Iran's Nuclear Program: Tehran's Compliance with International

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

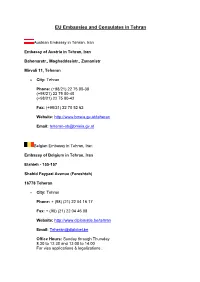

EU Embassies and Consulates in Tehran

EU Embassies and Consulates in Tehran Austrian Embassy in Tehran, Iran Embassy of Austria in Tehran, Iran Bahonarstr., Moghaddasistr., Zamanistr Mirvali 11, Teheran City: Tehran Phone: (+98/21) 22 75 00-38 (+98/21) 22 75 00-40 (+98/21) 22 75 00-42 Fax: (+98/21) 22 70 52 62 Website: http://www.bmeia.gv.at/teheran Email: [email protected] Belgian Embassy in Tehran, Iran Embassy of Belgium in Tehran, Iran Elahieh - 155-157 Shahid Fayyazi Avenue (Fereshteh) 16778 Teheran City: Tehran Phone: + (98) (21) 22 04 16 17 Fax: + (98) (21) 22 04 46 08 Website: http://www.diplomatie.be/tehran Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Sunday through Thursday 8.30 to 12.30 and 13.00 to 14.00 For visa applications & legalizations : Sunday through Tuesday from 8.30 to 11.30 AM Bulgarian Embassy in Tehran, Iran Bulgarian Embassy in Tehran, Iran IR Iran, Tehran, 'Vali-e Asr' Ave. 'Tavanir' Str., 'Nezami-ye Ganjavi' Str. No. 16-18 City: Tehran Phone: (009821) 8877-5662 (009821) 8877-5037 Fax: (009821) 8877-9680 Email: [email protected] Croatian Embassy in Tehran, Iran Embassy of the Republic of Croatia in Tehran, Iran 1. Behestan 25 Avia Pasdaran Tehran, Islamic Republic of Iran City: Tehran Phone: 0098 21 258 9923 0098 21 258 7039 Fax: 0098 21 254 9199 Email: [email protected] Details: Covers the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Details: Ambassador: William Carbó Ricardo Cypriot Embassy in Tehran, Iran Embassy of the Republic of Cyprus in Tehran, Iran 328, Shahid Karimi (ex. -

Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization

Statement to the 63rd regular session of the General Conference of the International Atomic Energy Agency Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization 19 September 2019 Madam President, Excellencies, Distinguished delegates, Ladies and Gentlemen, Allow me to express my congratulations on your election, Madam President, and to wish you, the IAEA Member States and the Secretariat, a productive conference. I am pleased to deliver this statement on behalf of the Executive Secretary of the Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban-Treaty Organization. At the outset, I would like to join others in conveying our deepest sympathy to the International Atomic Energy Agency for the passing of its Director General, Yukiya Amano. While this is a great loss for the international community, we know that Mr Amano’s legacy as an exemplary diplomat and respected leader will remain. It was largely during his term that the IAEA and CTBTO came to work more closely together, addressing some of the pressing issues facing the international community. Indeed, while the mandates of the two organizations are distinct, the CTBTO Preparatory Commission and the International Atomic Energy Agency have always had much in common: we both work towards the creation of a safe and secure world, free of the threat of nuclear weapons. We both contribute to the global nuclear non-proliferation and disarmament regime. The principles and methods that underpin our work also bring us together. Multilateralism, verification and cooperation have formed the basis for many of the Agency’s accomplishments. Both our organizations enjoy large memberships and rely on science and technology to serve and support our Member States. -

New Climatic Zones in Iran: a Comparative Study of Different Empirical Methods and Clustering Technique

