Building Cities, Building Worlds: Cities in Play

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Christmas Store Card Back3

DONATiONS NEEDED BABiES Blankets, activity center/ baby gym, sleepers, crib toys, clothes and bibs, crib mobiles, car seat toys 1-3 YEAR OLDS Large trucks and cars, baby dolls (all ethnicities), doll accessories (bottles, etc), sensory books, musical toys, building blocks, soft dolls, Little Tykes items, Little People items, Fisher-Price toys, educational toys, stuffed animals 4-5 YEAR OLDS Board games for young children, Lincoln Logs, Tinkertoys, doll house with accessories, Hot Wheels tracks and cars, stuffed animals, wooden train sets, Nerf balls, plastic tool sets, art supplies, musical instruments, kitchen play sets, children’s books, dolls and accessories, Play-Doh, plastic animals, Tonka-type cars, and trucks, puzzles 1ST-3RD GRADERS Barbie dolls (all ethnicities), Barbie doll accessories, action figures, traditional board games, card games (i.e. Uno, Skip-bo, etc), art supplies and sets, Beanie Babies, baby dolls and accessories, 18” dolls and accessories (i.e. American Girl Doll-size), hand-held games (non-violent), children’s books, Polly Pocket / Polly Fashion sets, remote control vehicles (w/ batteries), Hot Wheels cars and track, basketballs (intermediate 28.5), footballs (youth size), soccer balls (size 4 or 5), cooking sets 4TH-6TH GRADERS Remote control vehicles, baseball, bat and glove, basketballs (28.5 & 29.5), footballs, soccer balls (size 5), sports equipment, Legos, jewelry, DVD players, brain teasers / puzzle mania, chapter books, art supplies, craft kits TEENAGERS DVD players, makeup, body glitter, etc., cologne gift sets, sports equipment (full size), jewelry, purses, gift sets (bath, hair, nails), hoodies, iPods, headphones / earbuds, art supplies (pencils, drawing pads), remote control vehicles (w/ batteries), Xbox, PlayStation, Wii games (non-violent), wallets, winter hats, scarves, fun socks RiDiNG TOYS (NEW ONLY) Tricycles, bicycles (all sizes), preschool riding toys, scooters, ripsticks, skateboards, longboards, skates, helmets (all sizes) $15 Walmart Gift Cards CHRiSTMAS STORE VOLUNTEERS NEEDED BiRCHMAN.ORG. -

Discontinue Use of Toys Immediately

IMPORTANT VOLUNTARY PRODUCT RECALL INFORMATION One product recalled for impermissible levels of lead November 2006 magnet recall expanded DISCONTINUE USE OF TOYS IMMEDIATELY Thank you for responding to the voluntary product recall by Mattel® (NZ). Please note, the affected “CARS” die-cast vehicle assortment line was manufactured between March 2007 and July 2007. The toy in question is a green army vehicle known as “Sarge”. The affected car may have been sold alone or as part of an assortment containing Sarge cars. Surface paints on the car may contain increased levels of lead, which if ingested, may have health ramifications. The recalled car is marked on the bottom with ‘7EA’. Sarge Cars or Assortments containing Sarge Cars have the following Model Numbers on the package: H6414, M1253 or L6294. The affected products are marked “China”. There have been no reports of injuries involving the affected product in New Zealand or overseas. Additionally, Mattel® is voluntarily recalling magnetic toys manufactured between January 2002 and January 31, 2007 including certain dolls, figures, play sets and accessories that may release small, powerful magnets. The recall expands upon Mattel®’s voluntary recall of eight toys in November 2006 and is based on a thorough internal review of all Mattel® brands. Mattel® is exercising caution and has expanded the list of recalled magnetic toys due to potential safety risks associated with toys that might contain loose magnets. Beginning in January 2007, Mattel® implemented enhanced magnet retention systems in its toys across all brands. Consumers should immediately take the recalled toys away from children. Please review the following images and descriptions affected by these recalls, indicating the total number of toys you own in the space next to the image. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

