The Bigness Mystique and the Merger Policy Debate: an International Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How British Leyland Grew Itself to Death by Geoff Wheatley British Car Network

How British Leyland Grew Itself To Death By Geoff Wheatley British Car Network I have always wondered how a British motor company that made trucks and other commercial vehicles, ever got its hands on Jaguar, Triumph, and of course MG. Furthermore, how this successful commercial company managed to lose the goodwill and loyal customers of these popular vehicles. The story starts some fifteen years before British Leyland became part of the domestic vehicle market in the UK, and of course overseas, especially for Jaguar, a top international brand name in the post war years. In the early 1950s the idea of Group Industries was the flavor of the month. Any company worth its salt was ready to join forces with a willing competitor, or several competitors to form a “Commercial Group”. In consequence we had the Textile Groups, International Banking Groups, The British Nylon Group, Shell and BP Group etc. The theory was simple, by forming production groups producing similar products and exchanging both marketing and production techniques, costs would be reduced and sales would increase. The British Government, who had an investment in the British Motor Industry to help the growth of exports to earn needed US Dollars, was very much in favor of the Group Policy being applied to the major production companies in the UK including the Nuffield Organization and Austin Corporation. Smaller companies like Jaguar who were also successful exporters were encouraged to take the same view on production and sales, however they did not jump on the “Group” bandwagon and remained independent for a few more years. -

British V8 Newsletter (Aka MG V8 Newsletter)

California Dreaming: an MGB-GT-V8 on Route 66 (owners: Robert and Susan Milner) The British V8 Newsletter - Current Issue - Table of Contents British V8 Newsletter May - September 2007 (Volume 15, Issue 2) 301 pages, 712 photos Main Editorial Section (including this table of contents) 45 pages, 76 photos In the Driver's Seat by Curtis Jacobson Canadian Corner by Martyn Harvey How-to: Under-Hood Eaton M90 Supercharger on an MGB-V8! by Bill Jacobson How-to: Select a Performance Muffler by Larry Shimp How-to: Identify a Particular Borg-Warner T5 Transmission research by David Gable How-to: Easily Increase an MGB's Traction for Quicker Launches by Bill Guzman Announcing the Winners - First Annual British V8 Photo Contest by Robert Milks Please Support Our Sponsors! by Curtis Jacobson Special Abingdon Vacation Section: 51 pages, 115 photos Abingdon For MG Enthusiasts by Curtis Jacobson A Visit to British Motor Heritage (to see actual MG production practices!) by Curtis Jacobson The Building of an MG Midget Body by S. Clark & B. Mohan BMH's Exciting New Competition Bodyshell Program by Curtis Jacobson How BMH Built a Brand-New Vintage Race Car by Curtis Jacobson Special Coverage of British V8 2007: 67 pages, 147 photos British V8 2007 Meet Overview by Curtis Jacobson British V8 Track Day at Nelson Ledges Road Course by Max Fulton Measuring Up: Autocrossing and Weighing the Cars by Curtis Jacobson Valve Cover Race Results by Charles Kettering Continuing Education and Seminar Program Tech Session 1 - Digital Photography for Car People (with Mary -

Your Reference

MINI United Kingdom Corporate Communications Media Information 28 March 2013 STRICT EMBARGO 28.03.2013 00:01 GMT MINI PLANT LEADS CELEBRATION OF 100 YEARS OF CAR- MAKING IN OXFORD Transport Secretary opens centenary exhibition in new Visitor Centre and views multi-million pound investment for next generation MINI Today a centenary exhibition was opened in the new Visitor Centre at MINI Plant Oxford by Transport Secretary Patrick McLoughlin and Harald Krueger, Member of the Board of Management of BMW AG, to mark this major industrial milestone. One hundred years ago to the day, the first ‘Bullnose’ Morris Oxford was built by William Morris just a few hundred metres from where the modern MINI plant stands. With a weekly production of just 20 vehicles in 1913, the business grew rapidly and over the century 11.65 million cars were produced, bearing 13 different British brands and one Japanese. Almost 500, 000 people have worked at the plant in the past 100 years and in the early 1960s numbers peaked at 28,000. Today, Plant Oxford employs 3,700 associates who manufacture up to 900 MINIs every day. Congratulating the plant on its historic milestone, Prime Minister David Cameron said: "The Government is working closely with the automotive industry so that it continues to compete and thrive in the global race and the success of MINI around the world stands as a fine example of British BMW Group Company Postal Address manufacturing at its best. The substantial contribution which the Oxford plant BMW (UK) Ltd. Ellesfield Avenue Bracknell Berks RG12 8TA Telephone 01344 480320 Fax 01344 480306 Internet www.bmw.co.uk 0 MINI United Kingdom Corporate Communications Media Information Date 28 March 2013 MINI PLANT LEADS CELEBRATION OF 100 YEARS OF CAR-MAKING IN Subject OXFORD Page 2 has made to the local area and the British economy over the last 100 years is something we should be proud of." Over the years an array of famous cars were produced including the Morris Minor, the Mini, the Morris Marina, the Princess, the Austin Maestro and today’s MINI. -

