DOCUMENT RESUME AUTHOR Pezzulich, Evelyn Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Psalm of Fear

A Psalm of Fear Psalm 31:1 To the choirmaster. A Psalm of David. For the end, a Psalm of David, an utterance of extreme fear. (LXX) In you, O LORD, do I take refuge; let me never be put to shame; in your righteousness deliver me! 2 Incline your ear to me; rescue me speedily! Be a rock of refuge for me, a strong fortress to save me! 3 For you are my rock and my fortress; and for your name's sake you lead me and guide me; 4 you take me out of the net they have hidden for me, for you are my refuge. 5 Into your hand I commit my spirit; you have redeemed me, O LORD, faithful God. 6 I hate those who pay regard to worthless idols, but I trust in the LORD. 7 I will rejoice and be glad in your steadfast love, because you have seen my affliction; you have known the distress of my soul, 8 and you have not delivered me into the hand of the enemy; you have set my feet in a broad place. 9 Be gracious to me, O LORD, for I am in distress; my eye is wasted from grief; my soul and my body also. 10 For my life is spent with sorrow, and my years with sighing; my strength fails because of my iniquity, and my bones waste away. 11 Because of all my adversaries I have become a reproach, especially to my neighbors, and an object of dread to my acquaintances; those who see me in the street flee from me. -

John Wesley's Manuscript Prayer Manual

John Wesley’s Manuscript Prayer Manual1 (c. 1730–1734) Editorial Introduction During his years as a student and active fellow at Oxford University, John Wesley filled a number of manuscript notebooks with material. Some were devoted to extracts from letters he had received, inventories of his personal library and expenses, and (after 1725) a diary. Others contained extended extracts from books he did not own, or collected short extracts from various sources on a topic (like his MS Poetry Miscellany). The survival of many of these notebooks is one of the rich resources for Wesley Studies. The largest portion that survive are part of the Colman Collection, now held in the Methodist Archives at The John Rylands Library in Manchester, England. Among these is a volume of prayers and psalms, mainly excerpted from published collections.2 A transcription of the contents of this notebook is provided below, identifying most of Wesley’s sources. (Those portions for which no source has been located are shown in blue font; they may be Wesley’s own creation, or from a yet unidentified source.) Before turning to the transcription it will be helpful to consider the context and purpose of the notebook. In the spiritual retrospective that he wove into his published Journal account of the transition he experienced on May 24, 1738, John Wesley emphasized that his earliest years at Epworth were in a home that adhered staunchly to the practice in the Church of England of morning and evening prayers, typically at the parish church. While he spoke of being ‘more -

Sexual Assault and Rape in Tahrir Square and Its Vicinity: a Compendium of Sources 2011 - 2013

Sexual Assault and Rape in Tahrir Square and its Vicinity: A Compendium of Sources 2011 - 2013 Prepared By: El-Nadeem Center for Rehabilitation of Victims of Violence and Torture - Nazra for Feminist Studies - New Woman Foundation February 2013 (2) Sexual Assault and Rape in Tahrir Square and its Vicinity: A Compendium of Sources FOREWORD .............................................................................................................................. 4 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 7 SEXUAL ASSAULT DURING THE FIRST ANNIVERSARY OF THE JANUARY 25 REVOLUTION ............................................................................................................................ 9 1. Testimony of Survivor - Basma ...................................................................................................... 9 SEXUAL ASSAULT ON JUNE 2012 ....................................................................................... 10 2. Testimony of Survivor – N ............................................................................................................. 10 3. Testimony of Survivor - C .............................................................................................................. 12 4. Testimony of Survivor - R .............................................................................................................. 15 5. Testimony of Sally Zohney ........................................................................................................... -

