Achron a MESSAGE from the MILKEN ARCHIVE FOUNDER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recollections from a Life in Music

Syracuse University SURFACE The Courier Libraries Spring 1985 Recollections from a Life in Music Louis Krasner Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Krasner, Louis. "Recollections from a Life in Music." The Courier 20.1 (1985): 9-18. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES COURIER VOLUME XX, NUMBER 1, SPRING 1985 SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES COURIER VOLUME XX NUMBER ONE SPRING 1985 Foresight and Courage: A Tribute to Louis Krasner by Howard Boatwright, Professor of Music, 3 Syracuse University Recollections from a Life in Music by Louis Krasner, Professor Emeritus of Music, 9 Syracuse University; and Instructor of Violin, New England Conservatory of Music Unusual Beethoven Items from the Krasner Collection by Donald Seibert, Music Bibliographer, 19 Syracuse University Libraries Alvaro,Agustfn de Liano and His Books in Leopold von Ranke's Library by Gail P. Hueting, Librarian, University of Illinois 31 at Urbana,Champaign Lady Chatterley's Lover: The Grove Press Publication of the Unexpurgated Text by Raymond T. Caffrey, New York University 49 Benson Lossing: His Life and Work, 1830,1860 by Diane M. Casey, Syracuse University 81 News of the Syracuse University Libraries and the Library Associates 97 Recollections from a Life in Music BY LOUIS KRASNER On October 28, 1984, Mr. Krasner came back to his old home, Syr, acuse University, in order to speak to the Ubrary Associates at their an, nual meeting. -

Complete Catalogue 2006 Catalogue Complete

COMPLETE CATALOGUE 2006 COMPLETE CATALOGUE Inhalt ORFEO A – Z............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Recital............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................82 Anthologie ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................89 Weihnachten ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................96 ORFEO D’OR Bayerische Staatsoper Live ...................................................................................................................................................................................................99 Bayreuther Festspiele Live ...................................................................................................................................................................................................109 -

Otto Klemperer Curriculum Vitae

Dick Bruggeman Werner Unger Otto Klemperer Curriculum vitae 1885 Born 14 May in Breslau, Germany (since 1945: Wrocław, Poland). 1889 The family moves to Hamburg, where the 9-year old Otto for the first time of his life spots Gustav Mahler (then Kapellmeister at the Municipal Theatre) out on the street. 1901 Piano studies and theory lessons at the Hoch Conservatory, Frankfurt am Main. 1902 Enters the Klindworth-Scharwenka Conservatory in Berlin. 1905 Continues piano studies at Berlin’s Stern Conservatory, besides theory also takes up conducting and composition lessons (with Hans Pfitzner). Conducts the off-stage orchestra for Mahler’s Second Symphony under Oskar Fried, meeting the composer personally for the first time during the rehearsals. 1906 Debuts as opera conductor in Max Reinhardt’s production of Offenbach’s Orpheus in der Unterwelt, substituting for Oskar Fried after the first night. Klemperer visits Mahler in Vienna armed with his piano arrangement of his Second Symphony and plays him the Scherzo (by heart). Mahler gives him a written recommendation as ‘an outstanding musician, predestined for a conductor’s career’. 1907-1910 First engagement as assistant conductor and chorus master at the Deutsches Landestheater in Prague. Debuts with Weber’s Der Freischütz. Attends the rehearsals and first performance (19 September 1908) of Mahler’s Seventh Symphony. 1910 Decides to leave the Jewish congregation (January). Attends Mahler’s rehearsals for the first performance (12 September) of his Eighth Symphony in Munich. 1910-1912 Serves as Kapellmeister (i.e., assistant conductor, together with Gustav Brecher) at Hamburg’s Stadttheater (Municipal Opera). Debuts with Wagner’s Lohengrin and conducts guest performances by Enrico Caruso (Bizet’s Carmen and Verdi’s Rigoletto). -

Universiv Micrcsilms International

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. Tlie sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

SCHOENBERG Violin Concerto a Survivor from Warsaw Rolf Schulte, Violin • David Wilson-Johnson, Narrator Simon Joly Chorale • Philharmonia Orchestra Robert Craft

