Rural France, War, Commemoration and Memory the Relationship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROVENCE! HOW to PROVENCE Like a Local in Nature with Family Around the Arts

OH LA LA… PROVENCE! HOW TO PROVENCE Like a local In nature With family Around the arts WHERE TO EAT Apéro hour How to play pétanque Must do’s for fall PROVENCE BASTILLE DAYS PÉTANQUE! PASTIS! FANTASTIC FRENCH FOOD! IN NYC July 9th - 15th 11 French restaurants Brooklyn block party Provence FÊTE FRANCE’S Bastille Days INDEPENDENCE DAY IN NYC! July 9th - 15th, 2018 At 17 years and counting, Provence Bastille Days gives New Yorkers a glimpse into the laidback lifestyle, flavors, and traditions of Provence that has lured so many to its hilltop villages, its inviting beaches, and its sprawling vineyards. Curious about how to play pétanque? Want to know the proper way to drink pastis? Enjoy Bastille Day bonhomie from July 9th to July 15th with celebratory bites, sips, and tunes served up all across the city. BASTILLE DAY, THE BROOKLYN WAY THE PLEASURES OF PROVENCE Voila! Here’s where you can NO PASSPORT REQUIRED get your Provence on For our grand finale on Sunday, July 15th, Brooklyn’s Smith Street will be transformed into the sun-kissed south of • Mominette: 221 Knickerbocker Ave, Brooklyn • Le Gamin: France. The pavement will be covered in sand pétanque courts, glasses Savor a special Provençal menu and aperitifs served 108 Franklin St, Brooklyn • Nice Matin: The Lucerne Hotel 201 W 79th St will be filled with rosé, and plates will be topped with tasty bites from up by 10 of NYC’s favorite French restaurants. • Café du soleil: 2723 Broadway Bar Tabac. Part convivial street party, part pétanque tournament, the fun Tap your feet to festive French tunes bands will pop up • Chez Oskar: 310 Malcolm X Blvd, Brooklyn festivities will go all day from noon to 10 pm. -

Mise En Page 1

E duvA MM R RA OG R P du 1 er au 12 octobre 2014 D es m us a to nif à w est tes atio ver r ww ns gratuites, ou .f .fe ce tedelascien Sommaire 4-11 Des manifestations près de chez vous • Cotignac / Entrecastaux • La Valette-du-Var • Saint-Maximin • Fréjus • Méounes / La Garde • Saint-Zacharie • Hyères • Ollioules • Signes • La Cadière d’Azur • Régusse • Toulon • La Garde • Rians • Tourtour • La Seyne-sur-Mer • Saint-Cyr-sur-Mer • Tourves / Puget-sur-Argens 12-16 village des Sciences de La Seyne-sur-Mer 17-18 village des Sciences de Rians 19 Le calendrier des manifestations 2 3 stations Des manife vous chez ès de certaines pr concerner es peuvent rifier la ères minut ations et vé ns de derni s manifest .fr modificatio tions sur le ascience vendredi 10, 19h Des s d'informa .fetedel s. Pour plu le site www Conférence : microflore intestinale, ces mi - anifestation z-vous sur m lisée, rende crobes qui nous veulent du bien ation actua programm COMMunE D’HyERES Par Jean Christophe LAGIER, CNRS Contact : Jean-Louis PACITTO, tel : 06 13 77 25 11 mail : [email protected] fRéjuS Samedi 12,15h AMPHibiuM, Table ronde : Le téléphone mobile… Où va- Visite COtiGnAC / territoire écomimétique t-on ? MAiSOn DES éCOnOMiES D’énERGiES Ecomimetica : territoire créatif Avec : Frédéric CARRIERE, Directeur de re - EntRECAStAux Et D’EAu cherche CNRS, André NIEOULLON, Professeur à bio-inspiré l’AMU, Louis PORTE, Professeur émérite AMU ADEE, 842 rue Jean Giono Résidence Antoine Caire GEnS Du fROiD Contact : Jean-François LANIER, tel : 04 94 53 90 15 Samedi 11 mail : [email protected] Les horaires et l’itinéraire vous seront COtiGnAC Et EntRECAStEAux communiqués lors de votre inscription. -

