Force Reductions, 1992–1995 167

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fiscal Year 2021 Efmb Locations

Host Unit/Site Dates Test Board Chairperson EFMB Slot POC/OIC/NCOIC FISCAL YEAR 2021 EFMB LOCATIONS In-Processing: 2nd Stryker Brigade Combat 26 September 2020 2nd Fl., BLDG 11265, 23rd St. Team, 2nd Infantry Division Standardization Dates: JBLM, WA 98433 2nd Fl., BLDG 11265, 23rd St. 27 – 1 October 2020 JBLM, WA 98433 Test Site: Testing Dates: COMM: (253) 878-0449 Joint Base Lewis-McChord, 2 – 8 October 2020 DSN: (253) 447-2284 COMM: (502) 712-5819 WA Approx. 50 Candidates In-Processing: 13 October 2020 1st Medical Brigade Standardization Dates: 33026 Support Ave. 33026 Support Ave. 13 – 23 October 2020 Fort Hood, TX 76544 Fort Hood, TX 76544 Test Site: Testing Dates: Fort Hood, TX 24 – 30 October 2020 COMM (254) 288-4118 COMM (254) 288-4118 Approx. 100 Candidates In-Processing: 25 October 2020 101st Airborne Division Standardization Dates: 2700 Indiana Avenue 2700 Indiana Avenue 25 – 30 October 2020 Fort Campbell KY, 42223 Test Site: Fort Campbell KY, 42223 Testing Dates: Fort Campbell, KY 31 October – 6 November 2020 Comm: 270-798-5880 Comm: 270-412-4193 Approx. 300 Candidates In-Processing: 5 November 2020 44th Medical Brigade 4204 Longstreet Road 4204 Longstreet Road Standardization Dates: Bldg. A-1983 Bldg. A-1983 5 – 10 November 2020 Test Site: Fort Bragg, NC 28310 Fort Bragg, NC 28310 Testing Dates: Fort Bragg, NC 11 – 17 November 2020 Comm: 910-432-9548 Comm: 910-568-7688 Approx. 150 Candidates In-Processing: 4 December 2020 25th Infantry Division 130 Grimes Street, Unit 5 (Hamilton 130 Grimes Street, Unit 5 (Hamilton Standardization Dates: Trailers), Rm 17 Trailers), Rm 17 4 - 11 December 2020 Test Site: Schofield Barracks, HI 96857 Schofield Barracks, HI 96857 Testing Dates: Schofield Barracks, HI 12 - 18 December 2020 Comm: (808) 787-5429 Comm: (808) 787-5427 Approx. -

Army Medical Specialist Corps in Vietnam Colonel Ann M

Army Medical Specialist Corps in Vietnam Colonel Ann M. Ritchie Hartwick Background Medical Groups which were established and dissolved as medical needs dictated throughout Though American military advisers had been the war. On 1 March 1970, Army medical dual in French Indochina since World War II, staff functions were reduced with the and the American Advisory Group with 128 establishment of the U.S. Army Medical positions was assigned to Saigon in 1950, the Command, Vietnam (Provisional). Army Surgeon General did not establish a hospital in Vietnam until 1962 (the Eighth The 68th Medical Group, operational on 18 Field Hospital at Nha Trang) to support March 1966, was located in Long Binh and American personnel in country. Between 1964 supported the medical mission in the III and IV and 1969 the number of American military combat tactical zones (CTZs). The 55th personnel in Vietnam increased from 23,000 Medical Group, operational in June 1966, to 550,000 as American combat units were supported the medical mission in the northern deployed to replace advisory personnel in II CTZ and was located at Qui Nhon. The 43d support of military operations. Medical Group, operational in November 1965, supported the medical mission for Between 1964 and 1973 the Army Surgeon southern II CTZ and was located at Nha Trang. General deployed 23 additional hospitals And, in October 1967, the 67th Medical established as fixed medical installations with Group, located at Da Nang, assumed area support missions. These included surgical, medical support responsibility for ICTZ. evacuation, and field hospitals and a 3,000 bed convalescent center, supported by a centralized blood bank, medical logistical support Army Physical Therapists installations, six medical laboratories, and The first member of the Army Medical multiple air ambulance ("Dust Off") units. -

