Graham Thomas Clews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Semaphore Circular No 661 the Beating Heart of the RNA July 2016

The Semaphore Circular No 661 The Beating Heart of the RNA July 2016 The No 3 Area Ladies getting the Friday night raffle ready at Conference! This edition is the on-line version of the Semaphore Circular, unless you have registered with Central Office, it will only be available on the RNA website in the ‘Members Area’ under ‘downloads’ at www.royal-naval-association.co.uk and will be emailed to the branch contact, usually the Hon Sec. 1 Daily Orders 1. Conference 2016 report 2. Remembrance Parade 13 November 2016 3. Slops/Merchandise & Membership 4. Guess Where? 5. Donations 6. Pussers Black Tot Day 7. Birds and Bees Joke 8. SAIL 9. RN VC Series – Seaman Jack Cornwell 10. RNRMC Charity Banquet 11. Mini Cruise 12. Finance Corner 13. HMS Hampshire 14. Joke Time 15. HMS St Albans Deployment 16. Paintings for Pleasure not Profit 17. Book – Wren Jane Beacon 18. Aussie Humour 19. Book Reviews 20. For Sale – Officers Sword Longcast “D’ye hear there” (Branch news) Crossed the Bar – Celebrating a life well lived RNA Benefits Page Shortcast Swinging the Lamp Forms Glossary of terms NCM National Council Member NC National Council AMC Association Management Committee FAC Finance Administration Committee NCh National Chairman NVCh National Vice Chairman NP National President DNP Deputy National President GS General Secretary DGS Deputy General Secretary AGS Assistant General Secretary CONA Conference of Naval Associations IMC International Maritime Confederation NSM Naval Service Memorial Throughout indicates a new or substantially changed entry 2 Contacts Financial Controller 023 9272 3823 [email protected] FAX 023 9272 3371 Deputy General Secretary 023 9272 0782 [email protected] Assistant General Secretary (Membership & Slops) 023 9272 3747 [email protected] S&O Administrator 023 9272 0782 [email protected] General Secretary 023 9272 2983 [email protected] Admin 023 92 72 3747 [email protected] Find Semaphore Circular On-line ; http://www.royal-naval-association.co.uk/members/downloads or.. -

Reginald James Morry's Memoirs of WWII

THE MORRY FAMILY WEBSITE -- HTTP://WEB.NCF.CA/fr307/ World War II Memoirs of Reginald James Morry Including an eyewitness account of the sinking of the German battleship “Bismarck”. Reginald James Morry 10/6/2007 Edited by C. J. Morry Following long standing Newfoundland maritime tradition, when hostilities broke out at the beginning of WWII, Reginald James Morry chose to serve in the “Senior Service”, the Royal Navy. This is his personal account of those momentous years, including one of the most crucial naval battles of the war, the sinking of the German battleship “Bismarck”. © Reginald James Morry; Edmonton, Alberta, Canada; 2007 World War II Memoirs of Reginald James Morry (then Able Seaman R. Morry P/SSX 31753) Including an eyewitness account of the sinking of the German battleship “Bismarck”. Newfoundland’s Military Legacy Newfoundland participated in both World Wars. Even though the province is small, it produced a famous Regiment of Infantry that fought in Gallipolis and from there to France. They lost quite a few men in Turkey and were decimated twice in France, once in Beaumont Hamel and again at Arras and other areas on the Somme. Total casualties (fatal) were 1305, and at sea 179 lost their lives. Of those that returned, many died of wounds, stress, and worn out hearts. They were given the title “Royal” for their role in the defence of Masnieres (the Battle for Cambrai) by King George VI, the reigning Monarch of the time. World War II is practically dead history, especially since some anti-Royals disbanded the regiment in 2002, as it's territorial section, according to the present army regime in HQ Ottawa, did not measure up!! During WWII the British changed the regiment over to Artillery so they became known as The Royal Newfoundland Light Artillery to lessen the chances of heavy losses. -