02 FEB 2016 BSCC NEWS LETTER NF Com.Pdf

Next 2016 CALENDAR NOTES: - BSCC Meeting, at Roster’s, Park 5/3rd Bank Parking side Lot. Feb 18 Thursday 6:30 – 8:30 p.m. Rooster’s Shelbyville Rd in Middletown. Located: - junction of Moser Road and Shelbyville Road. 10430 Shelbyville Rd Suite 7, Louisville, KY 40233 Tel: (502) 883-1990 Feb 19-21 Fri - Sun Carl Casper Auto Show - BSCC to participate to show six cars to recruit new members.. Venue: Kentucky Fair & Expo Center, Louisville (1) Lotus Europa, Gary Rumrill: (2) Morgan, Peter Dakin (3) MG-B, Greg Bowman: (4) MG-Midget, Danny + Sylvia Jones (5) Triumph TR-6 or Spitfire Russell Mills: (6) Triumph TR-7, Leo Halbleib Mar 12 Saturday Kyana Swap Meet /Auction - 1000+ vendors, mostly American car parts Venue: Kentucky Fair & Expo Center, Louisville Mar 12 Saturday The St. Patrick’s Parade "100 Years Irish Rising" The Parade will be held As many as 150 units are expected again for this year’s parade that will step-off at 3 p.m. at Baxter and Broadway proceeding along the Baxter/Bardstown Road corridor. Often called the “people’s” parade, families join a mix of decorated vehicles and groups along the route. As many as 100,000+ people watched or marched in last year’s parade. Mar 19 Saturday Water by the Bridge at Festival Plaza, Waterfront Park Louisville, KY. Web site: - http://www. http://waterbythebridge.com/ Apr 16 Saturday The Euro District is a Midwest European car show. Venue: Big Four Station 4 Bridge St, Jeffersonville, Indiana 47130 Apr 16 Saturday BSCC 3rd Annual Swap Meet - Unique Automotive Venue: 3918 Bardstown Rd, #3, Louisville KY 40218 Tel: 502-452-2688 May 28 Saturday 14th Annual Mission Driven Car Show, St Francis In the Fields Episcopal Church 6710 Wolf Pen Branch Rd, Louisville, KY 40027 June 13-17 Mon-Fri MG-2016 – 5th North American National MG Register “A Run for the Roses”, Venue: Rally at Festival Plaza, Louisville, 1,000+ attendees. -

British Motor Corporation and Leyland Motor Corporation Photographs, 1963-1970. Archival Collection 104