Flapping Genius! : the Ultimate Flappy Birds Trivia Challenge Pdf, Epub, Ebook

FLAPPING GENIUS! : THE ULTIMATE FLAPPY BIRDS TRIVIA CHALLENGE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK MR James Moore | 26 pages | 25 Nov 2014 | Createspace Independent Publishing Platform | 9781503332591 | English | none Flapping Genius! : The Ultimate Flappy Birds Trivia Challenge PDF Book Reasons to play this reactions-based arcade game: Nostalgic fans of 80s arcade games like Pong and Atari Breakout should appreciate the classic 80s gameplay with a fun twist for added excitement. Squareman 3. Newer Super Mario Bros. We suggest giving players lots of useful new games and lessons that you can draw from them. Higurashi no Naku Koro ni. If two player mode is activated, good teamwork is essential as you and your partner must work in tandem to defeat enemies! Click or hold down the screen to start shooting when you are an assassin and turn back when you are king. Not just in its sound but in his writing as well. Reasons to play this virtual bowling skill game: Whether you like to bowl in real life or just would like a taste of the indoor action, this cool and realistic version should whet your appetite to see some pins fall! Show off your sniping ability in this epic edition of the Sni[p]r series. Squareman 2. A steady hand, deft wrist and solid mouse control are also important for the smooth bowling action required to score strikes and spares at will. Metal Gear Solid: Peace Walker. MapleStory DS. Haunted Castle. Space Defenders. It is a scarce commodity, and requires a lot of skill to play well. Can you complete the training? Beat all the Robots and defend the earth! Nintendo 3DS Music. -

Read About Our Missions and Outreach Ministry on Page 4

Read about our Missions and Outreach Ministry on page 4. Empowering Disciples Magazine | Volume 07 from the BISHOP’S PEN By: Bishop Walter S. Thomas, Sr., Pastor The year 2016 is off to a great start. God has done so much for us and I am grateful. I pray that each of you have had a moment to reflect and plan how you want your year to go. Make sure you spend time with God and write the vision for this year. Plan to succeed and watch God bless your life. At New Psalmist we strive to make life better for someone else. The Missions and Outreach department does this on a consistent basis. They work tirelessly to ensure that others are taken care of and shown the love of Christ. I invite you to read about what they are doing and pray about where you can serve in this department. Before you know it, the snow will be gone, and spring will be here. As busy as life gets, remember to make time to attend church every week, and spend time with family and friends. God has done too much for you not to come and worship him. As a matter of fact bring your family and friends with you and worship God together. God Bless You. Bishop Walter S. Thomas Sr., Pastor 3 NewPsalmist.org from the EDITORBy: Joi Thomas What a wonderful year this has been so far. Bishop Thomas began the year with his series Light the Fire. I don’t know about you but that series showed me just what I need to do to get on the path God has ordained for me. -

The Light of Orthodoxy and the Darkness of Ecumenism1

Nineteenth Gathering for Orthodox Awareness Sunday of Orthodoxy February 20/March 4, 2012 The Light of Orthodoxy and the Darkness of Ecumenism1 † Bishop Klemes of Gardikion Secretary of the Holy Synod in Resistance Right Reverend Holy Hierarchs; Reverend Fathers and Mothers; Beloved brothers and sisters in Christ: I “There is no communion between light and darkness” ith the blessing of our ailing Metropolitan and Father Cyprian, Wand at the behest of our Standing Holy Synod, I enter with devout fear into the light of pristine Orthodoxy on the day of its splendid triumph over heresies. The Light of Orthodoxy is none other than the Light of Christ, which—as we exclaim at the Divine Liturgy of the Presanc- tified Gifts—“shineth upon all”! In the Hymns of Light (Φωταγωγικά) we seek Divine illumination from the Source of Light: “As Thou art the Light, O Christ, illumine me 1 A presentation on the occasion of the celebration of the Sunday of Orthodoxy, 2012, by the Holy Synod in Resistance at the Holy Convent of St. Paraskeve, Archarnai, Attica. The text here is published in its entirety, expanded and with footnotes. 1 in Thee, by the intercessions of the Theotokos, and save me.”2 “God is light, and in Him is no darkness at all.”3 This is Divine Light, true and uncreated, joyous Light, Grace and Truth, which came and manifested itself in Christ, in order to clothe us in the pri- mal raiment of incorruptibility. It is the Light of the Transfiguration, the Resurrection, and Pentecost, the eschatological Light of Life that knows no evening. -