Starring Hitler! Adolf Hitler As the Main Character in Twentieth-First Century French Fiction," Studies in 20Th & 21St Century Literature: Vol

Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature Volume 43 Issue 2 Article 44 October 2019 Starring Hitler! Adolf Hitler as the Main Character in Twentieth- First Century French Fiction Marion Duval The College of Wooster, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons, Holocaust and Genocide Studies Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Duval, Marion (2019) "Starring Hitler! Adolf Hitler as the Main Character in Twentieth-First Century French Fiction," Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 43: Iss. 2, Article 44. https://doi.org/10.4148/ 2334-4415.2076 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Starring Hitler! Adolf Hitler as the Main Character in Twentieth-First Century French Fiction Abstract Adolf Hitler has remained a prominent figure in popular culture, often portrayed as either the personification of evil or as an object of comedic ridicule. Although Hitler has never belonged solely to history books, testimonials, or documentaries, he has recently received a great deal of attention in French literary fiction. This article reviews three recent French novels by established authors: La part de l’autre (The Alternate Hypothesis) by Emmanuel Schmitt, Lui (Him) by Patrick Besson and La jeunesse mélancolique et très désabusée d’Adolf Hitler (Adolf Hitler’s Depressed and Very Disillusioned Youth) by Michel Folco; all of which belong to the Twenty-First Century French literary trend of focusing on Second World War perpetrators instead of their victims. -

LES VŒUX DE REGROUPEMENT DE COMMUNES Vœux

LES VŒUX DE REGROUPEMENT DE COMMUNES Vœux de regroupement : porte sur un support de poste choisi dans l’ensemble des communes comprises dans le regroupement. Les regroupements de communes correspondent généralement aux circonscriptions des inspecteurs. Regroupement de BRIGNOLES Regroupement de DRAGUIGNAN COTIGNAC BRIGNOLES CABASSE AIGUINES AMPUS SILLANS LA CASCADE LA CELLE CORRENS TOURVES DRAGUIGNAN TRANS EN PROVENCE BAUDUEN SALERNES LES SALLES/VERDON LORGUES MONTFORT S/ARGENS CARCES VILLECROZE AUPS LE THORONET ENTRECASTEAUX REGUSSE ARTIGNOSC/VERDON CAMPS LA SOURCE CABASSE TOURTOUR FLAYOSC ST-ANTONIN DU VAR LE VAL BRAS VINS SUR CARAMY Regroupement de ST RAPHAEL – FREJUS (écoles ventilées sur deux circonscriptions) FREJUS SAINT RAPHAEL Regroupement de CUERS BELGENTIER COLLOBRIERES MEOUNES Regroupement de HYERES LA FARLEDE PIERREFEU du VAR BORMES-LES-MIMOSAS HYERES SOLLIES VILLE CUERS LA LONDE DES MAURES SOLLIES TOUCAS SOLLIES PONT Regroupement de LA SEYNE Regroupement de LA GARDE ( écoles ventilées sur deux circonscriptions ) CARQUEIRANNE LA GARDE LE PRADET LA CRAU LA SEYNE SAINT MANDRIER Regroupement de SIX FOURS SIX-FOURS-LES PLAGES OLLIOULES Regroupement de GAREOULT Regroupement LE MUY BESSE/ISSOLE CARNOULES FLASSANS/ISSOLE LES ARCS LE MUY GAREOULT FORCALQUEIRET LA ROQUEBRUSSANE LES MAYONS LE LUC GONFARON MAZAUGUES SAINTE ANASTASIE TARADEAU VIDAUBAN NEOULES NANS LES PINS SAINT ZACHARIE LE CANNET DES MAURE PIGNANS PLAN D’AUPS ROCBARON PUGET VILLE Regroupement de STE MAXIME Regroupement de ST MAXIMIN CAVALAIRE/MER COGOLIN LA CROIX VALMER -

