Unit 13 Moderates, Extremists and Revolutionaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Question Bank Mcqs TYBA Political Science Semester V 2019-20 Paper-6 Politics of Modern Maharashtra

Question Bank MCQs TYBA Political Science Semester V 2019-20 Paper-6 Politics of Modern Maharashtra 1. Who founded the SNDT University for women in 1916? a) M.G.Ranade b) Dhondo Keshav Karve c) Gopal Krishna Gokhale d) Bal Gangadhar Tilak 2. Who was associated with the Satyashodhak Samaj? a) Sri Narayan Guru b) Jyotirao Phule c) Dr. B. R. Ambedkar d) E.V. Ramaswamy Naicker 3. When was the Indian National Congress established? a) 1875 b) 1885 c) 1905 d) 1947 4. Which Marathi newspaper was published by Bal Gangadhar Tilak a) Kesari b) Poona Vaibhav c) Sakal d) Darpan 5. Which day is celebrated as the Maharashtra Day? a) 12th January b) 14th April c) 1st May d) 2nd October 6. Under whose leadership Samyukta Maharashtra Samiti was founded? a) Keshavrao Jedhe b) S. A. Sange c) Uddhavrao Patil d) Narayan Ganesh Gore 7. When did the Bilingual Bombay State come into existence? a) 1960 b) 1962 c) 1956 d) 1947 8. Which one of the following city comes under Vidarbha region? a) Nagpur b) Poona c) Aurangabad d) Raigad 9. Till 1948 Marathwada region was part of which of the following? a) Central Province and Berar b) Bombay State c) Hyderabad State d) Junagad 10. Dandekar Committee dealt with which of the following issues? a) Maharashtra’s Educational policy b) The problem of imbalance in development between different regions of Maharashtra c) Trade and commerce policy of Maharashtra d) Agricultural policy 11. Which one of the following is known as the financial capital of India? a) Pune b) Mumbai c) Nagpur d) Aurangabad 12. -

Indian Students, 'India House'

Wesleyan University The Honors College Empire and Assassination: Indian Students, ‘India House’, and Information Gathering in Great Britain, 1898-1911 by Paul Schaffel Class of 2012 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors in History Middletown, Connecticut April, 2012 2 Table Of Contents A Note on India Office Records.............................................................................................3 Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................4 Introduction-A Dynamic Relationship: Indian Students & the British Empire.....5 Separate Spheres on a Collision Course.................................................................................6 Internal Confusion ....................................................................................................................9 Outline...................................................................................................................................... 12 Previous Scholarship.............................................................................................................. 14 I. Indian Students & India House......................................................................... 17 Setting the Stage: Early Indian Student Arrivals in Britain .............................................. 19 Indian Student Groups ......................................................................................................... -

History of Modern Maharashtra (1818-1920)

1 1 MAHARASHTRA ON – THE EVE OF BRITISH CONQUEST UNIT STRUCTURE 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Political conditions before the British conquest 1.3 Economic Conditions in Maharashtra before the British Conquest. 1.4 Social Conditions before the British Conquest. 1.5 Summary 1.6 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES : 1 To understand Political conditions before the British Conquest. 2 To know armed resistance to the British occupation. 3 To evaluate Economic conditions before British Conquest. 4 To analyse Social conditions before the British Conquest. 5 To examine Cultural conditions before the British Conquest. 1.1 INTRODUCTION : With the discovery of the Sea-routes in the 15th Century the Europeans discovered Sea route to reach the east. The Portuguese, Dutch, French and the English came to India to promote trade and commerce. The English who established the East-India Co. in 1600, gradually consolidated their hold in different parts of India. They had very capable men like Sir. Thomas Roe, Colonel Close, General Smith, Elphinstone, Grant Duff etc . The English shrewdly exploited the disunity among the Indian rulers. They were very diplomatic in their approach. Due to their far sighted policies, the English were able to expand and consolidate their rule in Maharashtra. 2 The Company’s government had trapped most of the Maratha rulers in Subsidiary Alliances and fought three important wars with Marathas over a period of 43 years (1775 -1818). 1.2 POLITICAL CONDITIONS BEFORE THE BRITISH CONQUEST : The Company’s Directors sent Lord Wellesley as the Governor- General of the Company’s territories in India, in 1798. -

