Angola Country Profile Update 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Angolan Giraffe (Giraffa Camelopardalis Ssp

Angolan Giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis ssp. angolensis) Appendix 1: Historical and recent geographic range and population of Angolan Giraffe G. c. angolensis Geographic Range ANGOLA Historical range in Angola Giraffe formerly occurred in the mopane and acacia savannas of southern Angola (East 1999). According to Crawford-Cabral and Verissimo (2005), the historic distribution of the species presented a discontinuous range with two, reputedly separated, populations. The western-most population extended from the upper course of the Curoca River through Otchinjau to the banks of the Kunene (synonymous Cunene) River, and through Cuamato and the Mupa area further north (Crawford-Cabral and Verissimo 2005, Dagg 1962). The intention of protecting this western population of G. c. angolensis, led to the proclamation of Mupa National Park (Crawford-Cabral and Verissimo 2005, P. Vaz Pinto pers. comm.). The eastern population occurred between the Cuito and Cuando Rivers, with larger numbers of records from the southeast corner of the former Mucusso Game Reserve (Crawford-Cabral and Verissimo 2005, Dagg 1962). By the late 1990s Giraffe were assumed to be extinct in Angola (East 1999). According to Kuedikuenda and Xavier (2009), a small population of Angolan Giraffe may still occur in Mupa National Park; however, no census data exist to substantiate this claim. As the Park was ravaged by poachers and refugees, it was generally accepted that Giraffe were locally extinct until recent re-introductions into southern Angola from Namibia (Kissama Foundation 2015, East 1999, P. Vaz Pinto pers. comm.). BOTSWANA Current range in Botswana Recent genetic analyses have revealed that the population of Giraffe in the Central Kalahari and Khutse Game Reserves in central Botswana is from the subspecies G. -

Country Profile Republic of Zambia Giraffe Conservation Status Report

Country Profile Republic of Zambia Giraffe Conservation Status Report Sub-region: Southern Africa General statistics Size of country: 752,614 km² Size of protected areas / percentage protected area coverage: 30% (Sub)species Thornicroft’s giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis thornicrofti) Angolan giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis angolensis) – possible South African giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis giraffa) – possible Conservation Status IUCN Red List (IUCN 2012): Giraffa camelopardalis (as a species) – least concern G. c. thornicrofti – not assessed G. c. angolensis – not assessed G. c. giraffa – not assessed In the Republic of Zambia: The Zambia Wildlife Authority (ZAWA) is mandated under the Zambia Wildlife Act No. 12 of 1998 to manage and conserve Zambia’s wildlife and under this same act, the hunting of giraffe in Zambia is illegal (ZAWA 2015). Zambia has the second largest proportion of land under protected status in Southern Africa with approximately 225,000 km2 designated as protected areas. This equates to approximately 30% of the total land cover and of this, approximately 8% as National Parks (NPs) and 22% as Game Management Areas (GMA). The remaining protected land consists of bird sanctuaries, game ranches, forest and botanical reserves, and national heritage sites (Mwanza 2006). The Kavango Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA TFCA), is potentially the world’s largest conservation area, spanning five southern African countries; Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe, centred around the Caprivi-Chobe-Victoria Falls area (KAZA 2015). Parks within Zambia that fall under KAZA are: Liuwa Plain, Kafue, Mosi-oa-Tunya and Sioma Ngwezi (Peace Parks Foundation 2013). GCF is dedicated to securing a future for all giraffe populations and (sub)species in the wild. -

Final Report: Southern Africa Regional Environmental Program

SOUTHERN AFRICA REGIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL PROGRAM FINAL REPORT DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. FINAL REPORT SOUTHERN AFRICA REGIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL PROGRAM Contract No. 674-C-00-10-00030-00 Cover illustration and all one-page illustrations: Credit: Fernando Hugo Fernandes DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. CONTENTS Acronyms ................................................................................................................ ii Executive Summary ............................................................................................... 1 Project Context ...................................................................................................... 4 Strategic Approach and Program Management .............................................. 10 Strategic Thrust of the Program ...............................................................................................10 Project Implementation and Key Partners .............................................................................12 Major Program Elements: SAREP Highlights and Achievements .................. 14 Summary of Key Technical Results and Achievements .......................................................14 Improving the Cooperative Management of the River -