557528 bk Schoenberg 8/18/08 4:10 PM Page 12 SCHOENBERG Violin Concerto A Survivor from Warsaw Rolf Schulte, Violin • David Wilson-Johnson, Narrator Simon Joly Chorale • Philharmonia Orchestra Robert Craft Available from Naxos Books 8.557528 12 557528 bk Schoenberg 8/18/08 4:10 PM Page 2 THE ROBERT CRAFT COLLECTION Robert Craft THE MUSIC OF ARNOLD SCHOENBERG, Vol. 10 Robert Craft, the noted conductor and widely respected writer and critic on music, literature, and culture, holds a Robert Craft, Conductor unique place in world music of today. He is in the process of recording the complete works of Stravinsky, Schoenberg, and Webern for Naxos. He has twice won the Grand Prix du Disque as well as the Edison Prize for his landmark recordings of Schoenberg, Webern, and Varèse. He has also received a special award from the American Academy and 1 A Survivor from Warsaw National Institute of Arts and Letters in recognition of his “creative work” in literature. In 2002 he was awarded the for Narrator, Men’s Chorus and Orchestra, Op. 46 7:11 International Prix du Disque Lifetime Achievement Award, Cannes Music Festival. Robert Craft has conducted and recorded with most of the world’s major orchestras in the United States, Europe, David Wilson-Johnson, Narrator • Simon Joly Chorale • Philharmonia Orchestra Russia, Japan, Korea, Mexico, South America, Australia, and New Zealand. He is the first American to have conducted Berg’s Wozzeck and Lulu, and his original Webern album enabled music lovers to become acquainted with this Recorded at Abbey Road Studio One, London, on 3rd October, 2007 composer’s then little-known music. -

THE WEEK at a GLANCE Yahrzeits

THE WEEK AT A GLANCE ENRICHING LIVES THROUGH COMMUNITY, Sunday, 7/1 ~ 18 Tammuz 8:00 am Morning Service (with Torah reading for Fast), Homestead Hebrew Chapel LIFELONG JEWISH LEARNING, & SPIRITUAL GROWTH Fast of Tammuz (dawn to dark) 7:00 pm Evening Service, Helfant Chapel 7:30 am Morning Service, Homestead Hebrew Chapel Monday, 7/2 ~ 19 Tammuz 9:00 am Talmud Study, 61C Café, 1839 Murray Avenue 7:00 pm Evening Service, Helfant Chapel Shabbat Shalom! 7:30 am Morning Service, Homestead Hebrew Chapel Tuesday, 7/3 ~ 20 Tammuz 7:00 pm Evening Service, Helfant Chapel 17 Tammuz, 5778 Wednesday, 7/4 ~ 21 Tammuz parashah Balak. 8:00 am Morning Service, Homestead Hebrew Chapel This week’s is Independence Day 7:00 pm Evening Service, Helfant Chapel Office closed. 7:30 am Morning Service, Homestead Hebrew Chapel Thursday, 7/5 ~ 22 Tammuz 7:00 pm Evening Service, Helfant Chapel Friday, 7/6 ~ 23 Tammuz 7:30 am Morning Service, Homestead Hebrew Chapel Candle lighting 8:34 pm 5:45 pm Shababababa and Shabbat Haverim, Samuel and Minnie Hyman Ballroom 6:00 pm Kabbalat Shabbat, Helfant Chapel Friday, June 29, 2018 6:30 am Early Morning Shabbat Service, Homestead Hebrew Chapel 9:30 am Shabbat Service, Helfant Chapel Candle lighting 8:36 pm Saturday, 7/7 ~ 24 Tammuz 10:00 am Youth Tefillah, Youth Lounge, then Lehman Center and Eisner Commons Havdalah 9:34 pm 12:15 pm Congregational Kiddush, Palkovitz Lobby 8:35 pm Minhah, Discussion, Ma’ariv, Homestead Hebrew Chapel Kabbalat Shabbat 6:00 pm Helfant Chapel Yahrzeits FOR THE WEEK OF JUNE 30 - JULY 6, 2018 17 - 23 TAMMUZ, 5778 The following Yahrzeits will be observed today and in the coming week. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 2004