New Climatic Zones in Iran: A Comparative Study of Different Empirical Methods and Clustering Technique Faezeh Abbasi University of Tehran Saeed Bazgeer ( [email protected] ) University of Tehran https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7044-0528 Parviz Rezazadeh Kalehbasti I.R. of Iran Meteorological Organization (IRIMO) Ebrahim Asadi Oskoue Atmospheric Science and Meteorological Research Center Masoud Haghighat I.R. of Iran Meteorological Organization (IRIMO) Pouya Rezazadeh Kalebasti Stanford University, Research Article Keywords: Climatic classication, Climatic zones, Cluster analysis, Precipitation gradient, Thornthwaite and Mather method Posted Date: June 2nd, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-570400/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License 1 Faezeh Abbasi1, Saeed Bazgeer2*, Parviz Rezazadeh Kalehbasti3, Ebrahim Asadi Oskoue4, 2 Masoud Haghighat5, Pouya Rezazadeh Kalebasti6 3 4 5 New Climatic Zones in Iran: A Comparative Study of Different Empirical Methods and 6 Clustering Technique 7 8 1Faezeh Abbasi, Ph.D., Agricultural Climatology, Department of Physical Geography, Faculty 9 of Geography, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran 10 e-mail address: [email protected] 11 12 2*Saeed Bazgeer, Corresponding author, Assistant Professor, Department of Physical 13 Geography, Faculty of Geography, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran 14 e-mail address: [email protected] 15 Orcid Id: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7044-0528 16 17 3Parviz Rezazadeh Kalehbasti, Synoptic Meteorologist, I.R. of Iran Meteorological 18 Organization (IRIMO), Tehran, Iran 19 e-mail address: [email protected] 20 21 4Ebrahim Asadi Oskoue, Assistant Professor, Department of Agricultural Meteorology, 22 Atmospheric Science and Meteorological Research Center, Tehran, Iran 23 e-mail address: [email protected] 24 25 5Masoud Haghighat, Agricultural Meteorologist, I.R. -

International Workshop on “Adaptation to Water Scarcity and Basin-Connected Cities”

Call for Papers/ Country Reports International workshop on “Adaptation to Water Scarcity and Basin-connected Cities” 10-12 December 2018, Mashhad-Iran On the occasion of the 8th Asian G-WADI and 2nd IDI Meetings Background Water scarcity is the lack of sufficient available water resources to meet demands of water usage within a region. This condition arises as consequence of a high rate of accumulated demand from all water-using sectors including agriculture, domestic, industry and environment compared with available supply, under the prevailing institutional arrangements and infrastructural conditions. The international workshop on “Adaptation to Water Scarcity and Basin- Connected Cities” is designed to bring together researchers and practitioners alike including governmental officials, private and public sectors, water managers, urban planners as well as decision and policy makers engaged in various aspects of water scarcity adaptation and the new concept basin- connected cities. The workshop provide contribution the implementation of the Eighth Phase of IHP (2014- 2021) “Water Security: Addressing Local, Regional and Global Challenges” and in particular, within the activities of the two-flagship prorgamme of IHP IDI and G-WADI. This international workshop provides a unique opportunity for various specialists to exchange ideas and experiences. International Organizers The workshop will be held on the occasion of the 8th Asian G-WADI and 2nd International Drought Initiative (IDI) meetings in Mashhad, Iran, 10-12 December 2018, organized -

Climatic and Thermal Comfort Research Orientations in Outdoor Spaces: from 1999 to 2017 in Iran

International Journal of Architecture and Urban Development E-ISSN 2345-2331 © 2019 IAU Archive of Vol. SID 9, No.4. P 45-60. Autumn 2019 Development Urban and Of Architecture Journal International Climatic and thermal comfort research orientations in outdoor spaces: From 1999 to 2017 in Iran 1*Bahareh Bannazadeh, 2Shahin Heidari., 3Ali Jazaeri 1*PhD Candidate, University of Tehran, Kish International Complex Tehran, Iran. 2Professor of Architecture, University of Tehran, Iran. 3M.Sc. in architectural engineering, University of Shiraz, Shiraz, Iran. Recieved 10.06.2019; Accepted 22.10.2019 ABS TRACT: The satisfaction level with an environment differs among individuals caused by social, psychological and physical factors. One of the environmental factors affecting physical and mental satisfaction is the space thermal condition. In recent years, the importance of thermal comfort has been accentuated due to the climate change and global warming. The objective of the present s tudy is to identify the main concepts raised in Iran outdoor thermal comfort by s tudying and classifying the s tudies in this field to identify the characteris tics of each category. Thus, this s tudy reviews 142 papers written in Iran published in the period between 1999 and 2017. The papers are firs t classified into two main categories (including fundamental s tudies on thermal comfort and practical s tudies) and three secondary categories that are subsets of the second main category (macroscale, mesoscale, and microscale s tudies). Each category is then s tudied and analyzed in more details according to the regions and climates considered, methodology and research means, effective factors and thermal indices used for evaluation. -

