Campbell V. Air Jamaica Ltd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Air Jamaica Report

OFFICE OF THE CONTRACTOR GENERAL Special Report of Investigation and Monitoring Conducted into the Procurement Practices of Air Jamaica Limited (Formerly) Ministry of Finance and Planning EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The investigation into the Procurement and Contract award practices of Air Jamaica Limited was initiated by the Office of the Contractor General (OCG) on 2006 May 23. On 2006 May 16, the Office of the Contractor General received a letter from Mrs. Sharon Weber, who wrote on behalf of the Financial Secretary in the Ministry of Finance and Planning. The letter confirmed that Air Jamaica Limited was a Public Body by virtue of the Government’s one hundred percent (100%) ownership as stipulated by Part 1 (Section 2) of the Public Bodies Management and Accountability Act, 2001. Air Jamaica Limited has been through ownership changes over the last 15 years. Most recently - in 2004 December - the airline was reacquired by the Government of Jamaica following almost a decade of privately managed operations. Consequently, Air Jamaica Limited, as of 2004 December, is deemed to be a ‘public body’ as defined within the Contractor General Act (1983) and is required to adhere to the Government Procurement Guidelines. The investigation of the entity focused primarily on procurement activities between May 2005 and August 2008 and incorporated the OCG’s monitoring of the airline’s procurement activities up to, and including, August 2008. The period under review commences approximately six months after Air Jamaica Limited returned to the ambits of government control. It is perceived that this period should have provided the agency with some amount of __________________________________________________________________________________________ Air Jamaica Investigation Office of the Contractor-General 2008 September Page 1 of 33 time to acclimatize itself with stipulated government policies, thereby effecting a smooth transition from a private to a public entity as it relates to procurement practices. -

Export Guide to the Consumer Food Market September 1997 Prepared for the U.S. Department of Agriculture by Fintrac Inc

Haiti Export Guide to the Consumer Food Market September 1997 Prepared for the U.S. Department of Agriculture by Fintrac Inc. This guide is one of ten individual guides available (not including a summary guide), covering the following countries and territories: Aruba and Curacao; the Bahamas; Barbados; British Territories, comprising Anguilla, the British Virgin Islands, the Cayman Islands, and the Turks and Caicos; the Dominican Republic; Guadeloupe and Martinique; Haiti; Jamaica; and the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States, comprising Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Grenada, St. Kitts-Nevis, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines. For more information, contact USDA/FAS offices in the Dominican Republic and Miami: Kevin Smith, Agricultural Counselor (for the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, and Haiti) Mailing Address: American Embassy Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic (FAS) Unit 5530 APO AA 34041 Other Mailing Address: Leopoldo Navarro #1 Apt. 4 Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic Tel: 809-688-8090 Fax: 809-685-4743 e-mail: [email protected] . Margie Bauer, Director (for all other countries covered by these guides) Mailing Address: Caribbean Basin Agricultural Trade Office USDA/FAS 909 SE 1st Avenue, Suite 720 Miami, FL 33131 Tel: 305-536-5300 Fax: 305-536-7577 e-mail: [email protected] List of Abbreviations Used BVI British Virgin Islands CARICOM Caribbean Community (comprised of Antigua & Barbuda, the Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Haiti, Jamaica, Montserrat, St. Kitts-Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Vincent & the -

Community Relations Plan

Miami International Airport Community Relations Plan Preface .............................................................................................................. 1 Overview of the CRP ......................................................................................... 2 NCP Background ............................................................................................... 3 National Contingency Plan .............................................................................................................. 3 Government Oversight.................................................................................................................... 4 Site Description and History ............................................................................. 5 Site Description .............................................................................................................................. 5 Site History .................................................................................................................................... 5 Goals of the CRP ............................................................................................... 8 Community Relations Activities........................................................................ 9 Appendix A – Site Map .................................................................................... 10 Appendix B – Contact List............................................................................... 11 Federal Officials .......................................................................................................................... -

