BC Caridea Shrimp Key to Families Karl P. Kuchnow and Aaron

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Classification of Living and Fossil Genera of Decapod Crustaceans

RAFFLES BULLETIN OF ZOOLOGY 2009 Supplement No. 21: 1–109 Date of Publication: 15 Sep.2009 © National University of Singapore A CLASSIFICATION OF LIVING AND FOSSIL GENERA OF DECAPOD CRUSTACEANS Sammy De Grave1, N. Dean Pentcheff 2, Shane T. Ahyong3, Tin-Yam Chan4, Keith A. Crandall5, Peter C. Dworschak6, Darryl L. Felder7, Rodney M. Feldmann8, Charles H. J. M. Fransen9, Laura Y. D. Goulding1, Rafael Lemaitre10, Martyn E. Y. Low11, Joel W. Martin2, Peter K. L. Ng11, Carrie E. Schweitzer12, S. H. Tan11, Dale Tshudy13, Regina Wetzer2 1Oxford University Museum of Natural History, Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3PW, United Kingdom [email protected] [email protected] 2Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 900 Exposition Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90007 United States of America [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 3Marine Biodiversity and Biosecurity, NIWA, Private Bag 14901, Kilbirnie Wellington, New Zealand [email protected] 4Institute of Marine Biology, National Taiwan Ocean University, Keelung 20224, Taiwan, Republic of China [email protected] 5Department of Biology and Monte L. Bean Life Science Museum, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602 United States of America [email protected] 6Dritte Zoologische Abteilung, Naturhistorisches Museum, Wien, Austria [email protected] 7Department of Biology, University of Louisiana, Lafayette, LA 70504 United States of America [email protected] 8Department of Geology, Kent State University, Kent, OH 44242 United States of America [email protected] 9Nationaal Natuurhistorisch Museum, P. O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands [email protected] 10Invertebrate Zoology, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, 10th and Constitution Avenue, Washington, DC 20560 United States of America [email protected] 11Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore, Science Drive 4, Singapore 117543 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 12Department of Geology, Kent State University Stark Campus, 6000 Frank Ave. -

Two Freshwater Shrimp Species of the Genus Caridina (Decapoda, Caridea, Atyidae) from Dawanshan Island, Guangdong, China, with the Description of a New Species

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 923: 15–32 (2020) Caridina tetrazona 15 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.923.48593 RESEarcH articLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Two freshwater shrimp species of the genus Caridina (Decapoda, Caridea, Atyidae) from Dawanshan Island, Guangdong, China, with the description of a new species Qing-Hua Chen1, Wen-Jian Chen2, Xiao-Zhuang Zheng2, Zhao-Liang Guo2 1 South China Institute of Environmental Sciences, Ministry of Ecology and Environment, Guangzhou 510520, Guangdong Province, China 2 Department of Animal Science, School of Life Science and Enginee- ring, Foshan University, Foshan 528231, Guangdong Province, China Corresponding author: Zhao-Liang Guo ([email protected]) Academic editor: I.S. Wehrtmann | Received 19 November 2019 | Accepted 7 February 2020 | Published 1 April 2020 http://zoobank.org/138A88CC-DF41-437A-BA1A-CB93E3E36D62 Citation: Chen Q-H, Chen W-J, Zheng X-Z, Guo Z-L (2020) Two freshwater shrimp species of the genus Caridina (Decapoda, Caridea, Atyidae) from Dawanshan Island, Guangdong, China, with the description of a new species. ZooKeys 923: 15–32. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.923.48593 Abstract A faunistic and ecological survey was conducted to document the diversity of freshwater atyid shrimps of Dawanshan Island. Two species of Caridina that occur on this island were documented and discussed. One of these, Caridina tetrazona sp. nov. is described and illustrated as new to science. It can be easily distinguished from its congeners based on a combination of characters, which includes a short rostrum, the shape of the endopod of the male first pleopod, the segmental ratios of antennular peduncle and third maxilliped, the slender scaphocerite, and the absence of a median projection on the posterior margin. -