British Motor Corporation and Leyland Motor Corporation photographs, 1963-1970. Archival Collection 104 British Motor Corporation and Leyland Motor Corporation photographs, 1963-1970. Archival Collection 104 Revs Institute Page 1 of 3 British Motor Corporation and Leyland Motor Corporation photographs, 1963-1970. Archival Collection 104 Title: British Motor Corporation and Leyland Motor Corporation photographs, 1963-1970. Creator: Camisasca, Henry P. Call Number: Archival Collection 104 Quantity: 1 linear foot (1 clamshell binder) Abstract: The British Motor Corporation and Leyland Motor Corporation photographs, 1963- 1970 consist of 713 color image slides from the 12 Hours of Sebring at the Sebring International Raceway. Language: Materials are in English. Biography: British Motor Corporation was a UK based vehicle manufacturer founded in 1952. Some car models included the Austin, MG, Morris, Riley, and Wolseley. In 1966, BMC merged with Jaguar Cars Limited and Pressed Steel to become British Motor Holdings Limited (BMH). Leyland Motor Corporation was a British vehicle manufacturer founded in 1896 that began by producing lorries, buses, and trolleybuses. They were involved in tank production during WWII, creating the Cromwell Tank. In 1968 British Motor Holdings and Leyland Motor Corporation merged to become British Leyland after being nationalized. British Leyland faced financial difficulties in 1974 and the main surviving organizations are Mini and Jaguar Land Rover. Acquisition Note: Accession number: 2019-004 Access Restrictions: The British Motor Corporation and Leyland Motor Corporation photographs, 1963-1970 are open for research. Publication Rights: Copyright has been assigned to the Revs Institute. Although copyright was transferred by the donor, copyright in some items in the collection may still be held by their respective creator. -

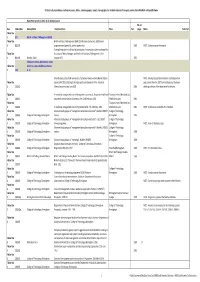

David Bramley Collection - ABS\David Bramley Collection.Xlsx Folder Box Factory Management Course

Collection of presentations, conference papers, letters, company papers, reports, monographs et.al. Includes materials from peers such as Frank Woollard and Lyndall Urwick. David Bramley (19.11.1913 - 31.07.2010) Collection No. of Box Folder/box Author/Editor Title/Description Place Year pages Notes Published Folder Box 1 B2.1 British Institute of Management (BIM) Folder Box British Institute of Management (BIM) 15th National Conference 1960. Dinner 1 B2.1.F1 programme and guests list, section papers et.al. 1960 NOTE: Contains course information. Getting things done in a climate of participation. Presented to a joint meeting of the Folder Box Institution of Works Managers and the British Institute of Management. 23rd 1 B2.1.F1 Bramley, David January 1975. 1975 College prospectus, programme, report, Folder Box brochures, course booklets, invitation 1 C3.1 et. al. Aston Business School 60th anniversary: Testimonial from an alumni Bernard Aston NOTE: Includes copy of Bernard Aston's cerificate and a 4 Folder Box (years 1944-1955) attesting to the high quality and standards of the Industrial page extract from the 1957 Guild of Associates Yearbook 1 C3.1.F1 Administration courses. June 2008. 2008 detailing activities of the department for the year. Folder Box A residential management course. Management course no. 4. Programme leaflet and Training Centre of Birchfield Ltd., 1 C3.1.F1 associated communication documents. 19th -24th February, 1961. Stratford-on-Avon. 1961 Folder Box Training Centre of Birchfield Ltd., 1 C3.1.F1 A residential management course. Programme leaflet. 7th -12th May, 1961. Stratford-on-Avon. 1961 NOTE: certificates presented by F. -

Your Reference

MINI United Kingdom Corporate Communications Media Information 8 March 2013 A CENTURY OF CAR-MAKING IN OXFORD Plant’s first car was a Bullnose Morris Oxford, produced on 28 March 1913 Total car production to date stands at 11,655,000 and counting Over 2,250,000 new MINIs built so far, plus 600,000 classic Minis manufactured at Plant Oxford Scores of models under 14 car brands have been produced at the plant Grew to 28,000 employees in the 1960s As well as cars, produced iron lungs, Tiger Moth aircraft, parachutes, gliders and jerry cans, besides completing 80,000 repairs on Spitfires and Hurricanes Principle part of BMW Group £750m investment for the next generation MINI will be spent on new facilities at Oxford The MINI Plant will lead the celebrations of a centenary of car-making in Oxford, on 28 March 2013 – 100 years to the day when the first “Bullnose” Morris Oxford was built by William Morris, a few hundred metres from where the modern plant stands today. Twenty cars were built each week at the start, but the business grew rapidly and over the century 11.65 million cars were produced. Today, Plant Oxford employs 3,700 associates who manufacture up to 900 MINIs every day, and has contributed over 2.25 million MINIs to the total tally. Major investment is currently under way at the plant to create new facilities for the next generation MINI. BMW Group Company Postal Address BMW (UK) Ltd. Ellesfield Avenue Bracknell Berks RG12 8TA Telephone 01344 480320 Fax 01344 480306 Internet www.bmw.co.uk 0 MINI United Kingdom Corporate Communications Media Information Date Subject A CENTURY OF CAR-MAKING IN OXFORD Page 2 Over the decades that followed the emergence of the Bullnose Morris Oxford in 1913, came cars from a wide range of famous British brands – and one Japanese - including MG, Wolseley, Riley, Austin, Austin Healey, Mini, Vanden Plas, Princess, Triumph, Rover, Sterling and Honda, besides founding marque Morris - and MINI. -

