Engaging, Persuading, and Entertaining Citizens: Mediatization and the Australian Political Public Sphere

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sexiest Politicians Get Vote | Herald Sun Page 1 of 2

Sexiest politicians get vote | Herald Sun Page 1 of 2 Sexiest politicians get vote Ben Packham December 08, 2006 12:00am Article from: OUR best-looking politician is not even in Parliament ¿ and John Howard can thank his lucky stars for that. Nicole Campbell, who stood against the Prime Minister, was rated the most attractive candidate at the 2004 election. The Australian National University rated politicians using how-to-vote cards. It wasn't good news for Mr Howard – or Labor leader Kevin Rudd. Proving looks aren't everything, the PM came in 279 out of 286. Mr Rudd did marginally better at 244. But Julie Bishop can take a bow. She has the beauty to match her brainy portfolio. The Education Minister was the most attractive sitting female MP, at fifth overall. Victoria's best looker was newly crowned deputy Labor leader Julia Gillard at No. 12. Rising Liberal star Malcolm Turnbull ran a dapper 18th. Leadership rival Peter Costello (169) has plenty of ground to make up. He wouldn't even beat Kim Beazley (152) in a beauty contest. Health Minister Tony Abbott was rated not too shabby at 96 and Workplace Relations Minister Kevin Andrews was a respectable 114. Labor childcare spokeswoman Tanya Plibersek was looking good at 21, while Victoria's best- looking bloke was Flinders Lib MP Greg Hunt (55). Other highly rated Victorians included Labor member for Ballarat Catherine King (24), and member for Indi Sophie Mirabella (29). ANU's Andrew Leigh, who conducted the study, did not reveal who ran last because it would be unfair. -

First Century Fox Inc and Sky Plc; European Intervention Notice

Rt Hon Karen Bradley Secretary of State for Digital Culture Media and Sport July 14 2017 Dear Secretary of State Twenty-First Century Fox Inc and Sky plc; European Intervention Notice The Campaign for Press and Broadcasting is responding to your request for new submissions on the test of commitment to broadcasting standards. We are pleased to submit this short supplement to the submission we provided for Ofcom in March. As requested, the information is up-to-date, but we are adding an appeal to you to reconsider Ofcom’s recommendation to accept the 21CF bid on this ground, which we find wholly unconvincing in the light of the evidence we submitted. SKY NEWS IN AUSTRALIA In a pre-echo of the current buyout bid in the UK, Sky News Australia, previously jointly- owned with other media owners, became wholly owned by the Murdochs on December 1 last year. When the CPBF made its submission on the Commitment to Broadcasting Standards EIN to Ofcom in March there were three months of operation by which to judge the direction of the channel, but now there are three months more. A number of commentaries have been published. The Murdoch entity that controls Sky Australia is News Corporation rather than 21FC but the service is clearly following the Fox formula about which the CPBF commented to Ofcom. Indeed it is taking the model of broadcasting high-octane right-wing political commentary in peak viewing times even further. While Fox News has three continuous hours of talk shows on weekday evenings, Sky News Australia has five. -

Australian 2013 Election: the Tribe Has Spoken

Australian 2013 Election: The tribe has spoken Economic research note 9 September 2013 As widely expected, the Liberal/National Coalition has Australian election: The tribe has spoken easily won the Australian Federal election held over the Australians went to the polls over the weekend, voting on a weekend. full House of Representatives (150 seats) and a half Senate (76 The Coalition increased their seats in the Lower House seat) election. from 72 to a projected 89, easily giving them a strong majority. As widely expected ahead of the election and as signalled by a number of opinion polls, the election has resulted in a change In contrast, the number of seats held by the ALP dropped of government. to an estimated 57 from 71. The Liberal/National party coalition, led by new Prime Minister However, the new Senate, which does not sit until 1 July Tony Abbott has defeated the incumbent Australian Labor 2014, could be problematic for the Coalition, as there Party (ALP) minority government, led by Kevin Rudd. could be up to 8 Senators from smaller parties/Independents and up to 10 Greens. With swing of 4.1% away from the ALP, some of which went to smaller parties and Independents, the Coalition now looks With the Coalition likely to have 33 Senators, they will 1 need to secure the vote of 6 of the smaller party like they will hold 89 seats in the House of Representatives , Senators (or the ALP) to pass legislation. well up from their previous number of 72. This gives the Coalition a comfortable majority of 13 in the House (i.e. -