Cofs, USA MEDCOM

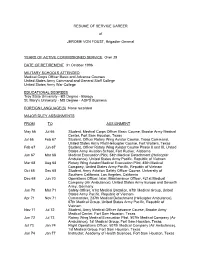

RESUME OF SERVICE CAREER of JEROME VON FOUST, Brigadier General YEARS OF ACTIVE COMMISSIONED SERVICE Over 29 DATE OF RETIREMENT 31 October 1996 MILITARY SCHOOLS ATTENDED Medical Corps Officer Basic and Advance Courses United States Army Command and General Staff College United States Army War College EDUCATIONAL DEGREES Troy State University - BS Degree - Biology St. Mary's University - MS Degree - ADPS Business FOREIGN LANGUAGE(S) None recorded MAJOR DUTY ASSIGNMENTS FROM TO ASSIGNMENT May 66 Jul 66 Student, Medical Corps Officer Basic Course, Brooke Army Medical Center, Fort Sam Houston, Texas Jul 66 Feb 67 Student, Officer Rotary Wing Aviator Course, Troop Command, United States Army Pilot/Helicopter Course, Fort Wolters, Texas Feb 67 Jun 67 Student, Officer Rotary Wing Aviator Course Phase II and III, United States Army Aviation School, Fort Rucker, Alabama Jun 67 Mar 68 Medical Evacuation Pilot, 54th Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance), United States Army Pacific, Republic of Vietnam Mar 68 Aug 68 Rotary Wing Aviator/Medical Evacuation Pilot, 45th Medical Company, United States Army Pacific, Republic of Vietnam Oct 68 Dec 68 Student, Army Aviation Safety Officer Course, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California Dec 68 Jun 70 Operations Officer, later, Maintenance Officer, 421st Medical Company (Air Ambulance), United States Army Europe and Seventh Army, Germany Jun 70 Mar 71 Safety Officer, 61st Medical Battalion, 67th Medical Group, United States Army Pacific, Republic of Vietnam Apr 71 Nov 71 Commander, 237th -

44TH MEDICAL BRIGADE NEWS Welcome to the Brigade

44TH MEDICAL BRIGADE NEWS Welcome to the Brigade Commander: In a ceremony on 29.- ay, Colonel Frederick W. Timmerman, formerly Command Surgeon, Headquarters, STRIKE Command, assumed command of the 44th Medical Brigade. Major General Charles W. Eifler, who officiated at the ceremony, awarded the Legion of Merit to the departing commander, Colonel Ray L. Miller. Colonel Miller was also the recipient of the Technical Service Honor Medal, First Class, presented by Colonel Hoan, Chief Surgeon, Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces. Other Coniand Chaes: Numerous command changes have recently taken place within the Brigade. LTC Henry Cosand is now acting CO of the 55th Medical Group and LTC Phillip H. Wvelch is commanding both 71st Evac and the 18th Surg following the departure of Mark T. Cenac. LTC Armin G. Dycaico has replaced LTC Elbert B. Fountain as comnander of the 70th Medical Battalion, MAJ John E. Rafferty is the new commander of the 7th Surg and LTC Kenneth R. Dirks has taken over the 406th Mobile Laboratory. COL Hinton J. Baker is the new CO of the 9th Med Lab and LTC Norman J. Glucksman is now in command of the 4th Med Det (Vet). Command of the 32nd Med Depot was assumed by LTC Richard S. Rand following the departure of COL Willianm W. Southard. Other Newcomers: The newly assigned Group Exec Officers include, LTC Roy L. Bates, 55th Group; LTC Robert M. Gerber, 68th Group; and LTC Reinhardt H. Kaddatz at the 43rd Group. Also new to the 43rd Group is LTC Owen W. Austin, who is the S-4. -

Matls License Package for Amend 60 to License 08-01738-02 for Dept Of

'.ORM 374 U.S. NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMISSION PAGE • OF 4 PAGES MATERIALS LICENSE Amendment No. 60 Pursuant to the Atomic Energy Act of 1954, as amended, the Energy Reorganization Act of 1974 (Public Law 93-438), and Title 10, Code of Federal Regulations, Chapter 1. Parts 30. 31, 32, 33. 34. 35. 39, 40 and 70. and in reliance on statements and representations heretofore made by the licensee, a license is hereby issued authorizing the licensee to receive, acquire, possess. and transfer byproduct, source, and special nuclear material designated below- to use such material for the purpose(s) and at the place(s) designated below; to deliver or transfer such material to persons authorized to receive it in accordance with the regulations of the applicable Part(s). This license shall be deemed to contain the conditions specified in Section 183 of the Atomic Energy Act of 1954. as amended, and is subject to all applicable rules, regulations and orders of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission now or hereafter in effect and to any conditions specified below. I- Licensee In accordance with letter dated July 11, 1991, . Department of the Army 3. License number 08-01738-02 is amended in Walter Reed Army Medical Center (WRAMC) its entirety to read as follows: 2. Washington, D.C. 20307-5001 4. Expiration date April 30, 1993 5. Docket or Reference No 030-01317 6. Byproduct. source, and/or 7. Chemical and/or physical 8. Maximum amount that licensee special nuclear material form may possess at any one time under this license A. Any byproduct material A. -

