Articulated Definiteness Without Articles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Definiteness Determined by Syntax: a Case Study in Tagalog 1 Introduction

Definiteness determined by syntax: A case study in Tagalog1 James N. Collins Abstract Using Tagalog as a case study, this paper provides an analysis of a cross-linguistically well attested phenomenon, namely, cases in which a bare NP’s syntactic position is linked to its interpretation as definite or indefinite. Previous approaches to this phenomenon, including analyses of Tagalog, appeal to specialized interpretational rules, such as Diesing’s Mapping Hypothesis. I argue that the patterns fall out of general compositional principles so long as type-shifting operators are available to the gram- matical system. I begin by weighing in a long-standing issue for the semantic analysis of Tagalog: the interpretational distinction between genitive and nominative transitive patients. I show that bare NP patients are interpreted as definites if marked with nominative case and as narrow scope indefinites if marked with genitive case. Bare NPs are understood as basically predicative; their quantificational force is determined by their syntactic position. If they are syntactically local to the selecting verb, they are existentially quantified by the verb itself. If they occupy a derived position, such as the subject position, they must type-shift in order to avoid a type-mismatch, generating a definite interpretation. Thus the paper develops a theory of how the position of an NP is linked to its interpretation, as well as providing a compositional treatment of NP-interpretation in a language which lacks definite articles but demonstrates other morphosyntactic strategies for signaling (in)definiteness. 1 Introduction Not every language signals definiteness via articles. Several languages (such as Russian, Kazakh, Korean etc.) lack articles altogether. -

Logophoricity in Finnish

Open Linguistics 2018; 4: 630–656 Research Article Elsi Kaiser* Effects of perspective-taking on pronominal reference to humans and animals: Logophoricity in Finnish https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2018-0031 Received December 19, 2017; accepted August 28, 2018 Abstract: This paper investigates the logophoric pronoun system of Finnish, with a focus on reference to animals, to further our understanding of the linguistic representation of non-human animals, how perspective-taking is signaled linguistically, and how this relates to features such as [+/-HUMAN]. In contexts where animals are grammatically [-HUMAN] but conceptualized as the perspectival center (whose thoughts, speech or mental state is being reported), can they be referred to with logophoric pronouns? Colloquial Finnish is claimed to have a logophoric pronoun which has the same form as the human-referring pronoun of standard Finnish, hän (she/he). This allows us to test whether a pronoun that may at first blush seem featurally specified to seek [+HUMAN] referents can be used for [-HUMAN] referents when they are logophoric. I used corpus data to compare the claim that hän is logophoric in both standard and colloquial Finnish vs. the claim that the two registers have different logophoric systems. I argue for a unified system where hän is logophoric in both registers, and moreover can be used for logophoric [-HUMAN] referents in both colloquial and standard Finnish. Thus, on its logophoric use, hän does not require its referent to be [+HUMAN]. Keywords: Finnish, logophoric pronouns, logophoricity, anti-logophoricity, animacy, non-human animals, perspective-taking, corpus 1 Introduction A key aspect of being human is our ability to think and reason about our own mental states as well as those of others, and to recognize that others’ perspectives, knowledge or mental states are distinct from our own, an ability known as Theory of Mind (term due to Premack & Woodruff 1978). -

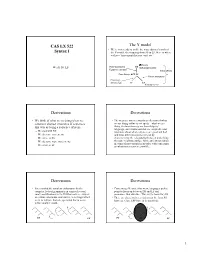

CAS LX 522 Syntax I the Y Model

CAS LX 522 The Y model • We’re now ready to tackle the most abstract branch of Syntax I the Y-model, the mapping from SS to LF. Here is where we have “movement that you can’t see”. θ Theory Week 10. LF Overt movement, DS Subcategorization Expletive insertion X-bar theory Case theory, EPP SS Covert movement Phonology/ Morphology PF LF Binding theory Derivations Derivations • We think of what we’re doing when we • The steps are not necessarily a reflection of what construct abstract structures of sentences we are doing online as we speak—what we are this way as being a sequence of steps. doing is characterizing our knowledge of language, and it turns out that we can predict our – We start with DS intuitions about what sentences are good and bad – We do some movements and what different sentences mean by – We arrive at SS characterizing the relationship between underlying – We do some more movements thematic relations, surface form, and interpretation in terms of movements in an order with constraints – We arrive at LF on what movements are possible. Derivations Derivations • It seems that the simplest explanation for the • Concerning SS, under this view, languages pick a complex facts of grammar is in terms of several point to focus on between DS and LF and small modifications to the DS that each are subject pronounce that structure. This is (the basis for) SS. to certain constraints, sometimes even things which • There are also certain restrictions on the form SS seem to indicate that one operation has to occur has (e.g., Case, EPP have to be satisfied). -

