On the Presence of Genial Tubercles on the Mandible

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessment of Digital Panoramic Radiograph Magnification on Vertical Measurement Accuracy in Posterior Mandibular Regions

International Journal of Medical and Health Research Original Research Article International Journal of Medical and Health Research ISSN: 2454-9142; Impact Factor: RJIF 5.54 Received: 26-10-2018; Accepted: 28-11-2018 www.medicalsciencejournal.com Volume 4; Issue 12; December 2018; Page No. 184-186 Assessment of digital panoramic radiograph magnification on vertical measurement accuracy in posterior mandibular regions Dr. Kumar Gaurav Dubey1, Dr. Richa Dubey2 1 Senior Resident, Department of Dentistry, Anugrah Narayan Magadh Medical College and Hospital, Gaya, Bihar, India 2 Senior Resident, Department of Dentistry, Sri Krishna Medical College and Hospital, Muzaffarpur, Bihar, India * Corresponding Author: Dr. Richa Dubey Abstract Panoramic radiography is often the first choice method for the placement of implants because it provides information on the overall shape of the jaws, the position of the maxillary sinus floor and the nasal cavity floor, and the proximal distal as well as vertical position of the mandibular canal and the mental foramen. The measurements on digital radiography are quite acceptable and reliable for clinical use as long as the structures do not traverse the midline. Repeated measurements lead to a reduction in the systematic error and magnification to a loss of accuracy. The study was planned on the Department of Dentistry Anugrah Narayan Magadh Medical College and Hospital, Gaya.on 30 implants in the posterior mandibular regions. The digital panoramic radiographic images were taken using implants in the posterior mandibular regions. The digital panoramic radiographic equipment used. All digital panoramic radiographs were taken by technicians according to standard protocol provided by the manufacturer. This study is aimed to determine the accuracy of the vertical and horizontal measurements on digital panoramic radiographic images using implants in the posterior mandibular regions. -

Lab Manual Axial Skeleton Atla

1 PRE-LAB EXERCISES When studying the skeletal system, the bones are often sorted into two broad categories: the axial skeleton and the appendicular skeleton. This lab focuses on the axial skeleton, which consists of the bones that form the axis of the body. The axial skeleton includes bones in the skull, vertebrae, and thoracic cage, as well as the auditory ossicles and hyoid bone. In addition to learning about all the bones of the axial skeleton, it is also important to identify some significant bone markings. Bone markings can have many shapes, including holes, round or sharp projections, and shallow or deep valleys, among others. These markings on the bones serve many purposes, including forming attachments to other bones or muscles and allowing passage of a blood vessel or nerve. It is helpful to understand the meanings of some of the more common bone marking terms. Before we get started, look up the definitions of these common bone marking terms: Canal: Condyle: Facet: Fissure: Foramen: (see Module 10.18 Foramina of Skull) Fossa: Margin: Process: Throughout this exercise, you will notice bold terms. This is meant to focus your attention on these important words. Make sure you pay attention to any bold words and know how to explain their definitions and/or where they are located. Use the following modules to guide your exploration of the axial skeleton. As you explore these bones in Visible Body’s app, also locate the bones and bone markings on any available charts, models, or specimens. You may also find it helpful to palpate bones on yourself or make drawings of the bones with the bone markings labeled. -

Morphometric Analysis of Chin Shape in Inverted Mandible and Mid Symphysis Menti Angle

Dental Communication Biosc.Biotech.Res.Comm. Special Issue Vol 13 No 8 2020 Pp-104-107 Morphometric Analysis of Chin Shape in Inverted Mandible and Mid Symphysis Menti Angle Sachin Aditya B1 and Yuvaraj Babu K2* 1Saveetha Dental college and Hospitals, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Saveetha University, Chennai - 600077, India 2Assistant professor, Department of Anatomy, Saveetha Dental college and Hospitals, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Saveetha University, Chennai - 600077, India ABSTRACT In human anatomy, the skull 's facial skeleton, the outer surface of the mandible, is distinguished by a slight ridge in the median line, suggesting the mandibular symphysis or junction line in which the two lateral halves of the mandible usually unite at an early life (1-2 years). This is not a true symphysis, since there is no cartilage between the mandible's two hands. The main aim of the study is to measure the mid symphysis menti angle in the inverted aspect. 30 unsexed dry human skulls were taken from the Department of Anatomy, Saveetha Dental College and Hospital. Protractor was used to measure the mid symphysis menti angle in the inverted aspect of the mandible. The average measurement of mid symphysis menti angle was 76.16° and the shape of the mental protuberance for most of the samples were oval shaped. Our study has tried to analyse the mid symphysis menti angle and chin shape in the inverted aspect of mandibles, this data may be useful for surgeons in planning their surgery in the mandibular region. KEY WORDS: MID SYMPHYSIS MENTI ANGLE, MENtaL PROTUBERANCE, MANDIBLE, CHIN SHAPE. -