Michigan Sugar, Area Bank a Popular Area Banquet Hall Union Optimistic~ Has Bcen Sold to Signaturc Bank of Bad Axe

-teamsgear up for season Pages S,6,7 i m n CAS SPRl N(;KxIT’ RTNnFRY VOLUME 92. NUMBER 23 --TY*. RONICLE - WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBERCHRONICLE 2,1998 FIFTY CENTS 14 PAGES SPRTNGPIW M N,W+ I Colony Contract vote near House sold Back to scho to Thumb Michigan Sugar, area bank A popular area banquet hall union optimistic~ has bcen sold to Signaturc Bank of Bad Axe. Michigan Sugar Company anything we could put in the employees and contracted crops. Signaturc Bank officials re- officials emerged from a con tract .” workers as it has since Aug. “We are committed to the ccntly confirmed the pur- marathon 12-hour bargain- Negotiators representing 7, when employees rejected 1,400 sugar beet growers who are the backbone of the chase of the Colony House, ing session Monday with Michigan Sugar and the the company’s settlement which was closed last year by some words of optimism, al- union spent more than 7 offer. agricultural community in long-time owners Marv and though no tentative agree- hours at the bargaining table The workers were subse- mid-Michigan. We will not Janice Winter. ment had been reached. Thursday after Don Power, a quently locked out of Michi- put their family farms and The facility, located miles Talks continued early this federal mediator, invited gan Sugar’s factories in Caro, livelihoods at risk.” 4 Negotiations began June 3 north of M-81 on M-53,for week as a lockout of some both sides to again try to Carrollton, Croswell and years hosted scores of trade 250 employees entered its work out their differences. -

A Manual of Plainsong for Divine Service Containing the Canticles

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. http://books.google.com MANUALOF PLAINSONG FOR DIVINE SERVICE CONTAINING THE CANTICLES NOTED THE PSALTER NOTED TO GREGORIAN TONES TOGETHER WITH THE LITANY AND RESPONSES A NEW EDITION PREPARED BY H. B. BRIGGS and W. H. FRERE UNDER THE GENERAL SUPERINTENDENCE OF JOHN STAINER (LATE PRESIDENT OF THE PLAINSONG AND MEDIAEVAL MUSIC SOCIETY) London : NOVELLO AND COMPANY, Limited AND NOVELLO, EWER AND CO., NEW YORK. 1902. rSt\5 LONDON I KOVELLO AND COMPANY, LIMITED PRINTERS. PREFACE. ThE first edition of The Psalter Noted was published in 1849 under the supervision of the late Rev. Thomas Helmore, and secured for the Gregorian Tones a general recognition of their appropriateness for Divine worship. Subsequently Mr. Helmore's scheme was enlarged by the issue of The Canticles Noted, of A Brief Directory, and of three Appendixes to the Psalter; and the whole collection was issued in one volume under the title of A Manual of Plainsong. The Manual had also two companion books, one of Words only containing The Canticles and Psalter Accented, the other a collection of Accompanying Harmonies. Thus complete provision was made for the musical performance of the regular services of the Prayer Book. Practical objections, however, to the monotony of the recitation of several Psalms to one Tone without the relief of Antiphons, added to certain difficulties in the pointing, led to the issue of other Psalters which have competed with The Psalter Noted, but without obtaining, any of them, a marked supremacy ; and nothing has been issued which covers the whole field so completely as Mr. -

