ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: FOLKLORISTIC and ETHNIC INFLUENCES in SELECTED VIOLIN REPERTOIRE: a STUDY of MUSIC INSPIRED by S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flint Orchestra

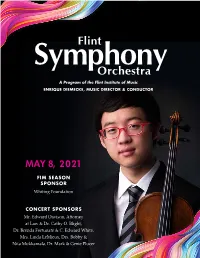

Flint SymphonyOrchestra A Program of the Flint Institute of Music ENRIQUE DIEMECKE, MUSIC DIRECTOR & CONDUCTOR MAY 8, 2021 FIM SEASON SPONSOR Whiting Foundation CONCERT SPONSORS Mr. Edward Davison, Attorney at Law & Dr. Cathy O. Blight, Dr. Brenda Fortunate & C. Edward White, Mrs. Linda LeMieux, Drs. Bobby & Nita Mukkamala, Dr. Mark & Genie Plucer Flint Symphony Orchestra THEFSO.ORG 2020 – 21 Season SEASON AT A GLANCE Flint Symphony Orchestra Flint School of Performing Arts Flint Repertory Theatre STRAVINSKY & PROKOFIEV FAMILY DAY SAT, FEB 6, 2021 @ 7:30PM Cathy Prevett, narrator SAINT-SAËNS & BRAHMS SAT, MAR 6, 2021 @ 7:30PM Noelle Naito, violin 2020 William C. Byrd Winner WELCOME TO THE 2020 – 21 SEASON WITH YOUR FLINT SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA! BEETHOVEN & DVOŘÁK SAT, APR 10, 2021 @ 7:30PM he Flint Symphony Orchestra (FSO) is one of Joonghun Cho, piano the finest orchestras of its size in the nation. BRUCH & TCHAIKOVSKY TIts rich 103-year history as a cultural icon SAT, MAY 8, 2021 @ 7:30PM in the community is testament to the dedication Julian Rhee, violin of world-class performance from the musicians AN EVENING WITH and Flint and Genesee County audiences alike. DAMIEN ESCOBAR The FSO has been performing under the baton SAT, JUNE 19, 2021 @ 7:30PM of Maestro Enrique Diemecke for over 30 years Damien Escobar, violin now – one of the longest tenures for a Music Director in the country. Under the Maestro’s unwavering musical integrity and commitment to the community, the FSO has connected with audiences throughout southeast Michigan, delivering outstanding artistry and excellence. All dates are subject to change. -

A History of British Music Vol 1

A History of Music in the British Isles Volume 1 A History of Music in the British Isles Other books from e Letterworth Press by Laurence Bristow-Smith e second volume of A History of Music in the British Isles: Volume 1 Empire and Aerwards and Harold Nicolson: Half-an-Eye on History From Monks to Merchants Laurence Bristow-Smith The Letterworth Press Published in Switzerland by the Letterworth Press http://www.eLetterworthPress.org Printed by Ingram Spark To © Laurence Bristow-Smith 2017 Peter Winnington editor and friend for forty years ISBN 978-2-9700654-6-3 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 Contents Acknowledgements xi Preface xiii 1 Very Early Music 1 2 Romans, Druids, and Bards 6 3 Anglo-Saxons, Celts, and Harps 3 4 Augustine, Plainsong, and Vikings 16 5 Organum, Notation, and Organs 21 6 Normans, Cathedrals, and Giraldus Cambrensis 26 7 e Chapel Royal, Medieval Lyrics, and the Waits 31 8 Minstrels, Troubadours, and Courtly Love 37 9 e Morris, and the Ballad 44 10 Music, Science, and Politics 50 11 Dunstable, and la Contenance Angloise 53 12 e Eton Choirbook, and the Early Tudors 58 13 Pre-Reformation Ireland, Wales, and Scotland 66 14 Robert Carver, and the Scottish Reformation 70 15 e English Reformation, Merbecke, and Tye 75 16 John Taverner 82 17 John Sheppard 87 18 omas Tallis 91 19 Early Byrd 101 20 Catholic Byrd 108 21 Madrigals 114 22 e Waits, and the eatre 124 23 Folk Music, Ravenscro, and Ballads 130 24 e English Ayre, and omas Campion 136 25 John Dowland 143 26 King James, King Charles, and the Masque 153 27 Orlando Gibbons 162 28 omas -

Download (1MB)