Badge. He Is Married to the Former Lori Johnson of Washington, D.C

Major General Michael J. Talley currently serves as the Deputy Commanding General for Operations, U.S. Army Medical Command. Major General Talley volunteered for military service in 1983, serving with the 1st Infantry Division and 197th Separate Infantry Brigade. He achieved the rank of Sergeant and was honorably discharged in 1989. He earned a Bachelor of Science degree with honors from the University of Texas at El Paso and commissioned as a Distinguished Military Graduate in 1991. Major General Talley has led in several previous command and key staff assignments, to include: Troop Commander, 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment; Logistics Officer, 7th Special Forces Group (Airborne); Observer/Controller (Project Warrior), Mechanized Infantry Task Force, National Training Center; G3 War Plans Officer, XVIII Airborne Corps; Director/Instructor, Combined Logistics Captains Career Course; Senior Task Force O/C, Joint Readiness Training Center; Commander, Defense Distribution Depot Tobyhanna, Pennsylvania; Commander, 6th Medical Logistics Management Center; Assistant Deputy Chief of Staff G-3/5/7, OTSG & USAMEDCOM; Commander, 44th Medical Brigade & Task Force MED, CJTF-CS; Army Forces Command Surgeon; Deputy Commanding General, Regional Health Command Atlantic; and most recently, Commanding General, U.S. Army Medical Research and Development Command & Fort Detrick. He served OIF combat tours as the Executive Officer of 261st Medical Battalion (ABN) and S3, 507th Corps Support Group (ABN), in addition to a deployment to Saudi Arabia as the Assistant Program Manager for Health Affairs, Office of the Program Manager, Saudi Arabian National Guard (OPM-SANG) Modernization Program. Major General Talley’s professional education includes the Combined Logistics Officer Advanced Course, Command and General Staff College & School of Advanced Military Studies, and the Army War College. -

105–275 Military Construction Appropriations for Fiscal Year 1998

S. HRG. 105±275 MILITARY CONSTRUCTION APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 1998 HEARINGS BEFORE A SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON H.R. 2016 AN ACT MAKING APPROPRIATIONS FOR MILITARY CONSTRUCTION FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDING SEP- TEMBER 30, 1998, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES Printed for the use of the Committee on Appropriations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 39±863 cc WASHINGTON : 1998 For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, Washington, DC 20402 COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS TED STEVENS, Alaska, Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico ERNEST F. HOLLINGS, South Carolina CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont SLADE GORTON, Washington DALE BUMPERS, Arkansas MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky FRANK R. LAUTENBERG, New Jersey CONRAD BURNS, Montana TOM HARKIN, Iowa RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire HARRY REID, Nevada ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah HERB KOHL, Wisconsin BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado PATTY MURRAY, Washington LARRY CRAIG, Idaho BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota LAUCH FAIRCLOTH, North Carolina BARBARA BOXER, California KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas STEVEN J. CORTESE, Staff Director LISA SUTHERLAND, Deputy Staff Director JAMES H. ENGLISH, Minority Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON MILITARY CONSTRUCTION CONRAD BURNS, Montana Chairman KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas PATTY MURRAY, Washington LAUCH FAIRCLOTH, North Carolina HARRY REID, Nevada LARRY CRAIG, Idaho DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii TED STEVENS, Alaska (ex officio) ROBERT C. -

