Building G20 Outreach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Korea-South Korea Relations: Never Mind the Nukes?

North Korea-South Korea Relations: Never Mind The Nukes? Aidan Foster-Carter Leeds University, UK Almost a year after charges that North Korea has a second, covert nuclear program plunged the Peninsula into intermittent crisis, inter-Korean ties appear surprisingly unaffected. The past quarter saw sustained and brisk exchanges on many fronts, seemingly regardless of this looming shadow. Although Pyongyang steadfastly refuses to discuss the nuclear issue with Seoul bilaterally, the fact that six-party talks on this topic were held in Beijing in late August – albeit with no tangible progress, nor even any assurance that such dialogue will continue – is perhaps taken (rightly or wrongly) as meaning the issue is now under control. At all events, between North and South Korea it is back to business as usual – or even full steam ahead. While (at least in this writer’s view) closer inter-Korean relations are in themselves a good thing, one can easily imagine scenarios in which this process may come into conflict with U.S. policy. Should the six-party process fail or break down, or if Pyongyang were to test a bomb or declare itself a nuclear power, then there would be strong pressure from Washington for sanctions in some form. Indeed, alongside the six- way process, the U.S. is already pursuing an interdiction policy with its Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI), which Japan has joined but South Korea, pointedly, has not. Relinking of cross-border roads and railways, or the planned industrial park at Kaesong (with power and water from the South), are examples of initiatives which might founder, were the political weather around the Peninsula to turn seriously chilly. -

SYSTEMIC REFORM at a STANDSTILL: a FLOCK of “Gs” in SEARCH of GLOBAL FINANCIAL STABILITY by Roy Culpeper, President, the North-South Institute

SYSTEMIC REFORM AT A STANDSTILL: A FLOCK OF “Gs” IN SEARCH OF GLOBAL FINANCIAL STABILITY by Roy Culpeper, President, The North-South Institute Commonwealth Secretariat/World Bank Conference on Developing Countries and Global Financial Architecture Marlborough House London, 22-23 June 2000 1 SYSTEMIC REFORM AT A STANDSTILL: A FLOCK OF “Gs” IN SEARCH OF GLOBAL FINANCIAL STABILITY by Roy Culpeper, President, The North-South Institute1 Introduction The subject of “Global Governance” became topical in the 1990s with a rash of financial crises, the most far-reaching and dramatic one having started in East Asia in mid-1997 and spread around the world before subsiding during the course of 1999. It is worth recalling, however, that the subject of Global Governance has been a hardy perennial since the breakdown of the original Bretton Woods system a quarter century ago. Its antecedents include the debate on the New International Economic Order in the 1970s; the North-South Summits of the early 1980s; the UNCED negotiations in Rio de Janeiro in 1992; and the chain of ensuing UN conferences throughout the decade – the Vienna conference on Human Rights, the Social Summit at Copenhagen, the Beijing Conference on gender and development, and the Cairo conference on Population and Development. While these discussions have produced a few tangible results, their impact on Global Governance has been minimal. Although it may sound unpleasant to believers in the rationality of a more equitable world order, perhaps a large reason for the failure of these many attempts to reform the global order is that they have been dominated by the poor and the powerless, while the rich and powerful have not been persuaded of the need for significant changes to the status quo. -

International Economic and Financial Cooperation: New Issues, New Actors, New Responses

International Economic and Financial Cooperation: New Issues, New Actors, New Responses Geneva Reports on the World Economy 6 International Center for Monetary and Banking Studies (ICMB) International Center for Monetary and Banking Studies 11 A Avenue de la Paix 1202 Geneva Switzerland Tel (41 22) 734 9548 Fax (41 22) 733 3853 Website: www.icmb.ch © 2004 International Center for Monetary and Banking Studies Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) Centre for Economic Policy Research 90-98 Goswell Road London EC1V 7RR UK Tel: +44 (0)20 7878 2900 Fax: +44 (0)20 7878 2999 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cepr.org British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 1 898128 84 7 International Economic and Financial Cooperation: New Issues, New Actors, New Responses Geneva Reports on the World Economy 6 Peter B Kenen Council on Foreign Relations and Princeton University Jeffrey R Shafer Citigroup and former US Under Secretary of the Treasury Nigel L Wicks CRESTCo and former Head of HM Treasury Charles Wyplosz Graduate Institute of International Studies, Geneva and CEPR ICMB INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR MONETARY AND BANKING STUDIES CIMB CENTRE INTERNATIONAL DETUDES MONETAIRES ET BANCAIRES International Center for Monetary and Banking Studies (ICMB) The International Center for Monetary and Banking Studies was created in 1973 as an inde- pendent, non-profit foundation. It is associated with Geneva’s Graduate Institute of International Studies. Its aim is to foster exchange of views between the financial sector, cen- tral banks and academics on issues of common interest. -