Inventário Florestal Nacional, Guia De Campo Para Recolha De Dados

Monitorização e Avaliação de Recursos Florestais Nacionais de Angola Inventário Florestal Nacional Guia de campo para recolha de dados . NFMA Working Paper No 41/P– Rome, Luanda 2009 Monitorização e Avaliação de Recursos Florestais Nacionais As florestas são essenciais para o bem-estar da humanidade. Constitui as fundações para a vida sobre a terra através de funções ecológicas, a regulação do clima e recursos hídricos e servem como habitat para plantas e animais. As florestas também fornecem uma vasta gama de bens essenciais, tais como madeira, comida, forragem, medicamentos e também, oportunidades para lazer, renovação espiritual e outros serviços. Hoje em dia, as florestas sofrem pressões devido ao aumento de procura de produtos e serviços com base na terra, o que resulta frequentemente na degradação ou transformação da floresta em formas insustentáveis de utilização da terra. Quando as florestas são perdidas ou severamente degradadas. A sua capacidade de funcionar como reguladores do ambiente também se perde. O resultado é o aumento de perigo de inundações e erosão, a redução na fertilidade do solo e o desaparecimento de plantas e animais. Como resultado, o fornecimento sustentável de bens e serviços das florestas é posto em perigo. Como resposta do aumento de procura de informações fiáveis sobre os recursos de florestas e árvores tanto ao nível nacional como Internacional l, a FAO iniciou uma actividade para dar apoio à monitorização e avaliação de recursos florestais nationais (MANF). O apoio à MANF inclui uma abordagem harmonizada da MANF, a gestão de informação, sistemas de notificação de dados e o apoio à análise do impacto das políticas no processo nacional de tomada de decisão. -

Overview of the Cubango Okavango

Transboundary Cooperation for Protecting the Cubango- Okavango River Basin and Improving the Integrity of the Okavango Delta World Heritage Property Overview of the Cubango-Okavango River Basin in Angola: Challenges and Perspectives Maun, 3-4 June 2019 Botswana National Development Plan (2018-2022) The National Development Plan 6 Axis provides framework for the development of infrastructure, 25 Policies environmental sustainability and land and territorial planning. 83 Programs Cubango-Okavango River Basin Key Challenges To develop better conditions for the economic development of the region. To foster sustainable development considering technical, socio- economic and environmental aspects. To combat poverty and increase the opportunities of equitable socioeconomic benefits. Key Considerations 1. Inventory of the water needs and uses. 2. Assessment of the water balance between needs and availability. 3. Water quality. 4. Risk management and valorization of the water resources. Some of the Main Needs Water Institutional Monitoring Capacity Network Decision- Participatory making Management Supporting Systems Adequate Funding Master Plans for Cubango Zambezi and Basins Cubango/ Approved in 6 main Up to 2030 Okavango 2016 programs Final Draft 9 main Zambezi Up to 2035 2018 programs Cubango/Okavango Basin Master Plan Main Programs Rehabilitation of degraded areas. Maintaining the natural connectivity between rivers and river corridors. Implementing water monitoring network. Managing the fishery activity and water use. Biodiversity conservation. Capacity building and governance. Zambezi Basin Master Plan Main Programs Water supply for communities and economic activities. Sewage and water pollution control. Economic and social valorisation of water resources. Protection of ecosystems. Risk management. Economic sustainability of the water resources. Institutional and legal framework. -

