Section a Concept and Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANDERTON Music Festival Capitalism

1 Music Festival Capitalism Chris Anderton Abstract: This chapter adds to a growing subfield of music festival studies by examining the business practices and cultures of the commercial outdoor sector, with a particular focus on rock, pop and dance music events. The events of this sector require substantial financial and other capital in order to be staged and achieve success, yet the market is highly volatile, with relatively few festivals managing to attain longevity. It is argued that these events must balance their commercial needs with the socio-cultural expectations of their audiences for hedonistic, carnivalesque experiences that draw on countercultural understanding of festival culture (the countercultural carnivalesque). This balancing act has come into increased focus as corporate promoters, brand sponsors and venture capitalists have sought to dominate the market in the neoliberal era of late capitalism. The chapter examines the riskiness and volatility of the sector before examining contemporary economic strategies for risk management and audience development, and critiques of these corporatizing and mainstreaming processes. Keywords: music festival; carnivalesque; counterculture; risk management; cool capitalism A popular music festival may be defined as a live event consisting of multiple musical performances, held over one or more days (Shuker, 2017, 131), though the connotations of 2 the word “festival” extend much further than this, as I will discuss below. For the purposes of this chapter, “popular music” is conceived as music that is produced by contemporary artists, has commercial appeal, and does not rely on public subsidies to exist, hence typically ranges from rock and pop through to rap and electronic dance music, but excludes most classical music and opera (Connolly and Krueger 2006, 667). -

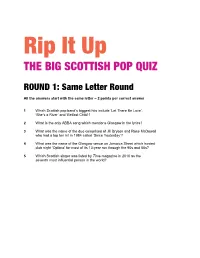

Big Scottish Pop Quiz Questions

Rip It Up THE BIG SCOTTISH POP QUIZ ROUND 1: Same Letter Round All the answers start with the same letter – 2 points per correct answer 1 Which Scottish pop band’s biggest hits include ‘Let There Be Love’, ‘She’s a River’ and ‘Belfast Child’? 2 What is the only ABBA song which mentions Glasgow in the lyrics? 3 What was the name of the duo comprised of Jill Bryson and Rose McDowall who had a top ten hit in 1984 called ‘Since Yesterday’? 4 What was the name of the Glasgow venue on Jamaica Street which hosted club night ‘Optimo’ for most of its 13-year run through the 90s and 00s? 5 Which Scottish singer was listed by Time magazine in 2010 as the seventh most influential person in the world? ROUND 1: ANSWERS 1 Simple Minds 2 Super Trouper (1st line of 1st verse is “I was sick and tired of everything/ When I called you last night from Glasgow”) 3 Strawberry Switchblade 4 Sub Club (address is 22 Jamaica Street. After the fire in 1999, Optimo was temporarily based at Planet Peach and, for a while, Mas) 5 Susan Boyle (She was ranked 14 places above Barack Obama!) ROUND 6: Double or Bust 4 points per correct answer, but if you get one wrong, you get zero points for the round! 1 Which Scottish New Town was the birthplace of Indie band The Jesus and Mary Chain? a) East Kilbride b) Glenrothes c) Livingston 2 When Runrig singer Donnie Munro left the band to stand for Parliament in the late 1990s, what political party did he represent? a) Labour b) Liberal Democrat c) SNP 3 During which month of the year did T in the Park music festival usually take -