2004, Tanglewood to SEIJI O ZAWA HALL Prelude Concert lOth ANNIVERSARY SEASON Friday, August 27, at 6 Florence Gould Auditorium, Seiji Ozawa Hall TANGLEWOOD FESTIVAL CHORUS JOHN OLIVER, conductor with FRANK CORLISS and MARTIN AMLIN, pianists FENWICK SMITH, flute ANN HOBSON PILOT, harp Texts and Translations Translations by Laura Mennill and Michal Kohout RHHr3 LEOS JANACEK (1854-1928) !!2£9@& Three Mixed Choruses P£yt£fr&iMi Pisen v jeseni Song of Autumn Nuz vzhuru k vysinam! Then up at heights! Cim jsou mi vazby tela? Whose is my textured body? HfMM Ja neznam zhynuti. I don't know death. V*$R 9 Ja neznam smrti chlad, I don't know cold death, A4S&2I Mne jest, )ak hudba sfer I feel like a sphere of music by nad mou hlavou znela, sounds above my head. Ja letim hvezdam vstric na bile peruti. I fly to meet the star on white wings. Ma duse na vlnach jak kvet buji, My soul on waves as flowers grow wild, z ni vune, laska ma se vznasi vys a vys, from its odor, my love floats higher and higher, kol moje myslenky se toci, poletuji, how much my thoughts roll, fly, jak pestfi motyli, like a colorful butterfly, ku hvezdam bliz a bliz! towards the star nearer and nearer! Ma duse paprsek, My soul beams, se v modrem vzduchu houpa, in the blue air sways, vidi, co sni kvet see, what dreams flower na dne v svem kalichu, at the bottom of its goblet, cim trtina zastena, what reeds shield, kdyz bfe hu vlna skoupa as the waves hit the shores ji usty vlhkymi chce zlibat potichu. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 93, 1973-1974

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEIJI OZAWA Music Director COLIN DAVIS & MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS Principal Guest Conductors NINETY-THIRD SEASON 1973-1974 FRIDAY-SATURDAY 6 CAMBRIDGE 2 THE TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. TALCOTT M. BANKS President PHILIP K. ALLEN ROBERT H. GARDINER JOHN L. THORNDIKE Vice-President Vice-President Treasurer VERNON R. ALDEN MRS HARRIS FAHNESTOCK MRS JAMES H. PERKINS ALLEN G. BARRY HAROLD D. HODGKINSON IRVING W. RABB MRS JOHN M. BRADLEY E. MORTON JENNINGS JR PAUL C. REARDON RICHARD P. CHAPMAN EDWARD M. KENNEDY MRS GEORGE LEE SARGENT ABRAM T. COLLIER EDWARD G. MURRAY SIDNEY STONEMAN ARCHIE C. EPPS III JOHN T. NOONAN JOHN HOYT STOOKEY TRUSTEES EMERITUS HENRY B. CABOT HENRY A. LAUGHLIN PALFREY PERKINS FRANCIS W. HATCH EDWARD A. TAFT ADMINISTRATION OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA THOMAS D. PERRY JR THOMAS W. MORRIS Executive Director Manager MARY H. SMITH JOHN H. CURTIS Concert Manager Public Relations Director FORRESTER C. SMITH DANIEL R. GUSTIN RICHARD C. WHITE Development Director Administrator of Assistant to Educational Affairs the Manager DONALD W. MACKENZIE JAMES F. KILEY Operations Manager, Operations Manager, Symphony Hall Tanglewood HARRY NEVILLE Program Editor copyright © 1973 by Boston Symphony Orchestra Inc. SYMPHONY HALL BOSTON MASSACHUSETTS %ftduy .Or Furs labeled to show country of origin. BOSTON -CHESTNUT HILL'NORTHSHORE SHOPPING CENTER'SOUTH SHORE PLAZA' BURLINGTON MALL' WELLESLEY CONTENTS Program for November 9, 10 and 13 1973 287 Future programs Friday-Saturday series 327 Tuesday Cambridge series 329 Program notes Schoenberg- Violin concerto op. 36 by Michael Steinberg 289 A Reminiscence of the Premiere by Louis Krasner 295 Tchaikovsky -Symphony no. -