BYRON'S LETTERS AND JOURNALS Byron's Letters and Journals A New Selection From Leslie A. Marchand's twelve-volume edition Edited by RICHARD LANSDOWN OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, ox2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © In the selection, introduction, and editorial matter Richard Lansdown 2015 © In the Byron copyright material John Murray 1973-1982 The moral rights of the author have be en asserted First Edition published in 2015 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publicationmay be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writi ng of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press i98 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2014949666 ISBN 978-0-19-872255-7 Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives pk in memory of Dan Jacobson 1929-2014 'no one has Been & Done like you' ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Two generations of Byron scholars, biographers, students, and readers have acknowledged the debt they owe to Professor Leslie A. -

Rep List 1.Pub

Richmond Symphony Orchestra League Student Concerto Competition Repertoire Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Guitar & percussion students are welcome to participate; Please contact Anne Hoffler, contest coordinator, at aahoffl[email protected] for repertoire approval no later than November 30. VIOLIN Faure Elegy, Op. 24 Bach All Violin concerti Haydn Cello Concerto No. 1 in C major Beethoven Violin Concerto in D major Haydn Cello Concerto No. 2 in D major Beethoven Romance No. 1 in G major Kabalevsky Cello Concerto No. 1 in G minor, Op. 49 Beethoven Romance No. 2 in F major Lalo Cello Concerto in D minor Bériot Scéne de Ballet, Op. 100 Rubinstein Cello Concerto No. 2 in D minor, Op.96 Bériot Violin Concerto No. 7 in G major Saint-Saëns Cello Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Op.33 Bériot Violin Concerto No. 9 in A minor Saint-Saëns Cello Concerto No. 2 in D minor, Op. 119 Bruch Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor Schumann Cello Concerto in A minor Haydn All Violin concerti Shostakovich Concerto for Cello No. 1 Kabalevsky Violin Concerto in C Major, Op. 48 Stamitz All Cello concerti Lalo Symphonie Espagnole R. Strauss Romanze in F major Massenet Méditation from Thaïs Tchaikovsky Variations on a Rococo Theme, Op.33 Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Op.64 Vivaldi All Cello concerti Mozart Violin Concerto No. 1 in B-flat major Mozart Violin Concerto No. 2 in D major BASS Mozart Violin Concerto No. 3 in G major Bottesini Double Bass Concerto No.2 in B minor Mozart Violin Concerto No. -

String Diplomas Repertoire List

String diplomas repertoire list 1 January 2011 – 31 December 2018 STRING DIPLOMAS 2011–2018 Contents Page LCM Publications ........................................................................................................................ 2 Overview of LCM Diploma Structure ................................................................................. 3 Violin DipLCM in Performance .......................................................................................................... 4 ALCM in Performance .............................................................................................................. 5 LLCM in Performance ............................................................................................................... 7 FLCM in Performance ............................................................................................................... 7 Viola DipLCM in Performance .......................................................................................................... 8 ALCM in Performance .............................................................................................................. 9 LLCM in Performance ............................................................................................................... 10 FLCM in Performance ............................................................................................................... 11 Cello DipLCM in Performance ......................................................................................................... -

Wichita Symphony Youth Orchestras Acceptable Repertoire for Youth Talent Auditions

Wichita Symphony Youth Orchestras Acceptable Repertoire for Youth Talent Auditions Repertoire not listed below may be acceptable, but must be pre-approved. Contact Tiffany Bell at [email protected] to request approval for repertoire not on this list. Violin Bach: Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Bach: Concerto No. 2 in E Major Barber: Concerto, Op. 14, first movement Beethoven: Concerto in D Major, Op. 61 Beethoven: Romance No. 1 in G Major Beethoven: Romance No. 2 in F Major Brahms: Concerto, third movement Bruch: Concerto No. 1 in G Minor, Op. 26, any movement Bruch: Scottish Fantasy Conus: Concerto in E Minor, first movement Dvorak: Romance Haydn: Concerto in C Major, Hob.VIIa Kabalevsky: Concerto, Op. 48, first or third movement Khachaturian: Violin Concert, Allegro Vivace, first movement Lalo: Symphonie Espagnole, first or fifth movement Mendelssohn: Concerto in E Minor, any movement Mozart: Concerto No. 3 in G Major, K. 216, any movement Mozart: Concerto No. 4 in D Major, K. 218, first movement Mozart: Concerto No. 5 in A Major, K. 219, first movement Saint-Saens: Introduction and Rondo Capriccios, Op. 28 Saint-Saens: Concerto No. 3 in B Minor, Op. 61 Saint-Saens: Havanaise Sarasate: Zigeunerweisen, Op. 20 Sibelius: Concerto in D Minor, fist movement Tchaikovsky: Concerto, third movement Vitali: Chaconne Wieniawski: Legend, Op. 17 Wieniawski: Concerto in D Minor Viola J.C. Bach/Casadesus: Concerto in C Minor, Adagio-Allegro Bach: Concerto in D Minor, first movement Forsythe: Concerto for Viola, first movement Handel/Casadesus: Concerto in B Minor Hoffmeister Concerto Stamitz: Concerto in D Major Telemann: Concerto in G Major Cello Boccherini: Concerto Bruch: Kol Nidrei Dvorak: Concerto in B Minor, Op. -