Chapter 15 the Mammals of Angola

Chapter 15 The Mammals of Angola Pedro Beja, Pedro Vaz Pinto, Luís Veríssimo, Elena Bersacola, Ezequiel Fabiano, Jorge M. Palmeirim, Ara Monadjem, Pedro Monterroso, Magdalena S. Svensson, and Peter John Taylor Abstract Scientific investigations on the mammals of Angola started over 150 years ago, but information remains scarce and scattered, with only one recent published account. Here we provide a synthesis of the mammals of Angola based on a thorough survey of primary and grey literature, as well as recent unpublished records. We present a short history of mammal research, and provide brief information on each species known to occur in the country. Particular attention is given to endemic and near endemic species. We also provide a zoogeographic outline and information on the conservation of Angolan mammals. We found confirmed records for 291 native species, most of which from the orders Rodentia (85), Chiroptera (73), Carnivora (39), and Cetartiodactyla (33). There is a large number of endemic and near endemic species, most of which are rodents or bats. The large diversity of species is favoured by the wide P. Beja (*) CIBIO-InBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Universidade do Porto, Vairão, Portugal CEABN-InBio, Centro de Ecologia Aplicada “Professor Baeta Neves”, Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal e-mail: [email protected] P. Vaz Pinto Fundação Kissama, Luanda, Angola CIBIO-InBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Universidade do Porto, Campus de Vairão, Vairão, Portugal e-mail: [email protected] L. Veríssimo Fundação Kissama, Luanda, Angola e-mail: [email protected] E. -

Mensagem Sobre O Estado Da Nação, De Sua Excelência João Lourenço, Presidente Da República De Angola Luanda, 15 De Outubro

1 Mensagem sobre o Estado da Nação, de Sua Excelência João Lourenço, Presidente da República de Angola Luanda, 15 de Outubro de 2019 -Sua Excelência Fernando da Piedade Dias dos Santos, Presidente da Assembleia Nacional, -Sua Excelência Bornito de Sousa, Vice-Presidente da República, -Excelentíssimos Senhores Deputados, -Venerandos Juízes Presidentes dos Tribunais Constitucional e Supremo, -Prezados Membros do Executivo, -Distintos Membros do Corpo Diplomático, -Ilustres Convidados, -Caros Compatriotas, Permitam-me a partir desta tribuna dirigir uma especial saudação a todo o povo angolano e aos dignos Deputados que o representam nesta Casa da Democracia. Cumpriram-se no passado mês de Setembro dois anos do mandato que me foi conferido nas urnas, e embora tenha empenhado o melhor dos meus esforços na aplicação do programa de governação que mereceu a confiança da maioria dos eleitores, estou consciente de que muito ainda há por realizar para satisfação das grandes necessidades que o povo enfrenta. 1 2 O nosso foco continua a ser a boa governação, a defesa do rigor e da transparência em todos os actos públicos, a luta contra a corrupção e a impunidade, a reanimação e diversificação da economia, o resgate dos valores da cidadania e a moralização da sociedade no seu todo, bases indispensáveis para se garantir o progresso social e o desenvolvimento sustentável do país. Na nossa acção governativa consideramos fundamental a instauração em Angola de um verdadeiro Estado Democrático de Direito e a construção de uma economia de mercado que seja capaz de diversificar efectivamente a economia nacional e alterar em termos definitivos a estrutura económica de Angola, hoje muito dependente do sector público e das receitas da exportação do petróleo bruto. -

Mavinga Management Plan Rev 8 July 2016.Pdf

Management Plan Mavinga National Park, Kuando Kubango, Angola for the period: 2016-2020 ! ! !! ! ! Southern Africa Regional Environment Programme !"#$%& !"##$%&'()*&+,*-"-&.'(./0,*1.(.),1,(&*$2*&+,*34.5.()$*6'5,%*7.-'(* ! Control page Project: Report: Management Plan for the Mavinga Project code: USAID PRIME National Park, Kuando Kubango, Angola CONTRACT NO. 674-C-00-10-00030-00 Versions: First Draft Report - 28 April 2016 Second Draft Report – 8 July 2016 Compiled by: Name: Peter Tarr Organisation: Southern African Institute for Environmental Assessment Position: Executive Director Signature: Date: 8 July 2016 Distribution Information Client Copies Date SAREP 1 soft copy 2016 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents ..................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Acronyms ................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................................... -

