Abstract a Feminist Interpretation of Korean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animals and Morality Tales in Hayashi Razan's Kaidan Zensho

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses March 2015 The Unnatural World: Animals and Morality Tales in Hayashi Razan's Kaidan Zensho Eric Fischbach University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2 Part of the Chinese Studies Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Translation Studies Commons Recommended Citation Fischbach, Eric, "The Unnatural World: Animals and Morality Tales in Hayashi Razan's Kaidan Zensho" (2015). Masters Theses. 146. https://doi.org/10.7275/6499369 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/146 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNNATURAL WORLD: ANIMALS AND MORALITY TALES IN HAYASHI RAZAN’S KAIDAN ZENSHO A Thesis Presented by ERIC D. FISCHBACH Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS February 2015 Asian Languages and Literatures - Japanese © Copyright by Eric D. Fischbach 2015 All Rights Reserved THE UNNATURAL WORLD: ANIMALS AND MORALITY TALES IN HAYASHI RAZAN’S KAIDAN ZENSHO A Thesis Presented by ERIC D. FISCHBACH Approved as to style and content by: __________________________________________ Amanda C. Seaman, Chair __________________________________________ Stephen Miller, Member ________________________________________ Stephen Miller, Program Head Asian Languages and Literatures ________________________________________ William Moebius, Department Head Languages, Literatures, and Cultures ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank all my professors that helped me grow during my tenure as a graduate student here at UMass. -

Santa Fe New Mexican, 06-07-1913 New Mexican Printing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 6-7-1913 Santa Fe New Mexican, 06-07-1913 New Mexican Printing company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news Recommended Citation New Mexican Printing company. "Santa Fe New Mexican, 06-07-1913." (1913). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news/3818 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 ! SANTA 2LWWJlaWl V W SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO, SATURDAY, JUNE 7, 191J. JVO. 95 WOULD INVOLVE PRESIDlNT D0RMAN THE SQUEALERS. CONFERENCE OF ! SENDS GREETINGS GOVERNORS THE CHAMBER OF COMMERCE HAS A COMPREHENSIVE FOLDER PRIN- WILSON TED SEND TO THE BROTHERHOOD CLOSES OF AMERICAN YEOMEN, CALLING REPUBLICAN SENATORS STILL INS-SIS- T ATTENTION TO SANTA FE S WILL DRAFT ADDRESS TO PUBLIC THAT PRESIDENT IS USING LAND OFFICE COMMISSIONER MORE INFLUENCE FOR TARIFF TALLMAN AND A. A. JONES PRO-- i If the smoker and lunch given by THAN ANYONE ELSE. MISE HELP OF THE the chamber of commerce brought forth nothing else, the issuing of WILSON IS LOBBYING greetings to the supreme conclave of the Brotherhood of American Yeoman, FOR THE PEOPLE Betting forth some of the facts re- PROSPECTORS WILL garding Santa Fe and its remarkable climate was worth accomplishment. BE ENCOURAGED Washington, D. C, June 7. -

Financial Statements Summary

3Q 2019 Earnings Release Studio Dragon November 7, 2019 Disclaimer This financial information in this document are consolidated earnings results based on K-IFRS. This document is provided for the convenience of investors only, before the external audit on our 3Q 2019 financial results is completed. The audit outcomes may cause some parts of this document to change. In addition, this document contains “forward-looking statements” – that is, statements related to future, not past, events. In this context, “forward-looking statements” often address our expected future business and financial performance, and often contain words such as “expects”, “anticipates”, “intends”, “plans”, “believes”, “seeks” or “will”. Our actual results to be materially different from those expressed in this document due to uncertainties. 3Q 2019 Earnings Release TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 3Q 2019 Highlights 2 3Q 2019 Operating Performance º Programing º Distribution º Cost 3 Growth Strategies Appendix We Create New Culture 1 3Q 2019 Highlights <Arthdal Chronicles> <Hotel Del Luna> <Miss Lee> <Watcher> <Mr. Temporary> <The Running Mates> <Love Alarm> (1) Programming Distribution Production Revenue Revenue Revenue Trend W131.2bn w60.8bn w60.0bn 13titles (YoY +6.0%) (YoY +24.4%) (YoY -5.4%) (YoY +5 titles) Note (1) Each quarter includes all titles in progress - 4 - We Create New Culture 12 3Q 2019 Operating Performance Summary 3Q19 Revenue (+6.0% YoY) – Hit a record high, driven by diversified business, premium IP, and expanded lineups OP (-49.2% YoY) – Maintained stable fundamentals amid last year’s high-base <Mr. Sunshine> and BEP of <Arthdal Chronices> 4Q19 Aim to reinforce influence via titles incl. -

