electronic Markets Depression PSOCTOBER 2015, VOLUME 48, NUMBER 4 Joyce E. Berg, Christopher E. Peneny, and Thomas A. Rietz dep1 dep2 dep3 dep4 dep5 dep6 H1 H2 H3 H4 H5 H6 Bayesian Analysis Trace Histogram −.002 500 −.004 400 −.006 300 −.008 200 100 −.01 0 2000 4000 6000 8000 10000 0 Iteration number −.01 −.008 −.006 −.004 −.002 Autocorrelation Density 0.80 500 all 0.60 1−half 400 2−half 0.40 300 0.20 200 0.00 100 0 10 20 30 40 0 Lag −.01 −.008 −.006 −.004 −.002 Here are some of the new features: » Bayesian analysis » IRT (item response theory) » Multilevel models for survey data » Panel-data survival models » Markov-switching models » SEM: survey data, Satorra–Bentler, survival models » Regression models for fractional data » Censored Poisson regression » Endogenous treatment effects » Unicode stata.com/psp-14 Stata is a registered trademark of StataCorp LP, 4905 Lakeway Drive, College Station, TX 77845, USA. OCTOBER 2015 Cambridge Journals Online For further information about this journal please go to the journal website at: journals.cambridge.org/psc APSA Task Force Reports AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION Let’s Be Heard! How to Better Communicate Political Science’s Public Value The APSA task force reports seek John H. -

Varieties of Liberalization and the New Politics of Social Solidarity

Kathleen Thelen Vol.XVIII, No. 66 - 2012 Vol.XVIII, Varieties of Liberalization and the New Politics XXI (73) - 2015 of Social Solidarity 2014. Cambridge University Press. Pages: 251 ISBN: 9781107679566 Are notions of solidarity obsolete in the face of the free market? Is there a single developed capitalism or are there many? Is there a best, most efficient way to delimit the state from the market and the public from the private or are there alternative, equally efficient solutions? Comparative political economy is often based on the premise that the latter is true. In particular, the now classic Varieties of Capitalism (VofC) comparative approach postulates two types of institutional frameworks. The general idea was that each institutional solution generates positive externalities which may or may not be captured by specific solutions in other institutional domains. Therefore, the precondition for economic success of any given country is not any single institutional solution, but rather a consistent approach throughout the political economy cutting through finance, labor markets, education, inter-firm relations etc. The analysis of developed countries revealed two principal types of such institutional consistency – the coordinated market economy (CME) as a more restrictively regulated variety of capitalism and the liberal market economy (LME) as a more flexible variety oriented towards free markets. The CME path to efficiency and growth is based on the formation of specific skills, protected and organized labor markets and long-term bank-centric corporate governance systems. This was considered as an approach of the Scandinavian countries, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Belgium, the Netherlands and Japan. On the other hand, LME countries base their institutional comparative advantage on general skill formation, flexible labor markets with low unionization and short-term oriented corporate governance with predominant stock-market financing. -

Theda Skocpol | Mershon Center for International Security Studies | the Ohio State Univ

Theda Skocpol | Mershon Center for International Security Studies | The Ohio State Univ... Page 1 of 2 The Ohio State University www.osu.edu Help Campus map Find people Webmail Search home > events calendar > september 2006 > theda skocpol September Citizenship Lecture Series October Theda Skocpol November December "Voice and Inequality: The Transformation of American Civic Democracy" January Theda Skocpol Professor of Government February Monday, Sept. 25, 2006 and Sociology March Noon Dean of the Graduate Mershon Center for International Security Studies April School of Arts and 1501 Neil Ave., Columbus, OH 43201 Sciences May Harvard University 2007-08 See a streaming video of this lecture. This streaming video requires RealPlayer. If you do not have RealPlayer, you can download it free. Theda Skocpol is the Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology and Dean of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at Harvard University. She has also served as Director of the Center for American Political Studies at Harvard from 1999 to 2006. The author of nine books, nine edited collections, and more than seven dozen articles, Skocpol is one of the most cited and widely influential scholars in the modern social sciences. Her work has contributed to the study of comparative politics, American politics, comparative and historical sociology, U.S. history, and the study of public policy. Her first book, States and Social Revolutions: A Comparative Analysis of France, Russia, and China (Cambridge, 1979), won the 1979 C. Wright Mills Award and the 1980 American Sociological Association Award for a Distinguished Contribution to Scholarship. Her Protecting Soldiers and Mothers: The Political Origins of Social Policy in the United States (Harvard, 1992), won five scholarly awards. -