Battling Congestion in Manila: the Edsa Problem

Transport and Communications Bulletin for Asia and the Pacific No. 82, 2013 BATTLING CONGESTION IN MANILA: THE EDSA PROBLEM Yves Boquet ABSTRACT The urban density of Manila, the capital of the Philippines, is one the highest of the world and the rate of motorization far exceeds the street capacity to handle traffic. The setting of the city between Manila Bay to the West and Laguna de Bay to the South limits the opportunities to spread traffic from the south on many axes of circulation. Built in the 1940’s, the circumferential highway EDSA, named after historian Epifanio de los Santos, seems permanently clogged by traffic, even if the newer C-5 beltway tries to provide some relief. Among the causes of EDSA perennial difficulties, one of the major factors is the concentration of major shopping malls and business districts alongside its course. A second major problem is the high number of bus terminals, particularly in the Cubao area, which provide interregional service from the capital area but add to the volume of traffic. While authorities have banned jeepneys and trisikel from using most of EDSA, this has meant that there is a concentration of these vehicles on side streets, blocking the smooth exit of cars. The current paper explores some of the policy options which may be considered to tackle congestion on EDSA . INTRODUCTION Manila1 is one of the Asian megacities suffering from the many ills of excessive street traffic. In the last three decades, these cities have experienced an extraordinary increase in the number of vehicles plying their streets, while at the same time they have sprawled into adjacent areas forming vast megalopolises, with their skyline pushed upwards with the construction of many high-rises. -

China-Iran Relations: a Limited but Enduring Strategic Partnership

June 28, 2021 China-Iran Relations: A Limited but Enduring Strategic Partnership Will Green, Former Policy Analyst, Security and Foreign Affairs Taylore Roth, Policy Analyst, Economics and Trade Acknowledgments: The authors thank John Calabrese and Jon B. Alterman for their helpful insights and reviews of early drafts. Ethan Meick, former Policy Analyst, Security and Foreign Affairs, contributed research to this report. Their assistance does not imply any endorsement of this report’s contents, and any errors should be attributed solely to the authors. Disclaimer: This paper is the product of professional research performed by staff of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission and was prepared at the request of the Commission to support its deliberations. Posting of the report to the Commission’s website is intended to promote greater public understanding of the issues addressed by the Commission in its ongoing assessment of U.S.- China economic relations and their implications for U.S. security, as mandated by Public Law 106-398 and Public Law 113-291. However, the public release of this document does not necessarily imply an endorsement by the Commission, any individual Commissioner, or the Commission’s other professional staff, of the views or conclusions expressed in this staff research report. Table of Contents Key Findings ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction......................................................................................................................................... -

12D Legend of Ancient Persia

12Days 10Nights Legend of Ancient Persia DAY 01 SINGAPORE / BANGKOK / TEHRAN (Meal on Board / Dinner) TG 402 Singapore / Bangkok 0740 / 0900 (2.5 hours) TG 527 Bangkok / Tehran 1530 / 1930 (7.5 hours) Check in at Singapore Changi International Airport (Terminal 1) for your flight to Tehran via Bangkok. Upon arrival, you will be transferred to your hotel for a good night’s rest. Overnight : 4* Ferdowsi Hotel DAY 02 TEHRAN / SHIRAZ (Breakfast / Lunch / Dinner) Your morning begins with a visit to the Golestan Palace, an immense area of 1,100,000sqm housing 18 magnificent historical palaces, 2 of which you will visit. This complex was built by the Pahlavi Dynasty and it will undoubtedly leave a lasting impression on you. Catch your domestic flight to Shiraz after lunch. On the way to your hotel, make a stop at Shah-e-Cheragh. This is one of the most beautiful shrines in Iran, the beautiful dome; wonderful lighting and impressive mirror-work will capture your attention. Overnight : 5* Chamran Grand Hotel DAY 03 SHIRAZ / PERSEPOLIS / NECROPOLIS / SHIRAZ (Breakfast / Lunch / Dinner) After breakfast, full day excursion of Persepolis and Necropolis awaits you. Persepolis was founded by Darius I in 518BC, as the capital of the Achaemenid Empire. It was built on an immense half artificial, half natural terrace, where this king of kings at that time created an impressive palace complex inspired by Mesopotamian models. The historical importance and quality of the monumental ruins make it a unique archaeological site. It seems that Darius planned this impressive complex of palaces not only as the seat of government but also, and primarily, as a show place and a spectacular centre for the receptions and festivals of the Achaemenid kings and their empire, such as for the celebration of Nawruz. -