Minimal Pronouns, Logophoricity and Long-Distance Reflexivisation in Avar

Minimal pronouns, logophoricity and long-distance reflexivisation in Avar* Pavel Rudnev Revised version; 28th January 2015 Abstract This paper discusses two morphologically related anaphoric pronouns inAvar (Avar-Andic, Nakh-Daghestanian) and proposes that one of them should be treated as a minimal pronoun that receives its interpretation from a λ-operator situated on a phasal head whereas the other is a logophoric pro- noun denoting the author of the reported event. Keywords: reflexivity, logophoricity, binding, syntax, semantics, Avar 1 Introduction This paper has two aims. One is to make a descriptive contribution to the crosslin- guistic study of long-distance anaphoric dependencies by presenting an overview of the properties of two kinds of reflexive pronoun in Avar, a Nakh-Daghestanian language spoken natively by about 700,000 people mostly living in the North East Caucasian republic of Daghestan in the Russian Federation. The other goal is to highlight the relevance of the newly introduced data from an understudied lan- guage to the theoretical debate on the nature of reflexivity, long-distance anaphora and logophoricity. The issue at the heart of this paper is the unusual character of theanaphoric system in Avar, which is tripartite. (1) is intended as just a preview with more *The present material was presented at the Utrecht workshop The World of Reflexives in August 2011. I am grateful to the workshop’s audience and participants for their questions and comments. I am indebted to Eric Reuland and an anonymous reviewer for providing valuable feedback on the first draft, as well as to Yakov Testelets for numerous discussions of anaphora-related issues inAvar spanning several years. -

Definiteness and Determinacy

Linguistics and Philosophy manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Definiteness and Determinacy Elizabeth Coppock · David Beaver the date of receipt and acceptance should be inserted later Abstract This paper distinguishes between definiteness and determinacy. Defi- niteness is seen as a morphological category which, in English, marks a (weak) uniqueness presupposition, while determinacy consists in denoting an individual. Definite descriptions are argued to be fundamentally predicative, presupposing uniqueness but not existence, and to acquire existential import through general type-shifting operations that apply not only to definites, but also indefinites and possessives. Through these shifts, argumental definite descriptions may become either determinate (and thus denote an individual) or indeterminate (functioning as an existential quantifier). The latter option is observed in examples like `Anna didn't give the only invited talk at the conference', which, on its indeterminate reading, implies that there is nothing in the extension of `only invited talk at the conference'. The paper also offers a resolution of the issue of whether posses- sives are inherently indefinite or definite, suggesting that, like indefinites, they do not mark definiteness lexically, but like definites, they typically yield determinate readings due to a general preference for the shifting operation that produces them. Keywords definiteness · descriptions · possessives · predicates · type-shifting We thank Dag Haug, Reinhard Muskens, Luca Crniˇc,Cleo Condoravdi, Lucas -

8. Binding Theory

THE COMPLICATED AND MURKY WORLD OF BINDING THEORY We’re about to get sucked into a black hole … 11-13 March Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 2 OUR ROADMAP •Overview of Basic Binding Theory •Binding and Infinitives •Some cross-linguistic comparisons: Icelandic, Ewe, and Logophors •Picture NPs •Binding and Movement: The Nixon Sentences 3 SOME TERMINOLOGY • R-expression: A DP that gets its meaning by referring to an entity in the world. • Anaphor: A DP that obligatorily gets its meaning from another DP in the sentence. 1. Heidi bopped herself on the head with a zucchini. [Carnie 2013: Ch. 5, EX 3] • Reflexives: Myself, Yourself, Herself, Himself, Itself, Ourselves, Yourselves, Themselves • Reciprocals: Each Other, One Another • Pronoun: A DP that may get its meaning from another DP in the sentence or contextually, from the discourse. 2. Art said that he played basketball. [EX5] • “He” could be Art or someone else. • I/Me, You/You, She/Her, He/Him, It/It, We/Us, You/You, They/Them • Nominative/Accusative Pronoun Pairs in English • Antecedent: A DP that gives its meaning to another DP. • This is familiar from control; PRO needs an antecedent. Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 4 OBSERVATION 1: NO NOMINATIVE FORMS OF ANAPHORS • This makes sense, since anaphors cannot be subjects of finite clauses. 1. * Sheselfi / Herselfi bopped Heidii on the head with a zucchini. • Anaphors can be the subjects of ECM clauses. 2. Heidi believes herself to be an excellent cook, even though she always bops herself on the head with zucchini. SOME DESCRIPTIVE OBSERVATIONS Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. -