Parade-RGB.Pdf

CONTENTS WELCOME This year, we are proud to present a 06-33 Food & Travel 58-71 Home & Garden 108-111 Format fantastic and diverse line-up of new and We are delighted returning content that we will launch to 06-07 Inside the Box with Jack Stein our buyers at MIPCOM 2017. to welcome you to 58-59 Million Dollar House Hunters 108-109 Restaurant Revolution 08 Andy & Ben Eat Australia 60-61 Luxury Homes Revealed 110-111 Greatest Chefs Parade’s MIPCOM For this market we are bringing 160 hours 09 Andy & Ben Eat the World 62-63 Ready Set Reno of new content which includes a brand 10-11 Sara’s Australia Unveiled 64-65 Find Me a Home in the Country 2017 portfolio of hit new and exciting line-up of lifestyle and 12-13 United Plates of America 66 Australia’s Best Houses factual series being launched. series and originals 14-15 Justine’s Flavours of Fuji 67 Before & After 114-116 4K 68 Build Me a Home 16 Tropical Gourmet: Queensland We are showcasing a number of new and which includes more 69 Dream Home Ideas 17 Tropical Gourmet: New Caledonia 114 Million Dollar House Hunters original series through our joint-venture 70 The Home Team than 1200 hours 18-19 A Rosie Summer 115 Luxury Homes Revealed with Projucer, which sees the launch of 71 Best Gardens Australia 20-21 Tasty Conversations with 116 United Plates of America Jack Stein: Inside the Box, Life is Sweet of programming Audra Morrice: Aussie Road Trip and the much anticipated series Desert 22 Tasty Conversations with Vet, which premiers on Network Seven which can be seen Audra Morrice 74-89 Science & 117 Get in touch next month. -

Al Jazeera's Expansion: News Media Moments and Growth in Australia

Al Jazeera’s Expansion: News Media Moments and Growth in Australia PhD thesis by publication, 2017 Scott Bridges Institute of Governance and Policy Analysis University of Canberra ABSTRACT Al Jazeera was launched in 1996 by the government of Qatar as a small terrestrial news channel. In 2016 it is a global media company broadcasting news, sport and entertainment around the world in multiple languages. Devised as an outward- looking news organisation by the small nation’s then new emir, Al Jazeera was, and is, a key part of a larger soft diplomatic and brand-building project — through Al Jazeera, Qatar projects a liberal face to the world and exerts influence in regional and global affairs. Expansion is central to Al Jazeera’s mission as its soft diplomatic goals are only achieved through its audience being put to work on behalf of the state benefactor, much as a commercial broadcaster’s profit is achieved through its audience being put to work on behalf of advertisers. This thesis focuses on Al Jazeera English’s non-conventional expansion into the Australian market, helped along as it was by the channel’s turning point coverage of the 2011 Egyptian protests. This so-called “moment” attracted critical and popular acclaim for the network, especially in markets where there was still widespread suspicion about the Arab network, and it coincided with Al Jazeera’s signing of reciprocal broadcast agreements with the Australian public broadcasters. Through these deals, Al Jazeera has experienced the most success with building a broadcast audience in Australia. After unpacking Al Jazeera English’s Egyptian Revolution “moment”, and problematising the concept, this thesis seeks to formulate a theoretical framework for a news media turning point. -