Airlines Codes

Airlines codes Sorted by Airlines Sorted by Code Airline Code Airline Code Aces VX Deutsche Bahn AG 2A Action Airlines XQ Aerocondor Trans Aereos 2B Acvilla Air WZ Denim Air 2D ADA Air ZY Ireland Airways 2E Adria Airways JP Frontier Flying Service 2F Aea International Pte 7X Debonair Airways 2G AER Lingus Limited EI European Airlines 2H Aero Asia International E4 Air Burkina 2J Aero California JR Kitty Hawk Airlines Inc 2K Aero Continente N6 Karlog Air 2L Aero Costa Rica Acori ML Moldavian Airlines 2M Aero Lineas Sosa P4 Haiti Aviation 2N Aero Lloyd Flugreisen YP Air Philippines Corp 2P Aero Service 5R Millenium Air Corp 2Q Aero Services Executive W4 Island Express 2S Aero Zambia Z9 Canada Three Thousand 2T Aerocaribe QA Western Pacific Air 2U Aerocondor Trans Aereos 2B Amtrak 2V Aeroejecutivo SA de CV SX Pacific Midland Airlines 2W Aeroflot Russian SU Helenair Corporation Ltd 2Y Aeroleasing SA FP Changan Airlines 2Z Aeroline Gmbh 7E Mafira Air 3A Aerolineas Argentinas AR Avior 3B Aerolineas Dominicanas YU Corporate Express Airline 3C Aerolineas Internacional N2 Palair Macedonian Air 3D Aerolineas Paraguayas A8 Northwestern Air Lease 3E Aerolineas Santo Domingo EX Air Inuit Ltd 3H Aeromar Airlines VW Air Alliance 3J Aeromexico AM Tatonduk Flying Service 3K Aeromexpress QO Gulfstream International 3M Aeronautica de Cancun RE Air Urga 3N Aeroperlas WL Georgian Airlines 3P Aeroperu PL China Yunnan Airlines 3Q Aeropostal Alas VH Avia Air Nv 3R Aerorepublica P5 Shuswap Air 3S Aerosanta Airlines UJ Turan Air Airline Company 3T Aeroservicios -

Concept Paper Air Transport

CARIBBEAN COMMUNITY CONCEPT PAPER STRATEGIC PLAN FOR AIR TRANSPORT SERVICES IN CARICOM January 11, 2009 El Perial Management Services CARIBBEAN COMMUNITY CONCEPT PAPER STRATEGIC PLAN FOR AIR TRANSPORT SERVICES IN CARICOM Table of Contents The Air Transport Imperative …………………………………………………01 Air Transport Demand…………………………………………………………03 Overview of the Air Transport Sector…………………………………………06 Strengthening The Regional Airlines………………………………………….14 Recommendations……………………………………………………………..18 CONCEPT PAPER STRATEGIC PLAN FOR AIR TRANSPORT SERVICES IN CARICOM This Concept Paper has been commissioned by the CARICOM Secretariat to be presented at a Regional symposium to develop the “Elements of the Strategic Vision for Services Sector Development in the Caribbean Community (CARICOM)”. As a start the paper has to understand the level of need for efficient air transport services in the CARICOM Region (Region). THE AIR TRANSPORT IMPERATIVE The paper recognises that CARICOM is: • a grouping of small sovereign countries, mainly islands with small populations and open economies, that rarely enjoy economies of scale • characterised by separation by water which seems to negatively impact cooperative attitudes and behaviour • a large geographic area; the distance between Suriname in South America and Belize in Central America is c.a. 2081 nautical miles or a flying time of c.a. 4hrs 20mins by jet aircraft. • regularly afflicted by hurricanes that adversely impact infrastructure, primary industries (tourism and agriculture) and already limited government resources • is heavily dependent upon air transport as the Year 2007 visitor arrival statistics in Appendix A show • in the early stages of implementing the CARICOM Single Market (CSM) aspect of the CARICOM Single Market and Economy (CSME) which forms the central theme of the 2001 CARICOM Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas. -

