Modernist Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

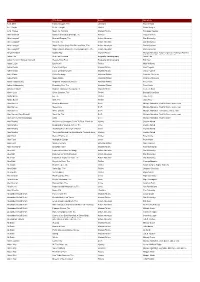

List of All the Audiobooks That Are Multiuse (Pdf 608Kb)

Authors Title Name Genre Narrators A. D. Miller Faithful Couple, The Literature Patrick Tolan A. L. Gaylin If I Die Tonight Thriller Sarah Borges A. M. Homes Music for Torching Modern Fiction Penelope Rawlins Abbi Waxman Garden of Small Beginnings, The Humour Imogen Comrie Abie Longstaff Emerald Dragon, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Firebird, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Blizzard Bear, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Young Apprentice, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abigail Tarttelin Golden Boy Modern Fiction Multiple Narrators, Toby Longworth, Penelope Rawlins, Antonia Beamish, Oliver J. Hembrough Adam Hills Best Foot Forward Biography Autobiography Adam Hills Adam Horovitz, Michael Diamond Beastie Boys Book Biography Autobiography Full Cast Adam LeBor District VIII Thriller Malk Williams Adèle Geras Cover Your Eyes Modern Fiction Alex Tregear Adèle Geras Love, Or Nearest Offer Modern Fiction Jenny Funnell Adele Parks If You Go Away Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adele Parks Spare Brides Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adrian Goldsworthy Brigantia: Vindolanda, Book 3 Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adrian Goldsworthy Encircling Sea, The Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adriana Trigiani Supreme Macaroni Company, The Modern Fiction Laurel Lefkow Aileen Izett Silent Stranger, The Thriller Bethan Dixon-Bate Alafair Burke Ex, The Thriller Jane Perry Alafair Burke Wife, The Thriller Jane Perry Alan Barnes Death in Blackpool Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes Nevermore Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes White Ghosts Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Tom Baker, and a. cast Alan Barnes, Gary Russell Next Life, The Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. -

Preacher's Magazine Volume 61 Number 04 Wesley Tracy (Editor) Olivet Nazarene University

Olivet Nazarene University Digital Commons @ Olivet Preacher's Magazine Church of the Nazarene 6-1-1986 Preacher's Magazine Volume 61 Number 04 Wesley Tracy (Editor) Olivet Nazarene University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/cotn_pm Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, International and Intercultural Communication Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, and the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Tracy, Wesley (Editor), "Preacher's Magazine Volume 61 Number 04" (1986). Preacher's Magazine. 597. https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/cotn_pm/597 This Journal Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Church of the Nazarene at Digital Commons @ Olivet. It has been accepted for inclusion in Preacher's Magazine by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Olivet. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JUNE, JULY, AUGUST, 1986 MAGAZINE BtNNER LIBKART OLIVET NAZARENE COLLEGJ KANKAKEE, ILLINOIS IICAL PREACHING....................... 6 JOHN WESLEY AND SCRIPTURE.................. .12 CONGREGATIONAL SINGING................ ..30 PARSONAGE OR HOUSING ALLOWANCE?.. ..3 2 A PUBLISHING EVENT.................................... ..38 TEACHING LIKE JESUS.................................. .4 4 Quitable Framing Wounded Hands by Charles R. Carey I beheld a horseman, riding. Perhaps the thunder Was the crashing of the hooves Of His fiery steed, And perhaps the lightning Was the flashing of His sword. He wheeled about And His sword was held high. His eyes were as burning coals, And His feet were polished brass. And perhaps His garment Was the finest white linen and Perhaps it was light. Hooves came crashing down And my vision cleared And my knees became water. -