Morris Garages Ltd, Then Morris Motors

Official name: Morris Garages Ltd, then Morris Motors, then The Nuffield Organisation, then British Motor Corporation, then British Motor Holdings, Leyland Motor Corporation, British Leyland Motor Corporation, British Leyland Limited, Austin Rover Group, then Rover Group, then MG Rover. The company went bankrupt in 2005. Owned by: Shanghai Automotive Industry Corporation. Current situation: MGs are now built in China, with a few assembled at the old MG factory in England. However, many car designs are very old and all are poorly built. MG has not been a a big hit in China and sales outside China have been dreadful. Chances of survival: poor. SAIC is staying alive thanks to Chinese government handouts and joint ventures with Western companies. If MG’s new owners are relying on Western sales to prosper, they are probably in for a lonely old age • 1 All content © The Dog & Lemon Guide 2016 • All rights reserved A brief history of MG (and why things went so badly wrong) WAS ORIGINALLY an abbreviation MGof Morris Garages. Founded in 1924 by William Morris, MG sportscars were based on the basic structure of Morris’s other cars from that era. MGs soon developed a reputation for being fast and nimble. Sales boomed. Originally owned personally by William Morris, MG was sold in 1935 to the Morris parent company. This put MG on a sound financial footing, but also made MG a tiny subsiduary of a major corporation. Uncredited images are believed to be in the public domain. Credited images are copyright their respective 2 All content © The Dog & Lemon Guide 2016 • All rights reserved owners. -

We Are Very Pleased at the Prospect of Jaguar and Land Rover Being a Significant Part of Our Automotive Business

BSTR/313 IBS Center for Management Research Tata Motors’ Acquisition of Jaguar and Land Rover This case was written by Indu P., under the direction of Vivek Gupta, IBS Center for Management Research. It was compiled from published sources, and is intended to be used as a basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of a management situation. This case won the second runner up prize in the John Molson Case Writing Competition 2008, organized by the John Molson School of Business, Concordia University, Montreal, Canada. 2009, IBS Center for Management Research. All rights reserved. To order copies, call +91-08417-236667/68 or write to IBS Center for Management Research (ICMR), IFHE Campus, Donthanapally, Sankarapally Road, Hyderabad 501 504, Andhra Pradesh, India or email: [email protected] www.icmrindia.org BSTR/313 Tata Motors’ Acquisition of Jaguar and Land Rover “Acquisition of JLR provides the company with a strategic opportunity to acquire iconic brands with a great heritage and global presence, and increase the company’s business diversity across markets and product segments.”1 - Tata Motors, in April 2008. ―If they run the brands as a British company and invest properly in new product, it will be successful because they are still attractive brands.‖ 2 - Charles Hughes3, Founder, Brand Rules LLC4, in 2008. “Market conditions are now extremely tough, especially in the key US market, and the Tatas will need to invest in a lot of brand building to make and keep JLR profitable.”5 - Ian Gomes, Global Head, Emerging Markets, KPMG, in 2008. -