Shrimp Fishing in Mexico

235 Shrimp fishing in Mexico Based on the work of D. Aguilar and J. Grande-Vidal AN OVERVIEW Mexico has coastlines of 8 475 km along the Pacific and 3 294 km along the Atlantic Oceans. Shrimp fishing in Mexico takes place in the Pacific, Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean, both by artisanal and industrial fleets. A large number of small fishing vessels use many types of gear to catch shrimp. The larger offshore shrimp vessels, numbering about 2 212, trawl using either two nets (Pacific side) or four nets (Atlantic). In 2003, shrimp production in Mexico of 123 905 tonnes came from three sources: 21.26 percent from artisanal fisheries, 28.41 percent from industrial fisheries and 50.33 percent from aquaculture activities. Shrimp is the most important fishery commodity produced in Mexico in terms of value, exports and employment. Catches of Mexican Pacific shrimp appear to have reached their maximum. There is general recognition that overcapacity is a problem in the various shrimp fleets. DEVELOPMENT AND STRUCTURE Although trawling for shrimp started in the late 1920s, shrimp has been captured in inshore areas since pre-Columbian times. Magallón-Barajas (1987) describes the lagoon shrimp fishery, developed in the pre-Hispanic era by natives of the southeastern Gulf of California, which used barriers built with mangrove sticks across the channels and mouths of estuaries and lagoons. The National Fisheries Institute (INP, 2000) and Magallón-Barajas (1987) reviewed the history of shrimp fishing on the Pacific coast of Mexico. It began in 1921 at Guaymas with two United States boats. -

Color Patterns of the Shrimps Heptacarpus Pictus and H. Paludicola (Caridea: Hippolytidae)

MARINE BIOLOGY Marine Biology 64, 141-152 (1981) © Springer-Verlag 1981 Color Patterns of the Shrimps Heptacarpus pictus and H. paludicola (Caridea: Hippolytidae) R. T. Bauer Department of Invertebrate Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution; Washington, D.C. 20560, USA Abstract coloration has been on the isopod Idothea montereyensis Maloney; Lee (1966 a,b, 1972) studied the biochemical Color patterns of the shallow-water shrimps Heptacarpus and cellular bases of color patterns and the ecology of pictus and H. paludicola are formed by chromatosomes color change. However, no caridean shrimp has been (usually termed chromatophores) located beneath the studied so thoroughly. Gamble and Keeble (1900) and translucent exoskeleton. Development of color patterns Keeble and Gamble (1900, 1904) described in detail the is related to size (age) and sex. The color expressed is chromatophores (chromatosomes in the modern usage of determined by the chromatosome pigment dispersion, Elofsson and Kauri, 1971) and coloration of the shrimp arrangement, and density. In populations with well- Hippolyte varians Leach. Chassard-Bouchaud (1965), in developed coloration (//. pictus from Cayucos, California, her extensive work on physiological and morphological 1976-1978,//. paludicola from ArgyleChannel, San Juan color change in caridean shrimp, described the chromato Island, Washington, June-July, 1978), prominent somes and illustrated the color morphs of H. varians, coloration was a characteristic of maturing females, Palaemoii squilla (L.), P. serratus (Pennant), Athanas breeding females, and some of the larger males. In the nitescens Leach, and Crangon crangon (L.). Carlisle and Morro Bay, California, population of H. paludicola Knowles (1959) give a brief review of color patterns in (sampled 1976-1978), color patterns were poorly decapod species. -

Suisun Marsh Fish Report 2015 Final

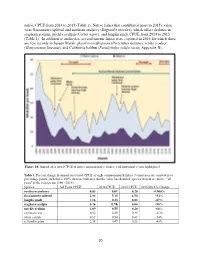

native CPUE from 2014 to 2015 (Table 1). Native fishes that contributed most to 2015's value were Sacramento splittail and northern anchovy (Engraulis mordax), which offset declines in staghorn sculpin, prickly sculpin (Cottus asper), and longfin smelt CPUE from 2014 to 2015 (Table 1). In addition to anchovies, several marine fishes were captured in 2016 for which there are few records in Suisun Marsh: plainfin midshipman (Porichthys notatus), white croaker (Genyonemus lineatus), and California halibut (Paralichthys californicus; Appendix B). Figure 14. Annual otter trawl CPUE of native and non-native fishes, with important events highlighted. Table 1. Percent change in annual otter trawl CPUE of eight common marsh fishes (% increases are equivalent to percentage points, such that a 100% increase indicates that the value has doubled; species in bold are native; "all years" is the average for 1980 - 2015). Species All Years CPUE 2014 CPUE 2015 CPUE 2015/2014 % Change northern anchovy 0.03 0.01 0.20 +1900% Sacramento splittail 2.84 5.15 6.90 +34% longfin smelt 1.16 0.23 0.03 -87% staghorn sculpin 0.26 0.16 0.00 -98% prickly sculpin 1.09 0.55 0.20 -64% common carp 0.52 0.49 0.19 -61% white catfish 0.63 0.94 0.43 -54% yellowfin goby 2.31 0.47 0.26 -45% 20 Beach Seines Annual beach seine CPUE in 2015 was similar to the average from 1980 to 2015 (57 fish per seine; Figure 15), declining mildly from 2014 to 2015 (62 and 52 per seine, respectively). CPUE declined slightly for both non-native and native fishes from 2014 to 2015 (Figure 15); as usual, non-native fish, dominated by Mississippi silversides (Menidia audens), were far more abundant in seine hauls than native fish (Table 2). -

