Gulf Plains Planned Burn Guideline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nature of Northern Australia

THE NATURE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA Natural values, ecological processes and future prospects 1 (Inside cover) Lotus Flowers, Blue Lagoon, Lakefield National Park, Cape York Peninsula. Photo by Kerry Trapnell 2 Northern Quoll. Photo by Lochman Transparencies 3 Sammy Walker, elder of Tirralintji, Kimberley. Photo by Sarah Legge 2 3 4 Recreational fisherman with 4 barramundi, Gulf Country. Photo by Larissa Cordner 5 Tourists in Zebidee Springs, Kimberley. Photo by Barry Traill 5 6 Dr Tommy George, Laura, 6 7 Cape York Peninsula. Photo by Kerry Trapnell 7 Cattle mustering, Mornington Station, Kimberley. Photo by Alex Dudley ii THE NATURE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA Natural values, ecological processes and future prospects AUTHORS John Woinarski, Brendan Mackey, Henry Nix & Barry Traill PROJECT COORDINATED BY Larelle McMillan & Barry Traill iii Published by ANU E Press Design by Oblong + Sons Pty Ltd The Australian National University 07 3254 2586 Canberra ACT 0200, Australia www.oblong.net.au Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au Printed by Printpoint using an environmentally Online version available at: http://epress. friendly waterless printing process, anu.edu.au/nature_na_citation.html eliminating greenhouse gas emissions and saving precious water supplies. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry This book has been printed on ecoStar 300gsm and 9Lives 80 Silk 115gsm The nature of Northern Australia: paper using soy-based inks. it’s natural values, ecological processes and future prospects. EcoStar is an environmentally responsible 100% recycled paper made from 100% ISBN 9781921313301 (pbk.) post-consumer waste that is FSC (Forest ISBN 9781921313318 (online) Stewardship Council) CoC (Chain of Custody) certified and bleached chlorine free (PCF). -

An Assessment of Agricultural Potential of Soils in the Gulf Region, North Queensland

REPORT TO DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES REGIONAL INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT (RID), NORTH REGION ON An Assessment of Agricultural Potential of Soils in the Gulf Region, North Queensland Volume 1 February 1999 Peter Wilson (Land Resource Officer, Land Information Management) Seonaid Philip (Senior GIS Technician) Department of Natural Resources Resource Management GIS Unit Centre for Tropical Agriculture 28 Peters Street, Mareeba Queensland 4880 DNRQ990076 Queensland Government Technical Report This report is intended to provide information only on the subject under review. There are limitations inherent in land resource studies, such as accuracy in relation to map scale and assumptions regarding socio-economic factors for land evaluation. Before acting on the information conveyed in this report, readers should ensure that they have received adequate professional information and advice specific to their enquiry. While all care has been taken in the preparation of this report neither the Queensland Government nor its officers or staff accepts any responsibility for any loss or damage that may result from any inaccuracy or omission in the information contained herein. © State of Queensland 1999 For information about this report contact [email protected] ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The authors thank the input of staff of the Department of Natural Resources GIS Unit Mareeba. Also that of DNR water resources staff, particularly Mr Jeff Benjamin. Mr Steve Ockerby, Queensland Department of Primary Industries provided invaluable expertise and advice for the development of the agricultural suitability assessment. Mr Phil Bierwirth of the Australian Geological Survey Organisation (AGSO) provided an introduction to and knowledge of Airborne Gamma Spectrometry. Assistance with the interpretation of AGS data was provided through the Department of Natural Resources Enhanced Resource Assessment project. -

Land Zones of Queensland

P.R. Wilson and P.M. Taylor§, Queensland Herbarium, Department of Science, Information Technology, Innovation and the Arts. © The State of Queensland (Department of Science, Information Technology, Innovation and the Arts) 2012. Copyright inquiries should be addressed to <[email protected]> or the Department of Science, Information Technology, Innovation and the Arts, 111 George Street, Brisbane QLD 4000. Disclaimer This document has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within this document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. Information contained in this document is from a number of sources and, as such, does not necessarily represent government or departmental policy. If you need to access this document in a language other than English, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone Library Services on +61 7 3224 8412. This publication can be made available in an alternative format (e.g. large print or audiotape) on request for people with vision impairment; phone +61 7 3224 8412 or email <[email protected]>. ISBN: 978-1-920928-21-6 Citation This work may be cited as: Wilson, P.R. and Taylor, P.M. (2012) Land Zones of Queensland. Queensland Herbarium, Queensland Department of Science, Information Technology, Innovation and the Arts, Brisbane. 79 pp. Front Cover: Design by Will Smith Images – clockwise from top left: ancient sandstone formation in the Lawn Hill area of the North West Highlands bioregion – land zone 10 (D. -