Studio Dragon (253450) Update Fundamental S to Improve in 2020

2019. 10. 31 Company Studio Dragon (253450) Update Fundamental s to improve in 2020 ● The business environment in Korea and overseas is moving favorably for the Minha Choi media industry—eg , OTT platforms are launching around the world, a number of Analyst Korean players are engaging in M&A activity, and terrestrial broadcasters are [email protected] investing more heavily in tent-pole content. These developments should lead to 822 2020 7798 more demand for quality content, which bodes well for content producers in 2020. Kwak Hoin ● Studio Dragon should enjoy greater earnings stability by producing multi-season Research Associate original content for OTT services. It may produce content for both Netflix and new [email protected] global players. Terrestrial broadcasters are also eager to secure quality content. 822 2020 7763 ● Capitalizing on its popular intellectual property and production prowess, the firm has been expanding into new business areas and should see solid top- and bottom-line growth next year. We raise our 12-month target price to KRW88,000. WHAT’S THE STORY? Poised to benefit from sea change in media market: The business environment has been changing quickly at home and abroad. Several global giants are preparing to launch OTT platforms from November, and, in response, Korean OTT service providers are teaming up to boost their competitiveness. Struggling from low viewership ratings, the country’s three terrestrial broadcasters have altered programming lineups and in AT A GLANCE September launched OTT platform Wavve in partnership with SK Telecom—the latter a move that may lead to greater investment in tent-pole dramas. -

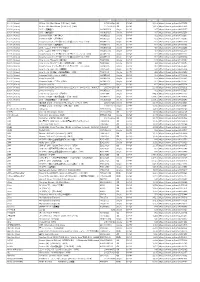

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 100% (Korea) How to cry (ミヌ盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5005 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415958 100% (Korea) How to cry (ロクヒョン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5006 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415970 100% (Korea) How to cry (ジョンファン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5007 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415972 100% (Korea) How to cry (チャンヨン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5008 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415974 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you (A) OKCK5011 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655024 100% (Korea) Song for you (B) OKCK5012 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655026 100% (Korea) Song for you (C) OKCK5013 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655027 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) -

Big Bang – Shout out to the World!

Big Bang – Shout Out To The World! (English Translation) [2009] Shout out to the World: TOP “I came here because of that string of hope. Where do I stand now? I ask myself this but even I don’t have a specific answer yet. During the process where I search for my other self, all my worries will fade away because I must find the person who will lend his shoulders to me.” ~TOP Name: Choi Seung-hyun Date of Birth: November 4, 1987 Skills: Rap, Writing lyrics, Beatbox *Starred in the KBS Drama, ‘I am Sam’ The power to awaken a soul, sometimes it takes pain to be re-born. [~ Pt.One~] -I once wanted to be a lyric poet that composed and recited verses.- I became mesmerized with ‘Hip-Hop’ music when I was in Grade 5. I went crazy for this type of music because I listened to it all day and carefully noted all the rap lyrics. If we have to talk about Hip-Hop music, I have to briefly talk about the roots of American Hip-Hop. When I first started listening to Hip-Hop, it was divided up into East Coast and West Coast in America. Wu Tang Clan and Notorius B.I.G. represented the East Coast (New York) scene and they focused largely on the rap and the lyrics, while representing the West Coast (LA) was 2Pac who focused more on the melody. Although at that time in Korea and from my memory, more people listened to West Coast hip hop but I was more into the East Coast style. -