Page 01 Tehran' 01925 191608Z 47' S Action, Nea 15' Info : Oct

PAGE 01 TEHRAN' 01925 191608Z 47' S ACTION, NEA 15' INFO : OCT 01PEUR! 17 n EA 10,CIAE, 001DODE, 00,JPM , 04,H 02'.* 1NR: 07,,L. 03a NsAE, emprsisc , 10PP e4,Rsc: obs p ! 02. SS vaiLysiA 12d0 13 ... EL isiNic 1 ACDA 16,Am 28/1 GA, 02, COM , •08, DOT 1 . RSR . :)61, /204 W' 044183' R! 1914102 MAY 69 FM! AMEMBASSY TEHRAN' TO' SECSTATE: WASHDC` 8360 INFO' AMEMBASSY . ANKARA AMEMBASSY BANGKOK! AMEMBASSY JIDDA AMEMBASSY KUWAIT . AMEMBASSY LONDON AMEMBASSY MOSCOW AMEMBASSY RAWALPINDI USMISSION USUN , — 0,T TEHRAN 1925,.-:—'''-- c),.:.,' i0101000 ,:n _ - , SUBJi IRAW.IRAO DISPUTE OVER SHATTi, f". REFS.! A- . 17‘ TEHRAN 1170s 1399' NOT ALi BANGKOK FOR SOBER SUMMARY! IRAN-IRAQ' CRISIS OVER SHATT WAS FORCED BY GOI, PROBABLY TO STRENGTHEN IRANIAN LEADERSHIP' IN GULFo RISKS' OF CONFLICT WERE KEPT 1,0W0 TENSION HAS ABATED : * NEGOTIATIONS : UNLIKELY' SOON BUT IRAN HAS ESTABLISHED: NEW RIVER REGIME' FOR IRANIAN' SHIPS WHOLLY OWNED AND CHARTERED'. IRANIAN DETERMINATION TO PRESS FOR. "RIGHTS" IN GULF PROBABLY STRONGER. 10 TENSION BETWEEN IRAN AND IRAQ OVER SHATT-AL ,=ARAB HAS EASED WITH HIGW-LEVEL: IRANIAN OFFICIALS CLAIMING "OBJECTIVES" REACHED. ELEMENTS OF DISCORD REMAIN (TROOPS OF- BOTH. SIDES STILL DEPLOYED :. IRAN /MPOSSIBLY STILL STUDYING WAYS TO AFFECT RIVER REGIME FOR THIRD - \COUNTRY SHIPPING, IRAQ STILL MISTREATING AND EXPELLING• IRANIANS AND APPARENTLY ENERGIZING KHUZISTAN LIBERATION FRONT) BUT BOTH 2 .. , . , .. _ PAGE 02 TEHRAN' 01925 191608Z SIDES SEEM FOR MOMENT AT LEAST NOT TD WISH; To HEAT SITUATION UP AGAINo EMB OFFERS FOLLOWING COMMENTS ON THIS. “cRISIS09Q 24 ALTHOUGH IRAQI GOVT - IN THIS AS IN OTHER MATTERS HAS BEEN-UND/P'. -

