B-09-303-11/2013 Between Nik Nazmi Bin Nik

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Khamis, 10 Disember 2020 Mesyuarat Dimulakan Pada Pukul 10.00 Pagi DOA [Tuan Yang Di-Pertua Mempengerusikan Mesyuarat]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9684/khamis-10-disember-2020-mesyuarat-dimulakan-pada-pukul-10-00-pagi-doa-tuan-yang-di-pertua-mempengerusikan-mesyuarat-439684.webp)

Khamis, 10 Disember 2020 Mesyuarat Dimulakan Pada Pukul 10.00 Pagi DOA [Tuan Yang Di-Pertua Mempengerusikan Mesyuarat]

Naskhah belum disemak PENYATA RASMI PARLIMEN DEWAN RAKYAT PARLIMEN KEEMPAT BELAS PENGGAL KETIGA MESYUARAT KETIGA Bil. 51 Khamis 10 Disember 2020 K A N D U N G A N JAWAPAN-JAWAPAN MENTERI BAGI PERTANYAAN-PERTANYAAN (Halaman 1) JAWAPAN-JAWAPAN LISAN BAGI PERTANYAAN-PERTANYAAN (Halaman 7) RANG UNDANG-UNDANG DIBAWA KE DALAM MESYUARAT (Halaman 21) RANG UNDANG-UNDANG: Rang Undang-undang Perbekalan 2021 Jawatankuasa:- Jadual:- Kepala B.45 (Halaman 23) Kepala B.46 (Halaman 52) Kepala B.47 (Halaman 101) USUL-USUL: Usul Anggaran Pembangunan 2021 Jawatankuasa:- Kepala P.45 (Halaman 23) Kepala P.46 (Halaman 52) Kepala P.47 (Halaman 101) Meminda Jadual Di Bawah P.M. 57(2) – Mengurangkan RM45 juta Daripada Peruntukan Kepala B.47 (Halaman 82) Waktu Mesyuarat dan Urusan Dibebaskan Daripada Peraturan Mesyuarat (Halaman 83) Meminda Jadual Di Bawah P.M. 66(9) – Mengurangkan RM85,549,200 Daripada Peruntukan Kepala B.47 (Halaman 102) DR. 10.12.2020 1 MALAYSIA DEWAN RAKYAT PARLIMEN KEEMPAT BELAS PENGGAL KETIGA MESYUARAT KETIGA Khamis, 10 Disember 2020 Mesyuarat dimulakan pada pukul 10.00 pagi DOA [Tuan Yang di-Pertua mempengerusikan Mesyuarat] JAWAPAN-JAWAPAN MENTERI BAGI PERTANYAAN-PERTANYAAN Tuan Karupaiya a/l Mutusami [Padang Serai]: Tuan Yang di-Pertua, saya minta dua minit, saya ada masalah di kawasan saya. Dua minit. Terima kasih Tuan Yang di-Pertua. Padang Serai ingin sampaikan masalah-masalah rakyat di kawasan, terutama sekali PKPD telah dilanjutkan di Taman Bayam, Taman Kangkung 1 dan 2, Taman Cekur Manis, Taman Sedeli Limau, Taman Bayam Indah, Taman Halia dan Taman Kubis di kawasan Paya Besar. Parlimen Padang Serai hingga 24 Disember 2020 iaitu selama empat minggu. -

155KB***The Courts and the Enforcement of Human Rights

(2020) 32 SAcLJ 458 THE COURTS AND THE ENFORCEMENT OF HUMAN RIGHTS This article examines how the Malaysian courts have dealt with substantive human rights issues in the cases that have come before them, focusing particularly on the last ten years. It highlights cases where the courts demonstrated greater willingness to review executive action and parliamentary legislation and test them against constitutional provisions that protect fundamental liberties such as the right to life, and freedom of expression, association and assembly. It also looks at cases which have taken a less flexible approach on these issues. The article also touches on the issues of access to justice, locus standi and justiciability of cases involving human rights issues before the Malaysian courts. Ambiga SREENEVASAN1 LLB (Exeter); Barrister-at-law (non-practising) (Gray’s Inn); Advocate and Solicitor (High Court in Malaya). DING Jo-Ann LLB (Manchester), MSt in International Human Rights Law (Oxford); Barrister-at-law (non-practising) (Lincoln’s Inn). Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world, Whereas disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind, and the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the common people …[2] 1 Former President of the Malaysian Bar (2007–2009), former chairperson and co-chairperson of the Coalition for Clean and Fair Elections (Bersih 2.0) (2010–2013), former president of the National Human Rights Society (Hakam) (2014–2018), Commissioner of the International Commission of Jurists. -