DP Musée De La Libération UK.Indd

PRESS KIT LE MUSÉE DE LA LIBÉRATION DE PARIS MUSÉE DU GÉNÉRAL LECLERC MUSÉE JEAN MOULIN OPENING 25 AUGUST 2019 OPENING 25 AUGUST 2019 LE MUSÉE DE LA LIBÉRATION DE PARIS MUSÉE DU GÉNÉRAL LECLERC MUSÉE JEAN MOULIN The musée de la Libération de Paris – musée-Général Leclerc – musée Jean Moulin will be ofcially opened on 25 August 2019, marking the 75th anniversary of the Liberation of Paris. Entirely restored and newly laid out, the museum in the 14th arrondissement comprises the 18th-century Ledoux pavilions on Place Denfert-Rochereau and the adjacent 19th-century building. The aim is let the general public share three historic aspects of the Second World War: the heroic gures of Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque and Jean Moulin, and the liberation of the French capital. 2 Place Denfert-Rochereau, musée de la Libération de Paris – musée-Général Leclerc – musée Jean Moulin © Pierre Antoine CONTENTS INTRODUCTION page 04 EDITORIALS page 05 THE MUSEUM OF TOMORROW: THE CHALLENGES page 06 THE MUSEUM OF TOMORROW: THE CHALLENGES A NEW HISTORICAL PRESENTATION page 07 AN EXHIBITION IN STEPS page 08 JEAN MOULIN (¡¢¢¢£¤) page 11 PHILIPPE DE HAUTECLOCQUE (¢§¢£¨) page 12 SCENOGRAPHY: THE CHOICES page 13 ENHANCED COLLECTIONS page 15 3 DONATIONS page 16 A MUSEUM FOR ALL page 17 A HERITAGE SETTING FOR A NEW MUSEUM page 19 THE INFORMATION CENTRE page 22 THE EXPERT ADVISORY COMMITTEE page 23 PARTNER BODIES page 24 SCHEDULE AND FINANCING OF THE WORKS page 26 SPONSORS page 27 PROJECT PERSONNEL page 28 THE CITY OF PARIS MUSEUM NETWORK page 29 PRESS VISUALS page 30 LE MUSÉE DE LA LIBÉRATION DE PARIS MUSÉE DU GÉNÉRAL LECLERC MUSÉE JEAN MOULIN INTRODUCTION New presentation, new venue: the museums devoted to general Leclerc, the Liberation of Paris and Resistance leader Jean Moulin are leaving the Gare Montparnasse for the Ledoux pavilions on Place Denfert-Rochereau. -

Murder in Aubagne: Lynching, Law, and Justice During the French

This page intentionally left blank Murder in Aubagne Lynching, Law, and Justice during the French Revolution This is a study of factions, lynching, murder, terror, and counterterror during the French Revolution. It examines factionalism in small towns like Aubagne near Marseille, and how this produced the murders and prison massacres of 1795–1798. Another major theme is the conver- gence of lynching from below with official terror from above. Although the Terror may have been designed to solve a national emergency in the spring of 1793, in southern France it permitted one faction to con- tinue a struggle against its enemies, a struggle that had begun earlier over local issues like taxation and governance. This study uses the tech- niques of microhistory to tell the story of the small town of Aubagne. It then extends the scope to places nearby like Marseille, Arles, and Aix-en-Provence. Along the way, it illuminates familiar topics like the activity of clubs and revolutionary tribunals and then explores largely unexamined areas like lynching, the sociology of factions, the emer- gence of theories of violent fraternal democracy, and the nature of the White Terror. D. M. G. Sutherland received his M.A. from the University of Sussex and his Ph.D. from the University of London. He is currently professor of history at the University of Maryland, College Park. He is the author of The Chouans: The Social Origins of Popular Counterrevolution in Upper Brittany, 1770–1796 (1982), France, 1789–1815: Revolution and Counterrevolution (1985), and The French Revolution, 1770– 1815: The Quest for a Civic Order (2003) as well as numerous scholarly articles. -