Download the Programme (PDF

Sunday 19 January 2020 7–9.05pm Thursday 13 February 2020 7.30–9.35pm Barbican LSO SEASON CONCERT CHRIST ON THE MOUNT OF OLIVES Berg Violin Concerto Interval Beethoven Christ on the Mount of Olives Sir Simon Rattle conductor Lisa Batiashvili violin Elsa Dreisig soprano Pavol Breslik tenor David Soar bass London Symphony Chorus Simon Halsey chorus director Part of Beethoven 250 at the Barbican Thursday 13 February 2020 broadcast live on BBC Radio 3 Welcome Latest News On Our Blog will be recorded for LSO Live, the Orchestra DONATELLA FLICK LSO LUNAR NEW YEAR PREMIERES: is also joined by the full force of the London CONDUCTING COMPETITION LSO DISCOVERY COMPOSERS Symphony Chorus, led by Chorus Director PAST AND PRESENT Simon Halsey. Applications are now open for the 16th Donatella Flick LSO Conducting Competition Following a sold-out debut in January 2019, Berg’s Violin Concerto opens these concerts, in 2021, founded in 1990 by Donatella Flick artist collective Tangram return to LSO St for which we welcome soloist Lisa Batiashvili, and celebrating its 30th anniversary this year. Luke’s on 25 January to interweave folk who first performed with the Orchestra on the melodies with brand-new compositions. Barbican stage in 2006, and has appeared • lso.co.uk/more/news We caught up with composers Raymond Yiu, regularly in recent years. We look forward to Jasmin Kent Rodgman and Alex Ho – all LSO Lisa Batiashvili joining us on tour for further Discovery composers of past and present warm welcome to these LSO performances of this concerto in Europe. -

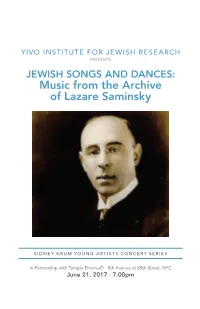

Music from the Archive of Lazare Saminsky

YIVO INSTITUTE FOR JEWISH RESEARCH PRESENTS JEWISH SONGS AND DANCES: Music from the Archive of Lazare Saminsky SIDNEY KRUM YOUNG ARTISTS CONCERT SERIES In Partnership with Temple Emanu-El · 5th Avenue at 65th Street, NYC June 21, 2017 · 7:00pm PROGRAM The Sidney Krum Young Artists Concert Series is made possible by a generous gift from the Estate of Sidney Krum. In partnership with Temple Emanu-El. Saminsky, Hassidic Suite Op. 24 1-3 Saminsky, First Hebrew Song Cycle Op. 12 1-3 Engel, Omrim: Yeshnah erets Achron, 2 Hebrew Pieces Op. 35 No. 2 Saminsky, Second Hebrew Song Cycle Op. 13 1-3 Saminsky, A Kleyne Rapsodi Saminsky, And Rabbi Eliezer Said Engel, Rabbi Levi-Yitzkah’s Kaddish Achron, Sher Op. 42 Saminsky, Lid fun esterke Saminsky, Shir Hashirim Streicher, Shir Hashirim Engel, Freylekhs, Op. 21 Performers: Mo Glazman, Voice Eliza Bagg, Voice Brigid Coleridge, Violin Julian Schwartz, Cello Marika Bournaki, Piano COMPOSER BIOGRAPHIES Born in Vale-Gotzulovo, Ukraine in 1882, LAZARE SAMINSKY was one of the founding members of the Society for Jewish Folk Music in St. Petersburg – a group of composers committed to forging a new national style of Jewish classical music infused with Jewish folk melodies and liturgical music. Saminksy’s teachers at the St. Petersburg conservatory included Rimsky-Korsakov and Liadov. Fascinated with Jewish culture, Saminsky went on trips to Southern Russia and Georgia to gather Jewish folk music and ancient religious chants. In the 1910s Saminsky spent a substantial amount of time travelling giving lectures and conducting concerts. Saminsky’s travels brought him to Turkey, Syria, Palestine, Paris, and England. -