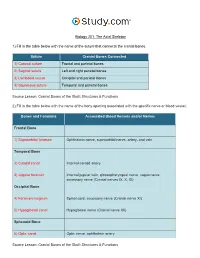

The Axial Skeleton Visual Worksheet

Biology 201: The Axial Skeleton 1) Fill in the table below with the name of the suture that connects the cranial bones. Suture Cranial Bones Connected 1) Coronal suture Frontal and parietal bones 2) Sagittal suture Left and right parietal bones 3) Lambdoid suture Occipital and parietal bones 4) Squamous suture Temporal and parietal bones Source Lesson: Cranial Bones of the Skull: Structures & Functions 2) Fill in the table below with the name of the bony opening associated with the specific nerve or blood vessel. Bones and Foramina Associated Blood Vessels and/or Nerves Frontal Bone 1) Supraorbital foramen Ophthalmic nerve, supraorbital nerve, artery, and vein Temporal Bone 2) Carotid canal Internal carotid artery 3) Jugular foramen Internal jugular vein, glossopharyngeal nerve, vagus nerve, accessory nerve (Cranial nerves IX, X, XI) Occipital Bone 4) Foramen magnum Spinal cord, accessory nerve (Cranial nerve XI) 5) Hypoglossal canal Hypoglossal nerve (Cranial nerve XII) Sphenoid Bone 6) Optic canal Optic nerve, ophthalmic artery Source Lesson: Cranial Bones of the Skull: Structures & Functions 3) Label the anterior view of the skull below with its correct feature. Frontal bone Palatine bone Ethmoid bone Nasal septum: Perpendicular plate of ethmoid bone Sphenoid bone Inferior orbital fissure Inferior nasal concha Maxilla Orbit Vomer bone Supraorbital margin Alveolar process of maxilla Middle nasal concha Inferior nasal concha Coronal suture Mandible Glabella Mental foramen Nasal bone Parietal bone Supraorbital foramen Orbital canal Temporal bone Lacrimal bone Orbit Alveolar process of mandible Superior orbital fissure Zygomatic bone Infraorbital foramen Source Lesson: Facial Bones of the Skull: Structures & Functions 4) Label the right lateral view of the skull below with its correct feature. -

Variation in Chin and Mandibular Symphysis Size and Shape in Males and Females: a CT-Based Study

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Variation in Chin and Mandibular Symphysis Size and Shape in Males and Females: A CT-Based Study Tatiana Sella Tunis 1,2,3,* , Israel Hershkovitz 1,2 , Hila May 1,2, Alexander Dan Vardimon 3, Rachel Sarig 2,3,4 and Nir Shpack 3 1 Department of Anatomy and Anthropology, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv 69978, Israel; [email protected] (I.H.); [email protected] (H.M.) 2 Dan David Center for Human Evolution and Biohistory Research, Shmunis Family Anthropology Institute, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv 69978, Israel; [email protected] 3 Department of Orthodontics, The Maurice and Gabriela Goldschleger School of Dental Medicine, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv 69978, Israel; [email protected] (A.D.V.); [email protected] (N.S.) 4 Department of Oral Biology, The Maurice and Gabriela Goldschleger School of Dental Medicine, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv 69978, Israel * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +972-3-640-7310 Received: 12 May 2020; Accepted: 11 June 2020; Published: 14 June 2020 Abstract: The chin is a unique anatomical landmark of modern humans. Its size and shape play an important role from the esthetic perspective. However, disagreement exists in the dental and anthropological literature regarding the sex differences in chin and symphysis morphometrics. The “sexual selection” theory is presented as a possible reason for chin formation in our species; however, many other contradictory theories also exist. -