Nchor Newspapers

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC The Anchor Newspapers 12-9-1954 The Anchor (1954, Volume 27 Issue 04) Rhode Island College of Education Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/the_anchor Recommended Citation Rhode Island College of Education, "The Anchor (1954, Volume 27 Issue 04)" (1954). The Anchor. 185. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/the_anchor/185 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Anchor by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NCHOR Vol. XXVII, No.~,.;;:==;._.--- RHODE ISLAND COLLEGE OF EDUCATION December 9, 1954 1 PROFESSORSFLASH THERE IS A NEED CHANGE! by Louise Hass an TAKE LEAVE Word has been received from Rhode Island College of Education has made vast progress during During the next semester we the editors of Who's Who Among STUNT NIGHT the hundred years of its existence. The College was once a mere idea Students in American Universities in the minds of educators. During a forty year period these men and shall be missing some of the fam- will be held women struggled to make a dream a reality. A Normal Department iliar faces of our faculty. Prof. and Colleges that eight students Frank E. Greene and Dr. Helen January 14, 1955 was established at Brown University in 1850. Funds were appropriated have been accepted to represent appro E. Scott intend to spend the semes for a Normal School in Providence in 1854. In 1857 when the the College of Education in the Henry Barnard Auditorium ter in study. -

K-Pop in Latin America: Transcultural Fandom and Digital Mediation

International Journal of Communication 11(2017), 2250–2269 1932–8036/20170005 K-Pop in Latin America: Transcultural Fandom and Digital Mediation BENJAMIN HAN Concordia University Wisconsin, USA This article examines the transnational popularity of K-pop in Latin America. It argues K- pop as a subculture that transforms into transcultural fandom via digital mediation, further resulting in its accommodation into Latin American mass culture. The article further engages in a critical analysis of K-pop fan activism in Latin America to explore the transcultural dynamics of K-pop fandom. In doing so, the article provides a more holistic approach to the study of the Korean Wave in Latin America within the different “scapes” of globalization. Keywords: K-pop, fandom, Latin America, digital culture, Korean Wave The popularity of K-pop around the globe has garnered mass media publicity as Psy’s “Gangnam Style” reached number two on the Billboard Charts and became the most watched video on YouTube in 2012. Although newspapers, trade journals, and scholars have examined the growing transnational popularity of K-pop in East Asia, the reception and consumption of K-pop in Latin America have begun to receive serious scholarly consideration only in the last few years. Numerous reasons have been explicated for the international appeal and success of K-pop, but it also is important to understand that the transnational and transcultural fandom of K-pop cannot be confined solely to its metavisual aesthetics that creatively syncretize various genres of global popular music such as Black soul and J-pop. K-pop as hybrid music accentuated with powerful choreography is a form of visual spectacle but also promotes a particular kind of lifestyle represented by everyday modernity in which social mobility in the form of stardom becomes an important facet of the modernization process in Latin America. -

Introduction to Bengali, Part I

R E F O R T R E S U M E S ED 012 811 48 AA 000 171 INTRODUCTION TO BENGALI, PART I. BY- DIMOCK, EDWARD, JR. AND OTHERS CHICAGO UNIV., ILL., SOUTH ASIALANG. AND AREA CTR REPORT NUMBER NDEA.--VI--153 PUB DATE 64 EDRS PRICE MF -$1.50 HC$16.04 401P. DESCRIPTORS-- *BENGALI, GRAMMAR, PHONOLOGY, *LANGUAGE INSTRUCTION, FHONOTAPE RECORDINGS, *PATTERN DRILLS (LANGUAGE), *LANGUAGE AIDS, *SPEECHINSTRUCTION, THE MATERIALS FOR A BASIC COURSE IN SPOKENBENGALI PRESENTED IN THIS BOOK WERE PREPARED BYREVISION OF AN EARLIER WORK DATED 1959. THE REVISIONWAS BASED ON EXPERIENCE GAINED FROM 2 YEARS OF CLASSROOMWORK WITH THE INITIAL COURSE MATERIALS AND ON ADVICE AND COMMENTS RECEIVEDFROM THOSE TO WHOM THE FIRST DRAFT WAS SENT FOR CRITICISM.THE AUTHORS OF THIS COURSE ACKNOWLEDGE THE BENEFITS THIS REVISIONHAS GAINED FROM ANOTHER COURSE, "SPOKEN BENGALI,"ALSO WRITTEN IN 1959, BY FERGUSON AND SATTERWAITE, BUT THEY POINTOUT THAT THE EMPHASIS OF THE OTHER COURSE IS DIFFERENTFROM THAT OF THE "INTRODUCTION TO BENGALI." FOR THIS COURSE, CONVERSATIONAND DRILLS ARE ORIENTED MORE TOWARDCULTURAL CONCEPTS THAN TOWARD PRACTICAL SITUATIONS. THIS APPROACHAIMS AT A COMPROMISE BETWEEN PURELY STRUCTURAL AND PURELYCULTURAL ORIENTATION. TAPE RECORDINGS HAVE BEEN PREPAREDOF THE MATERIALS IN THIS BOOK WITH THE EXCEPTION OF THEEXPLANATORY SECTIONS AND TRANSLATION DRILLS. THIS BOOK HAS BEEN PLANNEDTO BE USED IN CONJUNCTION WITH THOSE RECORDINGS.EARLY LESSONS PLACE MUCH STRESS ON INTONATION WHIM: MUST BEHEARD TO BE UNDERSTOOD. PATTERN DRILLS OF ENGLISH TO BENGALIARE GIVEN IN THE TEXT, BUT BENGALI TO ENGLISH DRILLS WERE LEFTTO THE CLASSROOM INSTRUCTOR TO PREPARE. SUCH DRILLS WERE INCLUDED,HOWEVER, ON THE TAPES. -