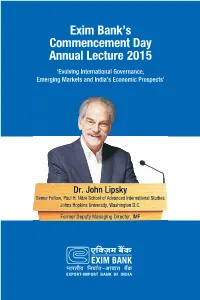

Exim Bank's Commencement Day Annual Lecture 2015

Exim Bank’s Commencement Day Annual Lecture 2015 ‘Evolving International Governance, Emerging Markets and India’s Economic Prospects’ Dr. John Lipsky Senior Fellow, Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies Johns Hopkins University, Washington D.C. Former Deputy Managing Director, IMF 101 This is the Thirtieth Exim Bank Commencement Day Annual Lecture, delivered at the Y. B. Chavan Centre, Mumbai - 400 021 on Monday, March 23, 2015. No part of this Lecture may be reproduced without the permission of Export-Import Bank of India. The views and interpretations in this document are those of the author and not ascribable to Export-Import Bank of India. Evolving International Governance, Emerging Markets and India’s Economic Prospects Dr. John Lipsky Senior Fellow Foreign Policy Institute The Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies Johns Hopkins University Washington, DC I’m honoured to be speaking today at this important event sponsored by EXIM Bank - an institution that is playing a key role in promoting India’s trading relationships with partners around the world - and I would like to thank the management of EXIM for the opportunity to be here. Of course, EXIM Bank’s kind invitation to be the 2015 Commencement Speaker led me to look back at the institution’s history. I found it somewhat surprising that the institution commenced operations just 33 years ago. Perhaps the promotion of India’s international commercial relations previously hadn’t seemed so central to India’s future progress and prosperity, as it does today. Of course, it is sobering, daunting, but also amazing and energizing to realize how much has changed in just that relatively brief span since EXIM’s founding. -

References--391-406 8/12/04 11:33 AM Page 391

11--References--391-406 8/12/04 11:33 AM Page 391 References Aghion, Philippe, Philippe Bacchetta, and Abhijit Banerjee. 2000. Currency Crises and Mon- etary Policy with Credit Constraints. Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. Photocopy. Aghion, Philippe, Philippe Bacchetta, and Abhijit Banerjee. 2001. A Corporate Balance Sheet Approach to Currency Crises. Photocopy. www.hec.unil.ch/deep/textes/01.14.pdf. Alesina, Alberto, and Guido Tabellini. 1990. A Positive Theory of Fiscal Deficits and Gov- ernment Debt. Review of Economic Studies 57: 403–14. Allen, Franklin, and Douglas Gale. 2000a. Optimal Currency Crises. New York University. Photocopy (April). www.econ.nyu.edu/user/galed/occ.pdf. Allen, Franklin, and Douglas Gale. 2000b. Comparing Financial Systems. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Allen, Mark, Christoph Rosenberg, Christian Keller, Brad Setser, and Nouriel Roubini. 2002. A Balance Sheet Approach to Financial Crisis. IMF Working Paper 02/210 (December). Washington: International Monetary Fund. www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2002/ wp02210.pdf. Arbelaez, Maria Angelica, María Lucía Guerra, and Nouriel Roubini. Forthcoming. Debt Dy- namics and Debt Sustainability in Colombia. In Fiscal Reform in Colombia, ed. J. Poterba. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Banque de France. 2003. Toward a Code of Good Conduct on Sovereign Debt Renegotiation. Issues paper prepared by Banque de France staff. Paris: Banque de France. Bartholomew, Ed, Ernest Stern, and Angela Liuzzi. 2002. Two-Step Sovereign Debt Restruc- turing. New York: JP Morgan Chase and Co. www.emta.org/keyper/barthol.pdf. Becker, T., A. S. Richards, and T. Thaicharoen. 2003. Bond Restructuring and Moral Hazard: Are CACs Costly? Journal of International Economics 61: 127–61. -

China–Africa and an Economic Transformation OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/4/2019, Spi