Episode Guide

Episode Guide Episodes 001–045 Last episode aired Thursday August 31, 2017 www.nbc.com c c 2017 www.tv.com c 2017 www.nbc.com c 2017 gossipandgab.com c 2017 celebdirtylaundry.com The summaries and recaps of all the The Night Shift episodes were downloaded from http://www.tv.com and http: //www.nbc.com and http://gossipandgab.com and http://celebdirtylaundry.com and processed through a perl program to transform them in a LATEX file, for pretty printing. So, do not blame me for errors in the text ^¨ This booklet was LATEXed on September 2, 2017 by footstep11 with create_eps_guide v0.59 Contents Season 1 1 1 Pilot ...............................................3 2 Second Chances . .7 3 HogWild.............................................9 4 Grace Under Fire . 11 5 Storm Watch . 13 6 Coming Home . 15 7 Blood Brothers (1) . 17 8 Save Me (2) . 19 Season 2 21 1 Recovery . 23 2 Back at the Ranch . 27 3 Eyes Look Your Last . 29 4 Shock to the Heart . 31 5 Ghosts . 33 6 FogofWar............................................ 35 7 Need to Know . 37 8 Best Laid Plans . 39 9 Parenthood . 41 10 Aftermath . 43 11 Hold On . 45 12 Moving On . 47 13 Sunrise, Sunset . 49 14 Darkest Before Dawn . 53 Season 3 57 1 The Times They Are A-Changin’ (1) . 59 2 The Thing With Feathers (2) . 61 3 The Way Back . 63 4 Three-Two-One . 65 5 Get Busy Livin’ . 67 6 Hot in the City . 69 7 By Dawn’s Early Light . 71 8 AllIn............................................... 73 9 Unexpected . 75 10 Between a Rock and a Hard Place . -

'3 Is the Magic Number'

‘The Alignment of the Signs.’ By John Carothers 1 CHAPTER ONE 'Oi look there's a chav That means council housed and violent He's got a hoodie on give him a hug On second thoughts don't you don't wanna get mugged Oh shit too late that was kinda dumb Whose idea was that stupid He's got some front, ain't we all Be the joker, play the fool What's politics, ain't it all Smoke and mirrors, April fools All year round, all in all Just another brick in the wall Get away with murder in the schools Use four letter swear words coz we're cool We've had it with you politicians you bloody rich kids never listen There's no such thing as broken Britain We're just bloody broke in Britain What needs fixing is the system Not shop windows down in Brixton Riots on the television You can't put us all in prison Oi! I said Oi What you looking at you little rich boy.' Ill Manners – Plan B. 2 'Shatter Class' The following cause can be adopted by the Jewish, Christian and Islamic faiths as they all refer to the book of Genesis. But first: 1) 'Again I tell you, it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God.' ( Matthew 19:24 ) I grew up in Lytham St Annes. It was mostly a middle or upper class community. They were rich and insured whereas I lived in a council house. -