Western Queensland

Western Queensland - Gulf Plains, Northwest Highlands, Mitchell Grass Downs and Channel Country Bioregions Strategic Offset Investment Corridors Methodology Report April 2016 Prepared by: Strategic Environmental Programs/Conservation and Sustainability Services, Department of Environment and Heritage Protection © State of Queensland, 2016. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence. Under this licence you are free, without having to seek our permission, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. For more information on this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Disclaimer This document has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within this document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. Information contained in this document is from a number of sources and, as such, does not necessarily represent government or departmental policy. If you need to access this document in a language other than English, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone Library Services on +61 7 3170 5470. This publication can be made available in an alternative format (e.g. large print or audiotape) on request for people with vision impairment; phone +61 7 3170 5470 or email <[email protected]>. -

Arsbc-2008-Williams2 Paper.Pdf

BIOGEOGRAPHY AND BIODIVERSITY OF BIOLOGICAL SOIL CRUSTS ACROSS QUEENSLAND Wendy J. Williams1, Burkhard Büdel2, *Colin Driscoll3 1The University of Queensland, Gatton, Queensland, 4343, Australia; 2Department of Biology, University of Kaiserslautern, Kaiserslautern, Germany 3The University of Newcastle, NSW, 2308, Australia Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Recent field research has established that biological soil crust communities (cyanobacteria, lichens, liverworts and mosses) are widespread across the rangelands of Queensland. Our survey has covered many national parks and reserves or private properties where necessary, to take in changes in rainfall gradients, vegetation communities and soils. We document for the first time, well-established and extensive cyanobacteria-dominated soil crusts occurring throughout much of the gulf-savannah. An ecologically important biological crust system was found across a fragile dune and flood plain near Skull Hole, Bladensburg NP. Other noteworthy biological crusts with significant biodiversity and cover were found in the jump-ups Diamantina NP; Spinifex ridges, Minerva Hills NP; Grey Range (west of Thargomindah); Sturt Stony Desert (Arrabury region); Stony plains (Coorabulka, Windorah Rd) and Arcadia Valley (Old Towrie). There were considerable and diverse cyanobacteria-dominated soil crusts found south-east of Cunnamulla (Glencoban), Currawinya NP, Bindegolly NP, Boodjamulla NP (Lawn Hill Gorge and Riversleigh sections), sand dunes (various sites, far western QLD) and in the estuarine sand-flats around Karumba. Across western QLD several mesas were surveyed. There were also good representations of hypolithic (cyanobacteria - under quartz, Boulia-Djarra Rd), epilithic (cyanobacteria and lichens) and endolithic (cyanobacteria) communities on various granite or sandstone rocky outcrops. Early results clearly show these biogenic soil crusts are unique in their biodiversity, structure and function. -