Analysis of the Interaction Between Air Transportation and Economic Activity: a Worldwide Perspective

ANALYSIS OF THE INTERACTION BETWEEN AIR TRANSPORTATION AND ECONOMIC ACTIVITY: A WORLDWIDE PERSPECTIVE Mariya A. Ishutkina and R. John Hansman This report is based on the Doctoral Dissertation of Mariya A. Ishutkina submitted to the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The work presented in this report was also conducted in collaboration with the members of the Doctoral Committee: Prof. R. John Hansman (Chair) Prof. John D. Sterman Prof. Ian A. Waitz Report No. ICAT-2009-2 March 2009 MIT International Center for Air Transportation (ICAT) Department of Aeronautics & Astronautics Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, MA 02139 USA Analysis of the Interaction Between Air Transportation and Economic Activity: A Worldwide Perspective by Mariya A. Ishutkina Submitted to the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics on March 11, 2009, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Abstract Air transportation usage and economic activity are interdependent. Air transportation provides employment and enables certain economic activities which are dependent on the availability of air transportation services. The economy, in turn, drives the demand for air transportation services resulting in the feedback relationship between the two. The objective of this work is to contribute to the understanding of the relationship between air transportation and economic activity. More specifically, this work seeks to (1) develop a feedback model to describe the relationship between air transportation and economic activity and (2) identify factors which stimulate or suppress air transportation development. To achieve these objectives this work uses an exploratory research method which combines literature review, aggregate data and case study analyses. -

STATEMENT by the PRIME MINISTER, HON BRUCE GOLDING RESPONSE to EARTHQUAKE TRAGEDY in HAITI in the HOUSES of PARLIAMENT Tuesday, January 19, 2010

STATEMENT BY THE PRIME MINISTER, HON BRUCE GOLDING RESPONSE TO EARTHQUAKE TRAGEDY IN HAITI IN THE HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT Tuesday, January 19, 2010 Jamaica, as, indeed, people throughout the world, were horrified by the terrible tragedy that befell the people of Haiti following the massive earthquake last Tuesday. Television coverage of the aftermath, the collapsed buildings, the dead bodies lying amidst the rubble, the frantic efforts to reach those still trapped beneath tons of concrete, the agony on the faces of the thousands who have lost loved ones, who writhe in pain from their injuries, not knowing when they will be attended to, whose houses have been destroyed and who have gone for days without food and water, tell the grim tale of the extent of the suffering of a people who have experienced so much human tragedy in their lives but never anything of this magnitude. The authorities have been forced to bury the dead in hurriedly-dug mass graves without identification or even photographs. Many Haitians will never be able to bring closure to their grief; they will never know with certainty what happened to their mothers and fathers, their sons and daughters, brothers and sisters. Prime Minister Jean-Max Bellerive told me last Thursday that so far they had been forced to bury 7,000 people in this unceremonious way. It is reported that by Sunday, that number had risen to 70,000! The final death toll, still unknown, is likely to be considerably more than that. The response of the international community has been swift and strong. -