For Review Onlynik NAZMI NIK AHMAD the Post-2018 Order Is an Exciting Time of Possibilities for Malaysia

9mm NIK NAZMI AHMAD With a New Preface and Postscript by the Author For Review onlyNIK NAZMI NIK AHMAD The post-2018 order is an exciting time of possibilities for Malaysia. For the country’s Malay community to face new challenges of the 21st century and thrive, it has to look forward and forge ahead in a progressive manner. In this updated edition of Moving Forward, Nik Nazmi pushes for a paradigm that is comfortable with diversity and democracy. With the world changing and new problems to confront, Malaysia is brought to a crossroads. The choice is clear: a limbo of mediocrity with eventual decline looming, or to move forward “In search of answers to educationally, economically, politically and socially. the questions concerning Malays and Malayness, This edition of Moving Forward includes a new preface and postscript this young writer breaks to reflect on what Malaysians have achieved and cast an eye on the free from the stereotypical challenges that lie ahead. FORWARD MOVING mindsets that have plagued the discourse. This is the voice of conscience of a young Malay progressive. “Nik Nazmi represents a refreshing brand of Malay politics: ” middle-of-the-road, confident, unafraid and bold.” – Anwar Ibrahim – Karim Raslan, CEO of the KRA Group “Nik Nazmi is a refreshing voice. He has some profound observations and perspectives that belie his age and political youth.” – M. Bakri Musa, author of The Malay Dilemma Revisited Nik Nazmi Nik Ahmad read law at King’s College London before becoming private secretary to Anwar Ibrahim. In the 2008 general election, he was the youngest elected representative when he won the Seri Setia state seat in Selangor. -

Rafizi Wants PKR Reps Besides Azizah to Decline Malaysiakini.Com Aug 29, 2014

Rafizi wants PKR reps besides Azizah to decline MalaysiaKini.com Aug 29, 2014 PKR vice-president Rafizi Ramli today congratulated newly-elected PKR youth chief Nik Nazmi Nik Ahmad for declining PAS Youth's suggestion to nominate him for the Selangor menteri besar post. Rafizi also lauded Nik Nazmi's (left) statement calling on all PKR Selangr assemblyperson from the party to do likewise through open statements. This would be in line with the party's "unanimous decision" on Wan Azizah, Rafizi said. "As such, I call upon all assemblypersons from PKR to make an open statement to reject any nomination for the post of menteri besar by any party as a means to respect the PKR leadership decision," he said. The call follows the Selangor palace's request for Pakatan parties to submit more than two names for the post, and PAS' insistence that it would put up at least two from PKR for the post. While Selangor Menteri Besar Abdul Khalid Ibrahim has finally tendered his resignation after failing to get the support of the majority of the state assemblypersons, the crisis is far from over. This is due to PAS' shifting stand on Khalid's replacement, despite a consensus agreement being beached at a Pakatan leadership meeting on Aug 17. While the outcome of the meeting was that Wan Azizah will be the sole candidate from Pakatan to be proposed to the palace, the sultan's request for multiple names has put PAS at odds with its coalition partners. Nik Nazmi: Thanks but no thanks Earlier today Nik Nazmi said he was grateful that PAS wants to nominate him soon as possible as Selangor menteri besar but he remains committed to supporting Wan Azizah's nomination. -

