Publish and Collaborate: an Invitation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parade-RGB.Pdf

CONTENTS WELCOME This year, we are proud to present a 06-33 Food & Travel 58-71 Home & Garden 108-111 Format fantastic and diverse line-up of new and We are delighted returning content that we will launch to 06-07 Inside the Box with Jack Stein our buyers at MIPCOM 2017. to welcome you to 58-59 Million Dollar House Hunters 108-109 Restaurant Revolution 08 Andy & Ben Eat Australia 60-61 Luxury Homes Revealed 110-111 Greatest Chefs Parade’s MIPCOM For this market we are bringing 160 hours 09 Andy & Ben Eat the World 62-63 Ready Set Reno of new content which includes a brand 10-11 Sara’s Australia Unveiled 64-65 Find Me a Home in the Country 2017 portfolio of hit new and exciting line-up of lifestyle and 12-13 United Plates of America 66 Australia’s Best Houses factual series being launched. series and originals 14-15 Justine’s Flavours of Fuji 67 Before & After 114-116 4K 68 Build Me a Home 16 Tropical Gourmet: Queensland We are showcasing a number of new and which includes more 69 Dream Home Ideas 17 Tropical Gourmet: New Caledonia 114 Million Dollar House Hunters original series through our joint-venture 70 The Home Team than 1200 hours 18-19 A Rosie Summer 115 Luxury Homes Revealed with Projucer, which sees the launch of 71 Best Gardens Australia 20-21 Tasty Conversations with 116 United Plates of America Jack Stein: Inside the Box, Life is Sweet of programming Audra Morrice: Aussie Road Trip and the much anticipated series Desert 22 Tasty Conversations with Vet, which premiers on Network Seven which can be seen Audra Morrice 74-89 Science & 117 Get in touch next month. -

Official Hansard

FIFTY-SECOND PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION OFFICIAL HANSARD WEDNESDAY 10 NOVEMBER 1999 Authorised by the Parliament of New South Wales 2503 LEGISLATIVECOUNCIL Wednesday 10 November 1999 ______ The President (The Hon. Dr Meredith (ii) not published or copied without an order of the Burgmann) took the chair at 11.00 a.m. House. The President offered the Prayers. 4. That in the event of a dispute by any member of the House communicated in writing to the Clerk as to the validity of a claim of legal professional privilege or public M2 PROJECT FINANCING interest immunity in relation to a particular document: Motion by the Hon. R. S. L. Jones agreed (a) the Clerk is authorised to release the disputed to: document to an independent legal arbiter who is either a Queen's Counsel, a Senior Counsel or a retired Supreme Court judge, appointed by the 1. That under Standing Order 18 and further to the order of President, for evaluation and report within five days the House of 21 October 1999, there be laid on the table as to the validity of the claim, and of the House by 5.00 p.m. Wednesday 18 November 1999 and made pubic without restricted access: (b) any report from the independent arbiter is to be tabled with the Clerk of the House, and: (a) the legal advice referred to in the undated letter from the Acting Chief Executive, Roads and Traffic (i) made available only to members of the Authority [RTA] to the Director-General, Premier's Legislative Council, and Department, relating to the M2 Motorway, lodged with the Clerk of the House on 28 October 1999, and any document which records or refers to the (ii) not published or copied without an order of the production of documents under the previous order of House. -

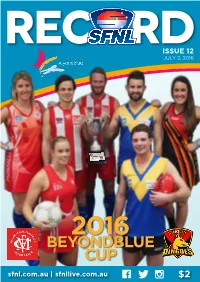

2016 SFNL Record – Issue 12

ISSUE 12 JULY 2, 2016 2016 BEYONDBLUE CUP www.sfnl.com.au | www.sfnllive.com.au #OWNTHESOUTH WHAT’S HAPPENING AT SFNL HQ? DAVID CANNIZZO, SFNL CEO @SFNLCEO beyondblue Round beyondblue’s 24/7 Support No. is 1300 22 4636 or online chat is beyondblue recognises the importance sport has in the Australian available 3pm-midnight at beyondblue.org.au/getsupport community. They have formed key partnerships with national and state elite sporting clubs and associations to be able to directly beyondblue will have a very strong presence at the marquee match engage with large and diverse communities. this weekend at Ben Kavanagh Reserve between Mordialloc and Dingley. Around the ground there will be representatives from 2015 was the first year of beyondblue’s partnership with the beyondblue sharing free resources and information along with Southern Football Netball League in which the inaugural SFNL collecting donations. beyondblue Round was held over the opening weekend of the 2015 Inside the club rooms will be the official beyondblue luncheon season. which has been fantastically supported by Mordialloc and Dingley, A special SFNL beyondblue Cup match was the highlight of the who we thank for their involvement in this wonderful initiative. We round. also appreciate Mordialloc being so accommodating in hosting the marquee game and luncheon which will feature special guest The SFNL are pleased to again partner with beyondblue this speaker, beyondblue Ambassador and former Geelong premiership year in an initiative that will see this weekend embraced as the player James Podsiadly. beyondblue Round. These two clubs will also be competing for the beyondblue Cup The community partnership is focused on raising awareness of which will be encompassing all competitions where the two clubs anxiety, depression and suicide prevention – and aims to provide are drawn to play each other over this weekend, to determine the support for those that may be experiencing a mental health winner. -