January Cover.Indd

Accessories 1:35 Scale SALE V3000S Masks For ICM kit. EUXT198 $16.95 $11.99 SALE L3H163 Masks For ICM kit. EUXT200 $16.95 $11.99 SALE Kfz.2 Radio Car Masks For ICM kit. KV-1 and KV-2 - Vol. 5 - Tool Boxes Early German E-50 Flakpanzer Rheinmetall Geraet sWS with 20mm Flakvierling Detail Set EUXT201 $9.95 $7.99 AB35194 $17.99 $16.19 58 5.5cm Gun Barrels For Trumpter EU36195 $32.95 $29.66 AB35L100 $21.99 $19.79 SALE Merkava Mk.3D Masks For Meng kit. KV-1 and KV-2 - Vol. 4 - Tool Boxes Late Defender 110 Hardtop Detail Set HobbyBoss EUXT202 $14.95 $10.99 AB35195 $17.99 $16.19 Soviet 76.2mm M1936 (F22) Divisional Gun EU36200 $32.95 $29.66 SALE L 4500 Büssing NAG Window Mask KV-1 Vol. 6 - Lubricant Tanks Trumpeter KV-1 Barrel For Bronco kit. GMC Bofors 40mm Detail Set For HobbyBoss For ICM kit. AB35196 $14.99 $14.99 AB35L104 $9.99 EU36208 $29.95 $26.96 EUXT206 $10.95 $7.99 German Heavy Tank PzKpfw(r) KV-2 Vol-1 German Stu.Pz.IV Brumbar 15cm STuH 43 Gun Boxer MRAV Detail Set For HobbyBoss kit. Jagdpanzer 38(t) Hetzer Wheel mask For Basic Set For Trumpeter kit - TR00367. Barrel For Dragon kit. EU36215 $32.95 $29.66 AB35L110 $9.99 Academy kit. AB35212 $25.99 $23.39 Churchill Mk.VI Detail Set For AFV Club kit. EUXT208 $12.95 SALE German Super Heavy Tank E-100 Vol.1 Soviet 152.4mm ML-20S for SU-152 SP Gun EU36233 $26.95 $24.26 Simca 5 Staff Car Mask For Tamiya kit. -

The Heroic Destroyer and "Lucky" Ship O.R.P. "Blyskawica"

Transactions on the Built Environment vol 65, © 2003 WIT Press, www.witpress.com, ISSN 1743-3509 The heroic destroyer and "lucky" ship O.R.P. "Blyskawica" A. Komorowski & A. Wojcik Naval University of Gdynia, Poland Abstract The destroyer O.R.P. "Blyskawica" is a precious national relic, the only remaining ship that was built before World War I1 (WW2). On the 5oth Anniversary of its service under the Polish flag, it was honoured with the highest military decoration - the Gold Cross of the Virtuti Militari Medal. It has been the only such case in the whole history of the Polish Navy. Its our national hero, war-veteran and very "lucky" warship. "Blyskawica" took part in almost every important operation in Europe throughout WW2. It sailed and covered the Baltic Sea, North Sea, all the area around Great Britain, the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea. During the war "Blyskawica" covered a distance of 148 thousand miles, guarded 83 convoys, carried out 108 operational patrols, participated in sinking two warships, damaged three submarines and certainly shot down four war-planes and quite probably three more. It was seriously damaged three times as a result of operational action. The crew casualties aggregated to a total of only 5 killed and 48 wounded petty officers and seamen, so it was a very "lucky" ship during WW2. In July 1947 the ship came back to Gdynia in Poland and started training activities. Having undergone rearmament and had a general overhaul, it became an anti-aircraft defence ship. In 1976 it replaced O.R.P. "Burza" as a Museum-Ship. -

