Niger Vulnerability Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regional Meningitis Surveillance Information Bulletin Situation End of Week 19 (05 to 11.05.03) Date of Report: 24.05.2003 Highlights

World Health Organization - Multi-Disease Surveillance Centre Ouagadougou Regional Meningitis Surveillance Information bulletin_ Situation end of Week 19 (05 to 11.05.03) Date of report: 24.05.2003 Highlights: S Niger : 42 Nm W135 isolated in Niger from week 1 to 18, 2003 in 5 regions out of 8 By regions : Dosso (9), Niamey (15), Tahoua (12), Tillaberi (4) and Zinder (2) S Decreasing trend in all reporting countries Number of Cases and Deaths of Suspected Meningitis Reported to WHO by Countries of the African Meningitis Belt and pathogens identifieda. January 1 - May 11 (Week 19), 2003. Country Reporting Cases Deaths CFR No Nm positive Observations (Epidemic Districts) weeks % Beninb W1 - W19 350 76 21.7 2 Nm W135c Vaccination done in two (None) 6 Nm Ad districts (Tangieta, Toucountouna) Burkina Faso W1 - W19 7,417 1,104 14.9 264 Nm A Laboratory results until week (none) 104 Nm W135 18 Chad W1 – W16 468 72 15.4 N/A No cases week 16 (None) Ghana W1 - W19 1,399 177 12.6 8 Nm A in Bole (None) 11 Nm A in Maprusi 7 Nm A in WA 2 W135 found in none epidemic area Mali W1 - W18 723 49 6.8 16 Nm A No circle in alert (none) 11 Nm W135e Lab results until wekk13 to be cross-checked Niger W1 - W19 7.029 566 8.05 346 Nm A 3 districts still in alert (Magaria,Matameye) 42 Nm W135f Matameye, Magaria, Aguie Significant under reporting. On going CSM activity in Yobbe State but no data available up to date. -

Niger Country Brief: Property Rights and Land Markets

NIGER COUNTRY BRIEF: PROPERTY RIGHTS AND LAND MARKETS Yazon Gnoumou Land Tenure Center, University of Wisconsin–Madison with Peter C. Bloch Land Tenure Center, University of Wisconsin–Madison Under Subcontract to Development Alternatives, Inc. Financed by U.S. Agency for International Development, BASIS IQC LAG-I-00-98-0026-0 March 2003 Niger i Brief Contents Page 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Purpose of the country brief 1 1.2 Contents of the document 1 2. PROFILE OF NIGER AND ITS AGRICULTURE SECTOR AND AGRARIAN STRUCTURE 2 2.1 General background of the country 2 2.2 General background of the economy and agriculture 2 2.3 Land tenure background 3 2.4 Land conflicts and resolution mechanisms 3 3. EVIDENCE OF LAND MARKETS IN NIGER 5 4. INTERVENTIONS ON PROPERTY RIGHTS AND LAND MARKETS 7 4.1 The colonial regime 7 4.2 The Hamani Diori regime 7 4.3 The Kountché regime 8 4.4 The Rural Code 9 4.5 Problems facing the Rural Code 10 4.6 The Land Commissions 10 5. ASSESSMENT OF INTERVENTIONS ON PROPERTY RIGHTS AND LAND MARKET DEVELOPMENT 11 6. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 13 BIBLIOGRAPHY 15 APPENDIX I. SELECTED INDICATORS 25 Niger ii Brief NIGER COUNTRY BRIEF: PROPERTY RIGHTS AND LAND MARKETS Yazon Gnoumou with Peter C. Bloch 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 PURPOSE OF THE COUNTRY BRIEF The purpose of the country brief is to determine to which extent USAID’s programs to improve land markets and property rights have contributed to secure tenure and lower transactions costs in developing countries and countries in transition, thereby helping to achieve economic growth and sustainable development. -