Pianodisc Music Catalog.Pdf

Welcome Welcome to the latest edition of PianoDisc's Music Catalog. Inside you’ll find thousands of songs in every genre of music. Not only is PianoDisc the leading manufacturer of piano player sys- tems, but our collection of music software is unrivaled in the indus- try. The highlight of our library is the Artist Series, an outstanding collection of music performed by the some of the world's finest pianists. You’ll find recordings by Peter Nero, Floyd Cramer, Steve Allen and dozens of Grammy and Emmy winners, Billboard Top Ten artists and the winners of major international piano competi- tions. Since we're constantly adding new music to our library, the most up-to-date listing of available music is on our website, on the Emusic pages, at www.PianoDisc.com. There you can see each indi- vidual disc with complete song listings and artist biographies (when applicable) and also purchase discs online. You can also order by calling 800-566-DISC. For those who are new to PianoDisc, below is a brief explana- tion of the terms you will find in the catalog: PD/CD/OP: There are three PianoDisc software formats: PD represents the 3.5" floppy disk format; CD represents PianoDisc's specially-formatted CDs; OP represents data disks for the Opus system only. MusiConnect: A Windows software utility that allows Opus7 downloadable music to be burned to CD via iTunes. Acoustic: These are piano-only recordings. Live/Orchestrated: These CD recordings feature live accom- paniment by everything from vocals or a single instrument to a full-symphony orchestra. -

Doctor Who Assistants

COMPANIONS FIFTY YEARS OF DOCTOR WHO ASSISTANTS An unofficial non-fiction reference book based on the BBC television programme Doctor Who Andy Frankham-Allen CANDY JAR BOOKS . CARDIFF A Chaloner & Russell Company 2013 The right of Andy Frankham-Allen to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Copyright © Andy Frankham-Allen 2013 Additional material: Richard Kelly Editor: Shaun Russell Assistant Editors: Hayley Cox & Justin Chaloner Doctor Who is © British Broadcasting Corporation, 1963, 2013. Published by Candy Jar Books 113-116 Bute Street, Cardiff Bay, CF10 5EQ www.candyjarbooks.co.uk A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. Dedicated to the memory of... Jacqueline Hill Adrienne Hill Michael Craze Caroline John Elisabeth Sladen Mary Tamm and Nicholas Courtney Companions forever gone, but always remembered. ‘I only take the best.’ The Doctor (The Long Game) Foreword hen I was very young I fell in love with Doctor Who – it Wwas a series that ‘spoke’ to me unlike anything else I had ever seen. -

© 2014 Derek Yaniger, Derekart.Com Table of Contents

© 2014 Derek Yaniger, derekart.com Table of Contents Welcome to Dragon Con! .............................................3 National (NSDM).................................................35 Dealers Tables ..........................................................60 Convetion Policies .......................................................4 Paranormal Track (PN) .........................................36 Exhibitors Booths ......................................................62 Vital Information .........................................................4 Podcasting (POD) ................................................38 Comics Artists Alley ...................................................64 Courtesy Buses and MARTA Schedules ..........................5 Puppetry (PT) .....................................................91 Art Show: Participating Artists ....................................66 Hours of Operation ......................................................5 Reading Sessions (READ) .....................................92 Hyatt Atlanta Special Events ............................................................7 Robotics and Maker Track (ROBOT) .......................93 Hyatt Regency Hotel Map .....................................68 Hotel Floor Level Reference ..........................................7 Sci-fi Literature (SFL) ...........................................93 Hyatt: Ballroom Level ..........................................69 Fan Tracks Information and Room Locations ...................8 Science (SCI) ......................................................94 -

Alyssa Michaud Department of Music Research Schulich School Of

AFTER THE MUSIC BOX: A HISTORY OF AUTOMATION IN REAL-TIME MUSICAL PERFORMANCE Alyssa Michaud Department of Music Research Schulich School of Music McGill University, Montreal August 2019 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology © Alyssa Michaud 2019 i TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ iii Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... v Résumé .......................................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................ ix Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Music and Technology: An Overview ........................................................................................ 7 Research Methods and Chapter Breakdown ............................................................................. 20 Who are the Mechanics? ........................................................................................................... 20 Chapter 1: The Player Piano: From Domestic Machine to Expressive Instrument ..................... -