UNIVERSITE DE TOULON (VAR) Référence GALAXIE : 4194

UNIVERSITE DE TOULON (VAR) Référence GALAXIE : 4194 Numéro dans le SI local : Référence GESUP : Corps : Maître de conférences Article : 26-I-1 Chaire : Non Section 1 : 01-Droit privé et sciences criminelles Section 2 : Section 3 : Profil : Maître de conférences « Droit du travail,, droit social - Contentieux » Job profile : Labour law Research fields EURAXESS : Juridical sciences Labour law Implantation du poste : 0830766G - UNIVERSITE DE TOULON (VAR) Localisation : TOULON et DRAGUIGNAN Code postal de la localisation : Etat du poste : Vacant Adresse d'envoi du Universite de Toulon dossier : Direction des ressources humaine Service developpement RH 83130 - LA GARDE Contact Mathilde CHARPENTIER administratif : Responsable recrutement enseignants N° de téléphone : 04 94 14 29 73 04 94 14 28 85 N° de Fax : Indisponible Email : [email protected] Date de prise de fonction : 01/09/2019 Mots-clés : droit du travail ; droit social ; Profil enseignement : Composante ou UFR : UFR Faculte de droit Référence UFR : Profil recherche : Laboratoire 1 : EA3164 (200014463A) - CENTRE D'ETUDES ET DE RECHERCHE SUR LES CONTENTIEUX - EA 3164 Dossier Papier NON Dossier numérique physique (CD, NON DVD, clé USB) Dossier transmis par courrier NON e-mail gestionnaire électronique Application spécifique OUI URL application https://callisto.univ-tln.fr/EsupDematEC/login Poste ouvert également aux personnes 'Bénéficiaires de l'Obligation d'Emploi' mentionnées à l'article 27 de la loi n° 84- 16 du 11 janvier 1984 modifiée portant dispositions statutaires relatives à la fonction publique de l'Etat (situations de handicap). Le poste sur lequel vous candidatez est susceptible d'être situé dans une "zone à régime restrictif" au sens de l'article R.413-5-1 du code pénal. -

