Download This

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Signers of the United States Declaration of Independence Table of Contents

SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE 56 Men Who Risked It All Life, Family, Fortune, Health, Future Compiled by Bob Hampton First Edition - 2014 1 SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTON Page Table of Contents………………………………………………………………...………………2 Overview………………………………………………………………………………...………..5 Painting by John Trumbull……………………………………………………………………...7 Summary of Aftermath……………………………………………….………………...……….8 Independence Day Quiz…………………………………………………….……...………...…11 NEW HAMPSHIRE Josiah Bartlett………………………………………………………………………………..…12 William Whipple..........................................................................................................................15 Matthew Thornton……………………………………………………………………...…........18 MASSACHUSETTS Samuel Adams………………………………………………………………………………..…21 John Adams………………………………………………………………………………..……25 John Hancock………………………………………………………………………………..….29 Robert Treat Paine………………………………………………………………………….….32 Elbridge Gerry……………………………………………………………………....…….……35 RHODE ISLAND Stephen Hopkins………………………………………………………………………….…….38 William Ellery……………………………………………………………………………….….41 CONNECTICUT Roger Sherman…………………………………………………………………………..……...45 Samuel Huntington…………………………………………………………………….……….48 William Williams……………………………………………………………………………….51 Oliver Wolcott…………………………………………………………………………….…….54 NEW YORK William Floyd………………………………………………………………………….………..57 Philip Livingston…………………………………………………………………………….….60 Francis Lewis…………………………………………………………………………....…..…..64 Lewis Morris………………………………………………………………………………….…67 -

City of Somerville, Massachusetts Mayor’S Office of Strategic Planning & Community Development Joseph A

CITY OF SOMERVILLE, MASSACHUSETTS MAYOR’S OFFICE OF STRATEGIC PLANNING & COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT JOSEPH A. CURTATONE MAYOR MICHAEL F. GLAVIN EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR HISTORIC PRESERVATION COMMISSION DETERMINATION OF SIGNIFICANCE STAFF REPORT Site: 151 Linwood Street Case: HPC 2018.100 Applicant Name: AREC 8, LLC Date of Application: September 6, 2018 Recommendation: NOT Significant Hearing Date: October 16, 2018 I. Historical Association Historical Context: “The trucking industry in the United States has affected the political and economic history of the United States in the 20th century. Before the invention of automobiles, most freight was moved by train or horse-drawn vehicle. “During World War I, the military was the first to use trucks extensively. With the increased construction of paved roads, trucking began to achieve significant foothold in the 1930s, and soon became subject to various government regulations (such as the hours of service). During the late 1950s and 1960s, trucking was accelerated by the construction of the Interstate Highway System, an extensive network of freeways linking major cities across the continent.”1 1 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_trucking_industry_in_the_United_States accessed 10/5/2018 CITY HALL ● 93 HIGHLAND AVENUE ● SOMERVILLE, MASSACHUSETTS 02143 (617) 625-6600 EXT. 2500 ● TTY: (617) 666-0001 ● FAX: (617) 625-0722 www.somervillema.gov Page 2 of 15 Date: October 16, 2018 Case: HPC 2018.100 Site: 151 Linwood Street Evolution of Site: taken from the NR Nomination Form for 1 Fitchburg Street Development of the Brick Bottom Neighborhood “(T)he streets of the adjacent Brick Bottom neighborhood were determined at a much earlier date. In June of 1857, the Boston & Lowell Railroad hired William Edson, "delineator" of the J.H. -

The Legacy of Alida Livingston of New York

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2011 A Dutch Woman in an English World: The Legacy of Alida Livingston of New York Melinda M. Mohler West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Mohler, Melinda M., "A Dutch Woman in an English World: The Legacy of Alida Livingston of New York" (2011). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 4755. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/4755 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Dutch Woman in an English World: The Legacy of Alida Livingston of New York Melinda M. Mohler Dissertation submitted to the College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Jack Hammersmith, Ph.D., Chair Mary Lou Lustig, Ph.D. Elizabeth Fones-Wolf, Ph.D. Kenneth Fones-World, Ph.D. Martha Pallante, Ph.D. -