Degrees As Kinds Vs. Degrees As Numbers: Evidence from Equatives1 Linmin ZHANG — NYU Shanghai

Degrees as kinds vs. degrees as numbers: Evidence from equatives1 Linmin ZHANG — NYU Shanghai Abstract. Within formal semantics, there are two views with regard to the ontological status of degrees: the ‘degree-as-number’ view (e.g., Seuren, 1973; Hellan, 1981; von Stechow, 1984) and the ‘degree-as-kind’ view (e.g., Anderson and Morzycki, 2015). Based on (i) empirical distinctions between comparatives and equatives and (ii) Stevens’s (1946) theory on the four levels of measurements, I argue that both views are motivated and needed in accounting for measurement- and comparison-related meanings in natural language. Specifically, I argue that since the semantics of comparatives potentially involves measurable differences, comparatives need to be analyzed based on scales with units, on which degrees are like (real) numbers. In contrast, since equatives are typically used to convey the non-existence of differences, equa- tives can be based on scales without units, on which degrees can be considered kinds. Keywords: (Gradable) adjectives, Comparatives, Equatives, Similatives, Levels of measure- ments, Measurements, Comparisons, Kinds, Degrees, Dimensions, Scales, Units, Differences. 1. Introduction The notion of degrees plays a fundamental conceptual role in understanding measurements and comparisons. Within the literature of formal semantics, there are two major competing views with regard to the ontological status of degrees. For simplicity, I refer to these two ontologies as the ‘degree-as-number’ view and the ‘degree-as-kind’ view in this paper. Under the more canonical ‘degree-as-number’ view, degrees are considered primitive objects (of type d). Degrees are points on abstract totally ordered scales (see Seuren, 1973; Hellan, 1981; von Stechow, 1984; Heim, 1985; Kennedy, 1999). -

Anaphoric Reference to Propositions

ANAPHORIC REFERENCE TO PROPOSITIONS A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Todd Nathaniel Snider December 2017 c 2017 Todd Nathaniel Snider ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ANAPHORIC REFERENCE TO PROPOSITIONS Todd Nathaniel Snider, Ph.D. Cornell University 2017 Just as pronouns like she and he make anaphoric reference to individuals, English words like that and so can be used to refer anaphorically to a proposition introduced in a discourse: That’s true; She told me so. Much has been written about individual anaphora, but less attention has been paid to propositional anaphora. This dissertation is a com- prehensive examination of propositional anaphora, which I argue behaves like anaphora in other domains, is conditioned by semantic factors, and is not conditioned by purely syntactic factors nor by the at-issue status of a proposition. I begin by introducing the concepts of anaphora and propositions, and then I discuss the various words of English which can have this function: this, that, it, which, so, as, and the null complement anaphor. I then compare anaphora to propositions with anaphora in other domains, including individual, temporal, and modal anaphora. I show that the same features which are characteristic of these other domains are exhibited by proposi- tional anaphora as well. I then present data on a wide variety of syntactic constructions—including sub- clausal, monoclausal, multiclausal, and multisentential constructions—noting which li- cense anaphoric reference to propositions. On the basis of this expanded empirical do- main, I argue that anaphoric reference to a proposition is licensed not by any syntactic category or movement but rather by the operators which take propositions as arguments. -

A Syntactic Analysis of Rhetorical Questions

A Syntactic Analysis of Rhetorical Questions Asier Alcázar 1. Introduction* A rhetorical question (RQ: 1b) is viewed as a pragmatic reading of a genuine question (GQ: 1a). (1) a. Who helped John? [Mary, Peter, his mother, his brother, a neighbor, the police…] b. Who helped John? [Speaker follows up: “Well, me, of course…who else?”] Rohde (2006) and Caponigro & Sprouse (2007) view RQs as interrogatives biased in their answer set (1a = unbiased interrogative; 1b = biased interrogative). In unbiased interrogatives, the probability distribution of the answers is even.1 The answer in RQs is biased because it belongs in the Common Ground (CG, Stalnaker 1978), a set of mutual or common beliefs shared by speaker and addressee. The difference between RQs and GQs is thus pragmatic. Let us refer to these approaches as Option A. Sadock (1971, 1974) and Han (2002), by contrast, analyze RQs as no longer interrogative, but rather as assertions of opposite polarity (2a = 2b). Accordingly, RQs are not defined in terms of the properties of their answer set. The CG is not invoked. Let us call these analyses Option B. (2) a. Speaker says: “I did not lie.” b. Speaker says: “Did I lie?” [Speaker follows up: “No! I didn’t!”] For Han (2002: 222) RQs point to a pragmatic interface: “The representation at this level is not LF, which is the output of syntax, but more abstract than that. It is the output of further post-LF derivation via interaction with at least a sub part of the interpretational component, namely pragmatics.” RQs are not seen as syntactic objects, but rather as a post-syntactic interface phenomenon. -

