Australian Literature and Music, 1945 to Present

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Meaning of Yaroomba II

Revisiting the place name meaning of Yaroomba The Gaiarbau, ‘bunya country’ and ‘thick vine scrub’ connections (by Kerry Jones, Arnold Jones, Sean Fleischfresser, Rodney Jones, Lore?a Algar, Helen Jones & Genevieve Jones) The Sunshine Coast region, fiHy years ago, may have had the greatest use of place names within Queensland derived from Aboriginal language words, according to researcher, E.G. Heap’s 1966 local history arQcle, ‘In the Wake of the Rasmen’. In the early days of colonisaon, local waterways were used to transport logs and Qmber, with the use of Aboriginal labour, therefore the term ‘rasmen’. Windolf (1986, p.2) notes that historically, the term ‘Coolum District’ included all the areas of Coolum Beach, Point Arkwright, Yaroomba, Mount Coolum, Marcoola, Mudjimba, Pacific Paradise and Peregian. In the 1960’s it was near impossible to take transport to and access or communicate with these areas, and made that much more difficult by wet or extreme weather. Around this Qme the Sunshine Coast Airport site (formerly the Maroochy Airport) having Mount Coolum as its backdrop, was sQll a Naonal Park (QPWS 1999, p. 3). Figure 1 - 1925 view of coastline including Mount Coolum, Yaroomba & Mudjimba Island north of the Maroochy Estuary In October 2014 the inaugural Yaroomba Celebrates fesQval, overlooking Yaroomba Beach, saw local Gubbi Gubbi (Kabi Kabi) TradiQonal Owner, Lyndon Davis, performing with the yi’di’ki (didgeridoo), give a very warm welcome. While talking about Yaroomba, Lyndon stated this area too was and is ‘bunya country’. Windolf (1986, p.8) writes about the first Qmber-ge?ers who came to the ‘Coolum District’ in the 1860’s. -

The Ithacan, 1990-10-04

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC The thI acan, 1990-91 The thI acan: 1990/91 to 1999/2000 10-4-1990 The thI acan, 1990-10-04 Ithaca College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1990-91 Recommended Citation Ithaca College, "The thI acan, 1990-10-04" (1990). The Ithacan, 1990-91. 6. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1990-91/6 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The thI acan: 1990/91 to 1999/2000 at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The thI acan, 1990-91 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. • ~ I :ii Ithaca. wetlands' construction Fairyland shattered by adminis Midnight Oil gives held Up tration indecisiveness anticlimactic performance .•• page 6 ... page 7 ... page 9 ,, ... ,,1,'-•y•'• ,,1. :CJ<,·')• ..... The ITHACAN The Newspaper For The Ithaca College Community Vol. 58, No. 6 October 4, 1990 24 pages Free Arrests. conti:n-ue despite warning lcm." 'crackdown' on parties on South neighborhoods. 75 student arrests over--past three weeks Dave Maley, Manager of Public Hill. McEwen said that he needs at "I expect students to think of this By Joe Porletto Holt, head of the IC office of cam Information for IC, said that when least one additional officer, but there area as their home," McEwen said. The weekend of Sept. 28 resulted pus"' safety, addressed the party students are off-campus they must isn't room in the city budget for it McEwen said that studcn ts wouldn't in 26 arrests of college students on proolem. -

Anastasia Bauer the Use of Signing Space in a Shared Signing Language of Australia Sign Language Typology 5

Anastasia Bauer The Use of Signing Space in a Shared Signing Language of Australia Sign Language Typology 5 Editors Marie Coppola Onno Crasborn Ulrike Zeshan Editorial board Sam Lutalo-Kiingi Irit Meir Ronice Müller de Quadros Roland Pfau Adam Schembri Gladys Tang Erin Wilkinson Jun Hui Yang De Gruyter Mouton · Ishara Press The Use of Signing Space in a Shared Sign Language of Australia by Anastasia Bauer De Gruyter Mouton · Ishara Press ISBN 978-1-61451-733-7 e-ISBN 978-1-61451-547-0 ISSN 2192-5186 e-ISSN 2192-5194 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. ” 2014 Walter de Gruyter, Inc., Boston/Berlin and Ishara Press, Lancaster, United Kingdom Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Țȍ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Acknowledgements This book is the revised and edited version of my doctoral dissertation that I defended at the Faculty of Arts and Humanities of the University of Cologne, Germany in January 2013. It is the result of many experiences I have encoun- tered from dozens of remarkable individuals who I wish to acknowledge. First of all, this study would have been simply impossible without its partici- pants. The data that form the basis of this book I owe entirely to my Yolngu family who taught me with patience and care about this wonderful Yolngu language. -