Proposal for Inclusion of the Giraffe

CMS Distribution: General CONVENTION ON MIGRATORY UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.1.10 25 May 2017 SPECIES Original: English 12th MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Manila, Philippines, 23 - 28 October 2017 Agenda Item 25.1 PROPOSAL FOR THE INCLUSION OF THE GIRAFFE (Giraffa camelopardalis) ON APPENDIX II OF THE CONVENTION Summary: The Government of Angola has submitted the attached proposal* for the inclusion of the Giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis) on Appendix II of CMS. *The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CMS Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.1.10 PROPOSAL FOR THE INCLUSION OF THE GIRAFFE (Giraffa camelopardalis) ON APPENDIX II OF THE CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF MIGRATORY SPECIES OF WILD ANIMALS A. PROPOSAL: Inclusion of Giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis) on Appendix II - Migratory species requiring international cooperation B. PROPONENT: Government of Angola C. SUPPORTING STATEMENT: 1.Taxon 1.1 Classis: Mammalia 1.2 Order: Artiodactyla 1.3 Family: Giraffidae 1.4 Genus/Species/subspecies: Giraffa camelopardalis (Linnaeus, 1758) 1.5 Scientific synonyms: 1.6 Common name(s): Giraffe 2. Overview Among the large mammals of Africa, giraffe are among the least studied, yet are increasingly under threat. Recently, the giraffe species was uplisted to Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List, having declined by an estimated 40% in the last 30 years, further highlighting the increasing need to protect them. -

Africa's Giraffe

AFRICA’S GIRAFFE A CONSERVATION GUIDE CONTENTS Introduction 1 Evolution 2 Giraffe & humans 2 Giraffe facts 3 Taxonomy & species 5 Distribution & habitat 7 Masai giraffe 9 Northern giraffe 10 Kordofan giraffe 10 Nubian giraffe 11 West African giraffe 12 Reticulated giraffe 13 Southern giraffe 14 Angolan giraffe 14 South African giraffe 15 Conservation 17 Status & statistics 17 IUCN Red List 17 Species & numbers 18 CITES & CMS 20 Stakeholders 20 Threats 21 Limiting factors 22 Significance of giraffe 24 Economic 24 Ecological 24 The future 25 Giraffe Conservation Foundation 26 Bibliography 27 BILLY DODSON In order to address this, the Giraffe Conservation Foundation (GCF) has drafted an Africa-wide Giraffe Strategic Framework, which provides a road-map for giraffe conservation throughout Africa, and supports several governments in developing their first National Giraffe Conservation Strategies and Action Plans. Now is the time to act for giraffe, before time runs out. Evolution Helladotherium, a three-metre-tall antelope-like animal, which once WIKIMEDIA COMMONS roamed the plains and forests of Asia and Europe between the Eocene and Oligocene epochs 30-50 million years ago, is the forefather of the two remaining members of the Giraffidae family: the giraffe we know today, and the okapi. To date, more than ten fossil genera have been discovered, revealing that by the Miocene epoch, 6-20 million years ago, early deer-like These giraffe images, which are carved life-size and with incredible detail into rock, are believed giraffids were yet to develop the characteristic long neck of today’s giraffe. to date back 9,000 years to a time when the Sahara was wet and green. -