Koala Context

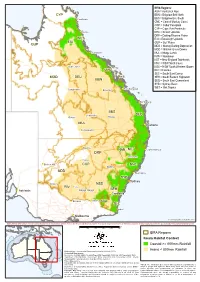

IBRA Regions: AUA = Australian Alps CYP BBN = Brigalow Belt North )" Cooktown BBS = Brigalow Belt South CMC = Central Mackay Coast COP = Cobar Peneplain CYP = Cape York Peninsula ") Cairns DEU = Desert Uplands DRP = Darling Riverine Plains WET EIU = Einasleigh Uplands EIU GUP = Gulf Plains GUP MDD = Murray Darling Depression MGD = Mitchell Grass Downs ") Townsville MUL = Mulga Lands NAN = Nandewar NET = New England Tablelands NNC = NSW North Coast )" Hughenden NSS = NSW South Western Slopes ") CMC RIV = Riverina SEC = South East Corner MGD DEU SEH = South Eastern Highlands BBN SEQ = South East Queensland SYB = Sydney Basin ") WET = Wet Tropics )" Rockhampton Longreach ") Emerald ") Bundaberg BBS )" Charleville )" SEQ )" Quilpie Roma MUL ") Brisbane )" Cunnamulla )" Bourke NAN NET ") Coffs Harbour DRP ") Tamworth )" Cobar ") Broken Hill COP NNC ") Dubbo MDD ") Newcastle SYB ") Sydney ") Mildura NSS RIV )" Hay ") Wagga Wagga SEH Adelaide ") ") Canberra ") ") Echuca Albury AUA SEC )" Eden ") Melbourne © Commonwealth of Australia 2014 INDICATIVE MAP ONLY: For the latest departmental information, please refer to the Protected Matters Search Tool and the Species Profiles & Threats Database at http://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/threatened/index.html km 0 100 200 300 400 500 IBRA Regions Koala Habitat Context Coastal >= 800mm Rainfall Produced by: Environmental Resources Information Network (2014) Inland < 800mm Rainfall Contextual data source: Geoscience Australia (2006), Geodata Topo 250K Topographic Data and 10M Topographic Data. Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (2012). Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia (IBRA), Version 7. Other data sources: Commonwealth of Australia, Bureau of Meteorology (2003). Mean annual rainfall (30-year period 1961-1990). Caveat: The information presented in this map has been provided by a Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (2013). -

State Coastal Management Plan

Schedule 1: Regional overviews The Queensland coast has been subdivided into eleven coastal regions for the purpose of preparing regional coastal plans. The regions’ boundaries are based on coastal local government boundaries. The overview for each region generally describes the region, its coastal resources, existing management and administration arrangements, and the key coastal management issues.18 The eleven coastal regions are illustrated in map 1. Map 3 shows the terrestrial and marine bioregions referred to in this schedule. Marine Terrestrial 145 E 140 E yy Arafura 1 Cape York Peninsula Carpentaria 2 Gulf Plains yy 10 S 1 1 Wellesley 3 Einasleigh Uplands Karumba-Nassau 4 Wet Tropical Rainforest yy yyyyyyyyy West Cape York 5 Mount Isa Inlier 1 Torres Strait 6 Gulf Fall Upland yy yyyyyyyyy | 1 East Cape York 7 Mitchell Grass Downs Weipa Ribbons 8 yyyyyyyyy Brigalow Belt North 1 1 Wet Tropic Coast 9 Central Queensland Coast Coen yyyyyyyyyy1 yyCentral Reef 10 Desert Uplands Lucinda-Mackay Coast 11 South Brigalow 1 1 yyyyyyy1 Mackay-Capricorn 12 South-east Queensland 15 S 1 1 Cooktown Pompey-Swains 13 Simpson-Strzelecki Dunefields yyyyyyyyyyyyyyy 2 4 Shoalwater Coast 14 NSW North Coast 3 Tweed-Moreton 2 2 15 Darling-Riverine Plain yyyyyy yyyCairns yy zy 2 Outer Provinces 2 16 New England Tableland 2 Atherton 4 6 2 Normanton 17 3 4 Nandewar yyyBurketownyyy yyy 2 3 18 Channel Country 6 Einasleigh 4 2 3 Ingham 2 19 Mulga Lands yyyyyyyy 2 3 5 3 Townsville {|{ 2 Ayr 5 2 yyyyyCharters Towers 8 20 S 3 Bowen 20 -

Human Refugia in Australia During the Last Glacial Maximum and Terminal Pleistocene: a Geospatial Analysis of the 25E12 Ka Australian Archaeological Record