Cello Concerto (1990)

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET CONCERTOS A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Edited by Stephen Ellis Composers A-G RUSTAM ABDULLAYEV (b. 1947, UZBEKISTAN) Born in Khorezm. He studied composition at the Tashkent Conservatory with Rumil Vildanov and Boris Zeidman. He later became a professor of composition and orchestration of the State Conservatory of Uzbekistan as well as chairman of the Composers' Union of Uzbekistan. He has composed prolifically in most genres including opera, orchestral, chamber and vocal works. He has completed 4 additional Concertos for Piano (1991, 1993, 1994, 1995) as well as a Violin Concerto (2009). Piano Concerto No. 1 (1972) Adiba Sharipova (piano)/Z. Khaknazirov/Uzbekistan State Symphony Orchestra ( + Zakirov: Piano Concerto and Yanov-Yanovsky: Piano Concertino) MELODIYA S10 20999 001 (LP) (1984) LEV ABELIOVICH (1912-1985, BELARUS) Born in Vilnius, Lithuania. He studied at the Warsaw Conservatory and then at the Minsk Conservatory where his composition teacher was Vasily Zolataryov. After graduation from the latter institution, he took further composition courses with Nikolai Miaskovsky at the Moscow Conservatory. He composed orchestral, vocal and chamber works. Piano Concerto in E minor (1976) Alexander Tutunov (piano)/ Marlan Carlson/Corvallis-Oregon State University Symphony Orchestra ( + Piano Trio, Aria for Viola and Piano and 10 Romances) ALTARUS 9058 (2003) Aria for Violin and Chamber Orchestra (1973) Mikhail Shtein (violin)/Alexander Polyanko/Minsk Chamber Orchestra ( + Vagner: Clarinet Concerto and Alkhimovich: Concerto Grosso No. 2) MELODIYA S10 27829 003 (LP) (1988) MusicWeb International Last updated: August 2020 Russian, Soviet & Post-Soviet Concertos A-G ISIDOR ACHRON (1891-1948) Piano Concerto No. -

Romantic Voices Danbi Um, Violin; Orion Weiss, Piano; with Paul Huang, Violin

CARTE BLANCHE CONCERT IV: Romantic Voices Danbi Um, violin; Orion Weiss, piano; with Paul Huang, violin July 30 PROGRAM OVERVIEW Violinist Danbi Um embodies the tradition of the great Romantic style, her Sunday, July 30 natural vocal expression coupled with virtuosic technique. Partnered by pia- 6:00 p.m., Stent Family Hall, Menlo School nist Orion Weiss, making his Music@Menlo debut, she offers a program of music she holds closest to her heart, a stunning variety of both favorites and SPECIAL THANKS delightful discoveries. Music@Menlo dedicates this performance to Hazel Cheilek with gratitude for her generous support. ERNEST BLOCH (1880–1959) JENŐ HUBAY (1858–1937) Violin Sonata no. 2, Poème mystique (1924) Scènes de la csárda no. 3 for Violin and Piano, op. 18, Maros vize (The River GEORGE ENESCU (1881–1955) Maros) (ca. 1882–1883) Violin Sonata no. 3 in a minor, op. 25, Dans le caractère populaire roumain (In FRITZ KREISLER (1875–1962) Romanian Folk Character) (1926) Midnight Bells (after Richard Heuberger’s Midnight Bells from Moderato malinconico The Opera Ball) (1923) Andante sostenuto e misterioso Allegro con brio, ma non troppo mosso ERNEST BLOCH Avodah (1928) INTERMISSION JOSEPH ACHRON (1886–1943) ERICH WOLFGANG KORNGOLD (1897–1957) Hebrew Dance, op. 35, no. 1 (1913) Four Pieces for Violin and Piano from the Incidental Music to Shakespeare’s CONCERTS BLANCHE CARTE Danbi Um, violin; Orion Weiss, piano Much Ado about Nothing, op. 11 (1918–1919) Maiden in the Bridal Chamber March of the Watch PABLO DE SARASATE (1844–1908) Intermezzo: Garden Scene Navarra (Spanish Dance) for Two Violins and Piano, op.