Rapport AIC CRA Zinder

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER CHAMBRE REGIONALE D’AGRICULTURE DE ZINDER Etablissement public à caractère professionnel créé par la Loi 2000 15/ du 21 Août 2000 / Tél : (227) 20 512 343 - Email : [email protected] RAPPORT ANNUEL DES ACTIVITES DE LA CRA DE ZINDER DANS LE CADRE DU PARTENARIAT AVEC LE PASEC Rédigé par : MANA KOUDOUSSOU Ibrahim, chargé de mission AIC, CRA-Zinder. I. Introduction Ce rapport présente les activités menées par la CRA de Zinder du mois de mars au mois de décembre 2018 dans le cadre de son partenariat avec le Projet d’Appui à l’Agriculture sensible aux risques Climatiques (PASEC). La CRA est engagée dans les activités du PASEC à travers la convention signée par le Réseau National des Chambres d’Agriculture du Niger (RECA) pour la diffusion de l’information aux producteurs sur le climat et les techniques d’Agriculture Intelligente face au Climat (AIC). Il est composé des points suivants : • Dispositif mis en place • Situation des semences améliorées • Diffusion des émissions radios • Conseils aux producteurs sur les traitements phytosanitaires • Enrôlement des producteurs • Situation du Centre d’appels sur le financement • Participation au CRAP / Ateliers / missions • Autres activités (production du bourgou, inventaire motopompes, publications Facebook, notes rédigées). 2. Dispositif mis en place En mars 2018, la CRA de Zinder a recruté un chargé de mission AIC suite à un processus de recrutement transparent en plusieurs étapes : Elaboration des TDR partagés avec l’ANPE et diffusés sur le site du RECA ; Mise en place d’un comité de sélection comprenant : le Président de la CRA, le SP, la comptable, l’Assistante Technique et le Trésorier ; Présélection sur la base des dossiers : 30 dossiers de candidature enregistrés sur lesquels 8 ont été retenus. -

Niger Food Security Update, May/June 2008

NIGER Food Security Update May/June 2008 • The 2008/2009 growing season began with localized Figure 1. Current food security conditions (May/June rainfall, allowing farmers in some departments to start 2008) sowing crops. These regions have reported varying amounts of rainfall since the first dekad of April, with some rainfall gauging stations recording more than 100 mm of precipitation. Cumulative rainfall totals since this year’s start‐of‐season are below‐average in several locations throughout the country’s farm belt and agro‐pastoral zone although forecasts for the remainder of the season are good. • The growing season has begun on a troubling note for some poor, food‐deficit households. Most residents of the Tillabery region in Loga, Doutchi, Konni, Mirriah, Gouré and Mainé Soroa departments, having already depleted their household reserves, are now facing seed and food access problems, in addition to high prices. Source: FEWS NET Niger • In general, pasture availability in pastoral areas is adequate due to last year’s good pasture production. However, water availability for livestock may be limited, which could delay migration to the north, where rainfall rates are still low. This could trigger disputes between farmers and herders. • Therapeutic feeding centers are reporting a high incidence of malnutrition in general, and of severe malnutrition in particular. Admissions for May 2008 are up as much as 100 percent in some departments since April. Overall, a total of 17,863 new cases were reported in May, up from the 9,921 cases reported in April, an 80 percent increase. This surge in feeding center admissions is a reflection of food shortages and of typical seasonal deteriorations in health status. -

Niger Food Security Outlook, January

NIGER Food Security Outlook January - September 2008 • The food situation is deteriorating in northern Figure 1. Current food security assessment, January departments affected by armed conflict. Food security through March 2008 conditions are poor across Ouallam, Téra, Dakoro, Keita, Tahoua, Abalak, Mayahi, Tanout, Gouré, Dogon Doutchi, Loga, Nguigmi and Mainé Soroa departments due to dwindling reserves and an erosion in purchasing power. According to the findings by the joint survey of vulnerability to food insecurity conducted in November‐ December of 2007, 1,441,967 persons are classified as severely food‐insecure (12 percent of the country’s population), up from a figure of 1,100,000 for the same period of 2006. The food situation in Tillabery, Say, Filingué and Konni departments is improving and the state of nutrition is stable in the southern part of the country (Figure 1). • In the most likely scenario for the period from April Source: FEWS NET Niger through June of this year, off‐season crop availability will decline and households will begin to deplete their grain reserves, particularly in Doutchi, Loga, Ouallam and Téra departments and in large portions of the agropastoral area of Tahoua, Maradi, Zinder and Diffa departments. Crops will be available on local markets, but there will be a small seasonal upswing in prices. The food situation in the third quarter of the year, from July through September, should be normal for that time of year, with an average start‐of‐ season for 2008/09 crops in June and farmers and traders unloading their inventories and selling their grain crops. -

Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger

Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger Analysis Coordination March 2019 Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger 2019 About FEWS NET Created in response to the 1984 famines in East and West Africa, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) provides early warning and integrated, forward-looking analysis of the many factors that contribute to food insecurity. FEWS NET aims to inform decision makers and contribute to their emergency response planning; support partners in conducting early warning analysis and forecasting; and provide technical assistance to partner-led initiatives. To learn more about the FEWS NET project, please visit www.fews.net. Acknowledgements This publication was prepared under the United States Agency for International Development Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) Indefinite Quantity Contract, AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Recommended Citation FEWS NET. 2019. Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger. Washington, DC: FEWS NET. Famine Early Warning Systems Network ii Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger 2019 Table of Contents Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Background ............................................................................................................................................................................. -

Niger Staple Food and Livestock Market Fundamentals September 2017

NIGER STAPLE FOOD AND LIVESTOCK MARKET FUNDAMENTALS SEPTEMBER 2017 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. for the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), contract number AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. FEWS NET NIGER Staple Food and Livestock Market Fundamentals 2017 About FEWS NET Created in response to the 1984 famines in East and West Africa, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) provides early warning and integrated, forward-looking analysis of the many factors that contribute to food insecurity. FEWS NET aims to inform decision makers and contribute to their emergency response planning; support partners in conducting early warning analysis and forecasting; and provide technical assistance to partner-led initiatives. To learn more about the FEWS NET project, please visit www.fews.net. Disclaimer This publication was prepared under the United States Agency for International Development Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) Indefinite Quantity Contract, AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. Acknowledgements FEWS NET gratefully acknowledges the network of partners in Niger who contributed their time, analysis, and data to make this report possible. Cover photos @ FEWS NET and Flickr Creative Commons. Famine Early Warning Systems Network ii FEWS NET NIGER Staple Food and Livestock Market Fundamentals 2017 Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................................................... -

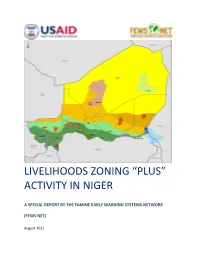

Livelihoods Zoning “Plus” Activity in Niger

LIVELIHOODS ZONING “PLUS” ACTIVITY IN NIGER A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) August 2011 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 4 National Livelihoods Zones Map ................................................................................................................... 6 Livelihoods Highlights ................................................................................................................................... 7 National Seasonal Calendar .......................................................................................................................... 9 Rural Livelihood Zones Descriptions ........................................................................................................... 11 Zone 1: Northeast Oases: Dates, Salt and Trade ................................................................................... 11 Zone 2: Aïr Massif Irrigated Gardening ................................................................................................ 14 Zone 3 : Transhumant and Nomad Pastoralism .................................................................................... 17 Zone 4: Agropastoral Belt ..................................................................................................................... -

Les Ressources Forestières Naturelles Et Les Plantations Forestières Au Niger

COMMISSION EUROPEENNE DIRECTION-GENERALE VIII DEVELOPPEMENT Collecte et analyse de données pour l’aménagement durable des forêts - joindre les efforts nationaux et internationaux Programme de partenariat CE-FAO (1998-2002) Ligne budgétaire forêt tropicale B7-6201/97-15/VIII/FOR PROJET GCP/INT/679/EC Les ressources forestières naturelles et les plantations forestières au Niger M. Laoualy Ada et Dr Ali Mahamane Août 1999 Ce rapport constitue un des résultats du Programme de partenariat CE-FAO (1998-2002) - GCP/INT/679/EC Collecte et analyse de données pour l’aménagement durable des forêts - joindre les efforts nationaux et internationaux. Les points de vue exprimés sont ceux des auteurs et ne peuvent être attribués ni à la CE, ni à la FAO. Le document est présenté dans une édition simple, pour un unique souci de style et de clarté. Table des matières : Liste des tableaux ..................................................................................................................... 4 Sigles et abréviations................................................................................................................ 6 Remerciements ......................................................................................................................... 7 Résumé ...................................................................................................................................... 7 Introduction ............................................................................................................................. -