Tweeting to Save the Furniture: the 2013 Australian Election Campaign on Twitter

Tweeting to Save the Furniture: The 2013 Australian Election Campaign on Twitter Introduction Past years have seen continuing experimentation around the world in the use of online publishing and engagement technologies for political campaigning (Bruns et al., 2016). Australia, with its exceptionally short legislative periods of (nominally) three years at federal level, provides a particularly useful environment in which the transition towards increased online campaigning can be observed. This also traces the changing mix amongst the digital platforms: the online campaign of the 2007 federal election was overshadowed by the “blog wars” between conservative and progressive commentators over the correct interpretation of opinion poll results (Jericho, 2012; Bruns & Highfield, 2012), and the major parties also experimented with online videos posted to YouTube, with varying success (Bruns et al., 2007), but Facebook and Twitter did not yet feature in any significant way. By 2010, blog-style columns had been incorporated into mainstream online news platforms from The Australian to Crikey, and no longer played a distinct role in the campaign. Instead, following the widespread adoption of Facebook and (less strongly so) Twitter, and the role that such tools played in covering the Rudd/Gillard leadership spill earlier in the year (Posetti, 2010; Bruns & Burgess, 2015), parties, candidates, journalists, and commentators began to incorporate social media more fully into their campaigning activities (cf. Grant et al., 2010). However, in spite of the significant journalistic and scholarly attention paid to these developments, the still distinctively netizen- dominated userbase demographics of a platform such as Twitter also resulted in social media debates about the election that focussed largely on technology topics such as the proposed National Broadband Network and Internet filter. -

EUREKA Country Mile! Garages & Sheds Farming and Industrial Structures

The Moorabool News FREE Your Local News Tuesday 5 November, 2013 Serving Ballan and district since 1872 Phone 5368 1966 Fax 5368 2764 Vol 7 No 43 He’s our man! By Kate Taylor Central Ward Councillor Paul Tatchell has been voted as Moorabool’s new Mayor. East Ward Councillor John Spain was voted in as Deputy Mayor. Outgoing Mayor Pat Toohey did not re-nominate at the Statutory and Annual Appointments Meeting held last Wednesday 30 October, where Mayor Tatchell won the role with a 5-2 majority. Nominated by East Ward Councillor Allan Comrie, Cr Tatchell gained votes from fellow councillors Comrie, David Edwards, Tonia Dudzik and John Spain. West Ward Councillor Tom Sullivan was nominated and voted for by Pat Toohey. New Mayor Tatchell told the meeting he was very fortunate to have been given the privilege of the role. “For former mayor Pat Toohey, to have come on board and then taken on the role of Mayor with four new councillors, he jumped straight in the driver’s seat… and the first few months were very difficult, but he persevered with extreme patience. “And to the experienced councillors we came in contact with from day one, with years of experience, without that, I can’t imagine how a council could have operated with seven new faces. We are incredibly fortunate to have those experienced councillors on board.” Mayor Tatchell also hinted at a vision for more unity in the future. “A bit less of ‘I’ and more of ‘we,’” he said. Deputy Mayor Spain was voted in with votes from councillors Dudzik, Edwards, and Comrie, with Mayor Tatchell not required to cast a vote on a majority decision. -

Official Hansard

FIFTY-SECOND PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION OFFICIAL HANSARD WEDNESDAY 10 NOVEMBER 1999 Authorised by the Parliament of New South Wales 2503 LEGISLATIVECOUNCIL Wednesday 10 November 1999 ______ The President (The Hon. Dr Meredith (ii) not published or copied without an order of the Burgmann) took the chair at 11.00 a.m. House. The President offered the Prayers. 4. That in the event of a dispute by any member of the House communicated in writing to the Clerk as to the validity of a claim of legal professional privilege or public M2 PROJECT FINANCING interest immunity in relation to a particular document: Motion by the Hon. R. S. L. Jones agreed (a) the Clerk is authorised to release the disputed to: document to an independent legal arbiter who is either a Queen's Counsel, a Senior Counsel or a retired Supreme Court judge, appointed by the 1. That under Standing Order 18 and further to the order of President, for evaluation and report within five days the House of 21 October 1999, there be laid on the table as to the validity of the claim, and of the House by 5.00 p.m. Wednesday 18 November 1999 and made pubic without restricted access: (b) any report from the independent arbiter is to be tabled with the Clerk of the House, and: (a) the legal advice referred to in the undated letter from the Acting Chief Executive, Roads and Traffic (i) made available only to members of the Authority [RTA] to the Director-General, Premier's Legislative Council, and Department, relating to the M2 Motorway, lodged with the Clerk of the House on 28 October 1999, and any document which records or refers to the (ii) not published or copied without an order of the production of documents under the previous order of House. -