Universiv Micrcsilms International

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. Tlie sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

Scottish Fantasy

JOSHUA BELL BRUCH Scottish Fantasy Academy of St Martin in the Fields Br uc h (1838-1920) SCOTTISH FANTASY FOR VIOLIN AND ORCHESTRA, OP. 46 1 I. Introduction: Grave, Adagio cantabile 2 II. Scherzo: Allegro 3 III. Andante sostenuto 4 IV. Finale: Allegro guerriero VIOLIN CONCERTO NO. 1 IN G MINOR, OP. 26 5 I. Vorspiel: Allegro moderato 6 II. Adagio 7 III. Finale: Allegro energico Joshua Bell, Soloist/Director Academy of St Martin in the Fields Master of More than Melody The works presented here are two out of the three pieces by Max Bruch that can be called staples of the classical repertoire. (The third is his piece for cello and orchestra, Kol Nidrei.) In his lifetime he was best known for large-scale choral works, well received at their premieres and popular with the many amateur choral societies found throughout Europe in the later 19th century. Those choruses began to dwindle once the 20th century got underway. As they disappeared, Bruch’s cantatas and oratorios also faded from consciousness, rarely, if ever, to be heard again. By association, Bruch became thought of as a composer whose time had come and gone. It is interesting to compare the very diff erent assessments of him in two successive editions of Grove’s Dictionary of Music, from 1904 and 1954. The earlier edition declared: “He is above all a master of melody, and of the eff ective treatment of masses of sound.” By 1954 the verdict on his output was dismissive and condescending: ‘It is its lack of adventure that limited its fame.’ Bruch was born during the lifetimes of Mendelssohn and Schumann and died when Schoenberg and Stravinsky were creating gigantic waves in musical life. -

Dissertation Final Submission Andy Hillhouse

TOURING AS SOCIAL PRACTICE: TRANSNATIONAL FESTIVALS, PERSONALIZED NETWORKS, AND NEW FOLK MUSIC SENSIBILITIES by Andrew Neil Hillhouse A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto © Copyright by Andrew Neil Hillhouse (2013) ABSTRACT Touring as Social Practice: Transnational Festivals, Personalized Networks, and New Folk Music Sensibilities Andrew Neil Hillhouse Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto 2013 The aim of this dissertation is to contribute to an understanding of the changing relationship between collectivist ideals and individualism within dispersed, transnational, and heterogeneous cultural spaces. I focus on musicians working in professional folk music, a field that has strong, historic associations with collectivism. This field consists of folk festivals, music camps, and other venues at which musicians from a range of countries, affiliated with broad labels such as ‘Celtic,’ ‘Nordic,’ ‘bluegrass,’ or ‘fiddle music,’ interact. Various collaborative connections emerge from such encounters, creating socio-musical networks that cross boundaries of genre, region, and nation. These interactions create a social space that has received little attention in ethnomusicology. While there is an emerging body of literature devoted to specific folk festivals in the context of globalization, few studies have examined the relationship between the transnational character of this circuit and the changing sensibilities, music, and social networks of particular musicians who make a living on it. To this end, I examine the career trajectories of three interrelated musicians who have worked in folk music: the late Canadian fiddler Oliver Schroer (1956-2008), the ii Irish flute player Nuala Kennedy, and the Italian organetto player Filippo Gambetta. -