Celebrating 20 Years As the T in T in the Park: Tennent's

CELEBRATING 20 YEARS AS THE T IN T IN THE PARK: TENNENT’S LAGER’S JOURNEY AS FOUNDING PARTNER OF SCOTLAND’S BIGGEST FESTIVAL Marketing Society Scotland Star Awards 2014 Category 3.7: PR Tennent’s Lager - T in the Park 2013 Material_UK PRECIS In 2013, T in the Park celebrated 20 years as Scotland’s biggest festival, and Scotland’s favourite pint Tennent’s Lager celebrated 20 years as its founding partner. The milestone represented a major PR opportunity to tell the story of Tennent’s’ 20-year journey as the T in T in the Park, and revitalise the sponsorship’s relevance to its target market by positioning the brand at the heart of the festivities. A creative and high profile campaign generated a nationwide buzz for the 20th year of T in the Park, successfully engaging consumers and media in the celebrations and delivering strong AVE and brand cut- through. Marketing Society Scotland Star Awards 2014 Category 3.7: PR Tennent’s Lager - T in the Park 2013 Material_UK BACKGROUND – A 20 YEAR JOURNEY Over the past two decades, Tennent’s Lager has cultivated a strong emotional connection with over 2.5million festival-goers through its iconic and ground-breaking title sponsorship of T in the Park (TITP). The brand has been at the heart of the TITP experience for generations of music fans since the festival’s inception in 1994, which has enabled it to build brand relevance within its target market and develop an increased share of their lager consumption. More than just a sponsor, Tennent’s are cofounders of the festival, and together with the country’s leading live music promoter DF Concerts, they have shaped its evolution into a landmark event on Scotland’s cultural landscape, one which attracts a daily crowd of 85,000 music fans as well as the biggest artists in the world to Balado every July. -

From Glyndebourne to Glastonbury: the Impact of British Music Festivals

An Arts and Humanities Research Council- funded literature review FROM GLYNDEBOURNE TO GLASTONBURY: THE IMPACT OF BRITISH MUSIC FESTIVALS Emma Webster and George McKay 1 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE 4 INTRODUCTION 6 THE IMPACT OF FESTIVALS: A SURVEY OF THE FIELD(S) 7 ECONOMY AND CHARITY SUMMARY 8 POLITICS AND POWER 10 TEMPORALITY AND TRANSFORMATION Festivals are at the heart of British music and at the heart 12 CREATIVITY: MUSIC of the British music industry. They form an essential part of AND MUSICIANS the worlds of rock, classical, folk and jazz, forming regularly 14 PLACE-MAKING AND TOURISM occurring pivot points around which musicians, audiences, 16 MEDIATION AND DISCOURSE and festival organisers plan their lives. 18 HEALTH AND WELL-BEING 19 ENVIRONMENT: Funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, the LOCAL AND GLOBAL purpose of this report is to chart and critically examine 20 THE IMPACT OF ACADEMIC available writing about the impact of British music festivals, RESEARCH ON MUSIC drawing on both academic and ‘grey’/cultural policy FESTIVALS literature in the field. The review presents research findings 21 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR under the headings of: FUTURE RESEARCH 22 APPENDIX 1. NOTE ON • economy and charity; METHODOLOGY • politics and power; 23 APPENDIX 2. ECONOMIC • temporality and transformation; IMPACT ASSESSMENTS • creativity: music and musicians; 26 APPENDIX 3. TABLE OF ECONOMIC IMPACT OF • place-making and tourism; MUSIC FESTIVALS BY UK • mediation and discourse; REGION IN 2014 • health and well-being; and 27 BIBLIOGRAPHY • environment: local and global. 31 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It concludes with observations on the impact of academic research on festivals as well as a set of recommendations for future research. -

3.5 Event Marketing Precis

CAMPAIGN: #HELLOSTRATHALLAN - T IN THE PARK 2016 AGENCY: DF CONCERTS & MATERIAL_UK CATEGORY: 3.5 EVENT MARKETING PRECIS T in the Park (TITP) is one of Europe’s leading festivals – a cornerstone of Scottish culture and a rite of passage for music fans across the country. Co-founded in 1994 by DF Concerts and Tennent’s Lager, over the past 22 years the festival has grown in influence and reputation and is now a major player on the world stage. THE CHALLENGES In 2015, T in the Park faced the biggest challenge of its 22-year history, with the festival relocating from its much-loved Balado home to a brand new site – Strathallan Castle. The complexities involved with moving Scotland’s biggest music event were not to be underestimated, and neither was the level of media attention this would inevitably generate. Understandably festival-goers were apprehensive – how would the new site compare to their beloved Balado? This fell at a time when T in the Park faced increasing competition from the wider UK and European festival market. It was imperative that T in the Park upheld its reputation as an unmissable festival experience. AMBITIONAMBITION ANDAND OBJECTIVESOBJECTIVES TARGET MARKET We knew our marketing and communications strategy had to be confident, savvy and engaging for our target market, which comprised: • Primary target market - music fans in Scotland (core demographic: 18-24 year-olds) • Secondary target market: music fans outwith Scotland - across the UK and Europe CAMPAIGN OBJECTIVES • Capitalise on the PR and marketing opportunities presented by the new site move • Reinforce TITP’s stature as an internationally acclaimed festival and a major event on the global stage • Create a high ATL and media profile for the event to drive ticket sales and consumer engagement • Drive sales of key revenue generation initiatives and services ie. -