Annual Report 2011 - 2012

airports authority of jamaica Thinking Development . Moving Ahead ANNUAL REPORT 2011 - 2012 AIRPORT HISTORY, VISION, MISSION AND CORPORATE VALUES AIRPORT HISTORY The Airports Authority of Jamaica (AAJ) was established in 1974, under the Airports Authority Act as an independent statutory body to manage and operate both the Norman Manley International (NMIA) and Sangster International (SIA) Airports. In 1990 the AAJ was given the operational responsibility for the four domestic aerodromes namely; Tinson Pen in Kingston, Ken Jones in Portland, Boscobel in St Mary and Negril in Westmoreland. Sangster International Airport was privatised in April 2003 and is now operated by MBJ Airports Limited (a private consortium) under a thirty-year concession agreement with the AAJ. NMIA Airports Ltd (NMIAL) , a wholly owned subsidiary of AAJ, was established in October 2003, as the airport operator for the Norman Manley International Airport under a thirty-year concession agreement with the AAJ. In 2011 a third International Port of Entry was established, the Ian Fleming International Airport, through the upgrading of the Boscobel Aerodrome to accommodate and process international passengers. airports authority of jamaica 1 VISION STATEMENT “To build and sustain a world-class airport system, which facilitates private investment and partnership and positions Jamaica’s airports as the gateway to the Caribbean and the Americas.” MISSION STATEMENT “To develop a modern, safe and profitable airport system that is environmentally responsible, provides world-class service, and contributes substantially to the national economy while promoting the expansion of air transportation and its related industries.” airports authority of jamaica 2 In an atmosphere of honesty, fairness, and integrity, we commit to our core organizational values – People, Customer Focus, Integrity, Financial Management, Regulatory and Statutory Requirements, Safety and Security and Environment. -

Caribbean Airlines Takes Delivery of Its First ATR 72-600

Toulouse, 9 November 2011 Caribbean Airlines takes delivery of its first ATR 72-600 Trinidad and Tobago’s national flag carrier will start replacing its ageing fleet of Bombardier Q-300s and adding frequencies, routes and passenger capacity Caribbean Airlines today took delivery in Toulouse of its first ATR 72-600 aircraft. The Port-of-Spain-based carrier, which becomes one of the very first operators of the new ‘ATR -600 series’, booked earlier this year a US$ 200 million-valued contract for the purchase of a total of 9 of these aircraft. The aircraft are configured with 68 seats and equipped with the new ATR -600s standards of comfort, including In-Flight Entertainment. With this new ATR 72-600 delivered today, Caribbean Airlines will start replacing its fleet of five 50-seat Q-300s and introducing newest and most technologically advanced turboprops into its domestic routes. The airline will also add passenger capacity and develop new routes and frequencies within Trinidad and Tobago. Caribbean Airlines will also operate some of its new ATR 72-600s in the domestic route network of Air Jamaica, which was recently acquired by Trinidad and Tobago’s flag carrier. ATR is well established in the Latin American and Caribbean region, with some 140 aircraft in operation, plus more than 60 on order. Commenting on today’s first delivery, Robert Corbie, Acting Chief Executive Officer of Caribbean Airlines declared: “The introduction of this very first ATR 72-600 aircraft marks a real milestone in our national aviation. It represents the arrival of the most modern and cost-efficient regional turboprop aircraft into our country. -

BACKGROUND Delta Airlines Is an Innovative, Creative Company and a Well-Established and Res Pected Airline

BACKGROUND Delta Airlines is an innovative, creative company and a well-established and res pected airline. It is also the oldest and largest air passenger carrier in the w orld as at September 2009, after acquiring NorthWest Airlines. Since its incepti on in 1928 Delta has built a reputation of offering consistent superior customer service to its passengers. For four decades, Delta held the reputation of being the most consistently profitable airline, however with the US Federal Airline D eregulation Act of 1978, coupled with the recession of early 1980s saw the Airli ne suffering its first financial loss in the early 1980s. The company however managed to turn the defeat around and was again profitable w ell into the 1990s. Delta constantly faced challenges - economic downturns, comp etition from low cost carriers (domestic) and other international airlines compe ting for US international travellers. By the time Delta entered the 21st century it was faced with new challenges; such as the crippling of the airline industry in 2001 - a direct result of the terrorist attacks of September 11th, the const antly rising fuel prices, and the economic downturn in 2009. Delta eventually fi led for bankruptcy in 2005, when it was no longer able to meet its financial obl igations. Industry analysts typify the airline industry as unattractive, unstable and cycl ical in nature. Delta operates in an intensely competitive environment, which is still struggling to recover from the most recent recession. Efforts to compete with low cost carriers have not met with expectations. A pioneer of the hub and spoke model which it uses to map its destinations, Delta‘s competitive edge is bei ng the airline of choice for international travel. -