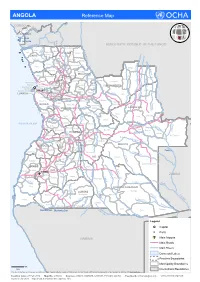

ANGOLA Reference Map

ANGOLA Reference Map CONGO L Belize ua ng Buco Zau o CABINDA Landana Lac Nieba u l Lac Vundu i Cabinda w Congo K DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO o z Maquela do Zombo o p Noqui e Kuimba C Soyo M Mbanza UÍGE Kimbele u -Kongo a n ZAIRE e Damba g g o id Tomboco br Buengas M Milunga I n Songo k a Bembe i C p Mucaba s Sanza Pombo a i a u L Nzeto c u a i L l Chitato b Uige Bungo e h o e d C m Ambuila g e Puri Massango b Negage o MALANGE L Ambriz Kangola o u Nambuangongo b a n Kambulo Kitexe C Ambaca m Marimba g a Kuilo Lukapa h u Kuango i Kalandula C Dande Bolongongo Kaungula e u Sambizanga Dembos Kiculungo Kunda- m Maianga Rangel b Cacuaco Bula-Atumba Banga Kahombo ia-Baze LUNDA NORTE e Kilamba Kiaxi o o Cazenga eng Samba d Ingombota B Ngonguembo Kiuaba n Pango- -Caju a Saurimo Barra Do Cuanza LuanCda u u Golungo-Alto -Nzoji Viana a Kela L Samba Aluquem Lukala Lul o LUANDA nz o Lubalo a Kazengo Kakuso m i Kambambe Malanje h Icolo e Bengo Mukari c a KWANZA-NORTE Xa-Muteba u Kissama Kangandala L Kapenda- L Libolo u BENGO Mussende Kamulemba e L m onga Kambundi- ando b KWANZA-SUL Lu Katembo LUNDA SUL e Kilenda Lukembo Porto Amboim C Kakolo u Amboim Kibala t Mukonda Cu a Dala Luau v t o o Ebo Kirima Konda Ca s Z ATLANTIC OCEAN Waco Kungo Andulo ai Nharea Kamanongue C a Seles hif m um b Sumbe Bailundo Mungo ag e Leua a z Kassongue Kuemba Kameia i C u HUAMBO Kunhinga Luena vo Luakano Lobito Bocoio Londuimbali Katabola Alto Zambeze Moxico Balombo Kachiungo Lun bela gue-B Catum Ekunha Chinguar Kuito Kamakupa ungo a Benguela Chinjenje z Huambo n MOXICO -

Trip Report: Aquatic Biodiversity Survey of the Lower Cuito and Cuando River Systems in Angola

Trip Report: Aquatic biodiversity survey of the lower Cuito and Cuando river systems in Angola. April 2013 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. Table of Contents Introduction 3 Methods 5 Survey Timing 5 Survey Sites 5 Sampled Taxa 8 Results 9 Fish 9 Herpetofauna 15 Crocodiles (Crocodylus niloticus) 20 Botanical Report 25 Birds 35 Dragonflies and Damselflies 36 General observations 37 Observed threats to biodiversity 38 Way forward 39 i Southern African Regional Environmental Programme Executive Summary The Southern Africa Regional Environmental Program (SAREP) has a strategic goal to improve the conservation and sustainable use of biological resources of the Cubango- Okavango River Basin. This report fulfils one of the initial steps in helping to mitigate a critical threat to biodiversity within the system, i.e.; Poor Knowledge of the Status, Extent and Factors Regulating Biodiversity within the Basin (Indirect Threat) (SAREP, 2012), providing information on some of the aquatic faunal diversity of the Cubango-Okavango basin within Angola. This report provides a summary of the initial findings of the survey as well as general field conditions and observations. This survey is the second of its kind organised by the Southern African Regional Environmental Programme (SAREP) and the first survey took place in May 2012. The results of this initial survey were documented by Brooks (2012). The surveys are a collaborative venture between SAREP and the Angolan Ministry of Environment‟s (MINAMB) Institute of Biodiversity and the Angolan Ministry of Agricultures National Institute of Fish Research (INIP).