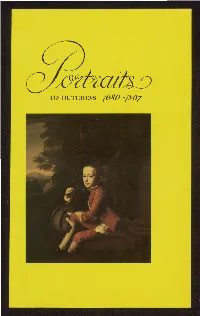

Portraits of Dutchess

OF DUTCHESS /680 ,.,/807 Cover: DANIEL CROMMELIN VERPLANCK 1762-1834 Painted by John Singlecon Copley in 1771 CottrteJy of The Metropolitan J\f11Jeum of Art New York. Gift of Bayard Verplanck, 1949 (See page 42) OF DUTCHESS /680-/807 by S. Velma Pugsley Spo11sored by THE DUTCHESS COUNTY AMERICAN REVOLUTION BICENTENNIAL COMMISSION as a 1976 Project Printed by HAMILTON REPRODUCTIONS, Inc. Poughkeepsie, N. Y. FOREWORD The Bicentennial Project rirled "Portraits of Dutchess 1680-1807" began as a simple, personal arrempr ro catalog existing porrrairs of people whose lives were part of rhe county's history in rhe Colonial Period. As rhe work progressed ir became certain rhar relatively few were srill in the Durchess-Purnam area. As so many of rhem had become the property of Museums in other localities it seemed more important than ever ro lisr rhem and their present locations. When rhe Dutchess County American Revolution Bicentennial Commission with great generosity undertook rhe funding ir was possible ro illustrate rhe booklet with photographs from rhe many available sources. This document is nor ro be considered as a geneological or historic record even though much research in rhose directions became a necessity. The collection is meant ro be a pictorial record, only, hoping rhar irs readers may be made more aware rhar these paintings are indeed pictures of our ancestors. Ir is also hoped rhar all museum collections of Colonial Painting will be viewed wirh deeper and more personal interest. The portraits which are privately owned are used here by rhe gracious consent of the owners. Those works from public sources are so indicated. -

COURIER the National Park Service Newsletter Vol

COURIER The National Park Service Newsletter Vol. 3, No. 7 Washington, D.C. June 1980 Governors speak out on the parks By Candace Garry Governor Bruce Babbitt of Arizona, However, the relationship between State Public Information Specialist, WASO like other State chief executives spends a and Federal officials concerning land lot of time in national parks. His zest for acquisition and Government regulations (Editor's Note: This article includes excerpts the Park Service and about resource has been delicate in some areas. from brief interviews conducted by Candace management and conservation began Nevertheless, State officials and the Park Garry with Governors from nine states, during with his love for the Grand Canyon in Service generally have worked in the 1980 Winter meeting of the National Arizona. He teases, "Why, the Grand harmony. Governors' Association in Washington, D.C. Canyon is the head of the American flag Ed Herschler is Garry, a Public Information Specialist in the where I come from!" Such pride in their Governor of Wyo Washington Office, talked to Governors individual State's natural, cultural, and ming, a State Lamm of Colorado, Babbitt of Arizona, Herschler of Wyoming, Matheson of Utah, historical areas preserved for public that boasts two of the King of New Mexico, King of Massachusetts, enjoyment by the National Park Service is largest and most Hughes of Maryland, Thornburgh of common among State officials. well-known areas Pennsylvania, and Graham of Florida about Governor Babbitt's pride runs in the entire Park their experiences with the National Park especially deep, as does his knowledge System, Grand Service.) and understanding of the Grand Canyon. -

The Colonial Family: Kinship Nd Power Peter R

The Colonial Family: Kinship nd Power Peter R. Christop New York State Library ruce C. Daniels in a 1985 book review wrote: “Each There is a good deal of evidence in the literature, year since the late 1960sone or two New England town therefore, that in fact the New England town model may studies by professional historians have been published; not at all be the ideal form to use in studying colonial lheir collective impact has exponentially increased our New York social structure. The real basis of society was knowledge of the day-to-day life of early America.“’ not the community at all, but the family. The late Alice One wonders why, if this is so useful an historical P. Kenney made the first step in the right direction with approach, we do not have similar town studies for New her study of the Gansevoort family.6 It is indeed the York. It is not for lack of recordsthat no attempt hasbeen family in colonial New York that historians should be made. Nor can one credit the idea that modern profes- studying, yet few historians have followed Kenney’s sional historians, armed with computers, should feel in lead. A recent exception of note is Clare Brandt’s study any way incapable of dealing with the complexity of a of the Livingston family through several generations.7 multinational, multiracial, multireligious community. However, we should note that Kenney and Brandt have restricted their attention to persons with one particular One very considerable problem for studying the surname, ignoring cousins, grandparents, and colonial period was the mobilily Qf New Yorkers, grandchildren with other family namesbut nonetheless especially the landed and merchant class. -