Board of Governors on the Developments

IAEA INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY (IAEA) Board of Governors General Cornel Feruta acting Director General of In accordance with the statute and the existing the International Atomic Energy Agency. practice, the Board is responsible for approving safeguards procedures and safeguards 2018: The Chair of the Board of Governors for agreements, and for the general supervision of 2017-2018 was Ambassador Darmansjah the Agency’s safeguards activities. The board Djumala of Indonesia. generally meets five times a year: March, June, before and after the regular session of the On March 5-9, the Board of Governors convened General Conference in September, and in Vienna, Austria. Director Amano stated that immediately after the meeting of its Technical Iran is meeting its nuclear-related commitments Assistance and Cooperation Committee in and the IAEA has access to all necessary sites. December. At its meetings, the board also examines and makes recommendations to the The Board will also consider the 2018 IAEA General Conference on the IAEA's accounts, Nuclear Safety Review and the 2018 Nuclear Technology Review. program, and budget and considers applications for membership. From 4-8 June, the Board of Governors met in The Board of Governors has 35 members, of Vienna for its second meeting of the year. which 13 are designated by the board and 22 are Director Amano addressed the Board on the elected by the General Conference. subject of North Korea, inspections of Iranian The elected Member States on the board for facilities under the Additional Protocol and JCPOA, and highlighted sustainable 2017-2018 are: Algeria, Argentina, Armenia, development projects undertaken by the IAEA. -

NPR 16.1: Jean Du Preez Interviews Ambassador Yukiya Amano on The

INTERVIEW MAKING THE AGENDA STICK Lessons Learned From the 2007 NPT PrepCom Jean du Preez interviews Ambassador Yukiya Amano After the conclusion of the 2008 Preparatory Committee (PrepCom) for the 2010 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), the Nonproliferation Review interviewed Ambassador Yukiya Amano of Japan, who presided over the 2007 session of the PrepCom in Vienna. He provided valuable insights into his preparations for the PrepCom and shared his thoughts on some of the most pressing issues that confronted his chairmanship and the PrepCom as a whole. The interview also provides useful perspectives on the future of the strengthened review process. KEYWORDS: Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons; nuclear nonproliferation; nuclear disarmament The legacy of the 2007 Preparatory Committee (PrepCom) for the 2010 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) is one of deep disputes among delegations on how to reflect the significance of past agreements and the implementation of the treaty. Despite vigorous efforts by PrepCom Chairman Yukiya Amano to consult widely with delegations prior to the start of the meeting, these differences prolonged the adoption of the agenda until the second week. This in turn limited substantive discussion of some of the treaty’s most significant challenges. Ambassador Amano is the permanent representative of Japan to international organizations in Vienna and has served as Japan’s governor on the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Board of Governors since September 2005. He has held increasingly senior positions in the Japanese Foreign Ministry, notably as director- general of the Disarmament, Nonproliferation, and Science Department. -

Agroclimatic Zones Map of Iran Explanatory Notes

AGROCLIMATIC ZONES MAP OF IRAN EXPLANATORY NOTES E. De Pauw1, A. Ghaffari2, V. Ghasemi3 1 Agroclimatologist/ Research Project Manager, International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), Aleppo Syria 2 Director-General, Drylands Agricultural Research Institute (DARI), Maragheh, Iran 3 Head of GIS/RS Department, Soil and Water Research Institute (SWRI), Tehran, Iran INTRODUCTION The agroclimatic zones map of Iran has been produced to as one of the outputs of the joint DARI-ICARDA project “Agroecological Zoning of Iran”. The objective of this project is to develop an agroecological zones framework for targeting germplasm to specific environments, formulating land use and land management recommendations, and assisting development planning. In view of the very diverse climates in this part of Iran, an agroclimatic zones map is of vital importance to achieve this objective. METHODOLOGY Spatial interpolation A database was established of point climatic data covering monthly averages of precipitation and temperature for the main stations in Iran, covering the period 1973-1998 (Appendix 1, Tables 2-3). These quality-controlled data were obtained from the Organization of Meteorology, based in Tehran. From Iran 126 stations were accepted with a precipitation record length of at least 20 years, and 590 stations with a temperature record length of at least 5 years. The database also included some precipitation and temperature data from neighboring countries, leading to a total database of 244 precipitation stations and 627 temperature stations. The ‘thin-plate smoothing spline’ method of Hutchinson (1995), as implemented in the ANUSPLIN software (Hutchinson, 2000), was used to convert this point database into ‘climate surfaces’.