Gustav Mahler's Third Symphony

Gustav Mahler’s Third Symphony: Program, Reception, and Evocations of the Popular by Timothy David Freeze A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music Musicology) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Steven M. Whiting, Co-Chair Professor Albrecht Riethmüller, Freie Universität Berlin, Co-Chair Professor Roland J. Wiley Professor Michael D. Bonner Associate Professor Mark A. Clague © 2010 Timothy David Freeze All rights reserved To Grit ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The road leading to the completion of this dissertation was longer and more scenic than I ever intended it to be. It is a great pleasure to acknowledge here the many individuals and organizations that provided support and encouragement along the way. I am especially grateful to the co-chairs of my committee. Without the unflagging support of Steven M. Whiting, whose sage counsel on matters musical and practical guided me from start to finish, this project would not have been possible. I am equally indebted to Albrecht Riethmüller, whose insight and intellectual example were a beacon by whose light this dissertation took shape. I would also like to thank R. John Wiley, whose extensive and penetrating feedback improved the dissertation and my own thinking in countless ways, and Mark Clague and Michael Bonner, both of whom provided valuable comments on content and style. In Ann Arbor, I would like to acknowledge the support of the entire musicology faculty at the University of Michigan. Louise K. Stein gave helpful advice in the early stages of this project. In Berlin, I benefited from conversations with Federico Celestini, Sherri Jones, and Peter Moormann. -

Messiah: His Final Call to Israel

1 Messianic Series Volume Seven Isa. 1:18 לכו־נא ונוכחה יאמר יהוה “Come now and let us reason together, saith Jehovah” MESSIAH: HIS FINAL CALL TO ISRAEL BY DAVID L. COOPER., TH.M., PH.D., LITT.D. Founder and President, Biblical Research Society To The memory of FLORENCE LITA COOPER Faithful and beloved wife of the author And true friend of God’s Chosen People Israel is this volume dedicated. Copyrighted 1962 BY DAVID L. COOPER Library of Congress, Catalogue Card Number 62-12764 biblicalresearch.info 2 Preface The present volume, Messiah: His Final Call To Israel, is the seventh and last book of my Messianic Series, which consists of the following volumes: The God of Israel, which sets forth the scriptural teaching of God's existence, His character, and His nature—especially the triune nature of the Godhead; Messiah: His Nature and Person, which presents the scriptural teaching that one of the persons of the Godhead would assume human form and come to earth to execute the plan of redemption; Messiah: His Redemptive Career, which foretells the two comings of the one Messiah and the interval separating these two events, during which the rejected Messiah, having been executed, is seated at the right hand of God the Father in glory; Messiah: His First Coming Scheduled, which sets forth the system of Biblical chronology and which points to the time of His first coming; Messiah: His Historical Appearance, which presents the scriptural evidence that all the predictions in the Old Testament regarding Messiah's first coming have been fulfilled -

Australian Literature and Music, 1945 to Present

The Space and Time of Imagined Sound: Australian Literature and Music, 1945 to Present Joseph Cummins A thesis in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences 2015 Acknowledgements Since I started as an undergraduate, Elizabeth McMahon and John Napier have inspired and guided my intellectual pathway. I’ll always remember John playing Bartok and Ravel, and Liz lecturing on Whitman and Tsiolkas. Without their encouragement, knowledge, discussion, editing skills and advice this project would not have taken place. Thank you both. Ashley Barnwell. Thank you for all your encouragement, inspiration, support, and love. You are my partner in crime, always willing to discuss, deconstruct, and argue. Thanks for your help in the last six months of this project, for pushing my writing, and for reading through the final copy. Alister Spence, Phil Slater and Helen Groth have been great and generous mentors to me during my time at UNSW. Thank you for your encouragement and advice. A particular thank you to Al and Phil, from whom I learnt so much. Thanks to my family, my music family, ASAL, AAL, IASPM, CMSA, Maroubra, Sydney Roosters, and International Grammar School. For sparking my love of the literary and historical, and for her encouragement, example of open mindedness and discussion, and genuine interest in my work, this thesis is dedicated to Nan Colleen. Abstract This thesis examines the space and time of imagined sound in Australian post-World War Two literature and music. Using what I term a critical close listening methodology, I will discuss a range of novels, poems, songs, song suites, film clips and art music compositions that, through a return to various times in the past, offer a remapping of Australian space. -

Where Do Most Want to Live?