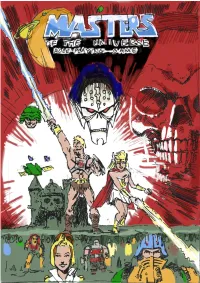

Creating a Character

This game is based on Mattel's Masters of the Universe. It would be nothing without the many people involved in creating the brand and everything connected to it. I've tried to acknowledge everyone that I know had a part but there's bound to be omissions. Thanks to everyone involved. A brand as large as this is not easy to wrap one's head around and while there's only one writer of this game most of the information here was originally collected by fans and shared on various websites, mailing lists and forums. I owe a great gratitude to all those people and I've tried to credit everyone but there might be people I've neglected to mention. I'd be happy to correct any mistakes, and change online aliases to the correct names if you wish. This is version 0.4 MOTU RPG created by Daniel Schenström Masters of the Universe Classics (MOTUC) entries in this game mostly written by Scott Neitlich and Danielle Gelehrter. Masters of the Universe created and expanded by: Roger Sweet, Mark Taylor, Ted Mayer, Tony Guerro, Donald F. Glut, Alfredo Alcala, Colin Bailey, Michael Halperin, Bruce Timm, Tim Kilpin, Lou Scheimer, Dave Capper, Alan Tyler, Ed Watts, Mark Jones, James McElroy, Mike McKittrick, William George, Dave Maurer, Jim Keifer, Dave Wolfram, Stephen Lee, Scott Neitlich, Val Staples, Emiliano Santalucia, Josh Van Pelt, James Eatock, Robert Lamb, David Wise, Paul Dini, Larry DiTillio, J. Michael Stracszynski, Rowby Goren, Warren Greenwood, Gary Cohn, George Caragonne, Ron Wilson, Evelyn Stein, Thanks to: he-man.org, The Power and Honor Foundation, Mattel, Patrick Fogarty, the He-man wiki, Illustrations by: Daniel Schenström Two images are extensions and baed off of Filmation animation background plates. -

Product Recalls, Imperfect Information, and Spillover Effects: Lessons from the Consumer Response to the 2007 Toy Recalls

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES PRODUCT RECALLS, IMPERFECT INFORMATION, AND SPILLOVER EFFECTS: LESSONS FROM THE CONSUMER RESPONSE TO THE 2007 TOY RECALLS Seth M. Freedman Melissa Schettini Kearney Mara Lederman Working Paper 15183 http://www.nber.org/papers/w15183 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 July 2009 We gratefully acknowledge the helpful comments of Severin Borenstein, Jonathan Guryan, Judy Hellerstein, Ginger Jin, Arik Levinson, Soohyung Lee, Nuno Limao, and Abigail Wozniak as well as seminar participants at the University of Maryland, Rotman School of Management, the Energy Institute at U.C. Berkeley, Georgetown, UC-Davis, UC-Irvine, and University of Michigan. We thank Danny Kim at NPD for answering our questions about the toy sales data and Kevin Mak at the Rotman Finance Lab for his assistance with assembling the stock price data. Molly Reckson provided capable research assistance. Financial support from the AIC Institute for Corporate Citizenship at the Rotman School of Management is gratefully acknowledged. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2009 by Seth M. Freedman, Melissa Schettini Kearney, and Mara Lederman. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Product Recalls, Imperfect Information, and Spillover Effects: ¸˛Lessons from the Consumer Response to the 2007 Toy Recalls Seth M. -