THE WEEK at a GLANCE Yahrzeits

THE WEEK AT A GLANCE ENRICHING LIVES THROUGH COMMUNITY, Sunday, 7/1 ~ 18 Tammuz 8:00 am Morning Service (with Torah reading for Fast), Homestead Hebrew Chapel LIFELONG JEWISH LEARNING, & SPIRITUAL GROWTH Fast of Tammuz (dawn to dark) 7:00 pm Evening Service, Helfant Chapel 7:30 am Morning Service, Homestead Hebrew Chapel Monday, 7/2 ~ 19 Tammuz 9:00 am Talmud Study, 61C Café, 1839 Murray Avenue 7:00 pm Evening Service, Helfant Chapel Shabbat Shalom! 7:30 am Morning Service, Homestead Hebrew Chapel Tuesday, 7/3 ~ 20 Tammuz 7:00 pm Evening Service, Helfant Chapel 17 Tammuz, 5778 Wednesday, 7/4 ~ 21 Tammuz parashah Balak. 8:00 am Morning Service, Homestead Hebrew Chapel This week’s is Independence Day 7:00 pm Evening Service, Helfant Chapel Office closed. 7:30 am Morning Service, Homestead Hebrew Chapel Thursday, 7/5 ~ 22 Tammuz 7:00 pm Evening Service, Helfant Chapel Friday, 7/6 ~ 23 Tammuz 7:30 am Morning Service, Homestead Hebrew Chapel Candle lighting 8:34 pm 5:45 pm Shababababa and Shabbat Haverim, Samuel and Minnie Hyman Ballroom 6:00 pm Kabbalat Shabbat, Helfant Chapel Friday, June 29, 2018 6:30 am Early Morning Shabbat Service, Homestead Hebrew Chapel 9:30 am Shabbat Service, Helfant Chapel Candle lighting 8:36 pm Saturday, 7/7 ~ 24 Tammuz 10:00 am Youth Tefillah, Youth Lounge, then Lehman Center and Eisner Commons Havdalah 9:34 pm 12:15 pm Congregational Kiddush, Palkovitz Lobby 8:35 pm Minhah, Discussion, Ma’ariv, Homestead Hebrew Chapel Kabbalat Shabbat 6:00 pm Helfant Chapel Yahrzeits FOR THE WEEK OF JUNE 30 - JULY 6, 2018 17 - 23 TAMMUZ, 5778 The following Yahrzeits will be observed today and in the coming week. -

Medieval Music for Celtic Harp Pdf Free Download

MEDIEVAL MUSIC FOR CELTIC HARP PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Star Edwards | 40 pages | 01 Jan 2010 | Mel Bay Publications | 9780786657339 | English | United States Medieval Music for Celtic Harp PDF Book Close X Learn about Digital Video. Unde et ibi quasi fontem artis jam requirunt. An elegy to Sir Donald MacDonald of Clanranald, attributed to his widow in , contains a very early reference to the bagpipe in a lairdly setting:. In light of the recent advice given by the government regarding COVID, please be aware of the following announcement from Royal Mail advising of changes to their services. The treble end had a tenon which fitted into the top of the com soundbox. Emer Mallon of Connla in action on the Celtic Harp. List of Medieval composers List of Medieval music theorists. Adam de la Halle. Detailed Description. Monophony was replaced from the fourteenth century by the Ars Nova , a movement that developed in France and then Italy, replacing the restrictive styles of Gregorian plainchant with complex polyphony. Allmand, T. Browse our Advice Topics. Location: optional. The urshnaim may refer to the wooden toggle to which a string was fastened once it had emerged from its hole in the soundboard. Password recovery. The early history of the triangular frame harp in Europe is contested. This word may originally have described a different stringed instrument, being etymologically related to the Welsh crwth. Also: Alasdair Ross discusses that all the Scottish harp figures were copied from foreign drawings and not from life, in 'Harps of Their Owne Sorte'? One wonderful resource is the Session Tunes. -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} History and the Morris Dance: a Look

HISTORY AND THE MORRIS DANCE: A LOOK AT MORRIS DANCING FROM ITS EARLIEST DAYS UNTIL 1850 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dr. John Cutting | 204 pages | 31 Jan 2010 | Dance Books Ltd | 9781852731083 | English | Hampshire, United Kingdom Modern dance | Britannica Cunningham, who would have turned this year, would sometimes flip a coin to decide the next move, giving his work a nonlinear, collagelike quality. These were ideas simultaneously being explored in visual art, which was engaged in a similar resetting of boundaries as Pop, Minimalism and conceptual art replaced Abstract Expressionism, with which modern dance was closely aligned; for one, both were preoccupied with working on the floor, as in the paintings of Jackson Pollock and the dances of Martha Graham. Postmodernists remained keen on gravity, however. Certain choreographers would come to treat the floor as a dance partner, just as multidisciplinary artists like Ana Mendieta and Bruce Nauman used it in their performance pieces as a site for symbolic regeneration or heady writhing. Forti considered her work as much dance as sculpture, its human performers art objects like any other — but it hardly mattered, since, for this brief and exceptional window, art, dance and music were almost synonymous. The s New York art scene was famously small, and disciplines blended together as a result. In time, though, the moment of equilibrium passed and the community collapsed, reality itself acting as a sort of score. After the last Judson dance concert in , Childs taught elementary school for five years to support herself before returning to the field. Forti lived for a time in Rome, crossing paths with the Arte Povera movement, and Deborah Hay eventually landed in Austin, where she hosted group workshops.