Weinhart’s walkabout EDITION West Linn resident tackles Pacic Crest trail — SEE LIFE, B10 GREATER PORTLAND PortlandTUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 9, 2014 • TWICE CHOSEN THE NATION’S BEST NONDAILY PAPERTribune • PORTLANDTRIBUNE.COM • PUBLISHED TUESDAY AND THURSDAY Urban Where do most want vote key to live? In the suburbs to GMO Metro study sees population shift, critics say numbers skewed campaign By JIM REDDEN single-family detached home the Portland Region was under- The Tribune with a yard. And more people taken by Metro, the elected prefer the suburbs instead regional government. The Opponents see a The traditional American of downtown and close-in results are the most in-depth and Dream is alive and well in the neighborhoods. complete ever gathered in the tough time in some Portland area. Those are among the results metropolitan area. And they fly Despite all the buzz about tiny of the most comprehensive study in the face of national surveys PAMPLIN MEDIA GROUP FILE PHOTO areas, but could win homes on wheels and apart- on housing preferences ever con- that claim most people prefer to More than three dozen new homes have been constructed in the ments with no designated park- ducted in Portland and sur- live in cities. Bronson Creek development on West Union Road in Washington County. By MATEUSZ PERKOWSKI ing, most Portland-area resi- rounding communities. The A new study says many people still desire the suburban lifestyle. Pamplin Media Group dents want to live in their own Residential Preference Study for See HOUSING / Page 6 The fate of Oregon’s geneti- cally modified organism la- beling initiative will hinge on whether heavy spending by “It is so deceiving where the creek goes into that water. -

Life-Of-Jesus-Harmonized.Pdf

Harmonized Gospels READER’S EDITION BIBLE BroadStreet Publishing® Group, LLC Savage, Minnesota, USA BroadStreetPublishing .com ThePassionTranslation.com The Life of Jesus: Harmonized Gospels, Reader’s Edition, The Passion Translation® Copyright © 2018 BroadStreet Publishing® Group, LLC 978- 1- 4245- 5666- 3 (faux) 978- 1- 4245- 5667- 0 (e- book) The Passion Translation®, Copyright © 2018 Passion & Fire Ministries, Inc. The Passion Translation® is a registered trademark of Passion & Fire Ministries, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, except as noted below, without permission in writing from the publisher. The text from The Life of Jesus may be quoted in any form (written, visual, electronic, or audio), up to and inclusive of 200 verses or less, without written permission from the publisher, provided that the verses quoted do not amount to a complete book of the Bible, nor do verses quoted account for 20 percent or more of the total text of the work in which they are quoted, and the verses are not being quoted in a commentary or other biblical reference work. When quoted, one of the following credit lines must appear on the copyright page of the work: Scripture quotations marked TPT are from The Passion Translation®, The Life of Jesus: Harmonized Gospels, Reader’s Edition. Copyright © 2018 by Passion & Fire Ministries, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved. ThePassionTranslation.com. All Scripture quotations are from The Passion Translation®, The Life of Jesus: Harmonized Gospels, Reader’s Edition. Copyright © 2018 by Passion & Fire Ministries, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved. ThePassionTranslation.com. -

Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright Adaptation and Twentieth-Century Opera Carolyn Claire Isabelle Burns A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of Sydney 2014 i Abstract Combining critical theory and dramaturgical analysis, this thesis considers twentieth-century English- language opera adaptations from a structural and cultural perspective, with particular focus on the increasing complexity of relationships between different types of literary text and the position of contemporary opera within national literary cultures.