Engaging, Persuading, and Entertaining Citizens: Mediatization and the Australian Political Public Sphere

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Flew, Terry& Swift, Adam (2015) Engaging, persuading, and entertaining citizens: mediatization and the Australian political public sphere. International Journal of Press/Politics, 20(1), pp. 108-128. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/79440/ c Consult author(s) regarding copyright matters This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161214552500 International Journal of Press/Politics Engaging, Persuading and Entertaining Citizens: Mediatization and the Australian Political Public Sphere Journal:For The InternationalPeer Journal Review of Press/Politics Manuscript ID: RA-IJPP-Feb-2014-026.R2 Manuscript Type: Research Article Public sphere, Political participation, Television, Political advertising, Keywords: Television campaign, Broadcasting news This paper draws upon public sphere theories and the 'mediatization of politics' debate to develop a mapping of the Australian political public sphere, with particular reference to television. -

Graham Richardson

Graham Richardson Former ALP minister and political powerbroker Graham ‘Richo’ Richardson has a reputation as one of Australia’s foremost political operators and right-wing powerbrokers, despite having retired from politics in 1994. Graham Richardson joined the Australian Labor Party in 1966 when he was seventeen and soon apprenticed himself to the powerbrokers in the NSW Right, some of the toughest men in the Labor Party. So began a successful and colourful political career that took him from Labor Party branch organiser to General Secretary of the Australian Labor Party (NSW Branch), Senator for New South Wales for the ALP and a senior minister in the Hawke and Keating governments, making him one of the Labor Party’s key figures until his retirement. In his 11 years in federal politics, Graham held the ministerial portfolios of Environment, Arts, Sport, Tourism, Territories, Social Security, Transport, Communications and Health. Richo came to personify political ruthlessness and established the NSW Right of the Labor Party as a formidable political force on the national scene. He became famous for the line “whatever it takes” in reference to Labor doing “whatever it takes” to retain power. This also became the title of his best-selling account of career politics, published in 1994. Known as a king-maker, Graham Richardson had a significant influence on a great many political careers. He was instrumental in replacing Bill Hayden as federal leader with Bob Hawke in 1983 then Hawke with Paul Keating in 1991. After leaving politics in 1994, Richo spent eight years working for various parts of the Packer empire. -

Plane Crash Kills Pilot Health and Safety of Recovery Houses No One Disputes That Henry Green Kitchen, and Com- Provides a Valuable – Some Say Lifesaving Mon Area

■ Barnabas helps with Cares Act 5B ■ Crescendo Amelia 7B Inside This WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 23, 2020 / 22 PAGES, 2 SECTIONS • fbnewsleader.com $1.00 Issue City reviews the Plane crash kills pilot health and safety of recovery houses No one disputes that Henry Green kitchen, and com- provides a valuable – some say lifesaving mon area. They – service in Fernandina Beach. Places are required to for people who have nowhere else to go, attend the twice- due to the life they lived as addicts. But, daily Narcotics can Green legally operate a residential Anonymous and/ recovery facility in the city? That is the or Alcoholics question at the heart of what Fernandina Anonymous meet- Beach says are code enforcement viola- ings, to keep their tions at the houses used for Grace and living space clean, Gratitude Sober Living Inc. Green to get a job, and Green rents four houses in the keep the house city that he uses to operate Grace and clean. Gratitude. The houses are located on Food is not provided, but everyone Vernon Street, South 10th Street, South is encouraged to buy enough to cook Ninth Street, and South 13th Street. “family style” for everyone in the house. Grace and Gratitude receives no Those staying in the houses sign a con- local, state or federal funding; no grants tract before they are allowed to stay, or loans or other funding other than a and must adhere to the rules to stay. $21.50 daily fee from residents. Green They must, above all, stay alcohol- and said each house costs approximately drug-free. -