New Records and Description of Two New Species Of

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 671: 131–153New (2017) records and description of two new species of carideans shrimps... 131 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.671.9081 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research New records and description of two new species of carideans shrimps from Bahía Santa María- La Reforma lagoon, Gulf of California, Mexico (Crustacea, Caridea, Alpheidae and Processidae) José Salgado-Barragán1, Manuel Ayón-Parente2, Pilar Zamora-Tavares2 1 Laboratorio de Invertebrados Bentónicos, Unidad Académica Mazatlán, Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México 2 Centro Universitario de Ciencias Agrope- cuarias, Universidad de Guadalajara, México Corresponding author: José Salgado-Barragán ([email protected]) Academic editor: S. De Grave | Received 4 May 2016 | Accepted 22 March 2017 | Published 27 April 2017 http://zoobank.org/9742DC49-F925-4B4B-B440-17354BDDB4B5 Citation: Salgado-Barragán J, Ayón-Parente M, Zamora-Tavares P (2017) New records and description of two new species of carideans shrimps from Bahía Santa María-La Reforma lagoon, Gulf of California, Mexico (Crustacea, Caridea, Alpheidae and Processidae). ZooKeys 671: 131–153. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.671.9081 Abstract Two new species of the family Alpheidae: Alpheus margaritae sp. n. and Leptalpheus melendezensis sp. n. are described from Santa María-La Reforma, coastal lagoon, SE Gulf of California. Alpheus margaritae sp. n. is closely related to A. antepaenultimus and A. mazatlanicus from the Eastern Pacific and to A. chacei from the Western Atlantic, but can be differentiated from these by a combination of characters, especially the morphology of the scaphocerite and the first pereopods. -

Crangon Franciscorum Class: Multicrustacea, Malacostraca, Eumalacostraca

Phylum: Arthropoda, Crustacea Crangon franciscorum Class: Multicrustacea, Malacostraca, Eumalacostraca Order: Eucarida, Decapoda, Pleocyemata, Caridea Common gray shrimp Family: Crangonoidea, Crangonidae Taxonomy: Schmitt (1921) described many duncle segment (Wicksten 2011). Inner fla- shrimp in the genus Crago (e.g. Crago fran- gellum of the first antenna is greater than ciscorum) and reserved the genus Crangon twice as long as the outer flagellum (Kuris et for the snapping shrimp (now in the genus al. 2007) (Fig. 2). Alpheus). In 1955–56, the International Mouthparts: The mouth of decapod Commission on Zoological Nomenclature crustaceans comprises six pairs of appendag- formally reserved the genus Crangon for the es including one pair of mandibles (on either sand shrimps only. Recent taxonomic de- side of the mouth), two pairs of maxillae and bate revolves around potential subgeneric three pairs of maxillipeds. The maxillae and designation for C. franciscorum (C. Neocran- maxillipeds attach posterior to the mouth and gon franciscorum, C. franciscorum francis- extend to cover the mandibles (Ruppert et al. corum) (Christoffersen 1988; Kuris and Carl- 2004). Third maxilliped setose and with exo- ton 1977; Butler 1980; Wicksten 2011). pod in C. franciscorum and C. alaskensis (Wicksten 2011). Description Carapace: Thin and smooth, with a Size: Average body length is 49 mm for single medial spine (compare to Lissocrangon males and 68 mm for females (Wicksten with no gastric spines). Also lateral (Schmitt 2011). 1921) (Fig. 1), hepatic, branchiostegal and Color: White, mottled with small black spots, pterygostomian spines (Wicksten 2011). giving gray appearance. Rostrum: Rostrum straight and up- General Morphology: The body of decapod turned (Crangon, Kuris and Carlton 1977). -