Bringing the State Back Into the Varieties of Capitalism and Discourse Back Into the Explanation of Change* by Vivien A

Center for European Studies Program for the Study of Germany and Europe Working Paper Series 07.3 (2007) Bringing the State Back Into the Varieties of Capitalism * And Discourse Back Into the Explanation of Change by Vivien A. Schmidt Jean Monnet Professor of European Integration Department of International Relations, Boston University 152 Bay State Road, Boston MA 02215 Tel: 1 617 3580192; Fax: 1 617 3539290 Email: [email protected] Abstract The Varieties of Capitalism (VoC) literature’s difficulties in accounting for the full diversity of na- tional capitalisms and in explaining institutional change result at least in part from its tendency to downplay state action and from its rather static, binary division of capitalism into two overall systems. This paper argues first of all that by taking state action—used as shorthand for govern- ment policy forged by the political interactions of public and private actors in given institutional contexts—as a significant factor, national capitalisms can be seen to come in at least three varie- ties: liberal, coordinated, and state-influenced market economies. But more importantly, by bring- ing the state back in, we also put the political back into political economy—in terms of policies, political institutional structures, and politics. Secondly, the paper shows that although recent re- visions to VoC that account for change by invoking open systems or historical institutionalist in- *Paper prepared for presentation for the panel: 7-5 “Explaining institutional change in different varieties of capitalism,” of the Annual Meetings of the American Political Science Association (Philadelphia PA, Aug. 31-Sept. 3, 2006). -

SIS 802 Comparative Politics

Ph.D. Seminar in Comparative Politics SIS 802, Fall 2016 School of International Service American University COURSE INFORMATION Professor: Matthew M. Taylor Email: [email protected] Classes will be held on Tuesdays, 2:35-5:15pm Office hours: Wednesdays (11:30pm-3:30pm) and by appointment. In the case of appointments, please email me at least two days in advance to schedule. Office: SIS 350 COURSE DESCRIPTION Comparative political science is one of the four traditional subfields of political science. It differs from international relations in its focus on individual countries and regions, and its comparison across units – national, subnational, actors, and substantive themes. Yet it is vital to scholars of international relations, not least because of its ability to explain differences in the basic postures of national and subnational actors, as well as in its focus on key variables of interest to international relations, such as democratization, the organization of state decision-making, and state capacity. Both subfields have benefited historically from considerable methodological and theoretical cross-fertilization which has shaped the study of international affairs significantly. The first section of the course focuses on the epistemology of comparative political science, seeking to understand how we know what we know, the accumulation of knowledge, and the objectivity of the social sciences. The remainder of the course addresses substantive debates in the field, although students are encouraged to critically address the theoretical and methodological approaches that are used to explore these substantive issues. COURSE OBJECTIVES This course will introduce students to the field, analyzing many of the essential components of comparative political science: themes, debates, and concepts, as well as different theoretical and methodological approaches. -