Sceptical Climate Part 2: CLIMATE SCIENCE in AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPERS

October 2013 Sceptical Climate Part 2: CLIMATE SCIENCE IN AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPERS Professor Wendy Bacon Australian Centre for Independent Journalism Sceptical Climate Part 2: Climate Science in Australian Newspapers ISBN: 978-0-9870682-4-8 Release date: 30th October 2013 REPORT AUTHOR & DIRECTOR OF PROJECT: Professor Wendy Bacon (Australian Centre for Independent Journalism, University of Technology, Sydney) PROJECT MANAGER & RESEARCH SUPERVISOR: Arunn Jegan (Australian Centre for Independent Journalism) PROJECT & RESEARCH ADVISOR: Professor Chris Nash (Monash University) DESIGN AND WEB DEVELOPMENT Collagraph (http://collagraph.com.au) RESEARCHERS: Nicole Gooch, Katherine Cuttriss, Matthew Johnson, Rachel Sibley, Katerina Lebedev, Joel Rosenveig Holland, Federica Gasparini, Sophia Adams, Marcus Synott, Julia Wylie, Simon Phan & Emma Bacon ACIJ DIRECTOR: Associate Professor Tom Morton (Australian Centre for Independent Journalism, University of Technology, Sydney) ACIJ MANAGER: Jan McClelland (Australian Centre for Independent Journalism) THE AUSTRALIAN CENTRE FOR INDEPENDENT JOURNALISM The Sceptical Climate Report is a project by The Australian Centre for Independent Journalism, a critical voice on media politics, media policy, and the practice and theory of journalism. Follow ACIJ investigations, news and events at Investigate.org.au. This report is available for your use under a creative commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0) license, unless specifically noted. Feel free to quote, republish, backup, and move it to whatever platform works for you. Cover graphic: Global Annual Mean Surface Air Temperature Change, 1880 - 2012. Source: NASA GISS 2 Table of Contents 1. Preface . 5 2. Key Findings. 10 3. Background Issues . 28 4. Findings 4.1 Research design and methodology. 41 4.2 Quantity of climate science coverage . -

0827 LLS Web.Pdf

PRSRT STD ECRWSS U.S. Postage Paid Permit #017 ZIP CODE 99019 SEPTEMBER 2014 FULL CIRCLE BARLOWS CV TEAMS FOR NEW GES MURAL TRACES PREPPING FOR PRINCIPAL LL HISTORY FALL SUCCESS PAGE 14 PAGE 31 PAGE 34 2 • SEPTEMBER 2014 NEWS The Splash Taking stock in A Cup of Joe the Market Parker was born and raised in the Spo- kane area, graduating from Gonzaga Prep Parker has served integral in 1990. She earned her degree from East- role with LL Farmers ern Washington University and taught for two years in Nevada before moving back Market since 2002 to the Inland Northwest in 2002. She has called Liberty Lake home since then, a By Craig Howard place she describes as “a great community SPLASH CONTRIBUTOR to be a part of.” In addition to the market, When it began in 2002, the Liberty Lake her calendar is consistently full of outdoor Farmers Market featured a humble collec- events, particularly the movies and con- certs in Pavillion Park each summer. tion of vendors gathered in a cheerful space SPLASH PHOTO BY CRAIG HOWARD along Meadowwood Lane. Holli Parker has been with the Liberty Lake Farmers Market since it started in 2002. The In her second stint as market manager, Parker is responsible for an array of duties, Holli Parker served as the venue’s manag- Spokane native and Liberty Lake resident currently serves as the market manager. including map/vendor layout and logis- er in those fledgling years, coordinating the tics, answering emails, event coordination lineup and schedule each Saturday while The idea for the outdoor galleria sprang civic identity. -