This Is a Reproduction of a Library Book That Was Digitized by Google As

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com §§§ §9 #y 30 THIRTIETH Rºſſ EDITION.—ENLARGED. ºf A . A n e w a N D co at tº L. E. T. E. Hº Y MIN A N }} } {} N ý B {} {} {{. ro R. S A B B A T H S G H 0 0 H, S. B. r WILLIAM B. B R A D BURY, arraoa or *rum saawº,” “run uusilan," "sixdino stan,” “sannaru somool cuoin,” sº. C IN C IN N AT I: MOORE, WIL STA C H & B A LDWIN, 25 west Fou R T H st R E ET, 1864 Enturad according to Act of Congn«, In the year 185U, lnd sgain In 1s82, 07 fi WILLIAM B. BRADBURY, In ths Clerk's Offloe of the District Court for the District of New Jersey. с. PREFACE NEXT to a good Superintendent, that which tends not in any peculiar tense children's tones, and the more than any thing else to make a Sunday School children should not be limited tn them. popular, is, doubtless, GOOD SIMCIKS. And this should The popular tunes for children should be as simple generally ho characterized by sprightlmesg and cheer- as their own thoughts, — sprightly as their own die- ftili IOP-S, tempered with gentleness. " Animated, but positions. Lambs require plenty of skipping room. not hoisterous; gentle, but not dull or tame," are direc They thrive best in the green fields. -

URL 100% (Korea)

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤C> OKCK5022 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732096 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤B> OKCK5021 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732095 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (チャンヨン)(LTD) OKCK5017 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655033 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤A> OKCK5020 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732093 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ジョンファン)(LTD) OKCK5016 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655032 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ヒョクジン)(LTD) OKCK5018 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655034 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 Single K-POP 421 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 -

Seiko's Story Seiko's Life 1.6 Seiko and Mike ©Seiko&Mike LLC 2020 1

Seiko’s Story Seiko’s Life 1.6 Seiko and Mike They Move in Together • Seiko and Mike Meet, Christmas, 1967 • First Date, Part 1, Open Restaurant, Mid-Jan, 1968 • First Date, Part 2, Private Café, Mid-Jan, 1968 • Mike is Very Interested and Wants to Know More About Seiko • Second Date, and“Marry Me” Mid-Feb, 1968 • 2nd Date. What Just Happened? • 2nd Date, What Just Happened, 45 Years Later, Continued • Mike Meets Seiko’s Family • Seiko and Mike Move into A House in Fussa (Apr 1968) ©Seiko&Mike LLC 2020 1 Seiko’s Story Seiko’s Life 1.6 Seiko and Mike Seiko and Mike Meet, Christmas, 1967 Prologue Mike’s roommate, Alton, at Yokota Air Force Base, was dating Mieko and had a group photo on top of his dresser. Mike asked about the picture, and Alton told Mike it was the Meiji Shrine Client escorts, and Mieko, his girlfriend, was one of them. All of the girls but one were wearing grey pinstripe uniforms. Alton pointed out Mieko to Mike. One girl, however, was wearing a flowing white skirt and white sweater. Mike asked about the girl in the center in white. Alton said that that was Seiko. He said Seiko and Seiko 1968, 23 years old Mieko were good friends, and Seiko was the manager of the girls. Mike told Alton, “I would like to meet Seiko.” Alton got Mieko to arrange for Mike and Alton to meet the girls at Seiko’s house on an evening in late December 1967. They were delayed and did not get to Seiko’s house until about 9:45.