Client List August 2021

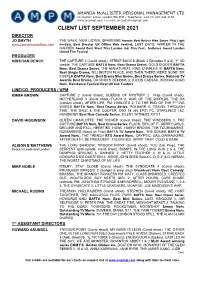

AMANDA McALLISTER PERSONAL MANAGEMENT LTD 74 Claxton Grove, London W6 8HE • Telephone: +44 (0) 207 244 1159 www.ampmgt.com • e-mail: [email protected] CLIENT LIST SEPTEMBER 2021 DIRECTOR JO SMYTH THE WALK, MUM LISTEN, SPAREBNB Awards Best British Web Series Pilot Light www.captainhowdyfilms.com Festival, Best Director UK Offline Web Festival, LAST DAYS, WINTER IN THE GARDEN Award Best Short Film London Ind. Film Fest., Audience Award London United Film Festival PRODUCER KRISTIAN DENCH THE CAPTURE 2 (Covid shoot), STRIKE BACK 8 (Block 3 Episodes 5 & 6), 1st AD credits: THE CAPTURE BAFTA Nom. Best Drama Series, GOLD DIGGER BAFTA Nom. Best Drama Series, THE MINIATURIST, KING CHARLES III, BAFTA Nom. Best Single Drama, RILLINGTON PLACE, AND THEN THERE WERE NONE, DR FOSTER BAFTA Nom. Best Drama Mini Series, Best Drama Series, National TV Awards Best Drama, DA VINCI’S DEMONS 3, JULIUS CAESAR, WICKAM ROAD Nom. Raindance Festival Best UK Ind. Feature LINE/CO. PRODUCERS / UPM EMMA BROWN CAPTURE 2 (Covid shoot), QUEENS OF MYSTERY 2 Prep (Covid shoot), MOTHERLAND 3 (Covid shoot) FLACK 2, WAR OF THE WORLDS, THE OA (London shoot), AFTER LIFE, PM: HARLOTS 2, TO THE END OF THE F***ING WORLD BAFTA Nom. Best Drama Series, POLDARK III, TRAVEL THROUGH TIME, THE DALE & THE COOPER, DIXI 14 (40 EPS) PC: STARLINGS 1&2, HUNDERBY Best New Comedy Series, SILENT WITNESS XV111 DAVID HIGGINSON QUEEN CHARLOTTE, THE POWER (Covid shoot), THE WINDSORS 3, THE CAPTURE BAFTA Nom. Best Drama Series, FLACK, SICK OF IT, DERRY GIRLS, DECLINE AND FALL, HERETIKS, HOWL, HARRY BROWN, THE TOURNAMENT, NUREMBERG (Nazis on Trial) BAFTA TV Award Nom., THE SOMME BAFTA TV Award Nom., THE TRENCH RTS Award Nom., CRYPTIC, GALLOWWALKERS, AFTER DEATH, DE PRESIDENT, TALION (3D), SPIRIT TRAP, COLD & DARK ALISON B MATTHEWS THE LONG SHADOW, TRIGGER POINT (Covid shoot), YOU (UK Prep), THE Bases in Leeds and London SERPENT (pick-up/add. -

Charente-Maritime Sud Ouest & Vous

Chepniers Un motard tué, sa passagère grièvement LUNDI 27 JUIN 2016 - 1,10$ www.sudouest.fr blessée Page 14 SAINTES/ROYAN/JONZACSAINTES/ROYAN/JONZAC Fête du cinéma Un réseau unique de salles obscures Des multiplexes mais aussi des salles rurales, des cinémas d’art et essai... e La France, pays de 7 art. Pages 2-3 Commerce viticole Les Anglais seront toujours clients Page 11 Brexit : la diplomatie sur la brèche Antoine Griezmann, auteur d’un doublé – 58e et 61e minute – congratulé par ses coéquipiers. PHOTO J.-P. KSIAZEK/AFP UNION EUROPÉENNE Les chefs d’États européens auront fort à faire cette semaine pour préparer le départ britannique. Ces France et Allemagne sont Bleus en première ligne. Page 6 ont du caractère EURO 2016 Menés au score dès le début du match, les Français ont su renverser la vapeur et venir à bout d’une défense Manuel Valls et François Hollande recevaient hier le Premier ministre italien Matteo Renzi pour R 20319 23170 1.10$ $:HIMKNB=^UVVUV:?C@D@L@H@K irlandaise opiniâtre (2-1). Rendez-vous dimanche en quart. Sp. p. 2 à 8 évoquer les conséquences du Brexit. PHOTO C. SAIDI/AFP 2 Lundi 27 juin 2016 SUD OUEST Le fait du jour Le septième art près de chez vous FÊTE DU CINÉMA Face aux grands groupes et aux multiplexes, les salles de proximité résistent mieux qu’on ne le pense. Gros plan sur le succès du Zoetrope, à Blaye (33) JULIEN ROUSSET temps », explique Youen Bernard, di- 32E FÊTE DU CINÉMA [email protected] recteur du Zoetrope.