Around the Moon in 28 Days: Lunar Observing for Beginners

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue #1 – 2012 October

TTSIQ #1 page 1 OCTOBER 2012 Introducing a new free quarterly newsletter for space-interested and space-enthused people around the globe This free publication is especially dedicated to students and teachers interested in space NEWS SECTION pp. 3-22 p. 3 Earth Orbit and Mission to Planet Earth - 13 reports p. 8 Cislunar Space and the Moon - 5 reports p. 11 Mars and the Asteroids - 5 reports p. 15 Other Planets and Moons - 2 reports p. 17 Starbound - 4 reports, 1 article ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ARTICLES, ESSAYS & MORE pp. 23-45 - 10 articles & essays (full list on last page) ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- STUDENTS & TEACHERS pp. 46-56 - 9 articles & essays (full list on last page) L: Remote sensing of Aerosol Optical Depth over India R: Curiosity finds rocks shaped by running water on Mars! L: China hopes to put lander on the Moon in 2013 R: First Square Kilometer Array telescopes online in Australia! 1 TTSIQ #1 page 2 OCTOBER 2012 TTSIQ Sponsor Organizations 1. About The National Space Society - http://www.nss.org/ The National Space Society was formed in March, 1987 by the merger of the former L5 Society and National Space institute. NSS has an extensive chapter network in the United States and a number of international chapters in Europe, Asia, and Australia. NSS hosts the annual International Space Development Conference in May each year at varying locations. NSS publishes Ad Astra magazine quarterly. NSS actively tries to influence US Space Policy. About The Moon Society - http://www.moonsociety.org The Moon Society was formed in 2000 and seeks to inspire and involve people everywhere in exploration of the Moon with the establishment of civilian settlements, using local resources through private enterprise both to support themselves and to help alleviate Earth's stubborn energy and environmental problems. -

The Lunar Economy - Years 1-25 Dec 1986 - Nov 2011

MMM Theme Issues: The Lunar Economy - Years 1-25 Dec 1986 - Nov 2011 The Moon Would Seem to be a Tough Nut to Crack Until we look Closer At first we may not be able to produce “first choice” alloys and other building and manufacturing materials, but what we can produce early on will be adequate to substitute for enough products that the gross tonnage of imports from Earth can be cut to a fraction. Power Generation is essential. Better, as we point out in Foundation 2 above, the Moon has the real estate advantage of “location, location, location.” As a result, anything produced on the Moon could be shipped to space facilities in Low Earth Orbit (LEO) and Geosynchronous Orbit (GEO) at a cost advantage of equivalent products manufactured on Earth. Thus the cost of importing to the Moon those things that cannot yet be manufactured there, could be ofset by exports of Lunar manufactured goods and materials to markets in LEO and GEO. Production of consumer goods will be important and enterprise will be a key factor. It will take time, but financial break-even is possible in time. The obstacles are great. But once you look closely at the options, these obstacles fall in the ranks of those that faced MMM Theme Issues: The Lunar Economy - Years 1-25 Dec 1986 - Nov 2011 pioneers of other frontiers on Earth in eras gone by. Establishing and then elaborating the roots and possibilities of a lunar economy sufcient to support permanent pioneer frontier settlements are there, and treating them one by one has been a major theme of Moon Miners’ Manifesto through the years. -

Complete Dissertation

VU Research Portal The lunar crust Martinot, Melissa 2019 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Martinot, M. (2019). The lunar crust: A study of the lunar crust composition and organisation with spectroscopic data from the Moon Mineralogy Mapper. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 10. Oct. 2021 VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT THE LUNAR CRUST A study of the lunar crust composition and organisation with spectroscopic data from the Moon Mineralogy Mapper ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor of Philosophy aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. V. Subramaniam, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van de promotiecommissie van de Faculteit der Bètawetenschappen op maandag 7 oktober 2019 om 13.45 uur in de aula van de universiteit, De Boelelaan 1105 door Mélissa Martinot geboren te Die, Frankrijk promotoren: prof.dr. -

Lunar Program Observing List Lunar Observing Program Coordinator: Nina Chevalier 1662 Sand Branch Rd