TYBA Political Science Syllabus

JAI HIND COLLEGE BASANTSING INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE & J.T.LALVANI COLLEGE OF COMMERCE (AUTONOMOUS) "A" Road, Churchgate, Mumbai - 400 020, India. Affiliated to University of Mumbai Program: B.A. Proposed Course: Political Science Semester VI Credit Based Semester and Grading System (CBGS) with effect from the academic year 2020-2021 1 TYBA Political Science Syllabus The academic year 2020-2021 Semester VI Course Course Title Credits Lectures Code /Week APOL601 Politics of Modern Maharashtra 5 4 APOL 602 Indian Political Thought 5 4 APOL603 India in World Politics 4.5 3 2 Semester IV – Theory Course Code : Politics of Modern Maharashtra (Credits:05 Lectures/Week: 04 ) APOL601 Objectives: ➢ To acquaint the students about thebackground in the formation of Maharashtra as a separate State and sub-regionalism thereafter. ➢ To introduce to the students about the impact of caste in Maharashtra Politics ➢ To create awareness about the social movements in Maharashtra. Outcomes: The Course aims to give the students background and understanding of the Politics of Modern Maharashtra. Historical Background 15 L Unit I 1.1 The Nationalist & Social Reform Movement 1.2 The Samyukta Maharashtra Movement & Its Aftermath 1.3 Sub-Regionalism Caste & Politics in Maharashtra 15 L Unit II 2.1 Dominant Caste Politics 2.2 Dalit Politics 2.3 OBC Political Economy & State Political Parties 15 L 3.1 Commerce, Politics & Industries Unit III 3.2 Politics of Cooperatives 3.3 State Political Parties Social Movements in Maharashtra 15 L 4.1 Farmers’ Movement (Shetkari Sanghatana, Swabhimani Shetkar Unit IV iSanghatana) 4.2 Movements Against Mega Projects (SEZ, Atomic Energy, etc) 4.3 Movements for Women’s Political Empowerment (Mahila Rajsatta Andolan, Yusuf Meherali Trust, Alochana) 3 References: 1. -

Lokamanya Tilak G

LOKAMANYA TILAK G. P. PRADHAN Foreword 1. Student and Teacher 2. Dedicated Journalist and Radical Nationalist 3. Four-Point Programme for Swarajya 4. An Ordeal 5. Broad-Based Political Movement 6. Scholar and Unique Leader Index Foreword The conquest of a nation by an alien power does not mean merely the loss of political freedom; it means the loss of one’s self-confidence too. Due to economic exploitation by the ruling power, the conquered nation is deprived of its natural resources and the people lose their sense of self-respect. Slavery leads to moral degradation and it thus becomes essential to restore self-confidence in the people so that they become fearless enough to participate in the struggle for freedom. In this respect Tilak played a pioneering role in India’s freedom struggle. For nearly four decades, he directed his energies to the task of creating the consciousness in the people that swarajya was their birthright. As editor of the Kesafy he opposed the tyrannical British rule and raised his voice against the injustices perpetrated on the Indians. With Chhatrapati Shivaji as his perennial source of inspiration, Tilak appealed to the people to emulate the great Maratha warrior and revive the glorious past. During the famine of 1896, Tilak made a fervent plea that the government must provide relief to the peasants, as stipulated in the Famine Relief Code. When Lord Curzon, the Viceroy of India, partitioned Bengal, the people of Bengal were enraged. Tilak, alongwith Lala Lajpat Rai and Bipin Chandra Pal, made the issue of partition a national cause and appealed to the people to assert their rights. -