Download Our Winter 2003 Journal

U N I T E D PLANT SAVERS J o u r n a l o f M e d i c i n a l P l a n t C o n s e r v a t i o n W i n t e r 2 0 0 3 WELCOME LYNDA LEMOLE UpS’ new Executive Director DOING IT RIGHT Issues and practices of sustainable harvesting of non-timber forest products relating to First Peoples in British Columbia GREEN LOVER PROFILE Lorrie Otto THE MAGIC OF MUSHROOMS CULTIVATING GENTIAN ATAGA’HI Preserving Ancient Cherokee Burial Grounds UpS is a non-profit education corporation dedicated to preserving native medicinal plants. GREETINGS FROM UPS BE GRATEFUL For The SMALL MIRACLES Over the HOLIDAYS And throughout THE NEW YEAR It’s been a year ~ for UpS, for the world, for most people that I talk to ~ a year full of challenges and opportunities, changes and shifts. For UpS there’s certainly been an abundance of all of that ~ challenges, opportunities, changes and shifts. We had a major fire in the UpS office just a few months after moving it to Ohio and a new office has been built. We hired a Winter 2003 new office manager last year as Nancy Scarzello was ready to take on different tasks within the A publication of United Plant organization. She’s been focusing her energy on developing programs for children/schools and Savers, a non-profit education parents to teach the importance of our medicinal plant heritage and will have these children’s corporation dedicated to preserving programs ready to test ‘in the field’ this year. -

Season 2014 Record Volunteer Round

SEASON 2014 RECORD VOLUNTEER ROUND ROUND 18 SATURDAY 23 AUGUST VV VV VV VV VV PENINSULA FOOTBALL NETBALL LEAGUE This week... Office Talk The home and away season wraps Round 18 will feature three rivalry clashes to round up this weekend and it seems like the season off. Two of the Casey Cardinia League big only a couple of weeks ago we guns in Pakenham and Beaconsfield will engage in were assisting clubs get their teams and houses in a pre-finals face off for the Highway Cup. In Nepean order as the season began. It is always the same and, League two venues will see a little extra on the line on behalf of the 2014 PCNSA board of directors, all with southern Peninsula rivals Rye and Sorrento clubs are to be congratulated for their efforts both on playing for the Jennings Cup and Dromana and Red and off the sporting field this year. Hill lining up with the Bluey Holmes Shield on the While finals are firmly on the minds of those teams line. Good luck to all sides. involved, it is appropriate to acknowledge and say Next week we start another huge finals series at well done to those that are moth-balling their boots venues across our three leagues. Please check our and jumpers after the final siren this weekend. While websites or Facebook page for all the details and it is always a little disappointing for the players and get along and support your club in the quest for officials in that boat, there is always next season to glory. -

The Unwinding of Gonski Part 1: Abbott to Turnbull

SAVE OUR SCHOOLS The Unwinding of Gonski Part 1: Abbott to Turnbull Trevor Cobbold Working Paper April 2020 http://www.saveourschools.com.au https://twitter.com/SOSAust [email protected] 1 Preface This working paper attempts to provide a comprehensive review of the sabotage of the Gonski school funding model by the Abbott and Turnbull Governments. A second paper is planned on the completion of the sabotage under new funding arrangements introduced by the Turnbull and Morrison Governments. Another paper will review the funding model recommended by the Gonski report and its implementation under the Gillard and Rudd Labor Governments. Comments on this paper are invited. Notification of issues not covered and mistakes of fact, analysis and interpretation will be appreciated. Please excuse any remaining typos and repetitions. Comments can be sent to the Save Our Schools email address: [email protected] . 2 Table of Contents 1. Main features of the Labor Government’s school funding plan ................................................. 4 2. Coalition position before the 2013 election ............................................................................... 7 3. Abbott Government changes to Gonski ................................................................................... 12 3.1 The Abbott Government reneged on its unity ticket ......................................................... 12 3.2 The funding increase was limited to four years ................................................................. 14 3.3 -