Lunar Program Observing List Lunar Observing Program Coordinator: Nina Chevalier 1662 Sand Branch Rd. Bigfoot, Texas 78005 210-218-6288 [email protected] The List The 100 features to be observed for the Lunar Program are listed below. At the top of each section is a space to list the instruments used in the program. After that are five columns: CHK, Object, Feature, Date and Time. The "CHK" column should be used to check off the feature as you observe it. The "Object" column lists the features in Naked Eye, Binocular, and Telescopic order, and tells you what you are observing and when the best time is to observe it. The "Feature" column lists the 100 features to be observed. Finally, the "Date" and "Time" columns allow you to log when you observed the objects. In the last section, we have listed the 10 optional activities, and broken them down as to naked eye, binocular, and telescopic. Also on page 4, we have included four illustrations to help with observing four of the naked eye features. We certainly hope that you find the Lunar Program useful in helping you become more familiar with earth's nearest neighbor. If after completing this program you would like to do more work in this area, you may contact The Association of Lunar and Planetary Observers. Julius L. Benton Jr. ALPO Lunar Recorder % Associates in Astronomy 305 Surrey Road Savannah, Ga. 31410 (912) 897-0951 E-mail: [email protected]. Until then, good luck, clear skies, and good observing. Lunar Program Checklist Naked Eye Objects Instruments Used ____________________________ -

Moon Course Section 27-33 V1.0

Around the Moon in 28 Days: Lunar Observing for Beginners Course Notes Section 27 - Lunar Day 22 Section 28 - Lunar Day 23 Section 29 - Lunar Day 24 Section 30 - Lunar Day 25 Section 31 - Lunar Day 26 Section 32 - Lunar Day 27 Section 33 - Lunar Day 28 (The End) Copyright © 2010 Mintaka Publishing Inc. 2 Section 27 - Lunar Day 22 Tonight's late rising Moon might seem impossible to study when you have a daytime work schedule, but why not consider going to bed early and spending the early morning hours contemplating some lunar history and the peace and quiet before the day begins? Let's journey off to the lonely Riphaeus Mountains just southwest of crater Copernicus. Northeast of the range is another smooth floored area on the border of Oceanus Procellarum. It is here that Surveyor 3 landed on April 19, 1967. Figure 27-1: The major features of the Moon on Day 22 Around the Moon in 28 Days: Lunar Observing for Beginners 3 Figure 27-2: Surveyor 3 and Apollo 12 and 14 landing sites (courtesy of NASA) After bouncing three times, the probe came to rest on a smooth slope in a sub-telescopic crater. As its on-board television monitors watched, Surveyor 3 extended its mechanical arm with a "first of its kind" miniature shovel and dug to a depth of 18 inches. The view of sub-soil material and its clean-cut lines allowed scientists to conclude that the loose lunar soil could compact. Watching Surveyor 3 pound its shovel against the surface, the resulting tiny "dents" answered the crucial question. -

NASA MEO Lunar Impact Candidates

NASA Marshall Space Flight Center - Automated Lunar and Meteor Observatory (ALaMO) - Candidate lunar impact observation database Last Updated: 1-May-2008 By: D. Moser PRELIMINARY # of video Lunar Effective Probable Lunar Lunar frames Lunar elevation Aperture focal length MSFC Flash # Date (UT) Peak (UT) Type longitude latitude Region (1/30 sec) phase (deg) (cm) Optical config. (cm) Camera Digitizer Location Observers Press release links 1 7-Nov-05 11:41:52 Taurid 39.5 W 31.9 N Mare Imbrium 5 0.38 wax 28.4 25.4 Newtonian T 119 StellaCam EX Sony GV-D800 MSFC 4487 Suggs and Swift http://science.nasa.gov/headlines/y2005/22dec_lunartaurid.htm 2 2-May-06 02:34:40.08 Sporadic 19.6 W 24.3 S Bullialdus 14 0.21 wax 26.1 25.4 Newtonian T 119 StellaCam EX Sony GV-D800 MSFC ALAMO Moser and McNamara http://science.nasa.gov/headlines/y2006/13jun_lunarsporadic.htm 3 4-Jun-06 04:48:35.367 Sporadic 35.8 W 11.8 S Rima Herigonius 1.5 0.52 wax 18.9 25.4 Newtonian T 119 StellaCam EX Sony GV-D800 MSFC ALAMO Swift, Hollon, & Altstatt 4 21-Jun-06 08:57:17.5 Sporadic 62.2 E 13.9 N Mare Crisium 2.5 0.21 wan 19.7 25.4 Newtonian T 119 StellaCam EX Sony GV-D800 MSFC ALAMO Moser and McNamara 4 " " " " " " 1.5 " " 35.5 Rit Chret SD 94 StellaCam EX Sony GV-D800 MSFC ALAMO Suggs 5 19-Jul-06 10:14:44 Sporadic 60 E 23 N Mare Crisium 1 0.32 wan 51.2 25.4 Newtonian T 119 StellaCam EX Sony GV-D800 MSFC ALAMO Suggs 5 " " " " " " 2 " " 35.5 Rit Chret SD 94 StellaCam EX Sony GV-D800 MSFC ALAMO Moser 6 3-Aug-06 01:43:19 Sporadic 38 W 26 N Aristarchus 3.5 0.47 wax 27.8 35.5 Rit -