22 Dr. Hemant Subhash Koli-Social

Online International Interdisciplinary Research Journal, {Bi-Monthly}, ISSN 2249-9598, Volume-10, July 2020 Special Issue The sculptor of the social educational revolution : Mahatma Jyotiba Phule aHemant S.Koli, bHasan.J.Tadvi a(MSW, M Phil, PhD), 11 Telephone Nagar West Jalgaon. Dist.Jalgaon, Maharashtra, India b(MSW, M Phil), Pandurang Saraf Nagar, Yaval, Dist.Jalgaon, Maharashtra, India Abstract If any great person leaves public life for any reason, only the thoughts of that person are left behind and even these thoughts may be limited to that particular period but the thoughts and deeds of Mahatma Jyotiba Phule are an exception. Mahatma Jyotiba Phule is a great 19th century thinker, social worker, writer, great revolutionary of social change and social reformer. He is known as the first social revolutionary in modern India. Because even though they are ordinary, they are unusual in thought and action. Mahatma Jyotiba Phule brought about great social and educational changes in India by carrying out various social works for the progress of the Dalit, exploited Bahujan community by enduring great hardships and humiliations. In it, she has tried to give new ideas to the Dalit community, women's education, compulsory and free primary education for children in rural areas, provision of trained teachers, education of Shudras for nation building, adoption of trilingual formula, scholarship and hostel facilities, and various developments for the betterment of the society. Studying the above work, Mahatma Jyotiba Phule's social, educational thoughts and actual work are inspiring and guiding for the society. In this research essay, a little light has been shed on the educational work of Mahatma Jyotiba Phule. -

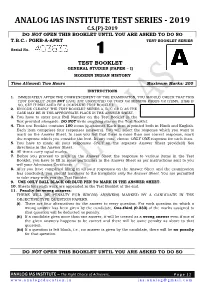

Analog Ias Institute Test Series - 2019 C.S.(P)-2019 Do Not Open This Booklet Until You Are Asked to Do So T.B.C.: Pgkb-A-Aprt Test Booklet Series

ANALOG IAS INSTITUTE TEST SERIES - 2019 C.S.(P)-2019 DO NOT OPEN THIS BOOKLET UNTIL YOU ARE ASKED TO DO SO T.B.C.: PGKB-A-APRT TEST BOOKLET SERIES Serial No. 1 TEST BOOKLET GENERAL STUDIES (PAPER – I) MODERN INDIAN HISTORY Time Allowed: Two Hours Maximum Marks: 200 INSTRUCTIONS 1. IMMEDIATELY AFTER THE COMMENCEMENT OF THE EXAMINATION, YOU SHOULD CHECK THAT THIS TEST BOOKLET DOES NOT HAVE ANY UNPRINTED OR TORN OR MISSING PAGES OR ITEMS, ET(c) IF SO, GET IT REPLACED BY A COMPLETE TEST BOOKLET. 2. ENCODE CLEARLY THE TEST BOOKLET SERIES A, B, C OR D AS THE CASE MAY BE IN THE APPROPRIATE PLACE IN THE ANSWER SHEET. 3. You have to enter your Roll Number on the Test Booklet in the Box provided alongside. DO NOT write anything else on the Test Booklet. 4. This test Booklet contains 100 items (questions). Each item is printed both in Hindi and English. Each item comprises four responses (answers). You will select the response which you want to mark on the Answer Sheet. In case you feel that there is more than one correct response, mark the response which you consider the best. In any case, choose ONLY ONE response for each item. 5. You have to mark all your responses ONLY on the separate Answer Sheet provide(d) See directions in the Answer Sheet. 6. All items carry equal marks. 7. Before you proceed to mark in the Answer Sheet the response to various items in the Test Booklet, you have to fill in some particulars in the Answer Sheet as per instructions sent to you will your Admission Certificate. -