A Historical Assessment of Amphibious Operations from 1941 to the Present

CRM D0006297.A2/ Final July 2002 Charting the Pathway to OMFTS: A Historical Assessment of Amphibious Operations From 1941 to the Present Carter A. Malkasian 4825 Mark Center Drive • Alexandria, Virginia 22311-1850 Approved for distribution: July 2002 c.. Expedit'onaryyystems & Support Team Integrated Systems and Operations Division This document represents the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the Department of the Navy. Approved for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. Specific authority: N0014-00-D-0700. For copies of this document call: CNA Document Control and Distribution Section at 703-824-2123. Copyright 0 2002 The CNA Corporation Contents Summary . 1 Introduction . 5 Methodology . 6 The U.S. Marine Corps’ new concept for forcible entry . 9 What is the purpose of amphibious warfare? . 15 Amphibious warfare and the strategic level of war . 15 Amphibious warfare and the operational level of war . 17 Historical changes in amphibious warfare . 19 Amphibious warfare in World War II . 19 The strategic environment . 19 Operational doctrine development and refinement . 21 World War II assault and area denial tactics. 26 Amphibious warfare during the Cold War . 28 Changes to the strategic context . 29 New operational approaches to amphibious warfare . 33 Cold war assault and area denial tactics . 35 Amphibious warfare, 1983–2002 . 42 Changes in the strategic, operational, and tactical context of warfare. 42 Post-cold war amphibious tactics . 44 Conclusion . 46 Key factors in the success of OMFTS. 49 Operational pause . 49 The causes of operational pause . 49 i Overcoming enemy resistance and the supply buildup. -

1 Introduction

Notes 1 Introduction 1. Donald Macintyre, Narvik (London: Evans, 1959), p. 15. 2. See Olav Riste, The Neutral Ally: Norway’s Relations with Belligerent Powers in the First World War (London: Allen and Unwin, 1965). 3. Reflections of the C-in-C Navy on the Outbreak of War, 3 September 1939, The Fuehrer Conferences on Naval Affairs, 1939–45 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1990), pp. 37–38. 4. Report of the C-in-C Navy to the Fuehrer, 10 October 1939, in ibid. p. 47. 5. Report of the C-in-C Navy to the Fuehrer, 8 December 1939, Minutes of a Conference with Herr Hauglin and Herr Quisling on 11 December 1939 and Report of the C-in-C Navy, 12 December 1939 in ibid. pp. 63–67. 6. MGFA, Nichols Bohemia, n 172/14, H. W. Schmidt to Admiral Bohemia, 31 January 1955 cited by Francois Kersaudy, Norway, 1940 (London: Arrow, 1990), p. 42. 7. See Andrew Lambert, ‘Seapower 1939–40: Churchill and the Strategic Origins of the Battle of the Atlantic, Journal of Strategic Studies, vol. 17, no. 1 (1994), pp. 86–108. 8. For the importance of Swedish iron ore see Thomas Munch-Petersen, The Strategy of Phoney War (Stockholm: Militärhistoriska Förlaget, 1981). 9. Churchill, The Second World War, I, p. 463. 10. See Richard Wiggan, Hunt the Altmark (London: Hale, 1982). 11. TMI, Tome XV, Déposition de l’amiral Raeder, 17 May 1946 cited by Kersaudy, p. 44. 12. Kersaudy, p. 81. 13. Johannes Andenæs, Olav Riste and Magne Skodvin, Norway and the Second World War (Oslo: Aschehoug, 1966), p. -

The War Room Managed North Sea Trap 1907-1916

Michael H. Clemmesen 31‐12‐2012 The War Room Managed North Sea Trap 1907‐1916. The Substance, Roots and Fate of the Secret Fisher‐Wilson “War Plan”. Initial remarks In 1905, when the Royal Navy fully accepted the German High Seas Fleet as its chief opponent, it was already mastering and implementing reporting and control by wireless telegraphy. The Admiralty under its new First Sea Lord, Admiral John (‘Jacky’) Fisher, was determined to employ the new technology in support and control of operations, including those in the North Sea; now destined to become the main theatre of operations. It inspired him soon to believe that he could centralize operational control with himself in the Admiralty. The wireless telegraph communications and control system had been developed since 1899 by Captain, soon Rear‐Admiral Henry Jackson. Using the new means of communications and intelligence he would be able to orchestrate the destruction of the German High Seas Fleet. He already had the necessary basic intelligence from the planned cruiser supported destroyer patrols off the German bases, an operation based on the concept of the observational blockade developed by Captain George Alexander Ballard in the 1890s. Fisher also had the required The two officers who supplied the important basis for the plan. superiority in battleships to divide the force without the risk of one part being To the left: George Alexander Ballard, the Royal Navy’s main conceptual thinker in the two decades defeated by a larger fleet. before the First World War. He had developed the concept of the observational blockade since the 1890s. -