Rewriting the Epic of America

One Rewriting the Epic of America IRA KATZNELSON “Is the traditional distinction between international relations and domes- tic politics dead?” Peter Gourevitch inquired at the start of his seminal 1978 article, “The Second Image Reversed.” His diagnosis—“perhaps”—was mo- tivated by the observation that while “we all understand that international politics and domestic structures affect each other,” the terms of trade across the domestic and international relations divide had been uneven: “reason- ing from international system to domestic structure” had been downplayed. Gourevitch’s review of the literature demonstrated that long-standing efforts by international relations scholars to trace the domestic roots of foreign pol- icy to the interplay of group interests, class dynamics, or national goals1 had not been matched by scholarship analyzing how domestic “structure itself derives from the exigencies of the international system.”2 Gourevitch counseled scholars to turn their attention to the international system as a cause as well as a consequence of domestic politics. He also cautioned that this reversal of the causal arrow must recognize that interna- tional forces exert pressures rather than determine outcomes. “The interna- tional system, be it in an economic or politico-military form, is underdeter- mining. The environment may exert strong pulls but short of actual occupation, some leeway in the response to that environment remains.”3 A decade later, Robert Putnam turned to two-level games to transcend the question as to “whether -

Thelen, 1 Curriculum Vitae Kathleen Thelen Ford Professor of Political

Thelen, 1 Curriculum Vitae Kathleen Thelen Ford Professor of Political Science, MIT and Permanent External Scientific Member, Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, Cologne, Germany Address Department of Political Science [email protected] Massachusetts Institute of Technology http://web.mit.edu/polisci/faculty/K.Thelen.html 77 Massachusetts Avenue, E53-470 Cambridge, MA 02139-4307 Education M.A. (1981) and Ph.D. (1987), Political Science, University of California, Berkeley B.A. (1979), Political Science, University of Kansas (university and department honors) Teaching Positions Ford Professor of Political Science, MIT (2009-present) Payson S. Wild Professor of Political Science, Northwestern University (2005-2009) Professor of Political Science, Northwestern University (2004-2005) Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, Northwestern University (1994-2004) Assistant Professor, Department of Politics, Princeton University, 1988-1994 Assistant Professor, Department of Government, Oberlin College, 1987-1988 Other Appointments and Invited Visiting Positions 2012- 2014 Research Fellow, Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung April 2013: Guest scholar, Quality of Government Institute, University of Gothenburg, Sweden Summer 2011: Guest scholar, Institute for Advanced Study Berlin (Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin) and Science Center (Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung) Summer 2010: Visiting Professor, Sciences Po, Paris 2007-2011: Senior Research Fellow at Nuffield College, Oxford University, Oxford UK -

Historical Institutionalism and the Welfare State

Historical Institutionalism and the Welfare State Oxford Handbooks Online Historical Institutionalism and the Welfare State Julia Lynch and Martin Rhodes The Oxford Handbook of Historical Institutionalism Edited by Orfeo Fioretos, Tulia G. Falleti, and Adam Sheingate Print Publication Date: Mar 2016 Subject: Political Science, Comparative Politics, Political Institutions Online Publication Date: May 2016 DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199662814.013.25 Abstract and Keywords This chapter examines how historical institutionalism has influenced the analysis of welfare state and labor market policies in the rich industrial democracies. Using Lakatos’s concept of the “scientific research program” as a heuristic, the authors explore the development and expansion of historical institutionalism as a predominant approach in welfare state research. Focusing on this tradition’s strong core of actors (academic path- and boundary-setters), rules (methodology and methods), and norms (ontological and epistemological assumptions), they strive to demarcate the terrain of HI within studies of the welfare state, and to reveal the capacity of HI in this field to underpin a robust but flexible and enduring scholarly research program. Keywords: welfare state, Lakatos, research program, historical institutionalism, ideational approaches HISTORICAL institutionalism and the analysis of welfare states (including the ancillary policy domain of the labor market) overlap significantly. More than elsewhere in Political Science and public policy, much single-country, program, and comparative analysis of the welfare state since the 1980s has taken an historical approach (Amenta 2003). Relatedly, some of the major welfare state scholars have also been major historical institutionalism theorists and proponents—most prominently, but not only, Theda Skocpol, Paul Pierson, and Kathleen Thelen.