Journal of Archaeological Science 40 (2013) 4612e4625 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Archaeological Science journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/jas Human refugia in Australia during the Last Glacial Maximum and Terminal Pleistocene: a geospatial analysis of the 25e12 ka Australian archaeological record Alan N. Williams a,*, Sean Ulm b, Andrew R. Cook c, Michelle C. Langley d, Mark Collard e a Fenner School of Environment and Society, The Australian National University, Building 48, Linnaeus Way, Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia b Department of Anthropology, Archaeology and Sociology, School of Arts and Social Sciences, James Cook University, PO Box 6811, Cairns, QLD 4870, Australia c School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, The University of New South Wales, NSW 2052, Australia d Institute of Archaeology, University of Oxford, Oxford OX1 2PG, United Kingdom e Human Evolutionary Studies Program and Department of Archaeology, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada article info abstract Article history: A number of models, developed primarily in the 1980s, propose that Aboriginal Australian populations Received 13 February 2013 contracted to refugia e well-watered ranges and major riverine systems e in response to climatic Received in revised form instability, most notably around the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) (w23e18 ka). We evaluate these 3 June 2013 models using a comprehensive continent-wide dataset of archaeological radiocarbon ages and geospatial Accepted 17 June 2013 techniques. Calibrated median radiocarbon ages are allocated to over-lapping time slices, and then K-means cluster analysis and cluster centroid and point dispersal pattern analysis are used to define Keywords: Minimum Bounding Rectangles (MBR) representing human demographic patterns. -

North Australian Pastoralists and Graziers Are Ready for Contractual Biodiversity Conservation

North Australian pastoralists and graziers are ready for contractual biodiversity conservation Romy Greiner Charles Darwin University 28 April 2014 All photographs taken by the presenter unless otherwise attributed Purpose of the research . Develop a grazing industry perspective: Snapshot of what graziers and pastoralists think. Conservation for enterprise/income diversification? What conservation models would work? Where? How? What are preferred contractual conditions? . Establish foundation for a strategic industry position on potential supply of environmental services. Enhance the ability of potential investors to understand the needs of pastoralists. Support market formation and negotiations about the provision of contractual biodiversity conservation by pastoralists. Research area Bioregions as per colloquial reference but aligned with interim biogeographic regionalisation for Australia, version 7 (DE, 2013); E.U.=’Einasleigh Uplands’; V.R.D.=’Victoria River District’. ‘Einasleigh Uplands’ also includes directly adjacent areas of Cape York and Desert Uplands; ‘Gulf Plains’ also includes Mount Isa Inlier and parts of Mitchell Grass Downs; ‘Barkly’ comprises western parts of Mitchell Grass Downs, Davenport Murchison Ranges and eastern parts of Tanami; ‘Sturt’ also includes western parts of Gulf Falls and Uplands; Victoria River District’ comprises Ord Victoria Plain and Victoria Bonaparte; ‘Kimberley’ comprises Northern Kimberley, Central Kimberley and Dampierland. Survey response Total QLD NT WA (n=104) (n=61) (n=25) (n=18) Property -

Australia's 89 Bioregions (PDF

ARC Arnhem Coast ARP Arnhem Plateau TIW AUA Australian Alps AVW Avon Wheatbelt BBN Brigalow Belt North DARWIN ! ARC BBS Brigalow Belt South BEL Ben Lomond ITI DAC PCK ARP BHC Broken Hill Complex CEA BRT Burt Plain CAR Carnarvon ARC CEA Central Arnhem DAB CYP CEK Central Kimberley CER Central Ranges NOK VIB CHC Channel Country CMC Central Mackay Coast GUC COO Coolgardie GFU STU COP Cobar Peneplain COS Coral Sea CEK CYP Cape York Peninsula OVP DAB Daly Basin DAC Darwin Coastal DAL WET GUP EIU DAL Dampierland DEU Desert Uplands DMR Davenport Murchison Ranges COS DRP Darling Riverine Plains DMR TAN EIU Einasleigh Uplands MII ESP Esperance Plains GSD EYB Eyre Yorke Block FIN Finke FLB Flinders Lofty Block CMC FUR Furneaux BRT GAS Gascoyne PIL DEU GAW Gawler MGD BBN GES Geraldton Sandplains GFU Gulf Fall and Uplands MAC GID Gibson Desert LSD GID GSD Great Sandy Desert GUC Gulf Coastal GUP Gulf Plains CAR GAS CER FIN CHC GVD Great Victoria Desert HAM Hampton ITI Indian Tropical Islands SSD JAF Jarrah Forest KAN Kanmantoo KIN King GVD LSD Little Sandy Desert STP BBS MUR SEQ MAC MacDonnell Ranges MUL MAL Mallee ! BRISBANE MDD Murray Darling Depression YAL MGD GES Mitchell Grass Downs STP MII Mount Isa Inlier MUL Mulga Lands NUL MUR Murchison NAN Nandewar GAW NET NCP Naracoorte Coastal Plain SWA COO NAN NET New England Tablelands AVW HAM BHC DRP NNC NSW North Coast FLB NOK Northern Kimberley ! COP PERTH NSS NSW South Western Slopes MDD NNC NUL Nullarbor MAL EYB OVP Ord Victoria Plain PCK Pine Creek JAF ESP SYB PSI PIL Pilbara ADELAIDE ! ! PSI Pacific -