Splanchnocranium

splanchnocranium - Consists of part of skull that is derived from branchial arches - The facial bones are the bones of the anterior and lower human skull Bones Ethmoid bone Inferior nasal concha Lacrimal bone Maxilla Nasal bone Palatine bone Vomer Zygomatic bone Mandible Ethmoid bone The ethmoid is a single bone, which makes a significant contribution to the middle third of the face. It is located between the lateral wall of the nose and the medial wall of the orbit and forms parts of the nasal septum, roof and lateral wall of the nose, and a considerable part of the medial wall of the orbital cavity. In addition, the ethmoid makes a small contribution to the floor of the anterior cranial fossa. The ethmoid bone can be divided into four parts, the perpendicular plate, the cribriform plate and two ethmoidal labyrinths. Important landmarks include: • Perpendicular plate • Cribriform plate • Crista galli. • Ala. • Ethmoid labyrinths • Medial (nasal) surface. • Orbital plate. • Superior nasal concha. • Middle nasal concha. • Anterior ethmoidal air cells. • Middle ethmoidal air cells. • Posterior ethmoidal air cells. Attachments The falx cerebri (slide) attaches to the posterior border of the crista galli. lamina cribrosa 1 crista galli 2 lamina perpendicularis 3 labyrinthi ethmoidales 4 cellulae ethmoidales anteriores et posteriores 5 lamina orbitalis 6 concha nasalis media 7 processus uncinatus 8 Inferior nasal concha Each inferior nasal concha consists of a curved plate of bone attached to the lateral wall of the nasal cavity. Each consists of inferior and superior borders, medial and lateral surfaces, and anterior and posterior ends. The superior border serves to attach the bone to the lateral wall of the nose, articulating with four different bones. -

When Anthropological Considerations Influence Our Attitude About the Chin and Orthognathic Surgery

DOI: 10.1051/odfen/2013205 J Dentofacial Anom Orthod 2013;16:305 Ó RODF / EDP Sciences When anthropological considerations influence our attitude about the chin and orthognathic surgery Mohamed EL-OKEILY, Masrour MAKAREMI ABSTRACT The presence of a chin is a specific and unique feature of the human face that is absent from the face of our hominid ancestors and all other primates. A number of anthropologists have studied this anthropomorphic characteristic and elaborated various theories concerning its genesis and anatomical usefulness. Recent research based on the analysis of stress using the finite element method (FEM) seems to establish that the presence of the chin is a biomechanical consequence of skeletal and muscular equilibrium peculiar to the human face. This data is an important addition to our matrix of thoughts that influences our attitude concerning the chin and orthognathic surgery. In particular, whether or not a genioplasty is necessary, and whether it should be performed separately from orthognathic surgery or at the same time. KEY WORDS Genioplasty Mentoplasty Chin Orthogathic surgery Anthopology of the chin INTRODUCTION The surgical correction of facial dyspla- these dysplasias requires a treatment plan sias is an important and growing multidisci- that involves close collaboration between plinary field today. Case management of the orthodontist and the maxillofacial Address for correspondence: Article received: 02-2013 El-Okeily M. Accepted for publication: 03-2013 Centre Bordelais 1 de Chirurgie Maxillo-Faciale 17, rue Esprit des Lois, 33000 Bordeaux [email protected] Article available at http://www.jdao-journal.org or http://dx.doi.org/10.1051/odfen/2013205 MOHAMED EL OKEILY ET MASROUR MAKAREMI two-fold objective that is both func- tional and morphological. -

Axial Skeleton 214 7.7 Development of the Axial Skeleton 214

SKELETAL SYSTEM OUTLINE 7.1 Skull 175 7.1a Views of the Skull and Landmark Features 176 7.1b Sutures 183 7.1c Bones of the Cranium 185 7 7.1d Bones of the Face 194 7.1e Nasal Complex 198 7.1f Paranasal Sinuses 199 7.1g Orbital Complex 200 Axial 7.1h Bones Associated with the Skull 201 7.2 Sex Differences in the Skull 201 7.3 Aging of the Skull 201 Skeleton 7.4 Vertebral Column 204 7.4a Divisions of the Vertebral Column 204 7.4b Spinal Curvatures 205 7.4c Vertebral Anatomy 206 7.5 Thoracic Cage 212 7.5a Sternum 213 7.5b Ribs 213 7.6 Aging of the Axial Skeleton 214 7.7 Development of the Axial Skeleton 214 MODULE 5: SKELETAL SYSTEM mck78097_ch07_173-219.indd 173 2/14/11 4:58 PM 174 Chapter Seven Axial Skeleton he bones of the skeleton form an internal framework to support The skeletal system is divided into two parts: the axial skele- T soft tissues, protect vital organs, bear the body’s weight, and ton and the appendicular skeleton. The axial skeleton is composed help us move. Without a bony skeleton, we would collapse into a of the bones along the central axis of the body, which we com- formless mass. Typically, there are 206 bones in an adult skeleton, monly divide into three regions—the skull, the vertebral column, although this number varies in some individuals. A larger number of and the thoracic cage (figure 7.1). The appendicular skeleton bones appear to be present at birth, but the total number decreases consists of the bones of the appendages (upper and lower limbs), with growth and maturity as some separate bones fuse. -