Detecting Disease Outbreaks in Mass Gatherings Using Internet Data

JOURNAL OF MEDICAL INTERNET RESEARCH Yom-Tov et al Original Paper Detecting Disease Outbreaks in Mass Gatherings Using Internet Data Elad Yom-Tov1, BSc, MA, PhD; Diana Borsa2, BSc, BMath, MSc (Hons); Ingemar J Cox3,4, BSc, DPhil; Rachel A McKendry5, BSc, PhD 1Microsoft Research Israel, Herzelia, Israel 2Centre of Computational Statistics and Machine Learning (CSML), Department of Computer Science, University College London, University of London, London, United Kingdom 3Copenhagen University, Department of Computer Science, Copenhagen, Denmark 4University College London, University of London, Department of Computer Science, London, United Kingdom 5University College London, University of London, London Centre for Nanotechnology and Division of Medicine, London, United Kingdom Corresponding Author: Diana Borsa, BSc, BMath, MSc (Hons) Centre of Computational Statistics and Machine Learning (CSML) Department of Computer Science University College London, University of London Malet Place Gower St London, WC1E 6BT United Kingdom Phone: 44 20 7679 Fax: 44 20 7387 1397 Email: [email protected] Abstract Background: Mass gatherings, such as music festivals and religious events, pose a health care challenge because of the risk of transmission of communicable diseases. This is exacerbated by the fact that participants disperse soon after the gathering, potentially spreading disease within their communities. The dispersion of participants also poses a challenge for traditional surveillance methods. The ubiquitous use of the Internet may enable the detection of disease outbreaks through analysis of data generated by users during events and shortly thereafter. Objective: The intent of the study was to develop algorithms that can alert to possible outbreaks of communicable diseases from Internet data, specifically Twitter and search engine queries. -

The Best of MTV England & Scotland

04_587733 ch01.qxp 4/23/07 11:04 AM Page 1 The Best of MTV England & Scotland The Best Brit Travel Experiences DFish and Chips: Don’t eat them in a Cambridge. And don’t forget the cucumber restaurant. These need to be smothered in sandwiches and chilled champers. salt, vinegar, and tomato ketchup, wrapped DA Night out Clubbing: Take your pick in paper, and eaten outside. Think wind- of the cities—London, Leeds, Newcastle, blown beach after you’ve just finished Manchester, Brighton, Glasgow. The Super- surfing, or park bench after a night out. club may have died a death, but even hip- DWeekend at a British Music Festival: per clubs have sprung up in its place and It doesn’t matter which one you’re at— the UK still has some of the world’s top DJs. Glastonbury, Reading, T in the Park—it will DPub Crawl: Forget barhopping, it’s so rain, the toilets will overflow, you will lose sterile. Instead, have yourself an English all your friends, and you will have the time pub crawl, stumbling from places like The of your life. Guaranteed. Royal Oak to the Old House at Home, chat- DWalk in the Rain: It’s going to rain at ting to the locals, getting the rounds in, some point in your trip, so why not savor downing pints, eating pork scratchings, the experience? Bundle up, head up onto a playing pool, and flirting with the bar staff. wild moor or cliff top, and let the wind and What could be more British? rain blast at your cheeks until they’re the DReal Ale by a Log Fire: Bottled color of freshly picked radishes. -