H EL E N H a Y

H E L E N H A y E s Gardener, Actress "All through the long winter I dream of my garden. On the first warm day of Spring I dig my fingers deep into the soft earth. I can feel its energy, and my spirits soar. My Miracle-Gro has been a trusted friend for more than 30 years. It does such wonderful things for everything that grows." for ALL FLOWERS ALL VEGETABLES ALL GARDEN PLANTS MIRACLE-GRO eric an Horticulturist Volume 71, N umber 4 April 1992 ARTICLES It All Started With Mr. Conover by John A. Lynch . .... .. .... .. ... .. ... ... ... ... 14 A gift to a curious neighbor boy launched a life-long love of woodland plants. Increasing Our Native Intelligence by Erin Hynes . .. .... .. .. .. ... ..... .... .. ....... 21 Understanding how plants compete and cooperate is a focus of research at the Austin-based National Wildflower Research Center. The Tree Peony: King of Flowers by Patricia Kite . ....... ... .. ... .. .. .. .... ... 24 After fourteen centuries of cultivation, the best ones are still as rare as the proverbial day in May. APRIL'S COVER Wiggly Creatures and Amazing Mazes Ph otographed by John A. Lynch by Brian Holley .. ........ .. .. ... ... .... .. ..... ... 30 The supervisor of the Teaching Garden at the Royal Botanical Gardens John Lynch grows pink turtlehead, Chelone lyonii, in a moist spot at the in Ontario has learned a thing or two from his students. lowest point in his wildflower garden. Native to the mountains of A Tree History: The American Yellowwood the southeastern United States, it is by Susan Sand . ...... .. ......... .. .. .. .. .. ..... .. 35 one of the best Chelone species for Gray bark, pealike flowers, and yellow fall foliage are among the garden. -

Comprehensive Plan

Town of Rockland Sullivan County, NY COMPREHENSIVE PLAN September 2010 Prepared by: Town of Rockland Comprehensive Plan Committee Town of Rockland Town Board DRAFT FOR REVIEW & DISCUSSION Town of Rockland, Sullivan County, New York Comprehensive Plan - 2010 Foreword This plan was prepared by the Town of Rockland Comprehensive Plan Committee with support from the Town of Rockland Town Board and Planning Board. Town of Rockland Comprehensive Plan Committee Patricia Pomeroy, Chair Dr. Alan Fried Sheila Shultz Harvey Susswein Kenneth Stewart Fred Emery Patricia Adams Tom Ellison Town of Rockland Town Board Ed Weitmann, Supervisor Glen Carlson Rob Eggleton William Roser, Jr. Eileen Mershon Town of Rockland Planning Board Tom Ellison, Chair Phil Vallone Richard Barnhart James Severing Carol Park Chris Andreola Nancy Hobbs Consultant - Shepstone Management Company We also acknowledge the help of the following: Theodore Hartling, Highway Superintendent; Robert Wolcott, Water and Sewer Superintendent; Cynthia Theadore, Assessor; Charles Irace, Code Enforcement Officer; in addition to Tasse Niforatos, Bill Browne and Rebecca Ackerly. Special recognition is given to Stanley Martin, and the late Patrick Casey, former Town Supervisors, for their support and dedication to the future needs of the Town of Rockland. September 2010 Foreword i Town of Rockland, Sullivan County, New York Comprehensive Plan - 2010 Table of Contents Foreword i Table of Contents ii 1.0 Introduction 1-1 2.0 Background Studies 2-1 2.1 Regional Location and History 2-1 2.2 Natural -

Livingston Family Papers

A Guide to the Livingston Family Papers Collection Summary Collection Title: The Livingston Family Papers Call Number: MG 115 Creator: Unknown Inclusive Dates: 1853-1920’s Bulk Dates: 1880’s Abstract: The collection consists primarily of family photographs and notes on Livingston genealogy. Quantity: 1 document box; 5 linear inches. Administrative Information Custodial History: The collection was gifted to the Albany Institute by Mr. and Mrs. Roland P. Carreker in October, 1986. Preferred Citation: The Livingston Family Papers, MG 115. Albany Institute of History & Art Library, New York. Acquisition Information: Accession #: 2001.150 Accession Date: 12 April 2001 Processing Information: Processed by Rachel Dworkin; completed on January 28, 2005. Restrictions Restrictions on Access: None. Restrictions on Use: Permission to publish material must be obtained in writing prior to publication from the Chief Librarian & Archivist, Albany Institute of History & Art, 125 Washington Avenue, Albany, NY 12210. Index Term Persons: Places: Herrick, Livingston Morse Albany, NY Livingston, Henry Gilbert, Rev. Ridgefield, NY Livingston, Julia Raymond Livingston, Robert Material Types: Morse, Gilbert Livingston Notebook Morse, May Photographs Morse, Percy Livingston Passports Morse, Sidney Edwards Painting - watercolor Schuyler, Montgomery Wheeler, Anne Lorraine Subjects: Genealogy -- Livingston family Genealogy -- Burrill family Genealogy -- Dudley family Genealogy -- Farrington family Genealogy -- Kane family Genealogy -- Ruckman family Genealogy -- Russell family Genealogy -- Moss family New York (State) -- History History of the Livingstons Reverend Gilbert Henry Livingston (February 3,1821- January 27,1855) was the son of Reverend Gilbert R. Livingston and Eliza Burrill Livingston. He was a direct descendant of Robert Livingston, the first Lord of Livingston Manor. On June 8, 1847 he married Sarah Raymond. -