America's Most-Loved Toys and Games Deliver High Play Value This Holiday Season

America's Most-Loved Toys and Games Deliver High Play Value This Holiday Season Barbie(R), Hot Wheels(R), Polly Pocket(TM), Matchbox(R) and Fisher-Price(R) Among Brands That Top Kids' Wish Lists and Bring Festive Cheer to Families EL SEGUNDO, Calif., Nov 25, 2008 (BUSINESS WIRE) -- With just days until the kickoff of the holiday season and with finances top of mind, parents can look to the worldwide leader in toys and family products -- Mattel and Fisher-Price -- to find big "wow" presents as well as affordable gifts that will bring smiles to kids' faces. "Our long-standing kid-favorite Mattel and Fisher-Price brands offer a holiday toy line-up delivering the play value that parents want and the excitement and fun that kids need in order to keep their interest all year long. Our toys truly will create magical childhood memories and play experiences for kids of all ages and interests this holiday season," said Neil Friedman, president, Mattel Brands. For parents that are looking for that "wow gift" to surprise kids with this year, Mattel and Fisher-Price offer truly innovative items that will dazzle and amaze. From D-Rex(TM), a robotically recreated predator that walks, makes sounds and interacts with its owner and environment; to the three-foot tall Barbie(R) Three-Story Dream House(R), featuring a gourmet-style kitchen and working "escalator;" to Elmo LIVE!, a life-like, talking creation that tells stories, jokes, sings songs and plays games that are true to the Sesame Street puppet mannerisms, and the Power Wheels(R) A.T. -

Finding Aid to the Stefanie Eskander Papers, 1986-2018

Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play Stefanie Eskander Papers Finding Aid to the Stefanie Eskander Papers, 1986-2018 Summary Information Title: Stefanie Eskander papers Creator: Stefanie Eskander (primary) ID: 118.8603 Date: 1986-2018 (inclusive); 1990s (bulk) Extent: 7.5 linear feet (physical); 130 MB (digital) Language: This collection is in English. Abstract: The Stefanie Eskander papers are a compilation of concept sketches, presentation drawings, and other artwork for dolls, toys, and games created by Eskander for various toy companies. The bulk of the materials are from the 1990s. Repository: Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play at The Strong One Manhattan Square Rochester, New York 14607 585.263.2700 [email protected] Administrative Information Conditions Governing Use: This collection is open for research use by staff of The Strong and by users of its library and archives. Though the donor has not transferred intellectual property rights (including, but not limited to any copyright, trademark, and associated rights therein) to The Strong, she has given permission for The Strong to make copies in all media for museum, educational, and research purposes. Custodial History: The Stefanie Eskander papers were donated to The Strong in August 2018 as a gift of Stefanie Clark Eskander. The papers were accessioned by The Strong under Object ID 118.8603 and were received from Eskander in a portfolio and several oversized folders. Preferred citation for publication: Stefanie Eskander papers, Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play at The Strong Processed by: Julia Novakovic, January 2019 Controlled Access Terms Personal Names • Eskander, Stefanie Corporate Names • Hasbro, Inc. -

45936 MOC Must Toys Book6 12/1/05 7:52 Am Page 32

45936 MOC Must Toys Book6 12/1/05 7:52 am Page 32 1980s Consumer research was very much part of the production process in the US since the 1960s. In Britain, little consumer research had been done before the 1980s and little design input went into good advertising. In fact pre-war advertising as evidenced by the catalogues of Lines Bros. and Kiddicraft was far more eye catching. Combined with the difficulties thrown up by the current economic climate; increased imports, the rising cost of raw materials, increased labour costs and removal of fixed prices, it was inevitable that even large businesses could not guarantee long term security and survival. Desperate measures were tried by some, but by the beginning of the 1980s over sixteen British companies had collapsed including some of the major players; Lesney, Mettoy, Berwick Timpo and Airfix. Eventually these were to be absorbed by other companies in the US and the Far East, as well as in Britain. However, many major British companies managed to survive including some venerable examples, such as Britains, Spears, Hornby, Waddingtons, Galt and Cassidy Brothers. Torquil Norman started Bluebird Toys in 1983, his first product being the now famous Big Yellow Teapot House. This was one of the first ‘container’ houses which broke away from the traditional architectural style of dolls’ houses in favour of this light and colourful family home. He is also famous for his Big Red Fun Bus and Big Jumbo Fun 30 45936 MOC Must Toys Book6 12/1/05 7:52 am Page 33 Plane, Polly Pocket and the Then there were Mighty Max range, as fantasy toys which well as the invention took off in the of the plastic lunch 1980s with cute, box. -