Volume 1, 2008

Kerri Childress, Editor VISN 21 3801 Miranda Avenue Palo Alto, CA 94304-1290 www.visn21.med.va.gov Where to find us! VA MEDICAL CENTER VA MARE ISLAND OPC VA SAN JOSE OPC SAN FRANCISCO 201 Walnut Avenue 80 Great Oaks Boulevard 4150 Clement Street Mare Island, CA 94592 San Jose, CA 95119 San Francisco, CA 94121-1598 (707) 562-8200 (408) 363-3011 (415) 221-4810 OAKLAND MENTAL VA SONORA OPC DOWNTOWN S.F. VA OPC HEALTH AND SUBSTANCE 19747 Greenley Road 401 3rd Street abuce PROGRAM Sonora, CA 95370 San Francisco, Calif., 94107 Oakland Army Base (209) 588-2600 (415) 551-7300 2505 West 14th Street VA CENTRAL VA EUREKA OPC Oakland, CA 94607 CALIFORNIA HEALTH (510) 587-3400 714 F Street CARE SYSTEM Eureka, CA 95501 VA OAKLAND OPC 2615 E. Clinton Avenue (707) 442-5335 2221 Martin Luther King Jr. Way Fresno, CA 93703-2286 VA SAN BRUNO OPC Oakland, CA 94612 (559) 225-6100 (510) 267-7800 1001 Sneath Lane VA SOUTH VALLEY OPC VA MAUI OPC San Bruno, Calif., 94066 VA FAIRFIELD OPC 1050 North Cherry Street 203 Ho’ohana Street, Suite 303 (650) 615-6000 103 Bodin Circle, Bldg. 778 Tulare, CA 93274 Kahului, HI 96732 VA SANTA ROSA OPC Travis AFB, CA 94535 (559) 684-8703 (808) 871-2454 (707) 437-1800 3315 Chanate Road VA CASTLE OPC VA HILO OPC Santa Rosa, CA 95404 VA PALO ALTO 3605 Hospital Road, Suite D 1285 Waianuenue Ave., Suite 211 (707) 570-3855 HEALTH CARE SYSTEM Atwater, CA 95301-5140 Hilo, HI 96720 VA UKIAH OPC 3801 Miranda Avenue (209) 381-0105 (808) 935-3781 630 Kings Court Palo Alto, CA 94304-1290 VA SIERRA NEVADA VA KONA CBOC Ukiah, CA 95482 (650) -

XVIII Airborne and JTF South

OPERATION JUST CAUSE: XVIII Airborne Corps and Joint Task Force South Page 1 of 6 History Office XVIII Airborne Corps and Joint Task Force South OPERATION JUST CAUSE UNITED STATES SOUTHERN COMMAND (USSOUTHCOM) JOINT TASK FORCE SOUTH (XVIII AIRBORNE CORPS) NAVAL FORCES, PANAMA (NAVFOR) AIR FORCES, PANAMA (AFFOR) MARINE FORCES, PANAMA (MARFOR) ARMY FORCES, PANAMA (ARFOR) JOINT SPECIAL OPERATIONS TASK FORCE (JSOTF) AFFOR • 830th Air Division • 1st Special Operations Wing (AC-130) • 24th Composite Air Wing ◦ CORONET COVE (A-7D) ◾ Detachment, 114th Tactical Fighter Group [SD ANG] ◦ 24th Tactical Air Support Squadron (OA-37) ◦ Tactical Air Control Party ◦ 24th Medical Group ◦ 1978th Communications Group ◦ 630th Air Control and Warning Squadron ◦ OL-1 Air Rescue and Recovery Service ◦ 6933d Electronic Security Squadron • 61st Military Airlift Group (COMALF) https://history.army.mil/documents/panama/taskorg.htm 4/23/2019 OPERATION JUST CAUSE: XVIII Airborne Corps and Joint Task Force South Page 2 of 6 ◦ VOLANT OAK (C-130) ◦ 310th Military Airlift Squadron ◦ 6th Aerial Port Squadron • 430th Reconnaissance Technical Group (FURTIVE BEAR) • 4400th Air Postal Squadron NAVFOR • Naval Surface Warfare Unit 8 ◦ Special Boat Unit 26 ◦ Task Force WHITE • Naval Security Group (Galeta Island) • NAVSCIATTS • Mine Division 127 TASK FORCE SEMPER FI (MARFOR) • 6th Marine Expeditionary Battalion ◦ Company K, 3d Battalion, 6th Marines [to 5 Jan 90] ◦ Company I, 3d Battalion, 6th Marines [from 5 Jan 90] ◦ Company D, 2d Light Armored Infantry Battalion (-) [USMC] • Marine Security Element (Galeta Island) [USMC] • 1st Platoon, Fleet Anti-Terrorism Security Team [USMC] • 534th Military Police Company [Panama] • 536th Engineer Battalion [Panama] ◦ 6th Engineer Detachment ◦ 7th Engineer Detachment ◦ 285th Engineer Detachment • Battery D, 320th Field Artillery [Panama] • 2d Battalion, 27th Infantry (-) [D+] [Ft. -