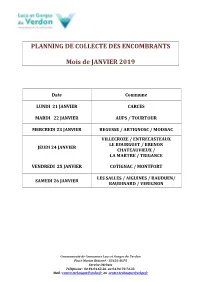

PLANNING DE COLLECTE DES ENCOMBRANTS Mois De JANVIER

PLANNING DE COLLECTE DES ENCOMBRANTS Mois de JANVIER 2019 Date Commune LUNDI 21 JANVIER CARCES MARDI 22 JANVIER AUPS / TOURTOUR MERCREDI 23 JANVIER REGUSSE / ARTIGNOSC / MOISSAC VILLECROZE / ENTRECASTEAUX LE BOURGUET / BRENON JEUDI 24 JANVIER CHATEAUVIEUX / LA MARTRE / TRIGANCE VENDREDI 25 JANVIER COTIGNAC / MONTFORT LES SALLES / AIGUINES / BAUDUEN/ SAMEDI 26 JANVIER BAUDINARD / VERIGNON Communauté de Communes Lacs et Gorges du Verdon Place Martin Bidouré - 83630 AUPS Service Déchets Téléphone : 04.94.04.63.36. ou 04.94.70.74.33. Mail : [email protected] ou [email protected] PLANNING DE COLLECTE DES ENCOMBRANTS Mois de FEVRIER 2019 Date Commune LUNDI 18 FEVRIER CARCES MARDI 19 FEVRIER AUPS/TOURTOUR MERCREDI 20 FEVRIER REGUSSE / ARTIGNOSC /MOISSAC VILLECROZE/ENTRECASTEAUX LE BOURGUET/ BRENON JEUDI 21 FEVRIER CHATEAUVIEUX/LA MARTRE/TRIGANCE VENDREDI 22 FEVRIER COTIGNAC/ MONTFORT LES SALLES / AIGUINES /BAUDUEN SAMEDI 23 FEVRIER BAUDINARD / VERIGNON Communauté de Communes Lacs et Gorges du Verdon Place Martin Bidouré - 83630 AUPS Service Déchets Téléphone : 04.94.04.63.36. ou 04.94.70.74.33. Mail : [email protected] ou [email protected] PLANNING DE COLLECTE DES ENCOMBRANTS MOIS DE MARS 2019 Date Commune LUNDI 25 MARS CARCES MARDI 26 MARS AUPS / TOURTOUR MERCREDI 27 MARS REGUSSE / ARTIGNOSC / MOISSAC VILLECROZE / ENTRECASTEAUX LE BOURGUET/ BRENON JEUDI 28 MARS CHATEAUVIEUX / LA MARTRE / TRIGANCE VENDREDI 29 MARS COTIGNAC / MONTFORT LES SALLES / AIGUINES / BAUDUEN SAMEDI 30 MARS BAUDINARD / VERIGNON Communauté -

Luxembourg Resistance to the German Occupation of the Second World War, 1940-1945

LUXEMBOURG RESISTANCE TO THE GERMAN OCCUPATION OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR, 1940-1945 by Maureen Hubbart A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Major Subject: History West Texas A&M University Canyon, TX December 2015 ABSTRACT The history of Luxembourg’s resistance against the German occupation of World War II has rarely been addressed in English-language scholarship. Perhaps because of the country’s small size, it is often overlooked in accounts of Western European History. However, Luxembourgers experienced the German occupation in a unique manner, in large part because the Germans considered Luxembourgers to be ethnically and culturally German. The Germans sought to completely Germanize and Nazify the Luxembourg population, giving Luxembourgers many opportunities to resist their oppressors. A study of French, German, and Luxembourgian sources about this topic reveals a people that resisted in active and passive, private and public ways. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Elizabeth Clark for her guidance in helping me write my thesis and for sharing my passion about the topic of underground resistance. My gratitude also goes to Dr. Brasington for all of his encouragement and his suggestions to improve my writing process. My thanks to the entire faculty in the History Department for their support and encouragement. This thesis is dedicated to my family: Pete and Linda Hubbart who played with and took care of my children for countless hours so that I could finish my degree; my husband who encouraged me and always had a joke ready to help me relax; and my parents and those members of my family living in Europe, whose history kindled my interest in the Luxembourgian resistance. -

July 2019 Newsletter N0 205 Draguignan Tour

British Association of the Var Putting people and social needs together since 1998 Association Loi 1901 No W831001750 www.baofthevar.co m July 2019 Newsletter N0 205 Draguignan Tour Richard Stombio, the Maire of Draguignan, had very generously agreed to make a gap in his very busy timetable to act as our personal guide around Draguignan. After several months of planning, the tour took place on 7 June commencing at the Mairie, where we were greeted by the Maire at the reception from where we proceeded to the council chamber. We were pleased to be joined for the occasion by officers of the British and American army. The Maire made some emotional comments about the relevance of the date, being the day following the anniversary of D Day, and this was followed by an in-depth history of the city of Draguignan and its emblem, the dragon. The town had a rich history being made, at one time, the capital of Provence located on a main pilgrimage route. At one stage there were 7000 sheep around the town and only 4000 inhabitants. We were then shown the historic part of the Mairie and then the Maire’s office where Liz Morgan was offered the seat of power! The tour then proceeded uphill along the main shopping street and took in various architectural features and the original town gates. We were finally taken to the elevated tower, where we were treated to magnificent views of the town and surrounding area and then we were taken inside the adjacent church which dates back to the 12th century. -