18 March 2019

18TH JANUARY – 1ST FEBRUARY 2019 VOL 36 – ISSUE 02 Australia Day 2019— See page 2-5 for details — Sandstone MARK VINT MARK VINT Sales 9651 2182 Buy Direct From the Quarry WantingWanting to try to try something something new new in 2018? in 2019? 9651270 New Line2182 Road WhyWhy not not join join us at us Creative at Creative Activities Activities to learn a tonew learn (or old) a new craft and make a new friend or two. 270Dural New NSW Line 2158 Road (or old) craft and make a new friend or two. 9652 1783 Why not try “MakingNew class the—Sharpening Most of Your the Brain Media” or Tai Chi [email protected] NSW 2158 Your Total Trade Solution for Residential, Commercial & Industrial [email protected]: 84 451 806 754 Gabion Spalls $16.50/T (min) Wednesdays—9.30amWednesdays—9.30am to to 12.30pm 12.30pm ABN: 84 451 806 754 75mm - 150mm for baskets Plumbing • Electrical • Hot Water 86 86Cecil Cecil Avenue, Avenue, Castle Castle Hill Hill WWW.DURALAUTO.COM 0415 20 33 88 CommencingCommencing FebruaryFebruary 7,6, 2018 2019 WWW.DURALAUTO.COM 113 Smallwood Rd Glenorie enquiriesenquiries ~ ~9659 9659 0242 0242 or email:email: [email protected] [email protected] cracking and working dog each of our new citizens, demonstrations from Tobruk personally. AUSTRALIA Sheep Station. I’m also looking forward Australia Day is a time to meeting the recipients of for us to reflect on our our Australia Day Awards. nation’s strengths and These dedicated community identity, and on our own members continue to personal journey,” Mayor strive to create a beautiful, Byrne said.“It’s also a time welcoming and inclusive Community News Community DAY to celebrate everything that environment, and I look makes The Hills Shire a great forward to honouring them place to live, grow and raise on the day. -

Sky News 2018

MEDIA RELEASE: Monday October 30, 2017 SKY NEWS 2018 WORLD CLASS SKY NEWS BUSINESS CENTRE LAUNCHES CREATES DYNAMIC NEWS CORP AUSTRALIA NATIONAL BUSINESS HUB FURTHER INVESTMENT IN NATIONAL AFFAIRS PROGRAMS TOP RATING EVENING LINE-UP EXPANDED Sky News today revealed a turbocharged 2018 line-up across its suite of channels including the launch of a new world class business centre and television studio, an expanded evening schedule and further investment in national affairs programming. Marking its biggest single investment since launch in 1996, Sky News today unveiled a new broadcast and business centre based at News Corp HQ in Sydney’s centre, now home to Australia’s only 24-hour business channel Sky News Business. The state-of-the-art dedicated business studio will broadcast live, breaking business news across the country and sees the creation of the News Corp Australia National Business Hub. Michael Miller, Executive Chairman of News Corp Australasia said: “The move of Sky News Business to Holt Street is an exciting step for our company, with the channel now based at the centre of Australian business journalism. “The new studio creates, for the first time, a dynamic business hub delivering high value business news video content across all News Corp Australia platforms and brands.” Angelos Frangopoulos, Australian News Channel CEO said: “When News Corp Australia acquired the Sky News company last year, we began to closely integrate our businesses, our talent and our teams. Bringing Sky News Business into News Corp HQ not only reinforces our continued commitment to quality journalism, it brings new levels of vibrancy to our businesses and many collaborative opportunities in the future.” The Sky News Business finance experts including Ticky Fullerton, Carson Scott, Ingrid Willinge, James Daggar-Nickson, Helen Dalley, Leanne Jones, Natalie MacDonald and Leo Shanahan will broadcast from the new studio covering the latest breaking business, finance and market news. -

'Richo' Richardson Returns to Wednesday Nights Peta

MEDIA RELEASE: Tuesday May 23, 2017 GRAHAM ‘RICHO’ RICHARDSON RETURNS TO WEDNESDAY NIGHTS PETA CREDLIN JOINS ALAN JONES FOR JONES & CO Graham Richardson will make a bold return to SKY NEWS LIVE’s Wednesday primetime line-up following his recovery from surgery. From this week, Richo will return home to Wednesdays at 8:00pm as Australia’s ultimate political insider brings his unique insights into a range of the day’s topics, not just politics. Angelos Frangopoulos, Australian News Channel CEO said: “Richo has been working his way back to a full on-air workload since undergoing life-saving surgery more than a year ago. He is an outstanding commentator and we’re delighted to see him back on Wednesday nights.” Richo’s return to Wednesday nights will see a number of changes to the primetime schedule. Peta Credlin joins Alan Jones as co-host on Jones & Co, Tuesdays at 8:00pm. Two of Australia’s most prominent and influential commentators, Alan and Peta will bring viewers powerful analysis, lively discussion and guests from across the political spectrum. SKY NEWS also confirmed planning is underway for a new program to be anchored by Peta Credlin, with further details to be announced later in 2017. With Richo’s return to Wednesday nights, Credlin Keneally goes into recess as Kristina Keneally steps up to a bigger role on SKY NEWS daytime, anchoring LIVE coverage from Canberra during sitting weeks alongside Peter van Onselen. Former Queensland Premier Campbell Newman will join Peter Beattie each week on Beattie & Reith, Mondays at 8:00pm while Peter Reith continues his recovery.