Transcript of Q&A Session Following Malcolm Turnbull's Address to The

Transcript of Q&A session following Malcolm Turnbull’s address to the 2013 Kickstart Forum 19 Feb 2013 JOURNALIST: What’s the future of publicly funded research organisations like NICTA and the CSIRO look like under a Coalition Government? MALCOLM TURNBULL: Good. We are very supportive of all those institutions. They were all around and supported by the Coalition when we were last in Government. JOURNALIST: So you will continue to fund them? MALCOLM TURNBULL: Well we will certainly continue to fund them. I can’t give you a commitment to a particular dollar amount because that’s something that we will announce in the lead up to the election. But the Coalition’s track record in supporting and establishing a number of these organisations over the years speaks for itself. JOURNALIST: So just in terms of your innovation policy and given we know the election date beforehand roughly when would you be releasing that? MALCOLM TURNBULL: Well you would really – that’s really a matter for Sophie Mirabella who’s got the ministerial responsibility for this area. And that will be done between now and the election. NICK ROSS, ABC: What’s broadband for? What’s its main benefits in your view? MALCOLM TURNBULL: Well it’s for everything, isn’t it? It’s for everything – you know – NICK ROSS, ABC: Can you give us some specifics? MALCOLM TURNBULL: Well I’m not quite sure what the purpose of your question is. Broadband is used for every form of communication, entertainment, commerce – it’s a technology that is limited only by our imagination. -

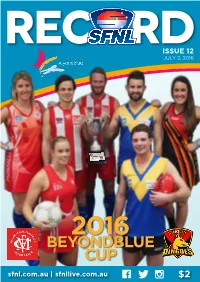

2016 SFNL Record – Issue 12

ISSUE 12 JULY 2, 2016 2016 BEYONDBLUE CUP www.sfnl.com.au | www.sfnllive.com.au #OWNTHESOUTH WHAT’S HAPPENING AT SFNL HQ? DAVID CANNIZZO, SFNL CEO @SFNLCEO beyondblue Round beyondblue’s 24/7 Support No. is 1300 22 4636 or online chat is beyondblue recognises the importance sport has in the Australian available 3pm-midnight at beyondblue.org.au/getsupport community. They have formed key partnerships with national and state elite sporting clubs and associations to be able to directly beyondblue will have a very strong presence at the marquee match engage with large and diverse communities. this weekend at Ben Kavanagh Reserve between Mordialloc and Dingley. Around the ground there will be representatives from 2015 was the first year of beyondblue’s partnership with the beyondblue sharing free resources and information along with Southern Football Netball League in which the inaugural SFNL collecting donations. beyondblue Round was held over the opening weekend of the 2015 Inside the club rooms will be the official beyondblue luncheon season. which has been fantastically supported by Mordialloc and Dingley, A special SFNL beyondblue Cup match was the highlight of the who we thank for their involvement in this wonderful initiative. We round. also appreciate Mordialloc being so accommodating in hosting the marquee game and luncheon which will feature special guest The SFNL are pleased to again partner with beyondblue this speaker, beyondblue Ambassador and former Geelong premiership year in an initiative that will see this weekend embraced as the player James Podsiadly. beyondblue Round. These two clubs will also be competing for the beyondblue Cup The community partnership is focused on raising awareness of which will be encompassing all competitions where the two clubs anxiety, depression and suicide prevention – and aims to provide are drawn to play each other over this weekend, to determine the support for those that may be experiencing a mental health winner.