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/4/2019, SPi China–Africa and an Economic Transformation OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/4/2019, SPi Praise for the book ‘This book’s accessible up-to-date assessment on the evolving trade and invest- ment relations between China and Africa is a welcome contribution to a field that is under-studied. The asymmetry in Africa-China relations is recognised and honestly addressed, including insights into governance arrangements. Lin and Oqubay’s book is academically rigorous, and also offers immensely practical guidance to Chinese and African stakeholders on how to build this partnership going forward.’ Dr Miriam Altman, PhD, Commissioner in the South African National Planning Commission ‘This is an extremely important volume. In the chatter on China and Africa, the Chinese and Africans are the very ones often left out. The editors them- selves represent a departure from “being spoken to” by a Western world with its own distinct interests. They have assembled a set of chapters of deep insights into collaboration in specific countries and which speak to a complex situation that indicates a changed world because of China and Africa.’ Stephen Chan OBE, Professor of World Politics, SOAS University of London ‘This book comes at a critical moment in China-Africa relations, as both sides explore ways to reach their partnership potential. The 2018 FOCAC Beijing Summit launched an ambitious cooperation agenda in support of Africa’s development, as encapsulated in Agenda 2063. We also agreed to advance shared priorities on -

The Korean Financial Crisis of 1997: Onset, Turnaround, and Thereafter, Which I Originally Authored in Korean in 2006

The Korean Financial Crisis of 1997 Onset, Turnaround, and Thereafter Public Disclosure Authorized Kyu-Sung LEE Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized The Korean Financial Crisis of 1997 The Korean Financial Crisis of 1997 ONSET, TURNAROUND, AND THEREAFTER Kyu-Sung LEE © 2011 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank and the Korea Development Institute 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org All rights reserved 1 2 3 4 14 13 12 11 The findings, interpretations, and conclusions herein are those of the author and do not reflect the views of the World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorse- ment or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA; telephone: 978-750-8400; fax: 978-750-4470; Internet: www.copyright.com. -

The Divergent International Response to China's Xinjiang's Policy

The Divergent International Response to China’s Xinjiang Policy Dorothy Settles HIST 402C: International Relations from the Asian Perspective Dr. Timothy Brook April 12, 2020 1 Introduction In response to ethnic and religious unrest in China’s northwestern province of Xinjiang, the Chinese Communist Party has engaged in a colossal crackdown on the local Uyghur Muslim population. In recent years, an estimated one million Uyghurs have been detained in re-education centers, which have been likened to concentration camps, while religious and cultural freedom has been forcibly suppressed1. This has generated a slew of strong yet divergent international reactions, ranging from outright support to passive silence to scathing condemnation. On July 8, 2019, a group of 22 predominantly Western countries issued a letter to the United Nations Human Rights Council condemning China for their oppression of the Uyghurs. Days later, 37 developing countries, many of which are Muslim-majority, came together and wrote a different letter to the UNHRC, “commend[ing] China’s remarkable achievements in the field of human rights,”2 in reference to their policies in Xinjiang. While it is initially shocking to see so many (especially Muslim) countries coming to China’s defense, it cannot be divorced from China’s burgeoning global influence. This paper analyzes the international response to China’s oppression of the Uyghurs, in order to understand the shifting face of the emerging Sino-centric world order. I argue that the emerging Sino-centric world order is becoming increasingly characterized by the dissolution of traditional transnational religious and cultural bonds and the emboldening of regimes that emphasize sovereignty over human rights. -

RBA Annual Report 2000

INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL CO-OPERATION international financial and Canada); and the IMF/World Bank, with co-operation around 180 members. The former was too The three years since the Asian crisis began narrow to carry out the necessary consultation have seen a substantial push within the and co-ordination among countries, while the international community for reform of the latter was too large to allow decisive actions to international financial system. The problems in deal with emerging problems. Asia (and in Eastern Europe and Latin America The initial response of the international as well) not only damaged the growth perform- community was to set up the G22, an ad hoc ance of the countries directly affected, but had group of 22 countries including those affected repercussions on major financial markets, and by the crisis. This group was able to make quick brought a recognition on the part of the progress on a number of issues, but the feeling international financial community that was that its membership was not balanced, changes should occur in the so-called inter- with some claiming that Asian countries (which national financial architecture. The RBA made up 10 of the 22) were over-represented. believed that it should contribute as strongly In the event, that group has been replaced as possible to this work, given the potential for by two new international groupings, which major changes to the shape of international seem to have a greater degree of permanance financial markets to emerge from the process. than the G22. The two groupings are the Financial As a result, the RBA increased significantly the Stability Forum and the G20. -