Criticism of “Fascist Nostalgia” in the Political Thought of the New Right

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS WRATISLAVIENSIS No 3866 Studia nad Autorytaryzmem i Totalitaryzmem 40, nr 3 Wrocław 2018 DOI: 10.19195/2300-7249.40.3.6 JOANNA SONDEL-CEDARMAS ORCID: 0000-0002-3037-9264 Uniwersytet Jagielloński Criticism of “fascist nostalgia” in the political thought of the New Right The seizure of power by the National Liberation Committee on 25th April, 1945 and the establishment of the republic on 2nd June, 1946 constituted the symbolic end to Mussolini’s dictatorship that had lasted for more than 20 years. However, it emerged relatively early that fascism was not a defi nitively closed chapter in the political and social life of Italy. As early as June of 1946, after the announcement of a presidential decree granting amnesty for crimes committed during the time of the Nazi-Fascist occupation between 1943 and 1945, the country saw a withdrawal from policies repressive towards fascists.1 Likewise, the national reconciliation policy gradually implemented in the second half of the 1940s by the government of Alcide De Gasperi, aiming at pacifying the nation and fostering the urgent re- building of the institution of the state, contributed to the emergence of ambivalent approaches towards Mussolini’s regime. On the one hand, Italy consequently tried to build its institutional and political order in clear opposition towards fascism, as exemplifi ed, among others, by a clause in the Constitution of 1947 that forbade the establishment of any form of fascist party, as well as the law passed on 20th June, 1 Conducted directly after the end of WW II, the epurazione action (purifi cation) that aimed at uprooting fascism, was discontinued on 22nd June 1946, when a decree of president Enrico De Nicola granting amnesty for crimes committed during the Nazi-Fascist occupation of Italy between 1943–1945 was implemented. -

H-France Review Volume 18 (2018) Page 1

H-France Review Volume 18 (2018) Page 1 H-France Review Vol. 18 (March 2018), No. 49 Sarah Shurts, Resentment and the Right: French Intellectual Identity Reimagined, 1898-2000. Newark/Lanham: University of Delaware Press/Rowman & Littlefield, 2017. xii + 337 pp. Notes, bibliography, and index. $110.00 U.S. (hardcover). ISBN 978-1-61149-634-5. Review by Sean Kennedy, University of New Brunswick at Fredericton. Presenting the history of French intellectuals in the modern era as a struggle between left and right is a long-established tradition, but in Resentment and the Right Sarah Shurts offers a fresh and compelling perspective. By identifying a recurring cycle of contestation over identity that ties in with long-standing debates over how to categorize the far right, the significance of the left-right dichotomy, and the character of French intellectual life, Shurts highlights the persistence of a distinctive pattern of extreme-right intellectual engagement. Ambitious in scope yet also featuring close analyses of prominent and less-prominent thinkers, her book is likely to spark further debate, and deserves considerable admiration. Well aware that she is on highly contested ground, Shurts carefully delineates her definitions of the terms ‘extreme right’ and ‘intellectual.’ With respect to the former she notes a veritable “wild west of terminology” (p. 15), the legacy of a long debate over the significance of fascism in France and the difficulties inherent in categorizing a diverse, often fractious political tradition. As for intellectuals, definitions tend to focus either upon values or sociological characteristics. Faced with various interpretive possibilities Shurts seeks to, borrowing a phrase from historian John Sweets, “hold that pendulum,” avoiding interpretive extremes.[1] In dealing with the extreme right, she concedes the findings of scholars who stress its diversity, the porosity of the left-right dichotomy as suggested by “crossover” figures, and the patterns of sociability shared by left and right-wing intellectuals.