Open LIM Doctoral Dissertation 2009.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Communications BLOGGING AND DEMOCRACY: BLOGS IN MALAYSIAN POLITICAL DISCOURSE A Dissertation in Mass Communications by Ming Kuok Lim © 2009 Ming Kuok Lim Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2009 The dissertation of Ming Kuok Lim was reviewed and approved* by the following: Amit M. Schejter Associate Professor of Mass Communications Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Richard D. Taylor Professor of Mass Communications Jorge R. Schement Distinguished Professor of Mass Communications John Christman Associate Professor of Philosophy, Political Science, and Women’s Studies John S. Nichols Professor of Mass Communications Associate Dean for Graduate Studies and Research *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT This study examines how socio-political blogs contribute to the development of democracy in Malaysia. It suggests that blogs perform three main functions, which help make a democracy more meaningful: blogs as fifth estate, blogs as networks, and blogs as platform for expression. First, blogs function as the fifth estate performing checks-and-balances over the government. This function is expressed by blogs’ role in the dissemination of information, providing alternative perspectives that challenge the dominant frame, and setting of news agenda. The second function of blogs is that they perform as networks. This is linked to the social-networking aspect of the blogosphere both online and offline. Blogs also have the potential to act as mobilizing agents. The mobilizing capability of blogs facilitated the mass street protests, which took place in late- 2007 and early-2008 in Malaysia. -

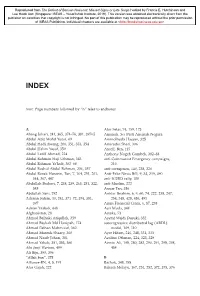

Page Numbers Followed by “N” Refer to Endnotes. a Abang Johari, 241, 365

INDEX Note: Page numbers followed by “n” refer to endnotes. A Alor Setar, 74, 159, 173 Abang Johari, 241, 365, 374–76, 381, 397n5 Amanah. See Parti Amanah Negara Abdul Aziz Mohd Yusof, 69 Aminolhuda Hassan, 325 Abdul Hadi Awang, 206, 351, 353, 354 Amirudin Shari, 306 Abdul Halim Yusof, 359 Ansell, Ben, 115 Abdul Latiff Ahmad, 224 Anthony Nogeh Gumbek, 382–83 Abdul Rahman Haji Uthman, 343 anti-Communist Emergency campaigns, Abdul Rahman Ya’kub, 367–68 210 Abdul Rashid Abdul Rahman, 356, 357 anti-corruption, 140, 238, 326 Abdul Razak Hussein, Tun, 7, 164, 251, 261, Anti-Fake News Bill, 9, 34, 319, 490 344, 367, 447 anti-ICERD rally, 180 Abdullah Badawi, 7, 238, 239, 263, 281, 322, anti-Muslim, 222 348 Anuar Tan, 356 Abdullah Sani, 292 Anwar Ibrahim, 6, 9, 60, 74, 222, 238, 247, Adenan Satem, 10, 241, 371–72, 374, 381, 254, 348, 428, 486, 491 397 Asian Financial Crisis, 6, 87, 238 Adnan Yaakob, 448 Asri Muda, 344 Afghanistan, 28 Astaka, 73 Ahmad Baihaki Atiqullah, 359 Asyraf Wajdi Dusuki, 352 Ahmad Bashah Md Hanipah, 174 autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) Ahmad Fathan Mahmood, 360 model, 109, 110 Ahmad Marzuk Shaary, 360 Ayer Hitam, 246, 248, 331, 333 Ahmad Nazib Johari, 381 Azalina Othman, 224, 323, 329 Ahmad Yakob, 351, 353, 360 Azmin Ali, 195, 280, 283, 290, 291, 295, 298, Aku Janji Warisan, 409 454 Ali Biju, 390, 396 “Allah ban”, 375 B Alliance-BN, 4, 5, 191 Bachok, 348, 355 Alor Gajah, 222 Bahasa Melayu, 167, 251, 252, 372, 375, 376 19-J06064 24 The Defeat of Barisan Nasional.indd 493 28/11/19 11:31 AM 494 Index Bakun Dam, 375, 381 parliamentary seats, 115, 116 Balakong, 296, 305 police and military votes, 74 Balakrishna, Jay, 267 redelineation exercise, 49, 61, 285–90 Bandar Kuching, 59, 379–81, 390 in Sabah, 402, 403 Bangi, 69, 296 in Sarawak, 238, 246, 364, 374–78 Bangsa Johor, 439–41 Sarawak BN. -

Suara Rakyat Malaysia (SUARAM) Is Committed to Defending and Campaigning for Human Rights in Malaysia and Other Parts of the World