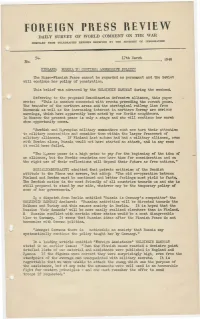

Foreign Press Review Daily Survey of World Comment on the War

FOREIGN PRESS REVIEW DAILY SURVEY OF WORLD COMMENT ON THE WAR OOMPILED FROM TELEGRAPHIO REPORTS RECEIVED BY THE MINISTRY OF INFORMATION ...........17th................. Uarch............. ........................... 1940 No. , FINLAND: RUSSIA TO CONTINlJ.G AGGRESSIVE POLICY? The Russo-Finnish Peace cannot be regarded as permanent and the Soviet will continue her policy of penetration. This belief was advanced by the HELSINGIN SANO:Wi.AT during the weekend. Referring to the proposed Scandinavian defensive alliance, this paper wrote: "This is somehow connected with events preoeding the re~ent peaee. The transfer of the northern areas and the strategical railway line from Murmansk as well as the increasing interest in northern Norway are serious warnings, vmich have apparently been noted by our Nordic neughbours. In Moscow the present peace is only a stage and she vvill continue her mareh vmen opportunity comes. "Swedish and. N0 rwegian military connna.nders must now turn their attent.i~n to military necessities and consider them within the larger framework of military alliances. If Finland. last autumn had had a military alliance, even with Sweden alone, Russia would not have started an attack, and in any case it would have failed. "The 1V~0 scov1 peace is a high price to pay for the beginning of the idea of an alliance, but the Nordic countries now· have time for consideration and on ---· the right use of their reflections vd.11 depend their future as free nations," SOSB.LIDhMOKR!'.\ATTI admitted that private cri tioism of the Swedish attitude to the Finns was severe, but ad.ded:, "The old co-operation between Finland and Sweden must be continued and bttter feelings must yield to facts. -

Saber and Scroll Journal Volume V Issue IV Fall 2016 Saber and Scroll Historical Society

Saber and Scroll Journal Volume V Issue IV Fall 2016 Saber and Scroll Historical Society 1 © Saber and Scroll Historical Society, 2018 Logo Design: Julian Maxwell Cover Design: Cincinnatus Leaves the Plow for the Roman Dictatorship, by Juan Antonio Ribera, c. 1806. Members of the Saber and Scroll Historical Society, the volunteer staff at the Saber and Scroll Journal publishes quarterly. saberandscroll.weebly.com 2 Editor-In-Chief Michael Majerczyk Content Editors Mike Gottert, Joe Cook, Kathleen Guler, Kyle Lockwood, Michael Majerczyk, Anne Midgley, Jack Morato, Chris Schloemer and Christopher Sheline Copy Editors Michael Majerczyk, Anne Midgley Proofreaders Aida Dias, Frank Hoeflinger, Anne Midgley, Michael Majerczyk, Jack Morato, John Persinger, Chris Schloemer, Susanne Watts Webmaster Jona Lunde Academic Advisors Emily Herff, Dr. Robert Smith, Jennifer Thompson 3 Contents Letter from the Editor 5 Fleet-in-Being: Tirpitz and the Battle for the Arctic Convoys 7 Tormod B. Engvig Outside the Sandbox: Camels in Antebellum America 25 Ryan Lancaster Aethelred and Cnut: Saxon England and the Vikings 37 Matthew Hudson Praecipitia in Ruinam: The Decline of the Small Roman Farmer and the Fall of the Roman Republic 53 Jack Morato The Washington Treaty and the Third Republic: French Naval 77 Development and Rivalry with Italy, 1922-1940 Tormod B. Engvig Book Reviews 93 4 Letter from the Editor The 2016 Fall issue came together quickly. The Journal Team put out a call for papers and indeed, Saber and Scroll members responded, evidencing solid membership engagement and dedication to historical research. This issue contains two articles from Tormod Engvig. In the first article, Tormod discusses the German Battleship Tirpitz and its effect on allied convoys during WWII. -