Market Report 2018 Meet the Festival-Goers

MARKET REPORT 2018 MEET THE FESTIVAL-GOERS... AGE 2% under 16 5% 16-17 41% 12% 18-20 of festival goers attend 13% 21-25 10% 26-30 6-20 gigs per year 7% 31-34 11% 25-40 GENDER 19% 41-50 56% 14% 51-60 44% 6% 60+ WHEN THEY BOUGHT TICKETS SCOTLAND 3% ABROAD 16% NORTHERN IRELAND 2% When early bird tickets went on-sale - 45% North East 8% When general release tickets went on-sale - 19% North West 14% When my friends bought theirs - 32% REPUBLIC OF IRELAND 1% After the headliners were announced - 32% Midlands 10% When the full line-up had been released - 23% WALES 3% EAST ANGLIA 4% After I saw it advertised - 16% LONDON 7% When there was an early-bird offer - 14% SOUTH WEST 12% SOUTH EAST 16% After I saw it featured in print or online media - 5% After someone I trusted recommended it to me - 11% After I saw it promoted on social media - 13% After a new music release of an artist performing - 4% WHERE THEY LIVE When non-music entertainment was announced - 1% Other (please specify) - 5% Pop / RnB FESTIVAL TICKET PRICES... Hip hop / Grime Good value for MONEY 20% Rock / Indie What type of music They’re about do they like? Dance RIGHT 55% other Classical Overpriced for Ambient / what they deliver Electronica 25% World / Reggae Metal / Punk Jazz / Funk / Soul / Blues Folk / Country THEY BOUGHT THEIR FESTIVAL TICKETS... 45% When early bird tickets went on-sale HOW MANY GIGS DO THEY ATTEND PER YEAR? HOW MANY FESTIVALS DID THEY ATTEND THIS YEAR? 32% When friends bought theirs 1-2 16% None 18% One 32% 32% 3-5 30% After the headliners had Two 25% been -

Exploring the UK Festival Scene

Exploring the UK Festival scene What makes a festival? Or more specifi - and ingrained in the festival spirit. traditional ‘fallow year’, while the whimsi - cally, what makes a British festival? Across While Glastonbury is largely recognised cally eclectic Secret Garden Party, a won - fields, seafronts and the paved streets of now as being the pinnacle of the festival derland of neon and glitter in the London, summer brings people of all in - scene, the Isle of Wight was at the fore - Cambridge village of Abbots Ripton, per - terests and backgrounds together as one. front. Beginning as a counterculture event manently came to an end last year and In 1971, a year after its debut, a film between 1968 and 1970, it was recognised Scotland’s T in the Park has announced a crew captured the atmosphere of as the British equivalent of Woodstock. Its hiatus. ese aside, though, leaves no Glastonbury festival (see Nicolas Roeg’s 1970 line-up consisted of Joni Mitchell shortage especially as T in the Park has documentary Glastonbury Fayre ). Hair standing harmoniously in a yellow maxi been replaced by TRNSMT, a city festival flowed, tan coloured flares danced, tassels dress under the afternoon sun and Leonard in the centre of Glasgow which happens waved and light-weight, loose garments Cohen gripping the audience with his over the last weekend of June and first seemingly floated with the bodies of their tuneful poetry. e Who and e Doors weekend of July. supplied the rock and roll while Jimi wearers moving in swirling hypnotic mo - While most festivals are a temporary tions to the banging of drums. -