Suara Rakyat Malaysia (SUARAM) is committed to defending and campaigning for human rights in Malaysia and other parts of the world. The organisation began in 1989 as a campaign body for the abolition of the Internal Security Act (ISA) in the aftermath of the infamous Operasi Lalang when 106 Malaysians were detained without trial. Since then, it has evolved into the leading human rights organisation in Malaysia, committed to protecting, preserving and promoting human rights. Produced by: Suara Rakyat Malaysia (SUARAM) Suara Inisiatif Sdn Bhd (562530-P) Office Address: 433A, Jalan 5/46, Malaysia: Gasing Indah, 46000 Petaling Jaya, Human Rights Selangor, Malaysia. Report 2014 Tel: +603 - 7784 3525 Fax: +603 - 7784 3526 OVERVIEW Email: [email protected] www.suaram.net Photo credit: Victor Chin, Rakan Mantin. MALAYSIA: HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT OVERVIEW 2014 1 Suara Rakyat Malaysia (SUARAM) CONTENTS Introduction 2 Detention Without Trial 4 Police Abuses of Power 6 Freedom of Expression and Information 10 Freedom of Assembly 14 Freedom of Association 16 Freedom of Religion 18 Refugees, Asylum Seekers and Migrant Workers 23 Death Penalty 27 Free and Fair Elections 27 Corruption and Accountability 30 Law and the Judiciary 32 Human Rights Commission of Malaysia (SUHAKAM) 36 MALAYSIA: HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT OVERVIEW 2014 2 Suara Rakyat Malaysia (SUARAM) INTRODUCTION In 2014, the human rights record under the Najib Razak administration has hit a new low. When he first came to power in 2009, Najib Razak introduced several reforms in an attempt to win back votes after the fiasco for the ruling coalition in the 2008 general election. This attempt at reform has been reversed after yet another debacle for BN in the 2013 general election, epitomized by the about-turn decision on the promise to repeal the Sedition Act, with the Prime Minister seemingly bowing down to demands of extremist groups for his own political survival and bent on teaching dissenting voters a lesson. -

Applause for Rosmah at PKR Ceramah Malaysiakini.Com February 2, 2011

Applause for Rosmah at PKR ceramah Malaysiakini.com February 2, 2011 Despite it being a PKR ceramah, last night's maiden run of the party's leadership roadshow saw the premier's wife Rosmah Mansor receiving the most applause, or perhaps somewhat polite jeers, from the thousand-strong crowd of opposition supporters. Rosmah's name was constantly on the lips of the eight Pakatan leaders who spoke at the party's ceramah in Petaling Jaya, though mostly to her disadvantage, as the speakers took turns to make jibes at her expense, to the laughter of the crowd. Mostly they made fun of her continual claim to be the 'first lady' of Malaysia despite clear protocol and conventions against it. “They say that BN is the government of Bini Najib,” said PKR de facto leader Anwar Ibrahim, who spoke at the event, inducing more laughter. Shouts of beruk, the Malay word for simians like baboons and monkeys, kept being heard as overenthusiastic supporters reacted to Anwar's pun on the government's alphabet soup of programs like ETP and NKRA, equating it to K-E-R-A or kera, another Malay word for the simian species. Other speakers included PAS Shah Alam MP Khalid Samad, DAP Puchong parliamentarian Gobind Singh Deo, Lembah Pantai parliamentarian Nurul Izzah Anwar, Seri Setia assemblyperson Nik Nazmi Nik Ahmad, Selangor deputy speaker Haniza Talha, Petaling Jaya Selatan MP Hee Loy Sian and Batu parliamentarian Tian Chua. A picture of Rosmah was constantly flashed on the backdrop of the stage with less than flattering captions as each of them commented on her. -