Nextpage Livepublish

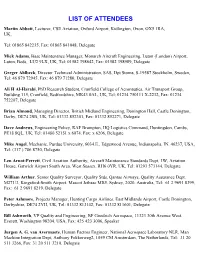

LIST OF ATTENDEES Martin Abbott, Lecturer, CSE Aviation, Oxford Airport, Kidlington, Oxon, OX5 1RA, UK, Tel: 01865 842235, Fax: 01865 841048, Delegate Mick Adams, Base Maintenance Manager, Monarch Aircraft Engineering, Luton (London) Airport, Luton, Beds, LU2 9LX, UK, Tel: 01582 398642, Fax: 01582 398989, Delegate Greger Ahlbeck, Director Technical Administration, SAS, Dpt Stoma, S-19587 Stockholm, Sweden, Tel: 46 879 72945, Fax: 46 879 71280, Delegate Ali H Al-Harabi, PhD Research Student, Cranfield College of Aeronautics, Air Transport Group, Building 115, Cranfield, Bedfordshire, MK43 0AL, UK, Tel: 01234 750111 X-2232, Fax: 01234 752207, Delegate Brian Almond, Managing Director, British Midland Engineering, Donington Hall, Castle Donington, Derby, DE74 2SB, UK, Tel: 01332 852301, Fax: 01332 852271, Delegate Dave Andrews, Engineering Policy, RAF Brampton, HQ Logistics Command, Huntingdon, Cambs, PE18 8QL, UK, Tel: 01480 52151 x 6074, Fax: x 6206, Delegate Mike Angel, Mechanic, Purdue University, 6034.E., Edgewood Avenue, Indianapolis, IN. 46237, USA, Tel: (317 ) 786 8750, Delegate Len Arnot-Perrett, Civil Aviation Authority, Aircraft Maintenance Standards Dept, 1W, Aviation House, Gatwick Airport South Area, West Sussex, RH6 0YR, UK, Tel: 01293 573144, Delegate William Arthur, Senior Quality Surveyor, Quality Stds, Qantas Airways, Quality Assurance Dept. M271/3, Kingsford-Smith Airport, Mascot Jetbase MB5, Sydney, 2020, Australia, Tel: 61 2 9691 8399, Fax: 61 2 9691 8219, Delegate Peter Ashmore, Projects Manager, Hunting Cargo Airlines, East Midlands Airport, Castle Donington, Derbyshire, DE74 2YH, UK, Tel: 01332 813142, Fax: 01332 811601, Delegate Bill Ashworth, VP Quality and Engineering, BF Goodrich Aerospace, 11323 30th Avenue West, Everett, Washington 98204, USA, Fax: 425 423 3006, Speaker Jurgen A. -

Cooperative Agreements Involving Foreign Airlines: a Review of the Policy of the United States Civil Aeronautics Board Burton A

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 35 | Issue 4 Article 3 1969 Cooperative Agreements Involving Foreign Airlines: A Review of the Policy of the United States Civil Aeronautics Board Burton A. Landy Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Burton A. Landy, Cooperative Agreements Involving Foreign Airlines: A Review of the Policy of the United States Civil Aeronautics Board, 35 J. Air L. & Com. 575 (1969) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol35/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. COOPERATIVE AGREEMENTS INVOLVING FOREIGN AIRLINES: A REVIEW OF THE POLICY OF THE UNITED STATES CIVIL AERONAUTICS BOARD* By BURTON A. LANDYt I. INTRODUCTION T RADITIONALLY, the airline industry has been highly individualistic. Today's air carriers, almost without exception, are the product of these individualistic pioneering efforts. Yet, during the current decade, there has been a notable trend "to band together" rather than the tradi- tional "go it alone" approach. A manifestation of this trend to join up was the merger movement of the early 1960's. This characteristic was due in large part to the poor financial condition of many of the airlines. As the jet transition took place and the financial health of the airlines improved, the merger wave subsided for a time, and the airlines seemed to return to their usual, independent way of doing business.