Operation Desert Storm Support This Conclusion

United States General Accounting Office Washhqton, D.C. 20548 National Security and International AfPairs Division B-249273.1 August l&l992 The Honorable Beverly Byron Chairman, Subcommittee on Military Personnel and Compensation Committee on Armed Services House of Representatives Dear Madam Chairman: This report responds to your request that we review the Army’s effectiveness in deploying medical units in support of Operation Desert Shield/Desert Storm. As we promised in testimony on this subject before your Subcommittee, this report is a more detailed discussion of the problems that the Army encountered in mobilizing, deploying, and supporting medical units in the theater of operations. It contains recommendations to the Secretary of the Army for improving the readiness and operational effectiveness of Army medical units. We are sending copies of this report to the Chairmen of the House and Senate Committees on Armed Services and on Appropriations, the House Committee on Government Operations, the Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs, the Secretary of Defense, and other interested parties. We will also make copies available to others upon request. This report was prepared under the direction of Richard Davis, Director, Army Issues, who may be reached on (202) 275-4 141. Other major contributors are listed in appendix III. Sincerely yours, Frank C. Conahan Assistant Comptroller General Executive Summa~ Because of the high number of U.S. casualties expected during Operation Purpose Desert Shield/Desert Storm, the U.S. Army deployed about 23,000 medical personnel and shipped millions of dollars of medical materiel to the Persian Gulf. The Chairman of the Subcommittee on Military Personnel and Compensation, House Armed Services Committee, asked GAO to assess the Army’s effectiveness in deploying medical units and providing medical services during this war. -

Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences Archives

Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences Board of Regents Quarterly Meeting August 2018 BOARD OF REGENTS, UNIFORMED SERVICES UNIVERSITY OF THE HEALTH SCIENCES 204th MEETING 8:00 A.M. August 14, 2018 Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USU) Everett Alvarez Jr. Board of Regents Room (D3001) Bethesda, MD MEETING AGENDA OPEN MEETING 8:00am: Call Meeting to Order Designated Federal Officer Mrs. Jennifer Nuetzi James 8:00 - 8:10am: Opening Comments ...................................................................................... Tab 7 Board of Regents (Board) Chair Dr. Ronald Blanck 8:10 - 8:15am: Matters of General Consent Approval of May 2018 Minutes ................................................................................... Tab 9 Declaration of Board Actions .................................................................................... Tab 10 Board Chair Dr. Ronald Blanck 8:15 - 8:30am: Board Actions Degree Granting, F. Edward Hébert School of Medicine .......................................... Tab 11 Dean, School of Medicine Dr. Arthur Kellermann Degree Granting, Postgraduate Dental College ......................................................... Tab 12 Executive Dean, Postgraduate Dental College Dr. Thomas Schneid Degree Granting, College of Allied Health Sciences ................................................ Tab 13 Dean, College of Allied Health Sciences Dr. Mitchell Seal Faculty Appointments and Promotions ...................................................................... Tab 14 -

Rear Admiral Charles W. Brown Navy Chief of Information

Rear Admiral Charles W. Brown Navy Chief of Information Rear Adm. Charles W. Brown was born and raised on Long Island, New York, and he is a 1994 graduate of the United States Naval Academy. Brown holds a master's in Mass Communication and Media Studies from San Diego State University, and he is the first flag officer and senior active duty public affairs officer accredited in public relations and military communication. During more than 20 years as a public affairs officer (PAO), Brown has served as the fleet PAO for both U.S. Pacific Fleet and U.S. Third Fleet, the special assistant (Public Affairs) to the Chief of Naval Operations, the force PAO for U.S. Naval Air Forces, and the aircraft carrier and battle group PAO for USS Constellation (CV 64) and Cruiser Destroyer Group One. Brown has also served as deputy PAO for U.S. Fifth Fleet/U.S. Naval Forces Central Command, deputy PAO for Naval Surface Forces, and fleet media officer at U.S. Fleet Forces Command. Brown has led communication campaigns that have earned a Silver Anvil Award and an Award of Excellence from the Public Relations Society of America, a Thomas Jefferson award from the Department of Defense, and numerous Rear Admiral Thompson Awards for Excellence in Navy Public Affairs. He has deployed in direct support of Operation Southern Watch and Enduring Freedom. U.S. ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS Brig. Gen. Kimberly M. Colloton Commander and Division Engineer Transatlantic Division Brig. Gen. Kimberly M. Colloton assumed duties as Commander and Division Engineer of the U.S.