Tan Sri Hasmy Agam

For Immediate Release Malaysia: Asian human rights groups and activists urge the Prime Minister to halt crackdown on freedom of expression (Bangkok, 26 February 2015) – The human rights community in Asia has raised concern over the continued crackdown on freedom of expression in Malaysia, in an open letter addressed to the Prime Minister of Malaysia and signed by the Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA) together with 23 other human rights organisations and activists today. The groups and activists also urged the government to cease all forms of harassment against individuals who hold dissenting opinion from that of the current administration, and to repeal all repressive laws, including the colonial era Sedition Act 1948, echoing previous similar calls made by both the international community and within the country. The signatories of the open letter, comprising human rights groups and activists from Bangladesh, Burma, Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mongolia, Pakistan, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Timor Leste, as well as regional organisations, registered alarm over the government’s continued abuse of this legislation, as in the recent conviction of the activist Hishamuddin Rais, who questioned the legitimacy of the 13th General Election results and urged the public to reject the newly-elected government; and the arrest and charges against human rights lawyer Eric Paulsen, after a Twitter post criticising the Malaysian Islamic Development Department for spreading extremism through Friday sermons. The letter, initiated by Bangkok-based regional human rights group, FORUM-ASIA, also deplored the latest arrests and investigations against those who criticised or commented on the Federal Court’s decision to uphold the conviction of Anwar Ibrahim of sodomy charges earlier this month. -

Anwar Supporters Try to Storm Barricade Malaysiakini.Com Oct 29, 2014

Anwar supporters try to storm barricade MalaysiaKini.com Oct 29, 2014 Yet another scuffle broke out at the second day of Opposition Leader Anwar Ibrahim's Sodomy II appeal, as his supporters tried to storm through the barricade outside the Palace of Justice in Putrajaya. The incident took place around 8.38am, shortly after some 500 supporters arrived outside the court complex after marching from the Tuanku Mizan Zainal Abidin Mosque. As soon as the procession, led by PKR vice-president Tian Chua and PKR Youth chief Nik Nazmi Nik Ahmad arrived outside the court house, some supporters shouted for “pushing through” the barricade, with a chaotic scene ensuing for some 10 minutes. Tian Chua and Nik Nazmi were also spotted trying to push through the barricade with other supporters, but some 50 police officers quickly moved in to prevent a breach. Makeshift stage attraction Shortly after, Nik Nazmi urged supporters to calm down before passing through the barricade with Tian Chua to negotiate with the police. They requested that the supporters be allowed to gather directly in front of the Palace of Justice, which the police refused to allow. The crowd later calmed down as the PKR leaders began to make speeches from a truck that was used as a makeshift stage. Yesterday, many of Anwar’s supporters had gathered under a large canopy erected on Persiaran Perdana, especially when it started to rain late in the day. Today however, that area is cordoned off. By mid day, Anwar's supporters outside the court complex had swelled to almost 1,000 Speaking to Malaysiakini later, Nik Nzmi said he did not intend to breach the barricade but was "trapped" in the middle when the crowd started pushing. -

Penyata Rasmi Parlimen Dewan Rakyat Parlimen Keempat Belas Penggal Kedua Mesyuarat Kedua

Naskhah belum disemak PENYATA RASMI PARLIMEN DEWAN RAKYAT PARLIMEN KEEMPAT BELAS PENGGAL KEDUA MESYUARAT KEDUA Bil. 26 Selasa 9 Julai 2019 K A N D U N G A N JAWAPAN-JAWAPAN MENTERI BAGI PERTANYAAN-PERTANYAAN (Halaman 1) JAWAPAN-JAWAPAN LISAN BAGI PERTANYAAN-PERTANYAAN (Halaman 12) PEMASYHURAN DARIPADA TUAN YANG DI-PERTUA: - Ucapan Takziah Kepada Keluarga Mendiang Datuk Seri Dr James Dawos Mamit (Halaman 48) RANG UNDANG-UNDANG DIBAWA KE DALAM MESYUARAT (Halaman 50) USUL: Waktu Mesyuarat dan Urusan Dibebaskan Daripada Peraturan Mesyuarat (Halaman 50) RANG UNDANG-UNDANG: Rang Undang-undang Perikanan Pindaan) 2019 (Halaman 51) DR. 9.7.2019 1 MALAYSIA DEWAN RAKYAT PARLIMEN KEEMPAT BELAS PENGGAL KEDUA MESYUARAT KEDUA Selasa, 9 Julai 2019 Mesyuarat dimulakan pada pukul 10.00 pagi DOA [Timbalan Yang di-Pertua (Tuan Nga Kor Ming) mempengerusikan Mesyuarat] JAWAPAN-JAWAPAN MENTERI BAGI PERTANYAAN-PERTANYAAN 1. Tuan Haji Akmal Nasrullah bin Mohd Nasir [Johor Bahru] minta Menteri Perdagangan Dalam Negeri dan Hal Ehwal Pengguna menyatakan sejauh manakah keberkesanan Tribunal Tuntutan Pengguna Malaysia (TTPM) di dalam membantu rakyat Malaysia yang terbabit di dalam kes-kes penipuan seperti pakej pelancongan. Menteri Perdagangan Dalam Negeri dan Hal Ehwal Pengguna [Datuk Seri Saifuddin Nasution bin Ismail]: Terima kasih Tuan Yang di-Pertua, terima kasih sahabat saya dari Johor Bahru. Untuk makluman Ahli-ahli Yang Berhormat khususnya Johor Bahru, di bawah kementerian ini ada satu akta namanya Akta Perlindungan Pengguna 1999. Dalam akta itu ada satu seksyen iaitu seksyen 85, seksyen inilah yang melahirkan Tribunal Tuntutan Pengguna Malaysia. Tujuannya ialah menjadi satu saluran alternatif kepada rakyat yakni pengguna untuk mereka failkan tuntutan tebus rugi berkenaan pembelian barangan, kalau mereka rasa tertipu dan juga perkhidmatan yang dibekalkan oleh peniaga atau pembekal perkhidmatan. -