The G-20 and International Economic Cooperation: Background and Implications for Congress

The G-20 and International Economic Cooperation: Background and Implications for Congress Rebecca M. Nelson Analyst in International Trade and Finance August 10, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R40977 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress The G-20 and International Economic Cooperation Summary The G-20 is an international forum for discussing and coordinating economic policies. The members of the G-20 include Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, South Korea, Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States, and the European Union. Background: The G-20 was established in the wake of the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s to allow major advanced and emerging-market countries to coordinate economic policies. Until 2008, G-20 meetings were held at the finance minister level, and remained a less prominent forum than the G-7, which held meetings at the leader level (summits). With the onset of the global financial crisis, the G-7 leaders decided to convene the G-20 leaders to discuss and coordinate policy responses to the crisis. To date, the G-20 leaders have held four summits: November 2008 in Washington, DC; April 2009 in London; September 2009 in Pittsburgh; and June 2010 in Toronto. The G-20 leaders have agreed that the G-20 is now the premier forum for international economic coordination, effectively supplanting the G-7’s role as such. Commitments: Over the course of the four G-20 summits held to date, the G-20 leaders have made commitments on a variety of issue areas. -

Training Manual

IEA Training Manual A training manual on integrated environmental assessment and reporting Training Module 6 Scenario development and analysis Authors: Jill Jäger, The Sustainable Europe Research Institute (SERI) Dale Rothman, International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) Chris Anastasi, British Energy Group Sivan Kartha, Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI) Philip van Notten (Independent Scholar) Module 6 A training manual on integrated environmental assessment and reporting ii IEA Training Manual Scenario development and analysis Module 6 Table of Contents List of Acronyms iv Overview 1 Course Materials 3 1. Introduction and learning objectives 3 2. What is a scenario? 5 3. A very short history of scenario development 6 4. Examples of scenario exercises 7 4.1 Short-term country scenarios – Mont Fleur 7 4.2 Medium-term regional and global scenarios – The UNEP GEO-3 Scenarios 8 4.3 Long term global scenarios – Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 10 5. The purpose, process and substance of scenarios and scenario exercises 13 6. Policy analysis 16 7. Developing scenarios – A complete process 20 7.1 Clarifying the purpose and structure of the scenario exercise 22 7.2 Laying the foundation for the scenarios 28 7.3 Developing and testing the actual scenarios 33 7.4 Communication and outreach 36 References 38 Instructor Guidance and Training Plan 40 Presentation Materials 41 IEA Training Manual iii Module 6 A training manual on integrated environmental assessment and reporting List of Acronyms AIM Asia-Pacific Integrated -

Studia Diplomatica Lxviii-3 (2017) the Future of the Gx

stud.diplom.2017-3.book Page 1 Tuesday, May 30, 2017 9:26 AM STUDIA DIPLOMATICA LXVIII-3 (2017) THE FUTURE OF THE GX SYSTEM AND GLOBAL GOVERNANCE Edited by Peter DEBAERE, Dries LESAGE & Jan WOUTERS Royal Institute for International Relations stud.diplom.2017-3.book Page 2 Tuesday, May 30, 2017 9:26 AM Studia Diplomatica – The Brussels Journal of International Relations has been published since 1948 by Egmont – Royal Institute for International Relations. President: Viscount Etienne DAVIGNON Director-General: Marc OTTE Editor in Chief: Prof. Dr. Sven BISCOP Egmont – The Royal Institute for International Relations Address FPS Foreign Affairs, Rue des Petits Carmes 15, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Phone +32-(0)2.223.41.14 Fax +32-(0)2.223.41.16 E-mail [email protected] Website www.egmontinstitute.be Subscription: € 85 (Belgium) € 100 (Europe) € 130 (worldwide) Lay-out: punctilio.be Cover: Kris Demey ISSN: 0770-2965 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publishers. stud.diplom.2017-3.book Page 1 Tuesday, May 30, 2017 9:26 AM Table of Contents 3 The Future of the Gx System and Global Governance: An Introduction Peter Debaere, Dries Lesage & Jan Wouters 7 Governing Together: The Gx Future John Kirton 29 Russia and the Future of the Gx system Victoria V. Panova 45 The Gx Contribution to Multilateral Governance: Balancing Efficiency and