Skull / Cranium

Important! 1. Memorizing these pages only does not guarantee the succesfull passing of the midterm test or the semifinal exam. 2. The handout has not been supervised, and I can not guarantee, that these pages are absolutely free from mistakes. If you find any, please, report to me! SKULL / CRANIUM BONES OF THE NEUROCRANIUM (7) Occipital bone (1) Sphenoid bone (1) Temporal bone (2) Frontal bone (1) Parietal bone (2) BONES OF THE VISCEROCRANIUM (15) Ethmoid bone (1) Maxilla (2) Mandible (1) Zygomatic bone (2) Nasal bone (2) Lacrimal bone (2) Inferior nasalis concha (2) Vomer (1) Palatine bone (2) Compiled by: Dr. Czigner Andrea 1 FRONTAL BONE MAIN PARTS: FRONTAL SQUAMA ORBITAL PARTS NASAL PART FRONTAL SQUAMA Parietal margin Sphenoid margin Supraorbital margin External surface Frontal tubercle Temporal surface Superciliary arch Zygomatic process Glabella Supraorbital margin Frontal notch Supraorbital foramen Internal surface Frontal crest Sulcus for superior sagittal sinus Foramen caecum ORBITAL PARTS Ethmoidal notch Cerebral surface impresiones digitatae Orbital surface Fossa for lacrimal gland Trochlear notch / fovea Anterior ethmoidal foramen Posterior ethmoidal foramen NASAL PART nasal spine nasal margin frontal sinus Compiled by: Dr. Czigner Andrea 2 SPHENOID BONE MAIN PARTS: CORPUS / BODY GREATER WINGS LESSER WINGS PTERYGOID PROCESSES CORPUS / BODY Sphenoid sinus Septum of sphenoid sinus Sphenoidal crest Sphenoidal concha Apertura sinus sphenoidalis / Opening of sphenoid sinus Sella turcica Hypophyseal fossa Dorsum sellae Posterior clinoid process Praechiasmatic sulcus Carotid sulcus GREATER WINGS Cerebral surface • Foramen rotundum • Framen ovale • Foramen spinosum Temporal surface Infratemporalis crest Infratemporal surface Orbital surface Maxillary surface LESSER WINGS Anterior clinoid process Superior orbital fissure Optic canal PTERYGOID PROCESSES Lateral plate Medial plate Pterygoid hamulus Pterygoid fossa Pterygoid sulcus Scaphoid fossa Pterygoid notch Pterygoid canal (Vidian canal) Compiled by: Dr. -

Split Fracture and Displacement of Mandibular Lingual Cortical Plate of Mandibular Symphysis Requires Fixation Masaki Fujioka1*, Kenji Hayashida2 and Hiroto Saijo2