Syllabus for TYBA Course :Political Science Semester : VI

JAI HIND COLLEGE AUTONOMOUS Syllabus for TYBA Course :Political Science Semester : VI Credit Based Semester & Grading System With effect from Academic Year 2018-19 1 List of Courses Course: Political Science Semester: VI NO. OF SR. COURSE NO. OF COURSE TITLE LECTURES NO. CODE CREDITS / WEEK TYBA 01 APOL601 Determinants of the Politics of 5 Maharashtra 02 APOL 602 Indian Political Thought 4 5 03 APOL603 India in World Politics 3 4.5 2 Semester VI – Theory Course Determinants of the Politics of Maharashtra Code : (Credits : 05 Lectures/Week: 04 ) APOL601 Objectives: To introduce to the students about how the pressure groups operate in urban and rural Maharashtra. To familiarize them about the functioning of the various political parties, contemporary issues and movements in Maharashtra. Outcomes: The students will be able to understand the fundamentals of the politics of Maharashtra. Political Economy of Maharashtra 15 L Unit I 1.1 Business and Politics 1.2 Politics of Cooperatives 1.3 Land Issues: Urban and Rural Political Parties 15 L Unit II 2.1 Indian National Congress (I), Nationalist Congress Party and BhartiyaJanata Party 2.2 Republican Party of India, Peasants and Workers Party , Shiv Sena and MaharshtraNavnirmanSena 2.3 Coalition Politics Peoples’ Movements in Maharashtra-I 15 L 3.1 Tribal Movements Unit III 3.2 Farmers Movements Peoples’ Movements in Maharashtra-II 15 L Unit IV 4.1 Movements for the Right to Information in Maharashtra 4.2 Initiatives for the Protection of Environment References: 1. Lele.Jayant, (1982). One Party Dominance in Maharashtra Resilience and Change, Mumbai: Popular Prakashan 2. -

Galaxy: International Multidisciplinary Research Journal the Criterion: an International Journal in English Vol

About Us: http://www.the-criterion.com/about/ Archive: http://www.the-criterion.com/archive/ Contact Us: http://www.the-criterion.com/contact/ Editorial Board: http://www.the-criterion.com/editorial-board/ Submission: http://www.the-criterion.com/submission/ FAQ: http://www.the-criterion.com/fa/ ISSN 2278-9529 Galaxy: International Multidisciplinary Research Journal www.galaxyimrj.com The Criterion: An International Journal in English Vol. 9, Issue-IV, August 2018 ISSN: 0976-8165 Contribution of Rationalist Social Reformer Gopal Ganesh Agarkar in Women Empowerment in Maharashtra Babasaheb Kisan Bhosale Asst. Professor, Changu Kana Thakur Arts, Commerce and Science College, New Panvel. Affiliated to University of Mumbai. Article History: Submitted-03/08/2018, Revised-06/09/2018, Accepted-10/09/2018, Published-15/09/2018. Abstract: Agarkar was a serious student of European enlightenment his rational methods to curb social issues altered the social reformation movement, his aimed at reforming inhuman traits of Hindu society, he aired his radical views in his periodical Sudharak in which he campaigned against the injustices and problems of women, he had to confront issues like the age of consent controversy, liberation of women, caste system, Sharada Sadan controversy, female feticide, Child marriage, polytheism, illiteracy. He propagated same education imparted to the boys and girls, he always tried to convince the Hindu society people what is just and appropriate for the well being of society. Keyword: Enlightenment, Empowerment, Persuade, Vicious Web, Polytheism, Female Feticide, Agreeable Age Introduction Gopal Ganesh Agarkar is held as one the foremost social reformers who sought for social transformation that entirely separates itself from worn-out customs, traditions as well as religious rituals; and believed to conduct all social dealings on the basis of individual liberty and intellectual assets. -

Idea of Emancipation and Discourse on Caste in Colonial Western India (Maharashtra)