Niger Staple Food and Livestock Market Fundamentals. September 2017

NIGER STAPLE FOOD AND LIVESTOCK MARKET FUNDAMENTALS SEPTEMBER 2017 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. for the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), contract number AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. FEWS NET NIGER Staple Food and Livestock Market Fundamentals 2017 About FEWS NET Created in response to the 1984 famines in East and West Africa, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) provides early warning and integrated, forward-looking analysis of the many factors that contribute to food insecurity. FEWS NET aims to inform decision makers and contribute to their emergency response planning; support partners in conducting early warning analysis and forecasting; and provide technical assistance to partner-led initiatives. To learn more about the FEWS NET project, please visit www.fews.net. Disclaimer This publication was prepared under the United States Agency for International Development Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) Indefinite Quantity Contract, AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. Acknowledgements FEWS NET gratefully acknowledges the network of partners in Niger who contributed their time, analysis, and data to make this report possible. Cover photos @ FEWS NET and Flickr Creative Commons. Famine Early Warning Systems Network ii FEWS NET NIGER Staple Food and Livestock Market Fundamentals 2017 Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................................................... -

Zinder: Carte Référentielle

Zinder: Carte référentielle Légende Tiguidan Tagait Chef lieu de région Chef lieu de département Localité AGADEZ Frontière internationale Frontière régionale Frontière départementale Frontière communale Agadez Route bitumée Route en latérite cour d'eau Région de Zinder Tesker Mayatta 0 50 100 kms Egade Farak Intabanout Tesker Takoukou Daoura Njeptoji Belbegi Gourbobo Diffa Tanout Kelle Ollelewa Chanyeta Batte Magaje Kekeni TANOUT Kokaram Bouzouzoum Dourwanga µ Gandou Maidiga Oubandawaki Chirwa Gouagourzo Gagawa Creation Date: 20 février 2015 Eldaweye Sabon Kafi Adjeri Projection/Datum: Coordonées Géographiques/WGS84 Gangara Tarka Boultoum Web Resources:http://ochaonline.un.org/niger Nominal Scale at A1 paper size: 1: 1 000 000 Yogoum Danbarko Gargada Guirdiguiski 2Gogo Guidan Ango Daoutcha Guezawa Map data source(s): Danmarke OCHA Niger Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this Gazamni Gueza map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the Falenco Kelle part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal Mai Sap Sap Bakin Birji status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or Baboul Damagaran Takaya Kazoe concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Kringuim Rahin Zomo Kanya Wame Damagaram Takaya Nyelwa Bourbouroua Krilla Raffa Magaje Alberkaram Moa Maikombarwa Biri Bouzouri Gogo Lassouri Chagna Goure Mazoza GOURE Annari Mazamni Takeita Kassama Maguirami Zounkouda Chagna Gabana Kafa Alkali Dan Gaya Chiya Ta Habou Karamba Babban Fague -

Challenges of Estimating the Annual Caseload of Severe Acute Malnutrition: the Case of Niger

RESEARCH ARTICLE Challenges of Estimating the Annual Caseload of Severe Acute Malnutrition: The Case of Niger Hedwig Deconinck1☯*, Anaïs Pesonen2☯, Mahaman Hallarou3‡, Jean- Christophe Gérard4‡, André Briend5,6☯, Philippe Donnen3‡, Jean Macq1‡ 1 Institut de recherche santé et société, Université catholique de Louvain, Brussels, Belgium, 2 École de médecine, Université catholique de Louvain, Brussels, Belgium, 3 École de santé publique, Université libre de Bruxelles, Brussels, Belgium, 4 Save the Children, Niamey, Niger, 5 Tampere Centre for Child Health Research, University of Tampere and Tampere University Hospital, Tampere, Finland, 6 Department of Nutrition, Exercise and Sports, Faculty of Science, University of Copenhagen, Frederiksberg, Denmark a11111 ☯ These authors contributed equally to this work. ‡ These authors also contributed equally to this work. * [email protected] Abstract OPEN ACCESS Introduction Citation: Deconinck H, Pesonen A, Hallarou M, Gérard J-C, Briend A, Donnen P, et al. (2016) Reliable prospective estimates of annual severe acute malnutrition (SAM) caseloads for Challenges of Estimating the Annual Caseload of treatment are needed for policy decisions and planning of quality services in the context of Severe Acute Malnutrition: The Case of Niger. PLoS competing public health priorities and limited resources. This paper compares the reliability ONE 11(9): e0162534. doi:10.1371/journal. of SAM caseloads of children 6–59 months of age in Niger estimated from prevalence at the pone.0162534 start of the year and counted from incidence at the end of the year. Editor: Abdisalan Mohamed Noor, Kenya Medical Research Institute - Wellcome Trust Research Programme, KENYA Methods Received: December 8, 2015 Secondary data from two health districts for 2012 and the country overall for 2013 were Accepted: August 24, 2016 used to calculate annual caseload of SAM.