Let's Face It, the 1980'S Were Responsible for Some Truly Horrific

80sX Let’s face it, the 1980’s were responsible for some truly horrific crimes against fashion: shoulder-pads, leg-warmers, the unforgivable mullet ! What’s evident though, now more than ever, is that the 80’s provided us with some of the best music ever made. It doesn’t seem to matter if you were alive in the 80’s or not, those songs still resonate with people and trigger a joyous reaction for anyone that hears them. Auckland band 80sX take the greatest new wave, new romantic and synth pop hits and recreate the magic and sounds of the 80’s with brilliant musicianship and high energy vocals. Drummer and programmer Andrew Maclaren is the founding member of multi platinum selling band stellar* co-writing mega hits 'Violent', 'All It Takes' and 'Taken' amongst others. During those years he teamed up with Tom Bailey from iconic 80’s band The Thompson Twins to produce three albums, winning 11 x NZ music awards, selling over 100,000 albums and touring the world. Andrew Thorne plays lead guitar and brings a wealth of experience to 80’sX having played all the guitars on Bic Runga’s 11 x platinum debut album ‘Drive’. He has toured the world with many of New Zealand’s leading singer songwriter’s including Bic, Dave Dobbyn, Jan Hellriegel, Tim Finn and played support for international acts including Radiohead, Bryan Adams and Jeff Buckley. Bass player Brett Wells is a Chartered Director and Executive Management Professional with over 25 years operations experience in Webb Group (incorporating the Rockshop; KBB Music; wholesale; service and logistics) and foundation member of the Board. -

Alexis Wright's Carpentaria and the Swan Book

Exchanges: The Interdisciplinary Research Journal Climate Fiction and the Crisis of Imagination: Alexis Wright’s Carpentaria and The Swan Book Chiara Xausa Department of Interpreting and Translation, University of Bologna, Italy Correspondence: [email protected] Peer review: This article has been subject to a Abstract double-blind peer review process This article analyses the representation of environmental crisis and climate crisis in Carpentaria (2006) and The Swan Book (2013) by Indigenous Australian writer Alexis Wright. Building upon the groundbreaking work of environmental humanities scholars such as Heise (2008), Clark (2015), Copyright notice: This Trexler (2015) and Ghosh (2016), who have emphasised the main article is issued under the challenges faced by authors of climate fiction, it considers the novels as an terms of the Creative Commons Attribution entry point to address the climate-related crisis of culture – while License, which permits acknowledging the problematic aspects of reading Indigenous texts as use and redistribution of antidotes to the 'great derangement’ – and the danger of a singular the work provided that the original author and Anthropocene narrative that silences the ‘unevenly universal’ (Nixon, 2011) source are credited. responsibilities and vulnerabilities to environmental harm. Exploring You must give themes such as environmental racism, ecological imperialism, and the slow appropriate credit violence of climate change, it suggests that Alexis Wright’s novels are of (author attribution), utmost importance for global conversations about the Anthropocene and provide a link to the license, and indicate if its literary representations, as they bring the unevenness of environmental changes were made. You and climate crisis to visibility. -

Mick Evans Song List 1

MICK EVANS SONG LIST 1. 1927 If I could 2. 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Here Without You 3. 4 Non Blondes What’s Going On 4. Abba Dancing Queen 5. AC/DC Shook Me All Night Long Highway to Hell 6. Adel Find Another You 7. Allan Jackson Little Bitty Remember When 8. America Horse with No Name Sister Golden Hair 9. Australian Crawl Boys Light Up Reckless Oh No Not You Again 10. Angels She Keeps No Secrets from You MICK EVANS SONG LIST Am I Ever Gonna See Your Face Again 11. Avicii Hey Brother 12. Barenaked Ladies It’s All Been Done 13. Beatles Saw Her Standing There Hey Jude 14. Ben Harper Steam My Kisses 15. Bernard Fanning Song Bird 16. Billy Idol Rebel Yell 17. Billy Joel Piano Man 18. Blink 182 Small Things 19. Bob Dylan How Does It Feel 20. Bon Jovi Living on a Prayer Wanted Dead or Alive Always Bead of Roses Blaze of Glory Saturday Night MICK EVANS SONG LIST 21. Bruce Springsteen Dancing in the dark I’m on Fire My Home town The River Streets of Philadelphia 22. Bryan Adams Summer of 69 Heaven Run to You Cuts Like A Knife When You’re Gone 23. Bush Glycerine 24. Carly Simon Your So Vein 25. Cheap Trick The Flame 26. Choir Boys Run to Paradise 27. Cold Chisel Bow River Khe Sanh When the War is Over My Baby Flame Trees MICK EVANS SONG LIST 28. Cold Play Yellow 29. Collective Soul The World I know 30. Concrete Blonde Joey 31. -