Parlimen Keempat Belas Penggal Kedua Mesyuarat Kedua

Naskhah belum disemak PARLIMEN KEEMPAT BELAS PENGGAL KEDUA MESYUARAT KEDUA Bil. 21 Isnin 1 Julai 2019 K A N D U N G A N MENGANGKAT SUMPAH: - Yang Berhormat Cik Vivian Wong Shir Yee (Sandakan) (Halaman 1) PEMASYHURAN TUAN YANG DI-PERTUA: - Mengalu-alukan Ahli Baru (Halaman 1) - Memperkenankan Akta-akta (Halaman 2) - Perutusan Daripada Dewan Negara (Halaman 2) UCAPAN TAKZIAH KEPADA KE BAWAH DULI YANG MAHA MULIA SERI PADUKA BAGINDA YANG DI-PERTUAN AGONG DAN SELURUH KERABAT ATAS KEMANGKATAN KE BAWAH DULI YANG MAHA MULIA PADUKA AYAHANDA SULTAN HAJI AHMAD SHAH AL-MUSTA’IN BILLAH IBNI ALMARHUM SULTAN ABU BAKAR RI’AYATUDDIN AL-MUADZAM SHAH (Halaman 3) JAWAPAN-JAWAPAN LISAN BAGI PERTANYAAN-PERTANYAAN (Halaman 4) RANG UNDANG-UNDANG DIBAWA KE DALAM MESYUARAT (Halaman 42) USUL: Waktu Mesyuarat dan Urusan Dibebaskan Daripada Peraturan Mesyuarat (Halaman 43) USUL MENTERI DI JABATAN PERDANA MENTERI DI BAWAH P.M. 27(3): ■ Pengisytiharan Harta Semua Ahli Dewan Rakyat (Halaman 43) DR.1.7.2019 1 MALAYSIA DEWAN RAKYAT PARLIMEN KEEMPAT BELAS PENGGAL KEDUA MESYUARAT KEDUA Isnin, 1 Julai 2019 Mesyuarat dimulakan pada pukul 10.00 pagi DOA [Tuan Yang di-Pertua mempengerusikan Mesyuarat] MENGANGKAT SUMPAH Ahli Yang Berhormat yang tersebut di bawah ini telah mengangkat sumpah: - Yang Berhormat Cik Vivian Wong Shir Yee [Sandakan] PEMASYHURAN TUAN YANG DI-PERTUA MENGALU-ALUKAN AHLI-AHLI BARU Tuan Yang di-Pertua: Bismillahir Rahmanir Rahim. Assalamualaikum warahmatullahi wabarakatuh dan salam sejahtera. Ahli-ahli Yang Berhormat, saya mengucapkan tahniah kepada Yang Berhormat Cik Vivian Wong Shir Yee, Ahli Parlimen Sandakan yang telah mengangkat sumpah sebentar tadi. Saya juga mengucapkan tahniah kepada Yang Berhormat yang telah memenangi Pilihan Raya Kecil Sandakan pada Sabtu, 11 Mei 2019 yang lalu.