Hms Sheffield Commission 1975

'During the night the British destroyers appeared once more, coming in close to deliver their torpedoes again and again, but the Bismarck's gunnery was so effective that none of them was able to deliver a hit. But around 08.45 hours a strongly united attack opened, and the last fight of the Bismarck began. Two minutes later, Bismarck replied, and her third volley straddled the Rodney, but this accuracy could not be maintained because of the continual battle against the sea, and, attacked now from three sides, Bismarck's fire was soon to deteriorate. Shortly after the battle commenced a shell hit the combat mast and the fire control post in the foremast broke Gerhard Junack, Lt Cdr (Eng), away. At 09.02 hours, both forward heavy gun turrets were put out of action. Bismarck, writing in Purnell's ' A further hit wrecked the forward control post: the rear control post was History of the Second World War' wrecked soon afterwards... and that was the end of the fighting instruments. For some time the rear turrets fired singly, but by about 10.00 hours all the guns of the Bismarck were silent' SINK the Bismarck' 1 Desperately fighting the U-boat war and was on fire — but she continued to steam to the picture of the Duchess of Kent in a fearful lest the Scharnhorst and the south west. number of places. That picture was left Gneisenau might attempt to break out in its battered condition for the re- from Brest, the Royal Navy had cause for It was imperative that the BISMARCK be mainder of SHEFFIELD'S war service. -

World War II at Sea This Page Intentionally Left Blank World War II at Sea

World War II at Sea This page intentionally left blank World War II at Sea AN ENCYCLOPEDIA Volume I: A–K Dr. Spencer C. Tucker Editor Dr. Paul G. Pierpaoli Jr. Associate Editor Dr. Eric W. Osborne Assistant Editor Vincent P. O’Hara Assistant Editor Copyright 2012 by ABC-CLIO, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data World War II at sea : an encyclopedia / Spencer C. Tucker. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-59884-457-3 (hardcopy : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-59884-458-0 (ebook) 1. World War, 1939–1945—Naval operations— Encyclopedias. I. Tucker, Spencer, 1937– II. Title: World War Two at sea. D770.W66 2011 940.54'503—dc23 2011042142 ISBN: 978-1-59884-457-3 EISBN: 978-1-59884-458-0 15 14 13 12 11 1 2 3 4 5 This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. Visit www.abc-clio.com for details. ABC-CLIO, LLC 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper Manufactured in the United States of America To Malcolm “Kip” Muir Jr., scholar, gifted teacher, and friend. This page intentionally left blank Contents About the Editor ix Editorial Advisory Board xi List of Entries xiii Preface xxiii Overview xxv Entries A–Z 1 Chronology of Principal Events of World War II at Sea 823 Glossary of World War II Naval Terms 831 Bibliography 839 List of Editors and Contributors 865 Categorical Index 877 Index 889 vii This page intentionally left blank About the Editor Spencer C. -

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society The Old angbournianP Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society First published in the UK 2020 The Old Pangbournian Society Copyright © 2020 The moral right of the Old Pangbournian Society to be identified as the compiler of this work is asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, “Beloved by many. stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any Death hides but it does not divide.” * means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the Old Pangbournian Society in writing. All photographs are from personal collections or publicly-available free sources. Back Cover: © Julie Halford – Keeper of Roll of Honour Fleet Air Arm, RNAS Yeovilton ISBN 978-095-6877-031 Papers used in this book are natural, renewable and recyclable products sourced from well-managed forests. Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro, designed and produced *from a headstone dedication to R.E.F. Howard (30-33) by NP Design & Print Ltd, Wallingford, U.K. Foreword In a global and total war such as 1939-45, one in Both were extremely impressive leaders, soldiers which our national survival was at stake, sacrifice and human beings. became commonplace, almost routine. Today, notwithstanding Covid-19, the scale of losses For anyone associated with Pangbourne, this endured in the World Wars of the 20th century is continued appetite and affinity for service is no almost incomprehensible.