Download Mastering the Universe: He-Man and the Rise and Fall of A

Mastering The Universe: He-man And The Rise And Fall Of A Billion-dollar Idea, Roger Sweet, David Wecker, Clerisy Press, 2005, 1578602238, 9781578602230, 224 pages. Mastering the Universe illuminates the creation, rise, and fall of one of the top-selling product lines in what is arguably the world's most competitive industry, toys -- and it does so from the perspective of Roger Sweet, the man who originated He-Man for Mattel. He-Man and the product line that grew out of it, Masters of the Universe (MOTU), created a fantasy world for boys that, at its height in 1986, reached $400 million in U.S. sales, only to plummet to $7 million the following year. During its six-year run, the MOTU line sold $1.2 billion worldwide and spawned a syndicated cartoon series and a major motion picture -- a feat not even the venerable Barbie can claim. Mastering the Universe explores the phenomenon of He-Man's popularity, as well as the shocking reasons behind the toy's rapid decline.. DOWNLOAD HERE Turning the Tides , Eugene Elander, Feb 18, 2011, Fiction, . The ancient Romans asked the question: "Who will watch the watchers?"In our own age as we face the scourge of global terrorism, we must also ask a further question: "Who will .... Possessed , , Dec 1, 1999, Comics & Graphic Novels, . Star Wars: Darth Maul , Ron Marz, Jan Duursema, Rick Magyar; Drew Struzan, , Comics & Graphic Novels, . In hiding for generations, the evil Sith have waited for the precise moment to reveal themselves and take vengeance upon the Jedi Order. -

Corporate Office Transfer Agent and Registrar Stockholder Administration Stock Exchange Listing Note Trustees Media Relations In

CORPORATE OFFICE ANNUAL MEETING 333 Continental Boulevard The Annual Meeting of Stockholders El Segundo, CA 90245-5012 will be held May 13, 2011, 9:00 a.m. at 310-252-2000 The Manhattan Beach Marriott 1400 Parkview Avenue For more information, please visit Mattel’s Manhattan Beach, CA 90266 corporate Web site: http://corporate.mattel.com FORM 10-K TRANSFER AGENT AND REGISTRAR Mattel’s Annual Report to the Securities and Mattel, Inc. Common Stock Exchange Commission on Form 10-K for the year Computershare Trust Company, N.A. ended December 31, 2010 is available on Mattel’s corporate Web site: http://corporate.mattel.com STOCKHOLDER ADMINISTRATION by calling toll-free 866-MAT-6973, or by writing to: Inquiries relating to stockholder accounting records, Secretary stock transfer and dividends (including dividend Mail Stop M1–1516 reinvestment) for Mattel, Inc. Common Stock Mattel, Inc. should be directed to: 333 Continental Boulevard Computershare Trust Company, N.A. El Segundo, CA 90245-5012 P.O. Box 43078 Providence, RI 02940-3078 TRADEMARK LEGENDS 888-909-9922 Apples to Apples®, BabyGear™, Barbie®, Barbie: A Fairy Secret™, Barbie: Web site: www.computershare.com/investor A Perfect Christmas™, Barbie Princess Charm School™, Battle Force 5®, Big Action™, Big Rig Buddies™, Blokus®, Fashionistas®, Fisher-Price®, Girl Tech®, Hero World™, Hot Wheels®, I can Be…®, Imaginext®, Ken®, Little STOCK EXCHANGE LISTING Mommy®, Little People®, Loopz®, Matchbox®, Max Steel®, Mindfl ex®, Monster High®, My Little Snuggabunny™, Nitro Racers™, Polly Pocket®, Mattel, Inc. Common Stock Power Wheels®, Radica®, Rev-Ups™, Rumblers®, See ‘N Say®, See The NASDAQ Stock Market Yourself™, Sing-a-ma-jigs™, Stealth Rides™, Trio®, Twirlin’ Whirlin Fun Ticker Symbol: MAT Park™, Tyco R/C®, UNO®, Video Racer™, View-Master®, Wall Tracks™ and Whac-a-Mole® trademarks and trade dress are owned by Mattel, Inc. -