Fujioka et al. Trauma Cases Rev 2015, 1:4 ISSN: 2469-5777 Trauma Cases and Reviews Case Report: Open Access Split Fracture and Displacement of Mandibular Lingual Cortical Plate of Mandibular Symphysis Requires Fixation Masaki Fujioka1*, Kenji Hayashida2 and Hiroto Saijo2 1Clinical Professor, Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Nagasaki University, Nagasaki, Japan 2Staff surgeon, Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, National Hospital Organization Nagasaki Medical Center, Japan *Corresponding author: Masaki Fujioka, Clinical Professor, Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Nagasaki University, Nagasaki, and Director of the Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Clinical Research Center, National Hospital Organization Nagasaki Medical Center, Nagasaki, Japan, E-mail: [email protected] complaining of marked neck swelling and airway obstruction Abstract resulting from a car accident. As the patient had extensive oral The first priority in the management of comminuted mandibular bleeding, he immediately underwent intra-tracheal intubation. An fractures is the prevention of acute upper airway obstruction. emergent cerebral angiogram revealed extravasation of the mental Each division of mandibular fractures may cause respiratory artery; thus, transcatheter arterial embolization was performed. obstruction. Among the variety of such fractures, split fracture of the Computed tomography (CT) showed both maxillary and mandibular symphyseal lingual cortical plate has a significant influence on the oropharyngeal and laryngopharyngeal airway spaces, and causes open fractures (Figure 1a). The menton had fractured into pieces, a markedly restricted ventilatory function. As the bony fragment is pedicled to the geniohyoid and genioglossus muscles, this type of fracture restricts hyoid movements, which may result in disturbance of deglutition. We present two cases of split fracture and displacement of the mandibular lingual cortical plate of the mandibular symphysis, which were successfully treated with open reduction. -

Scrutiny of Four Conventional Visual Traits of Mandible for Sex Estimation in Indian Population

Open Access Austin Journal of Forensic Science and Criminology Special Article - Forensic Anthropology Scrutiny of Four Conventional Visual Traits of Mandible for Sex Estimation in Indian Population Vineeta Saini* Department of Forensic Medicine, Institute of Medical Abstract Sciences, India Population variability in the magnitude of the expression of sexual *Corresponding author: Vineeta Saini, Saini Sadan, dimorphism of various skeletal parts has been acknowledged by several Shri Hariom Shakti Ashram, Sector 12A, Gurgaon, anthropologists. Several morphological traits are in use for a long period for Haryana, India sex determination from mandible. In spite of quick and easy, these methods have been constantly criticized for the high rate of inter and intra observer error Received: July 05, 2017; Accepted: July 31, 2017; in sex classification. The present study investigates whether the traditional Published: August 29, 2017 visual parameters of human mandible are sexually dimorphic in North Indian population or it is just an old wive’s tale. A total of 189 adult mandibles (143 male and 46 females) of North Indian origin with age range 18 to 70 years collected from the Department of Forensic Medicine, IMS, BHU, and Varanasi. All pathological, fractured, deformed, or edentulous mandibles were excluded from the study. Four traditional morphological parameters of mandible (chin shape, gonial flaring, contour of lower border and muscular attachments) were carefully observed for sex discrimination. An inter and intra observer error test using Kohen’s Kappa was also calculated. It was observed that the contour of lower border and muscular attachments provided the lowest (62.96%) and the highest (83.59%) sexing accuracy respectively. -

Effects of Positions and Angulations of Titanium Dental Implants In

metals Article Effects of Positions and Angulations of Titanium Dental Implants in Biomechanical Performances in the All-on-Four Treatment: 3D Numerical and Strain Gauge Methods Aaron Yu-Jen Wu 1, Jui-Ting Hsu 2,3 , Lih-Jyh Fuh 2 and Heng-Li Huang 2,3,* 1 Department of Dentistry, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital & College of Medicine, Chang Gung University, 123, Ta-Pei Road, Niao-Sung, Kaohsiung 83305, Taiwan; [email protected] 2 School of Dentistry, China Medical University, 91 Hsueh-Shih Road, Taichung 40402, Taiwan; [email protected] (J.-T.H.); [email protected] (L.-J.F.) 3 Department of Bioinformatics and Medical Engineering, Asia University, 500, Lioufeng Rd., Wufeng, Taichung 41354, Taiwan * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-886-4-22053366 (ext. 2306); Fax: +1-886-4-22014043 Received: 30 December 2019; Accepted: 18 February 2020; Published: 21 February 2020 Abstract: In finite element (FE) simulations, the peak bone stresses were higher when loading with a cantilever extension (CE) than when loading without a CE by 33–49% in the cortical bone. In the in vitro experiments, the highest values of principal strain were all within the range of the minimum principal strain, and those peak bone strains were 40–58% greater when loading with a CE than when loading without a CE (p < 0.001). This study investigated how varying the implanted position and angulation of anterior implants in the All-on-Four treatment influenced the biomechanical environment in the alveolar bone around the dental implants. Ten numerical simulations of FE models and three in vitro samples of All-on-Four treatment of dental implants were created to investigate the effects of altering the implanted position and angulation type of anterior implants.