![[Title, Inclusive Dates]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6406/title-inclusive-dates-3916406.webp)

[Title, Inclusive Dates]

Livingston family papers, 1719-1929, bulk dates 1736-1810 3 boxes (1.3 linear feet) Museum of the City of New York 1220 Fifth Avenue New York, NY 10029 Telephone: 212-534-1672 Fax: 212-423-0758 [email protected] www.mcny.org © Museum of the City of New York. All rights reserved. Prepared by Jeremy Zoref, archival intern, under the supervision of Lindsay Turley, Manuscripts and Reference Archivist December 2012 Description is in English Descriptive Summary Creator: Livingston family members and descendants. Title: Livingston family papers Dates: 1719-1929, bulk dates 1736-1810 Abstract: A combination of seven gifts from Livingston family descendents, the collection contains correspondences to and from various Livingston family members, and is strong in national politics of the Revolutionary Era/Early Republic. Extent: 3 boxes (1.3 linear feet) MCNY numbers: PRO2012.11; accessions 44.144.14-16, 44, 97-98, 100-101; 47.173.1-280, 282- 314, 316-320, 322-326; 97.41.262-271; 57.96.3-4; 56.70 Language: English Biographical Note The Livingston family was one of the most powerful families in both Colonial New York, and New York State during the early republic through the end of the market revolution. Though their power and influence declined in the second half of the nineteenth-century, the Livingston family remained within the circle of New York’s elite through both wealth as well as a modicum of social capital based on extensive family connections. Robert Livingston (1654-1728) was the first to come to British North America. When he was a boy, his family fled to Holland after his father had been exiled from Scotland for trying to Anglicize the Presbyterian Church. -

Two Gardens and a View: Revealing the History and the Future of an American Country Place in Western New York — Linwood

Two Gardens and a View: Revealing the History and the Future of An American Country Place in Western New York — Linwood by Karen E. Cowperthwaite Major Professor: George W. Curry Committee: John Auwaerter Project Report Submitted in Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Landscape Architecture Degree LSA 800 Capstone Studio Department of Landscape Architecture State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry Syracuse, New York April 30, 2008 Approved by: Major Professor: George W. Curry _________________________________ Date: _________ Committee: John Auwaerter ______________________________________Date: _________ Chair, Department of Landscape Architecture Richard S. Hawks_________________________________________________ Date: __________ i Acknowledgements______________________________________________ I am fortunate to have had such a great project and team. Thank you to George W. Curry for introducing Linwood to me and for your encouragement and wisdom over the past three years. To John Auwaerter, I am grateful for your infinite patience and careful attention to all the projects we’ve worked on together. Thank you to Christine Capella-Peters for your support and enthusiasm for Linwood and this project. Kathy Stribley, thank you for helping me with programming and matrices. Special appreciation goes to Lee Gratwick, her daughter Clara Gratwick Mulligan and her niece Becky Lewis, for being so welcoming and who shared time, stories, and family albums with such generosity. Dick Heye, fellow Linwood history buff, thank you for sharing your discoveries. To Robert Cuchetto and all my friends, thank you for waiting. ii Table of Contents________________________________________________ Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………………………ii Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………………….iii List of Figures………………………………………………………………………………..iv Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………....vi I. Introduction A. Why Linwood?...........................................................................................................1 B. -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property_____________ historic name Hudson River Historic District_______________________________________ other names/site number 2. Location street & number east side Hudson River between Germantown & Staatsburg | I not for publication city, town Tivoli, Annandale, Barrytown, Rhineclif f, Staatsburg I X | vicinity state New York code 36 county Dutchess,Columbiacode 027,021 zip code 12583,12504, 12507,12534,12580 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property [x] private I I building(s) Contributing Noncontributing fxl public-local H district 1376 659 buildings fxl public-State I I site sites |x| public-Federal I I structure structures I I object objects ____ ____ Total Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously n/a -JD-L 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this I I nomination I I request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60.