Bare Nouns, Incorporation, and Scope*

The Proceedings of AFLA 16 BARE NOUNS, INCORPORATION, AND SCOPE* Ileana Paul University of Western Ontario [email protected] This paper questions the connection between bare nouns, incorporation and obligatory narrow scope. Data from Malagasy show that bare nouns take variable scope (wide and narrow) despite being pseudo-incorporated. The resulting typology of incorporation is presented and two analyses of the Malagasy data are explored. The paper concludes with a discussion of the nature of incorporation and indefiniteness. 1. Introduction This paper considers the following question: what is the connection between bare nouns, incorporation, and narrow scope? This question is a natural one to ask because in the literature there are many examples of bare nouns and incorporated nouns taking obligatory narrow scope. Data from Malagasy, however, show that bare nouns can take wide scope, despite being bare and despite being pseudo-incorporated. These data therefore call into question the connection between the syntax of nouns (bareness, incorporation) and their semantics (scope). More broadly, the scope facts of Malagasy bare nouns show us that the mapping between syntax and semantics is not as uniform as one might have expected. The outline of this paper is as follows: in section 2, I illustrate the basic distribution of bare nouns in Malagasy and section 3 provides evidence for pseudo-incorporation (Massam 2001). In section 4, I show that bare nouns can take variable scope (narrow and wide) and in sections 5 and 6 I discuss some of the theoretical implications of the data. Section 7 concludes. 2. Malagasy Bare Nouns Malagasy is an Austronesian language spoken in Madagascar; the dominant word order is VOS. -

Minimal Pronouns1

1 Minimal Pronouns1 Fake Indexicals as Windows into the Properties of Bound Variable Pronouns Angelika Kratzer University of Massachusetts at Amherst June 2006 Abstract The paper challenges the widely accepted belief that the relation between a bound variable pronoun and its antecedent is not necessarily submitted to locality constraints. It argues that the locality constraints for bound variable pronouns that are not explicitly marked as such are often hard to detect because of (a) alternative strategies that produce the illusion of true bound variable interpretations and (b) language specific spell-out noise that obscures the presence of agreement chains. To identify and control for those interfering factors, the paper focuses on ‘fake indexicals’, 1st or 2nd person pronouns with bound variable interpretations. Following up on Kratzer (1998), I argue that (non-logophoric) fake indexicals are born with an incomplete set of features and acquire the remaining features via chains of local agreement relations established in the syntax. If fake indexicals are born with an incomplete set of features, we need a principled account of what those features are. The paper derives such an account from a semantic theory of pronominal features that is in line with contemporary typological work on possible pronominal paradigms. Keywords: agreement, bound variable pronouns, fake indexicals, meaning of pronominal features, pronominal ambiguity, typologogy of pronouns. 1 . I received much appreciated feedback from audiences in Paris (CSSP, September 2005), at UC Santa Cruz (November 2005), the University of Saarbrücken (workshop on DPs and QPs, December 2005), the University of Tokyo (SALT XIII, March 2006), and the University of Tromsø (workshop on decomposition, May 2006). -

Situations and Individuals

Forthcoming with MIT Press Current Studies in Linguistics Summer 2005 Situations and Individuals Paul Elbourne To my father To the memory of my mother Preface This book deals with the semantics of the natural language expressions that have been taken to refer to individuals: pronouns, definite descriptions and proper names. It claims, contrary to previous theorizing, that they have a common syntax and semantics, roughly that which is currently associated by philosophers and linguists with definite descriptions as construed in the tradition of Frege. As well as advancing this proposal, I hope to achieve at least one other aim, that of urging linguists and philosophers dealing with pronoun interpretation, in particular donkey anaphora, to consider a wider range of theories at all times than is sometimes done at present. I am thinking particularly of the gulf that seems to have emerged between those who practice some version of dynamic semantics (including DRT) and those who eschew this approach and claim that the semantics of donkey pronouns crucially involves definite descriptions (if they consider donkey anaphora at all). In my opinion there is too little work directly comparing the claims of these two schools (for that is what they amount to) and testing them against the data in the way that any two rival theories might be tested. (Irene Heim’s 1990 article in Linguistics and Philosophy does this, and largely inspired my own project, but I know of no other attempts.) I have tried to remedy that in this book. I ultimately come down on the side of definite descriptions and against dynamic semantics; but that preference is really of secondary importance beside the attempt at a systematic comparative project.