Pandalus Platyceros Range: Spot Prawn Inhabit Alaska to San Diego

Fishery-at-a-Glance: Spot Prawn Scientific Name: Pandalus platyceros Range: Spot Prawn inhabit Alaska to San Diego, California, in depths from 150 to 1,600 feet (46 to 488 meters). The areas where they are of higher abundance in California waters occur off of the Farallon Islands, Monterey, the Channel Islands and most offshore banks. Habitat: Juvenile Spot Prawn reside in relatively hard-bottom kelp covered areas in shallow depths, and adults migrate into deep water of 60.0 to 200.0 meters (196.9 to 656.2 feet). Size (length and weight): The Spot Prawn is the largest prawn in the North Pacific reaching a total length of 25.3 to 30.0 centimeters (10.0 to 12.0 inches) and they can weigh up to 120 grams (0.26 pound). Life span: Spot Prawn have a maximum observed age estimated at more than 6 years, but there are considerable differences in age and growth of Spot Prawns depending on the research and the area. Reproduction: The Spot Prawn is a protandric hermaphrodite (born male and change to female by the end of the fourth year). Spawning occurs once a year, and Spot Prawn typically mate once as a male and once or twice as a female. At sexual maturity, the carapace length of males reaches 1.5 inches (33.0 millimeters) and females 1.75 inches (44.0 millimeters). Prey: Spot Prawn feed on other shrimp, plankton, small mollusks, worms, sponges, and fish carcasses, as well as being detritivores. Predators: Spot Prawn are preyed on by larger marine animals, such as Pacific Hake, octopuses, and seals, as well as humans. -

Heptacarpus Paludicola Class: Malacostraca Order: Decapoda a Broken Back Shrimp Section: Caridea Family: Thoridae

Phylum: Arthropoda, Crustacea Heptacarpus paludicola Class: Malacostraca Order: Decapoda A broken back shrimp Section: Caridea Family: Thoridae Taxonomy: Local Heptacarpus species (e.g. Antennae: Antennal scale never H. paludicola and H. sitchensis) were briefly much longer than rostrum. Antennular considered to be in the genus Spirontocaris peduncle bears spines on each of the three (Rathbun 1904; Schmitt 1921). However members of Spirontocaris have two or more segments and stylocerite (basal, lateral spine supraorbital spines (rather than only one in on antennule) does not extend beyond the Heptacarpus). Thus a known synonym for H. first segment (Wicksten 2011). paludicola is S. paludicola (Wicksten 2011). Mouthparts: The mouth of decapod crustaceans comprises six pairs of Description appendages including one pair of mandibles Size: Individuals 20 mm (males) to 32 mm (on either side of the mouth), two pairs of (females) in length (Wicksten 2011). maxillae and three pairs of maxillipeds. The Illustrated specimen was a 30 mm-long, maxillae and maxillipeds attach posterior to ovigerous female collected from the South the mouth and extend to cover the mandibles Slough of Coos Bay. (Ruppert et al. 2004). Third maxilliped without Color: Variable across individuals. Uniform expodite and with epipods (Fig. 1). Mandible with extremities clear and green stripes or with incisor process (Schmitt 1921). speckles. Color can be deep blue at night Carapace: No supraorbital spines (Bauer 1981). Adult color patterns arise from (Heptacarpus, Kuris et al. 2007; Wicksten chromatophores under the exoskeleton and 2011) and no lateral or dorsal spines. are related to animal age and sex (e.g. Rostrum: Well-developed, longer mature and breeding females have prominent than carapace, extending beyond antennular color patters) (Bauer 1981). -

Antifouling Adaptations of Marine Shrimp (Decapoda: Caridea): Gill Cleaning Mechanisms and Grooming of Brooded Embryos