Lobby Loyde: the G.O.D.Father of Australian Rock

Lobby Loyde: the G.O.D.father of Australian rock Paul Oldham Supervisor: Dr Vicki Crowley A thesis submitted to The University of South Australia Bachelor of Arts (Honours) School of Communication, International Studies and Languages Division of Education, Arts, and Social Science Contents Lobby Loyde: the G.O.D.father of Australian rock ................................................. i Contents ................................................................................................................................... ii Table of Figures ................................................................................................................... iv Abstract .................................................................................................................................. ivi Statement of Authorship ............................................................................................... viiiii Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................. ix Chapter One: Overture ....................................................................................................... 1 Introduction: Lobby Loyde 1941 - 2007 ....................................................................... 2 It is written: The dominant narrative of Australian rock formation...................... 4 Oz Rock, Billy Thorpe and AC/DC ............................................................................... 7 Private eye: Looking for Lobby Loyde ......................................................................... -

![[Download] Midnight 13](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2541/download-midnight-13-532541.webp)

[Download] Midnight 13

[PDF-a03]Midnight 13 Midnight 13 Midnight Oil - Wikipedia Dexys Midnight Runners - Wikipedia The Midnight Website Sun, 28 Oct 2018 04:02:00 GMT Midnight Oil - Wikipedia Midnight Oil (known informally as "The Oils") are an Australian rock band composed of Peter Garrett (vocals, harmonica), Rob Hirst (drums), Jim Moginie (guitar, keyboard), Martin Rotsey (guitar) and Bones Hillman (bass guitar). The group was formed in Sydney in 1972 by Hirst, Moginie and original bassist Andrew James as Farm: they enlisted Garrett the following year, changed their name in 1976 ... Dexys Midnight Runners - Wikipedia Dexys Midnight Runners (currently officially Dexys, their former nickname, styled without an apostrophe) are an English pop band with soul influences, who achieved their major success in the early to mid-1980s. They are best known in the UK for their songs "Come On Eileen" and "Geno", both of which peaked at No. 1 on the UK Singles Chart, as well as six other top-20 singles. [Download] Midnight 13 The Midnight Website Midnight were formed in 2003, inspired by the magical sound of Blackmore's Night.The choice to be called "Midnight" is not accidental: "midnight" is a metaphor not only of a past time, but also a "mysterious elsewhere" the magic hour of the night for excellence, where fairies and elves dance in the woods, the wizards prepare their spells and the witches gather under a large walnut tree. pdf Download Midnight Club 2 on Steam The world's most notorious drivers meet each night on the streets of LA, Paris, and Tokyo. Choose from a collection of performance-enhanced cars or bikes and compete head-to-head to make a name for yourself. -

A World-Ecological Reading of Drought in Thea Astley's

humanities Article Dry Country, Wet City: A World-Ecological Reading of Drought in Thea Astley’s Drylands Ashley Cahillane Discipline of English, National University of Ireland, Galway, Ireland; [email protected] Received: 6 January 2020; Accepted: 16 July 2020; Published: 11 August 2020 Abstract: Using a postcolonial and world-ecological framework, this article analyses the representation of water as an energy source in Thea Astley’s last and most critically acclaimed novel Drylands (1999). As environmental historians have argued, the colonial, and later capitalist, settlement of Australia, particularly the arid interior, was dependent on securing freshwater sources—a historical process that showed little regard for ecological impact or water justice until recent times. Drylands’ engagement with this history will be considered in relation to Michael Cathcart’s concept of ‘water dreaming’ (2010): the way in which water became reimagined after colonization to signify the prospect of economic growth and the consolidation of settler belonging. Drylands self-consciously incorporates predominant modes of ‘water dreaming’ into its narrative, yet resists reducing water to a passive resource. This happens on the level of both content and form: while its theme of drought-induced migration is critical of the past, present, and future social and ecological effects of the reckless extraction of freshwater, its nonlinear plot and hybrid form as a montage of short stories work to undermine the dominant anthropocentric colonial narratives that underline technocratic water cultivation. Keywords: Australian literature; world-ecology; blue humanities; world literature; ecocriticism; postcolonial ecocriticism 1. Introduction Water dictates Australia’s ecology, economy, and culture. Though surrounded by water, Australia is the world’s driest inhabited continent. -