Austin Motor Company

Austin Motor Company Few names in British motoring history are better known than that of Austin. For many years the company claimed that ‘You buy a car but you invest in an Austin’. A young Herbert Austin (1866–1941) travelled to Australia in 1884 seeking his fortune. In mid 1886 he began working for Frederick Wolseley’s Sheep Shearing Machine Company in Sydney. Austin returned to England with Wolseley in 1889 to establish a new factory in Birmingham, where he became Works Manager. Austin built himself a car in 1895/6 followed a few months later by a second for Wolseley, a production model followed in 1899. A new company, backed by Vickers, bought the car making interests of the Wolseley Company in 1901 with Austin taking a leading role. Following a disagreement over engine design in 1905 Austin left, setting up his own Austin Motor Company in a disused printing works at Longbridge in December of that year. The first Austin was a 4 cylinder 5182cc 25/30hp model which became available in the spring of 1906. This was replaced by the 4396cc 18/24 in 1907. 5838cc 40hp and 6 cylinder 8757cc 60hp models were also produced. The 6 cylinder engine also formed the basis for a 9657cc 100hp engine used in cars for the 1908 Grand Prix. A 7hp single cylinder car was marketed in 1910/11. The company expanded rapidly, output growing from 200 cars in 1910 to 1100 in 1912. By 1914 there was a three model line-up of Ten, Twenty and Thirty. The Austin Company underwent a massive expansion during World War I with the workforce growing from 2,600 to more than 22,000. -

The Triumph Trumpet Is the Magazine of the Triumph Car Club of Victoria, Inc

March 2019 TrThue mpet The Triumph Car Club of Victoria Magazine General Meetings are held monthly on the third Wednesday of the month, except for the month of December and the month in which an AGM is held. The standard agenda for the General Meetings is: • Welcome address • Guest Speaker / Special Presentations • Apologies, Minutes & Secretary’s Report • Treasurer’s Report • Editor’s Report • Event Coordinator’s Report • Membership Secretary’s Report • Library, Tools & Regalia Report • Triumph Trading Report • AOMC Report • Any other business. The order of the agenda is subject to alteration on the night by the chairman. Extra agenda items should be notified to the attention of the Secretary via email to [email protected] The minutes of monthly general meetings are available for reference in the Members Only section of the website. A few hard copies of the prior month’s minutes will be available at each monthly meeting for reference. Please email any feedback to the Secretary at [email protected] The Triumph Trumpet is the magazine of the Triumph Car Club of Victoria, Inc. (Reg. No. A0003427S) Front Cover Photograph 2 Editorial 3 Upcoming Events! 4 Smoke Signals 5 The Triumph Car Club of Victoria is a Great Australian Rally/Cruden Farm 67 participating member of the Association Drive Your Triumph Day 812 of Motoring Clubs. Member Profile – Ryan Pillay 1314 The TCCV is an Authorised Club under Power Steering 1516 the VicRoads Club Permit Scheme. Harry & the European Connections1617 History of Lucas Electrics 1826 Articles in the Triumph Trumpet may be quoted without permission, however, due acknowledgment must be made. -

May 2017 Crankhandle

MAY 2017 The Official magazine of the GOLD COAST ANTIQUE AUTO CLUB Austin Se7en outside our clubhouse Crankhandle News GCAAC COMMITTEE Position Name Phone Email President David Mitchell 5577 1787 [email protected] Vice President Peter Amey 5525 0250 [email protected] 0407 374 196 Secretary Richard Brown 0417 704 726 [email protected] Treasurer Colin Hayes 5525 3312 [email protected] 0409 825 913 Events coordinator John Talbot 0421 185 419 [email protected] Dating Officer Bill Budd 5535 8882 [email protected] 0409 358 888 Publicity Officer John Talbot 0421 185 419 [email protected] Editor Peter A. Jones 0413 379 410 [email protected] Spare parts & prop- Graham 5554 5659 [email protected] erty Tattersall Librarian/Historian Wayne Robson 5522 8000 [email protected] 0409 610 229 Hall & Social Officer Pam Giles 0400 278 807 [email protected] Gold Coast Antique Auto club: PO Box 228, Mudgeeraba, Qld, 4213 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.gcaac.com.au Club meetings are held 2nd Monday of every month (except January) at 7.00pm for 7.30pm start. Visitors welcome Street Address: 238 Mudgeeraba Road, Mudgeeraba Q 4213 Life Members: Graham Hetherington, Peter Harris, Margaret Hession, John Wood, Graham Tattersall DISCLAIMER: The opinions expressed within are not necessarily shared by the editor or officers of the GCAAC. Whilst all care is taken to ensure the technical information and advice offered in these pages is correct, the editor and officers of the GCAAC cannot be held responsible for any problems that may occur from acting on such advice and information.