Zoological Journal oj the Linnean Society, 6i: 281-305. With 12 figures April 1979 Antifouling adaptations of marine shrimp (Decapoda: Caridea): gill cleaning mechanisms and grooming of brooded embryos RAYMOND T. BAUER Biological Sciences, California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, California, U.S.A. Accepted for publication September 1977 Gills in the branchial chambers of caridean shrimps, as well as the brooded embryos in females, are subject to fouling by particulate debris and epizoites. Important mechanisms for cleaning the gills are brushing of the gills by the grooming or cleaning chelipeds in some species, while in others, setae from the bases of the thoracic legs brush up among the gills during movement of the limbs (epipod- setobranch complexes). Setae of cleaning chelipeds and of epipod-setobranch complexes show- similar ultrastructural adaptions for scraping gill surfaces. Ablation of the cleaning chelipeds ol the shrimp Heptacarpm pictus results in severe fouling of the gills in experimenials, while those of controls remain clean, Embrvos brooded by female carideans are often brushed and jostled by the grooming chelipeds. In H. pictui. removal of the cleaning chelae results in heavier microbial and sediment fouling than in controls. KEY WO RDS: - shrimp - gills - grooming - cleaning - cpipods - sctobranchs - fouling - Decapoda - Caridea. CONTENTS Introduction 281 Methods 282 Results 284 Gill cleaning by the chelipeds 284 Gill cleaning by the epipod-setobranch complex 289 Experiments on the adaptive value of cheliped brushing in Heptacarpus pictus 292 Cleaning of brooded embryos 296 Experiments on the adaptive value of cheliped brushing of eggs in Heptacarpus pictus 297 Discussion 299 Adaptive value of gill cleaning mechanisms in caridean shrimp 299 Adaptive value of embryo brushing by females 301 Acknowledgements 302 References 302 INTRODUCTION Grooming behaviour is a frequent activity of caridean shrimp which appears to prevent epizoic and sediment fouling of the body (Bauer, 1975; Bauer, 1977, Bauer, 1978). -

OREGON ESTUARINE INVERTEBRATES an Illustrated Guide to the Common and Important Invertebrate Animals

OREGON ESTUARINE INVERTEBRATES An Illustrated Guide to the Common and Important Invertebrate Animals By Paul Rudy, Jr. Lynn Hay Rudy Oregon Institute of Marine Biology University of Oregon Charleston, Oregon 97420 Contract No. 79-111 Project Officer Jay F. Watson U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 500 N.E. Multnomah Street Portland, Oregon 97232 Performed for National Coastal Ecosystems Team Office of Biological Services Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Department of Interior Washington, D.C. 20240 Table of Contents Introduction CNIDARIA Hydrozoa Aequorea aequorea ................................................................ 6 Obelia longissima .................................................................. 8 Polyorchis penicillatus 10 Tubularia crocea ................................................................. 12 Anthozoa Anthopleura artemisia ................................. 14 Anthopleura elegantissima .................................................. 16 Haliplanella luciae .................................................................. 18 Nematostella vectensis ......................................................... 20 Metridium senile .................................................................... 22 NEMERTEA Amphiporus imparispinosus ................................................ 24 Carinoma mutabilis ................................................................ 26 Cerebratulus californiensis .................................................. 28 Lineus ruber ......................................................................... -

Crustacea, Decapoda, Dendrobranchiata and Caridea) from Off Northeastern Japan

Bull. Natl. Mus. Nat. Sci., Ser. A, 42(1), pp. 23–48, February 22, 2016 Additional Records of Deep-water Shrimps (Crustacea, Decapoda, Dendrobranchiata and Caridea) from off Northeastern Japan Tomoyuki Komai1 and Hironori Komatsu2 1 Natural History Museum and Institute, Chiba, 955–2 Aoba-cho, Chiba 260–8682, Japan E-mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Zoology, National Museum of Nature and Science, 4–1–1 Amakubo, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305–0005, Japan E-mail: [email protected] (Received 5 October 2015; accepted 22 December 2015) Abstract Four deep-water species of shrimps are newly recorded from off Tohoku District, northeastern Japan: Hepomadus gracialis Spence Bate, 1888 (Dendrobranchiata, Aristeidae), Pasiphaea exilimanus Komai, Lin and Chan, 2012 (Caridea, Pasiphaeidae), Nematocarcinus longirostris Spence Bate, 1888 (Caridea, Nematocarcinidae), and Glyphocrangon caecescens Anonymous, 1891 (Caridea, Glyphocrangonidae). Of them, the bathypelagic P. exilimanus is new to the Japanese fauna. The other three species are abyssobenthic, extending to depths greater than 3000 m, and thus have been rarely collected. The newly collected samples of H. gracialis enable us to reassess diagnostic characters of the species. Nematocarcinus longirostris is rediscovered since the original description, and the taxonomy of the species is reviewed. Glyphocrangon caecescens is the sole representative of the family extending to off northern Japan. Key words : Hepomadus gracialis, Pasiphaea exilimanus, Nematocarcinus longirostris, Glypho- crangon caecescens,