Idea of Emancipation and Discourse on Caste in Colonial Western India (Maharashtra) Santosh Pandhari Suradkar Résumé L’idée d’émancipation et les discours sur les castes dans l’Inde occidentale coloniale (Maharashtra), denière partie partie du XIXème siècle. De vifs débats sur les castes eurent lieu à la fin du 19ème siècle Maharashtra entre les nationalistes, les mouvements des castes inférieures, les missionnaires britanniques, les orientalistes et les idéologues. Aussi, cette période dans le Maharashtra peut être caractérisée comme un âge d’ouverture des masses aux idées de démocratie, de liberté, d’égalité et de fraternité. La caste a toujours été au centre de la politique moderne indienne même si cette structure du pouvoir remonte à l’Inde médiévale. La caste fut exploitée en tant que principe central dans la distribution du pouvoir et des ressources matérielles durant la période coloniale. Mais dans le même temps, le colonialisme créa un espace démocratique et moderne; néanmoins cet espace fut monopolisé par les castes supérieures. La lutte nationaliste contre le pouvoir impérial avait alors pour but d’établir l’hégémonie de classe. Les mouvements des non-brahmanes et des basses castes, actifs pendant la période coloniale, avaient deux objectifs : une plus grande mobilité de caste-classe et l’éradiction du système de caste. Celui-ci joua un rôle important dans la détermination du contenu de la mobilisation politique et l’institutionnalisation de la démocratie moderne. La dynamique de caste et de classe reste la caractéristique de la complexité de la politique indienne. Le système de caste et le patriarcat brahmanique ont toujours travaillé de concert dans le maintien du système de caste et de la distribution inégale des ressources. -

Vinayak Damodar Savarkar - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Vinayak Damodar Savarkar - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 Vinayak Damodar Savarkar(28 May 1883 - 26 February 1966) Vinayak Damodar Savarkar (Marathi: ?????? ?????? ??????), was an Indian freedom fighter, revolutionary and politician. He was the proponent of liberty as the ultimate ideal. Savarkar was a poet, writer and playwright. He launched a movement for religious reform advocating dismantling the system of caste in Hindu culture, and reconversion of the converted Hindus back to Hindu religion. Savarkar created the term Hindutva, and emphasized its distinctiveness from Hinduism which he associated with social and political disunity. Savarkar’s Hindutva sought to create an inclusive collective identity. The five elements of Savarkar's philosophy were Utilitarianism, Rationalism and Positivism, Humanism and Universalism, Pragmatism and Realism. Savarkar's revolutionary activities began when studying in India and England, where he was associated with the India House and founded student societies including Abhinav Bharat Society and the Free India Society, as well as publications espousing the cause of complete Indian independence by revolutionary means. Savarkar published The Indian War of Independence about the Indian rebellion of 1857 that was banned by British authorities. He was arrested in 1910 for his connections with the revolutionary group India House. Following a failed attempt to escape while being transported from Marseilles, Savarkar was sentenced to two life terms amounting to 50 years' imprisonment and moved to the Cellular Jail in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. While in jail, Savarkar wrote the work describing Hindutva, openly espousing Hindu nationalism. -

POUTICAL BIOGRAPHY .Sayarkab

POUTICAL BIOGRAPHY .SAyARKAB . n3 CHAPTER V p o l i t i c a l BlQGRAPHy OF y ._ d .__s a v a b k a r (1883-1966) Early Childhood Vinayak Damodar Sava rice r »as born on 2Bth May, 1883 at Bhsgur in the Nasik District of Maharashtra (the then Bomhay Presidency). In his early days he cultivated the habit of reading, a variety of books mainly on history, 1 poetry and religion. It sharpened his reasoning powsr, moulded his poetic faculty and vetted his interest in history. In 1893 riots among Hindus and Muslims broke out every\»here in In d ie, especially in Bombay, Poona and Yeola in Maharashtra. Young Vinsyak was moved to read about the sufferings of Hindus and thought in a childlike way to avenge them by attacking the local mosques. This does not however, indicate the development of anti-Muslim attitude in him with a ll its seriousness. The last decade of the l9th century was the period of intense political agitation all over the country. Especially the Poona city was the centre of the national movement in Maharashtra. The people of the city had witnessed the remarkable sessions of the Indian National Congress and the controversial Social Conference. The celebrations of t I festivals in honour of Shlvaji, the Founder of Maratha Kingdom and Ganapatii a Hindu Deity) had helped to inculcate national feeling among the people. At the same time the people had been suffering repressioni injustice and humiliation at the hands of the B r it is h .