Climate Change Report

CLIMATE CHANGE IN THE SOUTHERN GULF REGION: A background paper to inform the Southern Gulf Natural Resource Management Plan SUGGESTED CITATION Crowley, G.M. (2016) Climate change in the Southern Gulf region: A background paper to inform the Southern Gulf Natural Resource Management Plan. Southern Gulf Natural Resource Management, Mount Isa, Queensland. ISBN 978-0-9808776-3-2 This report is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. You are free to copy, communicate and adapt this work, so long as you attribute Southern Gulf NRM Inc. DISCLAIMER While every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of this publication Southern Gulf NRM accepts no liability for any loss or damage that result from reliance on it. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project was fund by the Australian Government’s Regional Natural Resource Management Planning for Climate Change Fund. My thanks go to Andrew Maclean (Southern Gulf NRM) for inviting me to undertake this project, and for providing guidance and feedback throughout. I also thank David Gillieson for his forbearance, proof-reading and GIS advice. Climate change in the Southern Gulf region: A background paper to inform the Southern Gulf Natural Resource Management Plan Gabriel Crowley April 2016 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The region of Indigenous people is one third that of non- Indigenous people. The Southern Gulf region is situated in the far north-west of Queensland and covers all Only a small proportion of pastoralists across catchments that drain into the southern Gulf of northern Australia possess characteristics to Carpentaria between Karumba and just west of make them resilient to major stresses and the Northern Territory border. -

AUSTRALIA– Country Data Dossier for Protected Areas Summary Sheet

Country data dossier for protected areas AUSTRALIA– Country Data Dossier for Protected Areas Summary Sheet Estimated current PA coverage (Source: DOPA, see footnote on next page) 14.61% Terrestrial (1 126 825 km2) 39.47% Marine (3 267 871 km2) Terrestrial and Marine Ecoregions Out of 41 terrestrial ecological regions: 14 ecological regions (Mitchell grass downs, Western Australian Mulga shrublands, Tirari-Sturt stony desert, Carpentaria tropical savanna, Kimberly tropical savanna, Brigalow tropical savanna, Southeast Australia temperate savanna, Eastern Australia mulga shrublands, Victoria Plains tropical savanna, Pilbara shrublands, Southwest Australia savanna, Einasleigh upland savanna, Carnarvon xeric shrublands, Mount Lofty woodlands) are the highest priority candidate sites for further protection. Out of 23 marine ecological regions: 2 ecological regions (Bassian, Cape Howe) are the highest priority candidate sites for further protection. Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas (IBAs) Australia has 309 IBAs: 71 IBAs have no protection, 152 IBAs have partial protection and 86 IBAs have complete protection. Bringing some IBAs that have no protection or having partial protection under protected areas and improving the management effectiveness of all IBA PAs are priority actions. Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas (IBAs) in Danger Out of the 4 IBAs in danger impacted by fire and fire suppression, residential and commercial development, and agriculture/aquaculture, 2 IBAs have little or no protection. Although 1 IBA is mostly protected and 1 IBA is fully protected, they face a number of threats. Bringing unprotected IBAs under protection either by expanding existing PAs or establishing new PAs and improving management effectiveness through addressing threats are potential further actions. Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites (AZEs) Australia has 17 AZEs: 2 AZEs have no protection, 2 AZEs have partial protection and 13 AZEs have complete protection.