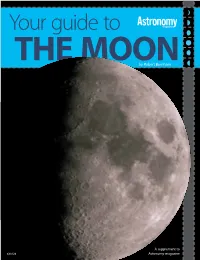

Guide to Observing the Moon

Your guide to The Moonby Robert Burnham A supplement to 618128 Astronomy magazine 4 days after New Moon south is up to match the view in a the crescent moon telescope, and east lies to the left. f you look into the western sky a few evenings after New Moon, you’ll spot a bright crescent I glowing in the twilight. The Moon is nearly everyone’s first sight with a telescope, and there’s no better time to start watching it than early in the lunar cycle, which begins every month when the Moon passes between the Sun and Earth. Langrenus Each evening thereafter, as the Moon makes its orbit around Earth, the part of it that’s lit by the Sun grows larger. If you look closely at the crescent Mare Fecunditatis zona I Moon, you can see the unlit part of it glows with a r a ghostly, soft radiance. This is “the old Moon in the L/U. p New Moon’s arms,” and the light comes from sun- /L tlas Messier Messier A a light reflecting off the land, clouds, and oceans of unar Earth. Just as we experience moonlight, the Moon l experiences earthlight. (Earthlight is much brighter, however.) At this point in the lunar cycle, the illuminated Consolidated portion of the Moon is fairly small. Nonetheless, “COMET TAILS” EXTENDING from Messier and Messier A resulted from a two lunar “seas” are visible: Mare Crisium and nearly horizontal impact by a meteorite traveling westward. The big crater Mare Fecunditatis. Both are flat expanses of dark Langrenus (82 miles across) is rich in telescopic features to explore at medium lava whose appearance led early telescopic observ- and high magnification: wall terraces, central peaks, and rays. -

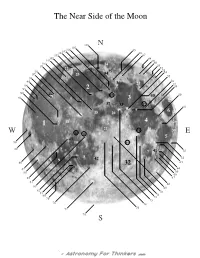

A Map of the Visible Side of the Moon

The Near Side of the Moon 108 N 107 106 105 45 104 46 103 47 102 48 101 49 100 24 50 99 51 52 22 53 98 33 35 54 97 34 23 55 96 95 56 36 25 57 94 58 93 2 92 44 15 40 59 91 3 27 37 17 38 60 39 6 19 20 26 28 1 18 4 29 21 11 30 W 12 E 14 5 43 90 10 16 89 7 41 61 8 62 9 42 88 32 63 87 64 86 31 65 66 85 67 84 68 83 69 82 81 70 80 71 79 72 73 78 74 77 75 76 S Maria (Seas) Craters 1 - Oceanus Procellarum (Ocean of Storms) 45 - Aristotles 77 - Tycho 2 - Mare Imbrium (Sea of Showers) 46 - Cassini 78 - Pitatus 3 - Mare Serenitatis (Sea of Serenity) 47 - Eudoxus 79 - Schickard 4 - Mare Tranquillitatis (Sea of Tranquility) 48 - Endymion 80 - Mercator 5 - Mare Fecunditatis (Sea of Fertility) 49 - Hercules 81 - Campanus 6 - Mare Crisium (Sea of Crises) 50 - Atlas 82 - Bulliadus 7 - Mare Nectaris (Sea of Nectar) 51 - Mercurius 83 - Fra Mauro 8 - Mare Nubium (Sea of Clouds) 52 - Posidonius 84 - Gassendi 9 - Mare Humorum (Sea of Moisture) 53 - Zeno 85 - Euclides 10 - Mare Cognitum (Known Sea) 54 - Menelaus 86 - Byrgius 18 - Mare Insularum (Sea of Islands) 55 - Le Monnier 87 - Billy 19 - Sinus Aestuum (Bay of Seething) 56 - Vitruvius 88 - Cruger 20 - Mare Vaporum (Sea of Vapors) 57 - Cleomedes 89 - Grimaldi 21 - Sinus Medii (Bay of the Center) 58 - Plinius 90 - Riccioli 22 - Sinus Roris (Bay of Dew) 59 - Magelhaens 91 - Galilaei 23 - Sinus Iridum (Bay of Rainbows) 60 - Taruntius 92 - Encke T 24 - Mare Frigoris (Sea of Cold) 61 - Langrenus 93 - Eddington 25 - Lacus Somniorum (Lake of Dreams) 62 - Gutenberg 94 - Seleucus 26 - Palus Somni (Marsh of Sleep) -