ABR Favourite Australian Novels

Announcing the top ten ABR Favourite Australian Novels Of the 290 individual novels that were nominated in the ABR FAN Poll, below we list the top ten. At the foot of page 25 we simply name the ten titles that followed. We don’t have room to list all of your favourites. A complete alphabetical listing now appears on our website: www.australian- bookreview.com – a fillip to further reading and to a deeper appreciation of the range of Australian fiction, which was our shy hope when we polled our readers. Cloudstreet im Winton’s books attract international kudos, pres- 1 tigious awards and massive sales. Winton won the Australian/Vogel National Award with his first novel andT last year became only the second person to win the Miles Franklin Award four times. Cloudstreet, published in 1991, holds a unique place in Australian readers’ affections. Winton’s tale of the Lambs and the Pickles from the end of World War II to the 1960s won the 1992 Miles Franklin Award and was dramatised by Nick Enright and Justin Monjo. Presciently, in 1994, The Oxford Companion to Australian Literature predicted that ‘it seems certain to establish itself as one of Australia’s best novels’. Countless voters agreed. One of them, Carla Ziino, described it as ‘the quintessential Australian novel’. The Fortunes Voss of Richard atrick White, 2 3 Australia’s first Mahony Nobel Laureate Pfor Literature, dominat- enry Handel’s ed Australian literature grand trilogy from the 1950s to his – Australia death in 1990. Voss, his HFelix (1917), The Way fifth novel, published Home (1925) and Ultima in 1957, won the first Thule (1929), first col- Miles Franklin Award. -

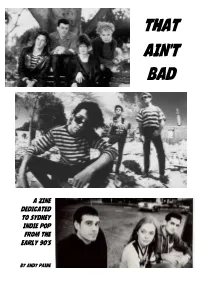

That Ain't Bad (The Main Single Off Tingles), the Band Are Drowned out by the Crowd Singing Along

THAT AIN’T BAD A ZINE DEDICATED TO SYDNEY INDIE POP FROM THE EARLY 90’S BY ANDY PAINE INTROduction In the late 1980's and early 1990's, a group of bands emerged from Sydney who all played fuzzy distorted guitars juxtaposed with poppy melodies and harmonies. They released some wonderful music, had a brief period of remarkable mainstream success, and then faded from the memory of Australia's 'alternative' music world. I was too young to catch any of this music the first time around – by the time I heard any of these bands the 90’s were well and truly over. It's hard to say how I first heard or heard about the bands in this zine. As a teenage music nerd I devoured the history of music like a mechanical harvester ploughing through a field of vegetables - rarely pausing to stop and think, somethings were discarded, some kept with you. I discovered music in a haphazard way, not helped by living in a country town where there were few others who shared my passion for obscure bands and scenes. The internet was an incredible resource, but it was different back then too. There was no wikipedia, no youtube, no streaming, and slow dial-up speeds. Besides the net, the main ways my teenage self had access to alternative music was triple j and Saturday nights spent staying up watching guest programmers on rage. It was probably a mixture of all these that led to me discovering what I am, for the purposes of this zine, lumping together as "early 90's Sydney indie pop". -

1MI Suite Honeymoon TAKE IT DOES WHAT 1986 7, June Bowie David 11 No

- 42996-J - Chrysalis - - 78-16424-P Atlantic - AL8-8212-N Arista AS1-9466-N Arista Foster David Device ATTACK Houston Whitney Houston Whitney FOSTER DAVID HEART A ON HANGING HOUSTON WHITNEY ALL OF LOVE GREATEST PICK ALBUM PICK SINGLE ALBUM No.1 SINGLE No.1 7 -Page Walkabout. -John Newton Olivia & offering, latest the discusses and album Foster David their over label with Phantoms' their ME OF BEST THE dis-illusionment band's the expresses Fixx, The of Woods, Adam Drummer Stewart Rod 11111111111111111111111111111.111111111 TOUCH LOVE Late Be To Seger Bob Time In Just ROCK A LIKE EYE EYE Bangles Emotional WANTS SHE WHAT OSBORNE JEFFREY KNEW SHE IF Boy Animal Noise Of Art RAMONES GUNN PETER Children Without Palmer Robert Or With You Of Those ON YOU TURN COSBY BILL TO MEAN DIDN'T I Debarge El DeBarge El DEBARGE EL JOHNNY WHO'S Shooz Nu Control WAIT CAN'T I WATCH TO JACKSON JANET ALBUMS Gabriel Peter Replay Action SLEDGEHAMMER JONES HOWARD Special 38 One To One Silence Visible NIGHT OTHER NO In POCKET MY IN ANGEL LIKE NOISE OF ART THE Hooters Jones Howard Zone Love BLAME TO IS ONE NO GO CHILDREN OCEAN BILLY THE DO WHERE Red Simply Franklin Aretha Book Picture YEARS THE BACK HOLDING RED SIMPLY YOU LOVED McDonald Michael & EVER NOBODY AIN'T Required Jacket No LaBelle Patti COLLINS PHIL Thunderbirds Fabulous OWN MY ON ENUFF TUFF Rush Jennifer Michael George RUST, Nicks Stevie JENNIFER CORNER DIFFERENT A YOU WRITTEN EVER ANYONE HAS ALBUMS HOT"'" 44, 'be Nil 1MI Suite Honeymoon TAKE IT DOES WHAT 1986 7, June Bowie David 11 No.