Descarga Actionfan

EN ESTA ENTREGA: NÚMERO 3 - ENERO 2009 AF CLUB DE FIGURAS Revista On-line MUCHO DE HE- MAN: en informes separados recorreremos los comienzos de este clásico además de fantásticas figuras custom. LOS SUPERHÉROES DE MEGO: una marca que domino toda una década con sus geniales figuras de nuestros héroes preferidos que marcaron nuestra infancia. RAMBO Y LA FUERZA DE LA LIBERTAD: este héroe de acción que se transformo en figura y dibujo animado para divertirnos y llenarnos de coraje y fuerza. Y MÁSSSSSSSS COVER: ABEL GARCIA 01 CLUB DE FIGURAS NÚMERO 3 - ENERO 09` A EDITORIAL F Y acá estamos, una vez más, ya pasadas las fiestas y comenzamos el nuevo y esperado 2009, con las fuerzas renovadas y con muchas novedades para encarar este desafío que nos propusimos acercarles mes a mes para que puedan disfrutar junto a nosotros de este fascinante mundo de las figuras de acción. Realmente debo agradecer la gran aceptación que hemos tenido entre todos los conocedores y fans de las diferentes series y colecciones de figuras, quienes nos dan el incentivo y la motivación para llevarles la revista que muchos soñaron con poder leer y otros tantos colaboran para hacerla realidad. En este N°3, el primero del 2009, tenemos el gran gusto de contar con la participación del gran ilustrador español Abel García, quien nos sorprendió y emocionó con su gran cover de tapa inspirado en la temática de este número. También la inclusión de un nuevo colaborador, Sebastian Rizzo, quien en su presentación nos trae la colección de figuras de Rambo, nota ilustrada con fotografías de Ignacio (NachoToys). -

MATTEL, INC. 1998 ANNUAL REPORT Mattel, Inc

R2/COVERS TO PRINT 04/18/2000 11:11 AM Page 1 MATTEL, INC. 1998 ANNUAL REPORT Mattel, Inc. Mattel, Inc. 1998 Annual Report 333 Continental Boulevard El Segundo, California 90245 R2/COVERS TO PRINT 04/18/2000 11:11 AM Page 2 ©1999 Mattel, Inc. All Rights Reserved Printed in U.S.A. Printed on recycled paper. R4/1072MA 98AR.r7 2.0 04/18/2000 10:28 AM Page 5 Financial Highlights For the Year Operating Results (In millions) 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 Net Sales $3,971 $4,370 $4,535 $4,835 $4,782 Income (Before Restructuring, Extraordinary Item and Special Charges) 276 347 372 500 364 Net Income 225 338 372 285 332 As of Year End Financial Position (In millions) 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 Cash and Marketable Securities $ 290 $ 511 $ 550 $ 695 $ 212 Long-Term Debt 521 627 520 676 984 Total Stockholders’ Equity 1,386 1,552 1,806 1,822 1,820 R4/1072MA 98AR.r7 2.0 04/18/2000 12:06 PM Page 6 2 All Infant and Preschool brands and characters will now be marketed under the Fisher-Price name. To Our Shareholders: 1998 was a disappointing year for Mattel. Changes in our business, which we had anticipated would happen, occurred much more quickly and more dramatically than we ever expected. But we had initiatives well underway to address these changes, and we believe they will deliver positive, long-term results. So let’s review what happened and then tell you why we are so confident about our future.