Window on Britain

WINDOW ON BRITAIN NAME: _____________________________ 3 ESO ____ YEAR 2018-2019 INS JULIO ANTONIO Let me introduce myself Hi, my name’s .................. I’m from .................. (country) I live in .................. (city) My birthday is on .................. There are ... people in my family. Hobbies – Free time activities reading, painting, drawing They are ............................................... going out with friends My father is a ............... and my mother a .................. surfing the Internet clubbing, barhopping My hobby is ....................... going to the cinema playing with my dog My favourite sport is ....................... going to the park/beach/… listening to music In my free time, I also like .............................. shopping, singing, dancing I don’t like .............................. travelling, camping, hiking knitting, cooking My favourite food is ....................... My favourite drink is ....................... Favourite places My favourite day of the week is ............ because ..................... my home my living room My favourite month is ................. because ...................... my bedroom the beach My favourite singer (or band) is ................. the shopping mall the sports centre I like ................. (movies). the library the park My favourite place is .................. I like it because ................. (…) I (don’t) like travelling. I have been to .................. Movies The most beautiful place in my country is .................. action movie comedy I study English because ................................. romantic comedy horror movie sci-fi movie war movie thriller Because… animated cartoons … I like it a lot. … I think it’s important. … I need to use it for work. Jobs … there are many things to see and do. teacher policeman doctor … I have to. nurse builder architect … I can relax there. civil servant engineer social worker … it’s relaxing/popular/nice/… secretary businessman shop assistant … it’s the last day of the week. -

Music Finland UK

Music Finland UK 2012–2013 / REPORT “It seems to me that at the moment “It takes a lot to get noticed in a place “Through The Line of Best Fit’s continued like London where there is so much going on all obsession with Nordic music and our historical Finland has an awful lot to offer in music. the time. But I think with the LIFEM – The Finnish links with the likes of the Ja Ja Ja club night in Line concerts at Kings Place, the Ja Ja Ja London, we’ve always kept a very close eye on And it’s about time we need to go and find it, Festival at the Roundhouse and the Songlines the sounds coming out of Finland. In the last CD, Finnish music really did make an impact. It’s three years, the quality of emerging talent has explore it, share it with people – because it’s the quirky, surprising and adventurous quality been just incredible and we’re seeing some real- of Finnish music that stands out – alongside ly unique invention and envelope–pushing from just too good to hide!” the musical virtuosity.“ all of the bands on this special release.” SIMON BROUGHTON / SONGLINES PAUL BRIDGEWATER / THE LINE OF BEST FIT, JOHN KENNEDY / XFM COMMENTING ON THE LINE–UP FOR MUSIC FINLAND’S OFFICIAL RECORD STORE DAY RELEASE 2013 “While Finland in the past might have “One of the best musical experiences held back a little from taking its scene to the of 2013 for me was going to Helsinki’s Kuudes world, their current united front means this is Aisti festival – an amazing site and brilliant “Having recently attended festivals in “Finland’s musical life is still a shining example changing. -

Waste Management at Outdoor Events

Julie’s Bicycle Practical Guide: Waste Management at Outdoor Events The arts and creative industries are ideally placed to lead on environmental sustainability; with creativity and inspiration they can champion a greener economy, energy efficiency, challenge our reliance on fossil fuels, make creative use of otherwise wasted materials and open new ways to greener production and living. Waste at Outdoor Events: Version 2014 Julie’s Bicycle Practical Guide: Waste Management at Outdoor Events V12 2015 1 Julie’s Bicycle Practical Guide: Waste Management at Outdoor Events © Julie's Bicycle 2015 Julie’s Bicycle Creating the Conditions for Change There are four key stages to taking action on environmental sustainability: Practical Guide: it mm U Waste Management at Outdoor Events o nd C e r s t a n d e t a c i n u I m m m p o r o C v e • Commit: put in place the structures, resources, policies Your success at integrating environmental sustainability into What this guide will cover Who is this guide for? What this guide will not cover and responsibilities necessary to support and action the way you work is often dependant on the internal culture your initiatives. of your organisation and the resources available to you. This guide will help organisers This guide is aimed at anyone involved This guide focuses on waste of outdoor events develop an in waste management decision making management in the context of • Understand: understand your impacts and establish Your key ingredients are: knowledge; skills; time and environmentally sustainable approach at events, particularly event managers, environmental sustainability and is systems to measure and monitor them on a continuous enthusiastic people.