Geofizikai Közlemények

A MAGYAR ÁLLAMI EÖTVÖS LORÁND GEOFIZIKAI INTÉZET KIADVÁNYA GEOFIZIKAI KÖZLEMÉNYEK A MAGYAR GEOFIZIKUSOK EGYESÜLETÉNEK HIVATALOS LAPJA * SZERKESZTI : DOMB AI TIBOR VI. KÖTET 3 — 4. SZÁM MŰSZAKI KÖNYVKIADÓ BUDAPEST 195 7 Felelős szerkesztő: DOMBAI TIBOR Szerkesztőbizottság : Dr. BARTA GYÖRGY, Dr. EGYED LÁSZLÓ, Dr. FACSINAY LÁSZLÓ, KILCZER GYULA, OSZLACZKY SZILÁRD Szerkesztő: B U D AY TIBO R Felelős kiadó: Solt Sándor Műszaki szerkesztő: ívterjedelem: 3 és fél B/5 (5 A/5) Megrendelve: 1957. XI. 1. Hegedűs Ernő Ábrák száma: 33 db. Imprimálva: 1957. XII. 15 Papíralak: 70x100 Példányszám: 700 Megjelent: 1957. XII. 31. Azonossági szám: 40 170 Ez a könyv a MNOSZ 5601-54 és 5602-54. A szabványok szerint készült. 15302. Franklin-nyomda Budapest, VIII., Szentkirályi utca 28. Felelős: Vértes Ferenc. L. E G Y E D THE MAGNETIC FIELD AND. THE INTERNAL STRUCTURE OF THE EARTH The paper presents a possible explanation for the dipole field of the Earth on the basis of the momentum of oriented nuclei in the inner core. Furthermore, it is shown that the cause of the westerly drift of the dipole field, isoporic foci and non dipole field may be referred to the expansion of the mantle and core of the Earth, causing also currents in the outer core. A FÖLDI MÁGNESES TÉR KAPCSOLATA A FÖLD BELSŐ SZERKEZETÉVEL EGYED LÁSZLÓ A Föld belső szerkezetének kérdésével párhuzamosan felvetődik a földi mágnesség eredete is. A földi mágnesség problémája kezdetben könnyebbnek látszott, mint mai ismereteink szerint. A Föld vasmagos modelljéből kézenfekvőén következett a mágneses tér eredetének az a magyarázata, hogy a mágneses tér állandó részének a forrása ez a vas- tömeg. -

AL Lunar 100

AL Lunar 100 The AL Lunar 100 introduces amateur astronomers to that object in the sky that most of us take for granted, and which deep sky observers have come to loathe. But even though deep sky observers search for dark skies (when the moon is down), this list gives them something to do when the moon is up. In other words, it gives us something to observe the rest of the month, and we all know that the sky is always clear when the moon is up. The AL Lunar 100 also allows amateurs in heavily light polluted areas to participate in an observing program of their own. This list is well suited for the young, inexperienced observer as well as the older observer just getting into our hobby since no special observing skills are required. It is well balanced because it develops naked eye, binocular, and telescopic observing skills. The AL Lunar 100 consists of 100 features on the moon. These 100 features are broken down into three groups: 18 naked eye, 46 binocular, and 36 telescopic features. Any pair of binoculars and any telescope may be used for this list. This list does not require expensive equipment. Also, if you have problems with observing the features at one level, you may go up to the next higher level. In other words, if you have trouble with any of the naked eye objects, you may jump up to binoculars. If you have trouble with any of the binocular objects, then you may move up to a telescope. Before moving up to the next higher level, please try to get as many objects as you can with the instrument required at that level. -

Beware of the 'Siren Call' to Lunar Polar Water Ice!

Beware of the ‘siren call’ to lunar polar water ice! INGREDIENTS: Water, Hydrogen Sulfide, Ammonia, Sulfur Dioxide, Ethylene, Carbon Dioxide, Methanol, Methane, Hydroxide PSR water ice (“∼3.5% of cold traps exhibit ice exposures”, Li et al., 2018) What lies below 1 m??? (i.e., Siegler et al., 2016, ice stability depths) Geotechnical properties??? Hayne, et al. 2015 Fisher, et al. 2017 Sanin, et al. 2017 Resources Galore! Pyroclastic Glass Titanium KREEP Start simple: FeTiO3+H2 ---->Fe+TiO2+H2O Modeled A Scientific Bonanza! Mare Ages Lunar Science for Landed Missions Workshop Findings Report https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2018EA000490 Marius Pit Reiner Gamma Marius Hills Wanted Lunar Outpost at Aristarchus based on 1:5M USGS Plateau geological maps and Single lunar field-station Wilhelms, 1987 looking for a long-term Within 100 km relationship with a Herodotus, Aristarchus craters, Aristarchus dependable, trustworthy Plateau (lavas and ash), Vallis Schröteri power generation unit. Within 250 km Prinz, Krieger, Wollaston craters, Montes Nuclear doesn’t scare me. Harbinger, Montes Agricola, Prinz rilles, [email protected] Oceanus Procellarum Within 500 km Marius, Brayley, Diophantus, Delisle, Angstrom, Gruithusien, Schiaparelli, craters, Marius Hills, Rima Marius, Gruithusien domes, late Imbrium lava flows Within 750 km Kepler, Euler, Mairan, Sharp, Lavoisier A, Lichtenberg, Briggs, Seleucus, Russell, Struve, Be careful of the allure Eddington, Galilaei, Reiner craters, Reiner Gamma swirls, Rümker Plateau, Mare 250 km to ‘perpetual sunlight’! Imbrium, young lavas near Lichtenberg Within 1000 km 500 km Cavalerius, Hevelius, Encke, Hortensius, Copernicus, Pytheas, Lambert, Bianchini, Bouguer, Harpalus, Markov, Harding, Krafft, 750 km Cardanus craters, Sinus Iridium, Sinus Roris, Montes Jura, Montes Carpatus, Flamsteed ring mare, Hortensius domes, feldspathic 1000 km highlands. -

FEATURE DATE TIME SEEING TRANSP. LATITUDE LONGITUDE Naked-Eye Objects E, VG, G, F, P 1 (Worst) to (Within 72 Hrs of New) 6 (Best)

Astronomical League Lunar checkist X FEATURE DATE TIME SEEING TRANSP. LATITUDE LONGITUDE Naked-Eye Objects E, VG, G, F, P 1 (worst) to (Within 72 Hrs of new) 6 (best) [ ] Old Moon in New Moon's Arms _______ ______ _______ ______ ____________________________ ____________________________ [ ] New Moon in Old Moon's Arms _______ ______ _______ ______ ____________________________ ____________________________ (Within 40 Hrs of new) [ ] Crescent Moon, Waxing _______ ______ _______ ______ ____________________________ ____________________________ [ ] Crescent Moon, Waning _______ ______ _______ ______ ____________________________ ____________________________ (When full) [ ] Man in the Moon _______ ______ _______ ______ ____________________________ ____________________________ [ ] Woman in the Moon _______ ______ _______ ______ ____________________________ ____________________________ [ ] Rabbit in the Moon _______ ______ _______ ______ ____________________________ ____________________________ (When gibbous) [ ] Cow Jumping Over the Moon _______ ______ _______ ______ ____________________________ ____________________________ Maria [ ] Crisium _______ ______ _______ ______ ____________________________ ____________________________ [ ] Fecunditatis _______ ______ _______ ______ ____________________________ ____________________________ [ ] Serenitatis _______ ______ _______ ______ ____________________________ ____________________________ [ ] Tranquillitatis _______ ______ _______ ______ ____________________________ ____________________________ [ ] Nectaris